Living with Long COVID in a Southern State: A Comparison of Black and White Residents of North Carolina

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Eligibility

2.2. Measures

- (1)

- How many times have you had a COVID-19 infection, even if you were not tested?Never (not that I know of); 1 time; 2 times; 3 times or more; Prefer not to answer

- (2)

- How long did your symptoms last after you first knew you had COVID-19? (If you had COVID more than once, pick the longest time your symptoms lasted).Less than a week; 1 to 2 weeks; 2 weeks to about a month; Between 1 to 3 months; Longer than 3 months

- (3)

- Did you get new symptoms after recovering from your COVID infection(s)?Yes; No; Don’t know/not sure

- (4)

- The disease known as Long COVID means having COVID symptoms that lasted for more than a month or 30 days OR getting new symptoms after the infection is over. Do you think that you have or had Long COVID?Yes; No; Don’t know/not sure; Prefer not to answer

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Total Study Population

3.2. Participants with Long COVID or COVID-19 Only

3.3. Characteristics Among White and Black Participants with Long COVID or COVID-19 Only

3.4. Feelings and Activities Among Black and White Participants with Long COVID Only

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ely, E.W.; Brown, L.M.; Fineberg, H.V. Long Covid Defined. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjaye-Gbewonyo, D.; Vahratian, A.; Perrine, C.G.; Bertolli, J. Long COVID in Adults: United States, 2022; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Ahrnsbrak, R.; Rekito, A. Evidence Mounts That About 7% of US Adults Have Had Long COVID. JAMA 2024, 332, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics. U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief: Long COVID Household Pulse Survey. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/long-covid.htm (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Padilla, S.; Ledesma, C.; García-Abellán, J.; García, J.A.; Fernández-González, M.; de la Rica, A.; Galiana, A.; Gutiérrez, F.; Masiá, M. Long COVID across SARS-CoV-2 Variants, Lineages, and Sublineages. iScience 2024, 27, 109536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakefield, W.S.; Olusanya, O.A.; White, B.; Shaban-Nejad, A. Social Determinants and Indicators of COVID-19 Among Marginalized Communities: A Scientific Review and Call to Action for Pandemic Response and Recovery. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalsania, A.K.; Fastiggi, M.J.; Kahlam, A.; Shah, R.; Patel, K.; Shiau, S.; Rokicki, S.; DallaPiazza, M. The Relationship Between Social Determinants of Health and Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Mortality. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.A.; Whitaker, M.; Anglin, O.; Milucky, J.; Patel, K.; Pham, H.; Chai, S.J.; Alden, N.B.; Yousey-Hindes, K.; Anderson, E.J.; et al. COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations Among Adults During SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron Variant Predominance, by Race/Ethnicity and Vaccination Status—COVID-NET, 14 States, July 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Berger, N.A.; Kaelber, D.C.; Davis, P.B.; Volkow, N.D.; Xu, R. COVID Infection Rates, Clinical Outcomes, and Racial/Ethnic and Gender Disparities before and after Omicron Emerged in the US 2022. MedRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khullar, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, F.; Weiner, M.G.; Carton, T.W.; Rothman, R.L.; Block, J.P.; Kaushal, R. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in New York: An EHR-Based Cohort Study from the RECOVER Program. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartsch, S.M.; Chin, K.L.; Strych, U.; John, D.C.; Shah, T.D.; Bottazzi, M.E.; O’Shea, K.J.; Robertson, M.; Weatherwax, C.; Heneghan, J.; et al. The Current and Future Burden of Long COVID in the United States (U.S.). J. Infect. Dis. 2025, jiaf030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, K. New Data Shows Long Covid Is Keeping as Many as 4 Million People Out of Work; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/new-data-shows-long-covid-is-keeping-as-many-as-4-million-people-out-of-work/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Karpman, M.; Foil, O.; Popkin, S.J.; McCorkell, L.; Waxman, E.; Morriss, S. Employment and Material Hardship Among Adults with Long COVID in December 2022; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/Employment%20and%20Material%20Hardship%20among%20Adults%20with%20Long%20COVID%20in%20December%202022.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Packard, S.E.; Susser, E. Association of Long COVID with Housing Insecurity in the United States, 2022–2023. SSM Popul. Health 2023, 25, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaei, A.; Zhang, R.; Taylor, S.; Tam, C.-C.; Yang, C.-H.; Li, X.; Qiao, S. Impact of COVID-19 Symptoms on Social Aspects of Life among Female Long Haulers: A Qualitative Study. Research Square 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutterbuck, D.; Ramasawmy, M.; Pantelic, M.; Hayer, J.; Begum, F.; Faghy, M.; Nasir, N.; Causer, B.; Heightman, M.; Allsopp, G.; et al. Barriers to Healthcare Access and Experiences of Stigma: Findings from a Coproduced Long Covid Case-finding Study. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.H.; Womack, K.N.; Tenforde, M.W.; Files, D.C.; Gibbs, K.W.; Shapiro, N.I.; Prekker, M.E.; Erickson, H.L.; Steingrub, J.S.; Qadir, N.; et al. Associations between Persistent Symptoms after Mild COVID-19 and Long-Term Health Status, Quality of Life, and Psychological Distress. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2022, 16, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmans, R.S.; Chambers-Peeple, K.; Yu, C.; Xiao, L.Z.; Wegryn-Jones, R.; Martin, A.; Dell’Imperio, S.; Aboul-Hassan, D.; Williams, D.A.; Clauw, D.J.; et al. ‘I’m Still Here, I’m Alive and Breathing’: The Experience of Black Americans with Long COVID. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwill, J.R.; Ajibewa, T.A. A Mixed Methods Analysis of Long COVID Symptoms in Black Americans: Examining Physical and Mental Health Outcomes. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague Martinez, L.; Sharma, N.; John, J.; Battaglia, T.A.; Linas, B.P.; Clark, C.R.; Hudson, L.B.; Lobb, R.; Betz, G.; Ojala O’Neill, S.O.; et al. Long COVID Impacts: The Voices and Views of Diverse Black and Latinx Residents in Massachusetts. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garra, G.; Singer, A.J.; Taira, B.R.; Chohan, J.; Cardoz, H.; Chisena, E.; Thode, H.C., Jr. Validation of the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale in Pediatric Emergency Department Patients. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2010, 17, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, I.A.; Pilkington, W.; Brown, L.; Billings, V.; Hoffler, U.; Paulin, L.; Kimbro, K.S.; Baker, B.; Zhang, T.; Locklear, T.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Underserved Communities of North Carolina. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Long COVID | COVID-19 Only | NO COVID-19 | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Column% | N | Column% | N | Column% | N | ||

| Total | 133 | (51.5) | 83 | (32.2) | 42 | (16.3) | 258 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Asian | 3 | (2.3) | 2 | (2.4) | 2 | (4.8) | 7 | (2.7) |

| American Indian | 3 | (2.3) | 7 | (8.4) | 3 | (7.1) | 13 | (5.0) |

| Black | 73 | (54.9) | 54 | (65.1) | 32 | (76.2) | 159 | (61.6) |

| Latino | 5 | (3.8) | 0 | 0 | 5 | (1.9) | ||

| White | 41 | (30.8) | 16 | (19.3) | 2 | (4.8) | 59 | (22.9) |

| Other race | 1 | (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 | (0.4) | ||

| Multirace | 6 | (4.5) | 2 | (2.4) | 0 | 8 | (3.1) | |

| Declined to report | 1 | (0.8) | 2 | (2.4) | 3 | (7.1) | 6 | (2.3) |

| Age | 42.7 | 42.1 | 46.5 | 43.1 | ||||

| (95% CI) | (40.3 45.0) | (38.7 45.5) | (41.5 51.5) | (41.3 45.0) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Woman | 101 | (76.5) | 57 | (68.7) | 21 | (50.0) | 179 | (69.6) |

| Man | 28 | (21.2) | 26 | (31.3) | 20 | (47.6) | 74 | (28.8) |

| Other | 3 | (2.3) | 0 | 1 | (2.4) | 4 | (1.6) | |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/cohabitating | 55 | (42.0) | 26 | (31.3) | 12 | (30.0) | 93 | (36.6) |

| Separated/divorced/widow | 19 | (14.5) | 13 | (15.7) | 8 | (20.0) | 40 | (15.7) |

| Single | 57 | (43.5) | 44 | (53.0) | 20 | (50.0) | 121 | (47.6) |

| Education | ||||||||

| ≤High school/GED | 35 | (27.0) | 28 | (35.0) | 23 | (57.5) | 86 | (34.4) |

| Trade/some college | 38 | (29.2) | 24 | (30.0) | 10 | (25.0) | 72 | (28.8) |

| Bachelor degree | 33 | (25.4) | 20 | (25.0) | 4 | (10.0) | 57 | (22.8) |

| Graduate degree | 24 | (18.5) | 8 | (10.0) | 3 | (7.5) | 35 | (14.0) |

| Annual income | ||||||||

| <USD 40 k | 58 | (43.6) | 38 | (45.8) | 24 | (57.1) | 120 | (46.5) |

| USD 40–79 k | 37 | (27.8) | 21 | (25.3) | 9 | (21.4) | 67 | (26.0) |

| >USD 80 k | 28 | (21.1) | 13 | (15.7) | 4 | (9.5) | 45 | (17.4) |

| Not reported | 10 | (7.5) | 11 | (13.3) | 5 | (11.9) | 26 | (10.1) |

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Employed | 81 | (60.9) | 57 | (68.7) | 21 | (50.) | 159 | (61.6) |

| Unemployed | 24 | (18.0) | 5 | (6.0) | 9 | (21.4) | 38 | (14.7) |

| Not in work force | 28 | (21.1) | 21 | (25.3) | 12 | (28.6) | 61 | (23.6) |

| Changes in work status since pandemic or long COVID-19 (not mutually exclusive) | ||||||||

| Less time/changed tasks | 48 | (36.1) | 17 | (23.6) | 7 | (9.7) | 72 | (8.0) |

| Stopped working | 33 | (25.8) | 8 | (9.6) | 2 | (4.7) | 43 | (17.0) |

| White | Black | Total | Chi-sq or | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (Col %) | N | (Col %) | N | (Col %) | Fischer’s Exact | |

| Total | 60 | (31.4) | 131 | (68.6) | 191 | p-Value | |

| Long COVID | |||||||

| Yes | 44 | (73.3) | 75 | (57.3) | 119 | (62.3) | 0.033 |

| No | 16 | (26.7) | 56 | (42.7) | 72 | (37.7) | |

| Recovered from LC (only LC participants) | |||||||

| Yes | 8 | (18.2) | 32 | (43.2) | 40 | (33.9) | 0.004 |

| No | 26 | (59.1) | 22 | (29.7) | 48 | (40.7) | |

| Don’t know | 10 | (22.7) | 20 | (27.0) | 30 | (25.4) | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Woman | 45 | (77.6) | 94 | (71.8) | 139 | (73.5) | 0.402 |

| Man | 13 | (22.4) | 37 | (28.2) | 50 | (26.5) | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married/cohabitating | 29 | (48.3) | 46 | (35.4) | 75 | (39.5) | 0.003 |

| Separated/divorced/widow | 15 | (25.0) | 16 | (12.3) | 31 | (16.3) | |

| Single | 16 | (26.7) | 68 | (52.3) | 84 | (44.2) | |

| Education | |||||||

| ≤High school/GED | 8 | (13.3) | 49 | (39.9) | 57 | (30.6) | 0.005 |

| Trade/some college | 20 | (33.3) | 34 | (27.0) | 54 | (29.0) | |

| Bachelor degree | 18 | (30.0) | 29 | (23.0) | 47 | (25.3) | |

| Graduate degree | 14 | (23.3) | 14 | (11.1) | 28 | (15.1) | |

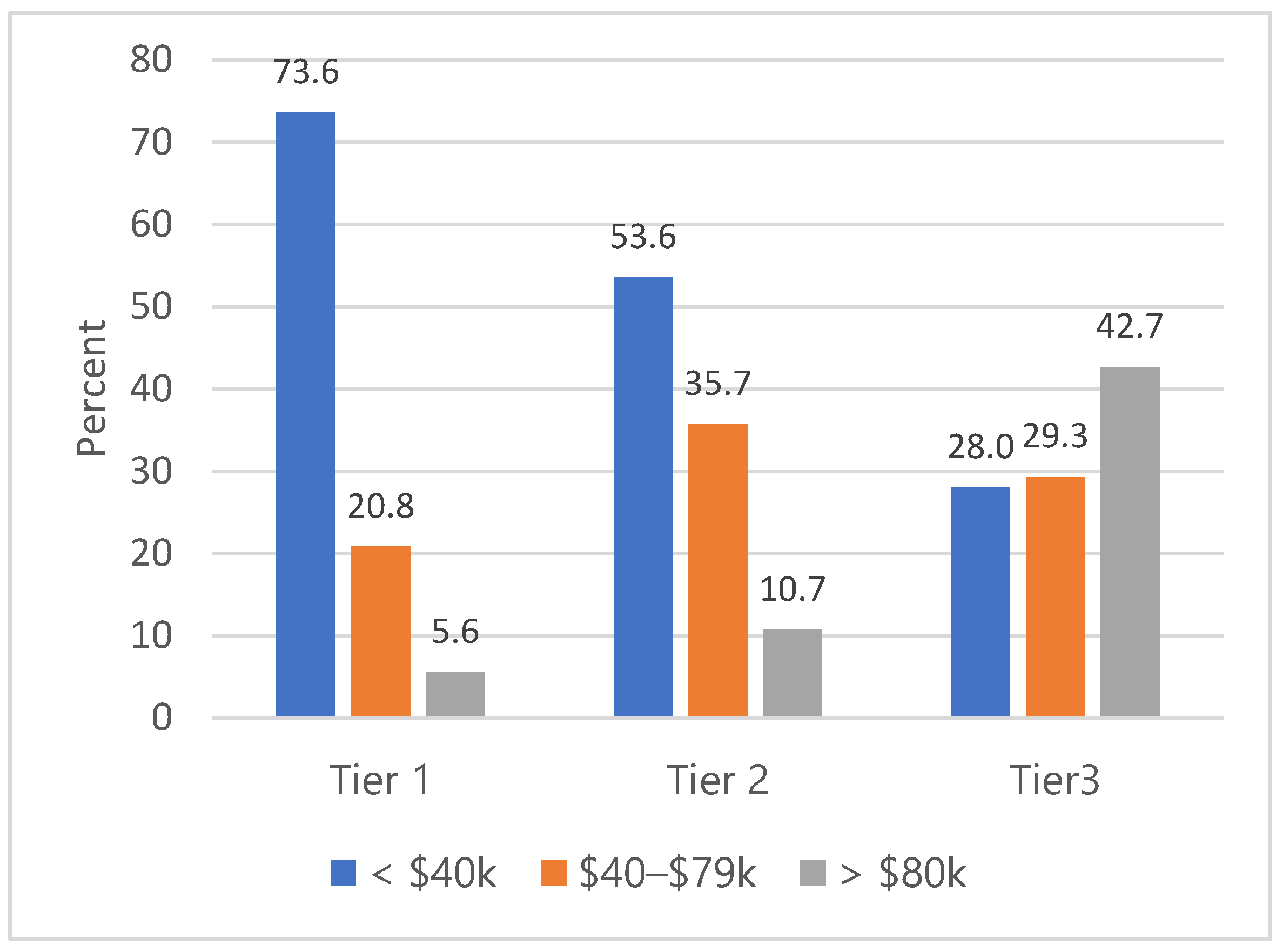

| Annual income | |||||||

| <USD 40 k | 16 | (26.7) | 63 | (48.1) | 79 | (41.4) | 0.010 |

| USD 40–79 k | 19 | (31.7) | 35 | (26.7) | 54 | (28.3) | |

| >USD 80 k | 20 | (33.3) | 20 | (15.3) | 40 | (20.9) | |

| Not reported | 5 | (8.3) | 13 | (9.9) | 18 | (9.4) | |

| Current work status | |||||||

| Employed | 36 | (60.0) | 87 | (66.4) | 123 | (64.4) | 0.646 |

| Unemployed | 10 | (16.7) | 17 | (13.0) | 27 | (14.1) | |

| Not in workforce | 14 | (23.3) | 27 | (20.6) | 41 | (21.5) | |

| Changes in work status since COVID-19 | |||||||

| Change tasks or work less | 18 | (30.0) | 37 | (28.2) | 55 | (28.8) | 0.804 |

| Stopped working | 14 | (23.3) | 23 | (17.6) | 37 | (19.4) | 0.43 |

| Health insurance (not mutually exclusive) | |||||||

| None | 3 | (5.0) | 13 | (9.9) | 16 | (8.4) | 0.254 |

| Private | 25 | (41.7) | 35 | (26.7) | 60 | (31.4) | 0.039 |

| Public/government-funded | 16 | (26.7) | 55 | (42.0) | 71 | (37.2) | 0.042 |

| Purchased | 9 | (15.0) | 16 | (12.2) | 25 | (13.1) | 0.596 |

| Military | 2 | (3.3) | 7 | (5.3) | 9 | (4.7) | 0.722 |

| Other types | 7 | (11.7) | 5 | (3.8) | 12 | (6.3) | 0.053 |

| Been to the Emergency room since having long COVID or COVID-19 | |||||||

| Yes | 14 | (23.3) | 51 | (38.9) | 65 | (34.0) | 0.045 |

| No | 46 | (76.7) | 79 | (60.3) | 125 | (65.4) | |

| General health | |||||||

| Excellent/very good | 15 | (25.0) | 45 | (35.2) | 60 | (31.9) | 0.355 |

| Good | 24 | (40.0) | 47 | (36.7) | 71 | (37.8) | |

| Fair/poor | 21 | (35.0) | 36 | (28.1) | 57 | (30.3) | |

| Received at least one dose of first COVID-19 vaccine | |||||||

| Yes | 51 | (85.0) | 87 | (69.0) | 138 | (74.2) | 0.021 |

| No | 9 | (15.0) | 39 | (31.0) | 48 | (25.8) | |

| Obtained a flu shot in past 12 months | |||||||

| Yes | 38 | (63.3) | 64 | (51.2) | 102 | (55.1) | 0.120 |

| No | 22 | (36.7) | 61 | (48.8) | 83 | (44.9) | |

| (a) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Total | Fischer’s | ||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | Exact | |

| Total | 44 | (37.0) | 75 | (63.0) | 119 | p-Value * | |

| Careful about who you tell that you have long COVID | |||||||

| Rarely | 20 | (45.5) | 28 | (37.8) | 48 | (40.7) | 0.529 |

| Sometimes | 12 | (27.3) | 28 | (37.8) | 40 | (33.9) | |

| Always/Often | 12 | (27.3) | 18 | (24.3) | 30 | (25.4) | |

| Regret having told some people that you have long COVID | |||||||

| Rarely | 20 | (45.5) | 33 | (46.5) | 53 | (46.1) | 0.22 |

| Sometimes | 19 | (43.2) | 22 | (31.) | 41 | (35.7) | |

| Always/Often | 5 | (11.4) | 16 | (22.5) | 21 | (18.3) | |

| Misunderstood for having long COVID, a “hidden” disability | |||||||

| Rarely | 16 | (36.4) | 27 | (37.5) | 43 | (37.1) | 0.47 |

| Sometimes | 14 | (31.8) | 29 | (40.3) | 43 | (37.1) | |

| Always/Often | 14 | (31.8) | 16 | (22.2) | 30 | (25.9) | |

| Supported by friends and family about having long COVID | |||||||

| Rarely | 5 | (11.6) | 12 | (16.4) | 17 | (14.7) | 0.016 |

| Sometimes | 24 | (55.8) | 21 | (28.8) | 45 | (38.8) | |

| Always/Often | 14 | (32.6) | 40 | (54.8) | 54 | (46.6) | |

| (b) | |||||||

| White | Black | Total | Fischer’s | ||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | Exact | |

| Total | 44 | (37.0) | 75 | (63.0) | 119 | p-Value * | |

| Doing regular household chores or other daily activities | |||||||

| Rarely | 4 | (9.1) | 9 | (12.2) | 13 | (11.0) | 0.282 |

| Sometimes | 22 | (50.0) | 46 | (62.2) | 68 | (57.6) | |

| Always/often | 16 | (36.4) | 17 | (23.0) | 33 | (28.0) | |

| Not applicable | 2 | (4.5) | 2 | (2.7) | 4 | (3.4) | |

| Caring for children or other family | |||||||

| Rarely | 12 | (27.3) | 14 | (18.9) | 26 | (22.0) | 0.175 |

| Sometimes | 10 | (22.7) | 31 | (41.9) | 41 | (34.7) | |

| Always/often | 7 | (15.9) | 19 | (25.7) | 26 | (22.0) | |

| Not applicable | 15 | (34.1) | 10 | (13.5) | 25 | (21.2) | |

| Visiting family | |||||||

| Rarely | 15 | (34.1) | 14 | (18.9) | 29 | (24.6) | 0.007 |

| Sometimes | 12 | (27.3) | 43 | (58.1) | 55 | (46.6) | |

| Always/often | 14 | (31.8) | 15 | (20.3) | 29 | (24.6) | |

| Not applicable | 3 | (6.8) | 2 | (2.7) | 5 | (4.2) | |

| Spending time with friends | |||||||

| Rarely | 8 | (18.2) | 16 | (21.6) | 24 | (20.3) | 0.057 |

| Sometimes | 17 | (38.6) | 41 | (55.4) | 58 | (49.2) | |

| Always/often | 18 | (40.9) | 15 | (20.3) | 33 | (28.0) | |

| Not applicable | 1 | (2.3) | 2 | (2.7) | 3 | (2.5) | |

| Working or being employed for pay | |||||||

| Rarely | 9 | (20.5) | 22 | (30.1) | 31 | (26.5) | 0.09 |

| Sometimes | 10 | (22.7) | 25 | (34.2) | 35 | (29.9) | |

| Always/Often | 18 | (40.9) | 17 | (23.3) | 35 | (29.9) | |

| Not applicable | 7 | (15.9) | 9 | (12.3) | 16 | (13.7) | |

| Volunteering | |||||||

| Rarely | 8 | (18.6) | 18 | (25.0) | 26 | (22.6) | 0.005 |

| Sometimes | 9 | (20.9) | 29 | (40.3) | 38 | (33.0) | |

| Always/often | 17 | (39.5) | 10 | (13.9) | 27 | (23.5) | |

| Not applicable | 9 | (20.9) | 15 | (20.8) | 24 | (20.9) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pilkington, W.; Bauer, B.E.; Doherty, I.A. Living with Long COVID in a Southern State: A Comparison of Black and White Residents of North Carolina. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020279

Pilkington W, Bauer BE, Doherty IA. Living with Long COVID in a Southern State: A Comparison of Black and White Residents of North Carolina. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020279

Chicago/Turabian StylePilkington, William, Brooke E. Bauer, and Irene A. Doherty. 2025. "Living with Long COVID in a Southern State: A Comparison of Black and White Residents of North Carolina" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020279

APA StylePilkington, W., Bauer, B. E., & Doherty, I. A. (2025). Living with Long COVID in a Southern State: A Comparison of Black and White Residents of North Carolina. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020279