Musculoskeletal Complaints Among Female Childcare Workers in German Daycare Centres—A Survey Study with a Comparison Group

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How frequently do female childcare workers in daycare centres report musculoskeletal complaints, particularly in the knee joint, compared to a female comparison group from the general population?

- To what extent does the job of a female childcare worker in daycare centres increase the risk of musculoskeletal complaints, especially in the knee joint, compared to a female comparison group from the general population?

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Dependent and Independent Variables

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

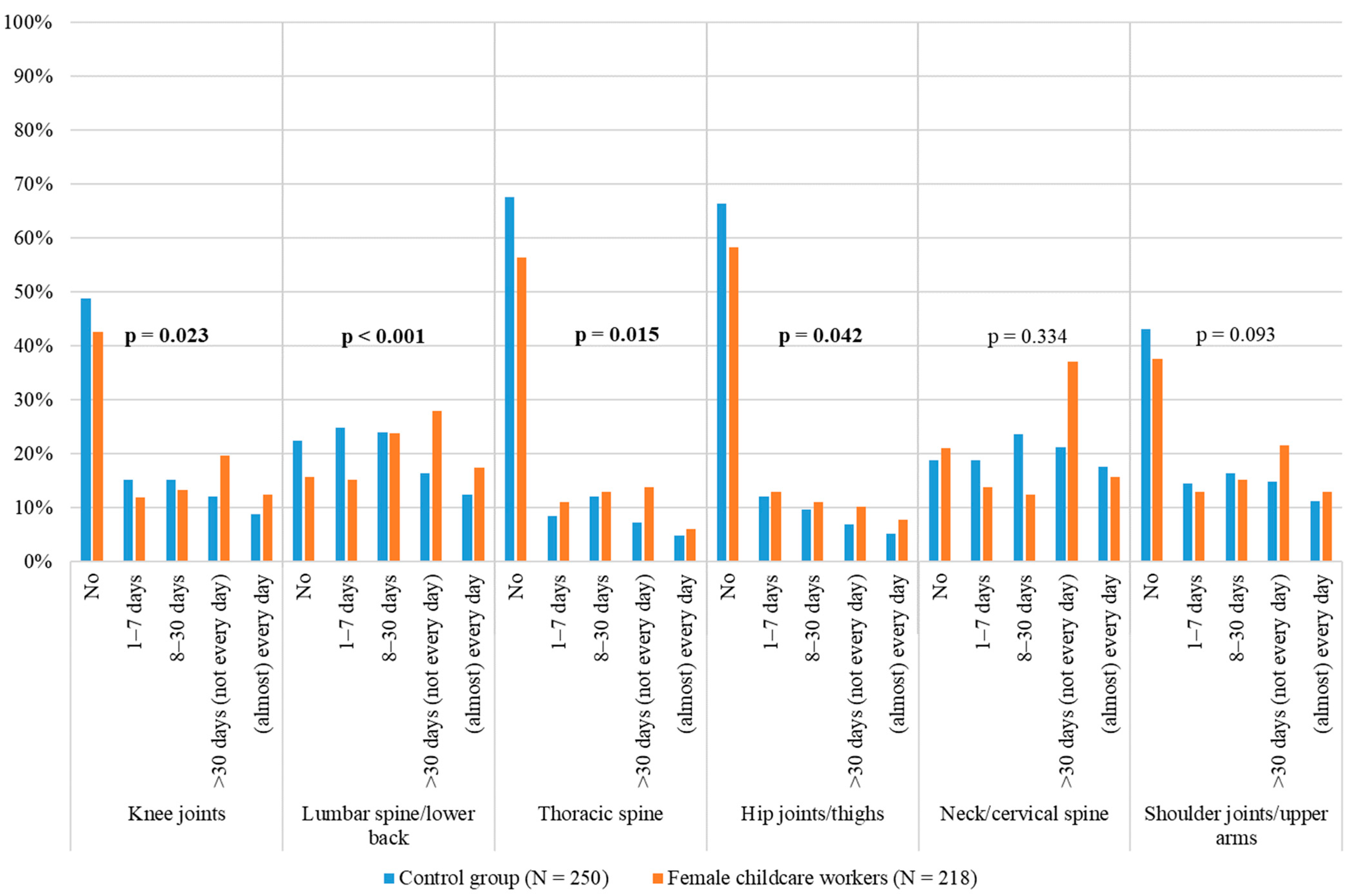

3.2. Results Regarding Musculoskeletal Complaints

4. Discussion

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Laudanski, A.F.; Buchman-Pearle, J.M.; Acker, S.M. Quantifying high flexion postures in occupational childcare as they relate to the potential for increased risk of knee osteoarthritis. Ergonomics 2022, 65, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtermann, A.; Fjeldstad Hendriksen, P.; Greby Schmidt, K.; Jagd Svendsen, M.; Nørregaard Rasmussen, C.D. Physical Work Demands of Childcare Workers in Denmark: Device-Based Measurements and Workplace Observations Among 199 Childcare Workers from 16 Day Nurseries. Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2020, 64, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakob, N.; Klewer, J. Analyse der Belastungen und Beanspruchungen von Erziehern in Kindertageseinrichtungen. HeilberufeScience 2013, 4, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, P.; Stranzinger, J.; Nienhaus, A.; Kozak, A. Musculoskeletal Symptoms and Risk of Burnout in Child Care Workers—A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinn-Behrendt, A.; Sica, L.; Bopp, V.; Bruder, R.; Brehmen, M.; Groneberg, D.; Burford, E.-M.; Schreiber, P.; Weber, B.; Ellegast, R. Projekt ErgoKiTa-Prävention von Muskel-Skelett-Belastungen bei Erzieherinnen und Erziehern in Kindertageseinrichtungen; German Social Accident Insurance (DGUV): Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Viernickel, S.; Voss, A. Strukturqualität und Erzieher_Innengesundheit in Kindertageseinrichtungen (STEGE). Wissenschaftlicher Abschlussbericht. Manuskript. Berlin. 2013. Available online: https://www.bildungsserver.de/onlineressource.html?onlineressourcen_id=50502 (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Doan, J.; Awosoga, O.; Provost, T.; Blinch, J.; Hudson, J. Perceived affordances and postures for lifting in child care. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2017, 18, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaj, A.; Diesbourg, T.; Dumas, G.; Plamondon, A.; Mercheri, H.; Larue, C. Posture and lifting exposures for daycare workers. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2016, 54, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaj, A.; Diesbourg, T.L.; Dumas, G.A.; Plamondon, A.; Mecheri, H. Comparison of lifting and bending demands of the various tasks performed by daycare workers. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2019, 69, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnan, L.; Arandia, G.; Bateman, L.A.; Vaughn, A.; Smith, N.; Ward, D. The Health and Working Conditions of Women Employed in Child Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, C.D.N.; Sørensen, O.H.; van der Beek, A.J.; Holtermann, A. The effect of training for a participatory ergonomic intervention on physical exertion and musculoskeletal pain among childcare workers (the TOY project)—A wait-list cluster-randomized controlled trial. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2020, 46, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schønheyder, M.; Dietz, M.U.; Schmidt, K.G.; Svendsen, M.J.; Sørensen, O.H.; Holtermann, A.; Nørregaard Rasmussen, C.D. Risks, solutions and implementation of a participatory ergonomic intervention in 16 day nurseries: A process evaluation of the TOY wait-list cluster-randomized controlled trial. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.Z.; Gerberich, S.G. Disabling injuries to childcare workers in Minnesota, 1985 to 1990. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1993, 35, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar]

- King, P.M.; Gratz, R.; Scheuer, G.; Claffey, A. The ergonomics of child care: Conducting worksite analyses. Work 1996, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, S.; Tabuchi, T.; Tainaka, H.; Miyajima, K.; Matsunaga, I.; Kosaka, H.; Andoh, K.; Seo, A. Load on the low back of teachers in nursery schools. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 1996, 68, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, B.D. Intervention for Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Child-Care Workers. Pediatrics 1994, 94, 1077–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Shimaoka, M.; Hiruta, S.; Ono, Y.; Nonaka, H.; Hjelm, E.W.; Hagberg, M. A comparative study of physical work load in Japanese and Swedish nursery school teachers. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1997, 77, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, N.G.; Piotrkowski, C.S.; Curbow, B.; Graville, S.; Kushnir, T.; Owen, B.D. Occupational Health and Safety Issues in Child-Care Work. Pediatrics 1994, 94, 1079–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, P.; Kersten, J.F.; Stranzinger, J.; Nienhaus, A. The effect of effort-reward imbalance on the health of childcare workers in Hamburg: A longitudinal study. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2017, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelsmann Stiftung Ländermonitor Frühkindliche Bildung. Geschlecht des Pädagogischen KiTa-Personals. KiTas mit Horten. Available online: https://www.laendermonitor.de/de/vergleich-bundeslaender-daten/personal-und-einrichtungen/paedagogisches-personal/geschlecht-1 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin; Berufsgenossenschaft für Gesundheitsdienst und Wohlfahrtspflege. Nordischer Fragebogen zu Muskel-Skelett-Beschwerden (NFB*MSB). Version zur Erprobung. Baua Praxis 2021. Available online: https://www.bgw-online.de/bgw-online-de/service/medien-arbeitshilfen/medien-center/arbeitsmedizin/nordischer-fragebogen-zu-muskel-skelett-beschwerden-nfb-msb--22034 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Nübling, M.; Stößel, U.; Hasselhorn, H.-M.; Michaelis, M.; Hofmann, F. Methoden zur Erfassung psychischer Belastungen—Erprobung eines Messinstrumentes (COPSOQ); Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Dortmund, Germany; Berlin, Germany; Dresden, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Adipositas Gesellschaft BMI-Rechner. Available online: https://adipositas-gesellschaft.de/bmi/ (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Rasmussen, C.D.N.; Hendriksen, P.R.; Svendsen, M.J.; Ekner, D.; Hansen, K.; Sørensen, O.H.; Svendsen, S.W.; van der Beek, A.J.; Holtermann, A. Improving work for the body—A participatory ergonomic intervention aiming at reducing physical exertion and musculoskeletal pain among childcare workers (the TOY-project): Study protocol for a wait-list cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials 2018, 19, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akko, D.P. Krankenstand in Berufen der Kinderbetreuung und-Erziehung. Eine Auswertung von Krankenkassendaten; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bock-Famulla, K.; Berg, E.; Girndt, A.; Akko, D.P.; Krause, M.; Schütz, J. Länderreport Frühkindliche Bildungssysteme 2023; Transparenz Schaffen—Governance Stärken; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Comparison Group n = 250 (%) | Childcare Workers n = 218 (%) | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40 to 49 years | 75 (30.0) | 82 (37.6) | 0.007 |

| 50 to 59 years | 94 (37.6) | 93 (42.7) | ||

| 60 to 67 years | 81 (32.4) | 43 (19.7) | ||

| BMI 2 | Underweight (<18.5) | 8 (3.2) | 2 (0.9) | 0.258 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 127 (50.8) | 112 (51.4) | ||

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 69 (27.6) | 56 (25.7) | ||

| Grade I obesity (30–34.9) | 30 (12.0) | 33 (15.1) | ||

| Grade II obesity (35–39.9) | 12 (4.8) | 7 (3.2) | ||

| Grade III obesity (>40) | 4 (1.6) | 8 (3.7) | ||

| Children in the household | No children | 150 (60.0) | 112 (51.4) | 0.228 |

| 1 child | 41 (16.4) | 43 (19.7) | ||

| 2 children | 48 (19.2) | 47 (21.6) | ||

| 3+ children | 11 (4.4) | 16 (7.3) | ||

| Sports/exercise: weekly activity | No sporting activity | 38 (15.2) | 37 (17.0) | 0.034 |

| <1 h | 38 (15.2) | 37 (17.0) | ||

| 1–2 h | 66 (26.4) | 76 (34.9) | ||

| 2–4 h | 68 (27.2) | 34 (15.6) | ||

| >4 h | 40 (16.0) | 34 (15.6) | ||

| Smoking | Yes, daily, or occasionally | 43 (17.2) | 47 (21.6) | 0.494 |

| Ex-smoker | 86 (34.4) | 65 (29.8) | ||

| Never | 120 (48.0) | 104 (47.7) | ||

| Not specified | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Educational qualification | Basic education 3 | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | 0.052 |

| Secondary school certificate 4 | 17 (6.8) | 8 (3.7) | ||

| Middle maturity | 67 (26.8) | 82 (37.6) | ||

| Qualification to enter higher education | 159 (63.6) | 119 (54.6) | ||

| Other educational qualification | 5 (2.0) | 8 (3.7) | ||

| Vocational training and instruction | Currently in vocational training 5 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| No vocational qualification | 5 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Vocational training and instruction 6 | 130 (52.0) | 166 (76.1) | ||

| Higher education 7 | 103 (41.2) | 43 (19.7) | ||

| Other vocational qualification | 11 (4.4) | 7 (3.2) | ||

| Job satisfaction | Very low | 57 (22.8) | 56 (25.7) | 0.009 |

| Low | 55 (22.0) | 66 (30.3) | ||

| High | 65 (26.0) | 60 (27.5) | ||

| Very high | 73 (29.2) | 36 (16.5) | ||

| Variable | Comparison Group n = 250 (%) | Childcare Workers n = 218 (%) | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck/cervical spine | Yes | 95 (38.0) | 125 (57.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 155 (62.0) | 93 (42.7) | ||

| Shoulder joints/upper arms | Yes | 73 (29.2) | 92 (42.2) | 0.003 |

| No | 177 (70.8) | 126 (57.8) | ||

| Thoracic spine | Yes | 46 (18.4) | 58 (26.6) | 0.033 |

| No | 204 (81.6) | 160 (73.4) | ||

| Knee joints | Yes | 67 (26.8) | 85 (39.0) | 0.005 |

| No | 183 (73.2) | 133 (61.0) | ||

| Lumbar spine/lower back | Yes | 99 (39.6) | 147 (67.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 151 (60.4) | 71 (32.6) | ||

| Hip joints/thighs | Yes | 38 (15.2) | 55 (25.2) | 0.007 |

| No | 212 (84.8) | 163 (74.8) | ||

| Variable | Neck/Cervical Spine | Shoulder Joints/Upper Arms | Thoracic Spine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | ||

| Group | Comparison group (ref.) 2/ childcare worker | 1.9 (1.27–2.85) | 0.002 | 1.7 (1.12–2.52) | 0.012 | 1.3 (0.84–2.15) | 0.225 |

| BMI | Normal weight (ref.) 2 | – | 0.637 | – | 0.813 | – | 0.711 |

| Underweight | 0.3 (0.06–1.59) | 0.156 | 0.6 (0.11–2.93) | 0.494 | 0.8 (0.15–4.04) | 0.771 | |

| Overweight | 1.2 (0.73–1.91) | 0.495 | 1.3 (0.78–2.03) | 0.352 | 1.2 (0.66–2.06) | 0.588 | |

| Grade I obesity | 1.2 (0.65–2.24) | 0.545 | 1.4 (0.75–2.50) | 0.312 | 1.6 (0.82–3.22) | 0.164 | |

| Grade II obesity | 0.8 (0.28–2.12) | 0.605 | 0.9 (0.32–2.72) | 0.907 | 1.5 (0.47–4.56) | 0.506 | |

| Grade III obesity | 1.0 (0.27–3.43) | 0.945 | 1.1 (0.30–3.70) | 0.934 | 1.9 (0.55–6.91) | 0.303 | |

| Age | 40–49 years (ref.) 2 | – | 0.454 | – | 0.449 | – | 0.002 |

| 50–59 years | 1.3 (0.78–2.12) | 0.328 | 1.4 (0.82–2.26) | 0.226 | 0.8 (0.47–1.39) | 0.440 | |

| 60–67 | 1.0 (0.53–1.79) | 0.939 | 1.4 (0.74–2.55) | 0.310 | 0.3 (0.12–0.58) | <0.001 | |

| Sport/week | No sport (ref.) 2 | – | 0.346 | – | 0.848 | – | 0.754 |

| <1 h | 1.3 (0.63–2.50) | 0.524 | 1.2 (0.58–2.31) | 0.683 | 0.9 (0.38–1.99) | 0.736 | |

| 1–2 h | 1.5 (0.82–2.75) | 0.184 | 1.1 (0.59–1.97) | 0.816 | 1.2 (0.61–2.51) | 0.562 | |

| 2–4 h | 1.1 (0.58–2.16) | 0.736 | 0.9 (0.46–1.79) | 0.785 | 1.4 (0.64–3.00) | 0.405 | |

| >4 h | 0.8 (0.40–1.64) | 0.551 | 1.3 (0.65–2.68) | 0.437 | 1.0 (0.43–2.34) | 0.989 | |

| Children | No children in household (ref.) 2 | – | 0.281 | – | 0.902 | – | 0.780 |

| 1 child in household | 0.8 (0.45–1.41) | 0.440 | 1.0 (0.55–1.72) | 0.916 | 0.7 (0.38–1.40) | 0.342 | |

| 2 children in household | 0.9 (0.49–1.60) | 0.684 | 1.1 (0.60–1.97) | 0.772 | 0.8 (0.42–1.51) | 0.480 | |

| 3+ children in household | 2.1 (0.81–5.23) | 0.131 | 1.4 (0.55–3.43) | 0.495 | 0.8 (0.27–2.26) | 0.656 | |

| Job satisfaction | Very low (ref.) 2 | – | <0.001 | – | 0.002 | – | 0.011 |

| Low | 0.5 (0.29–0.89) | 0.018 | 0.5 (0.29–0.87) | 0.014 | 0.9 (0.52–1.72) | 0.855 | |

| High | 0.3 (0.19–0.57) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.25–0.75) | 0.003 | 0.4 (0.22–0.83) | 0.012 | |

| Very high | 0.2 (0.09–0.31) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.20–0.65) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.22–0.89) | 0.022 | |

| Variable | Knee Joints | Lumbar Spine/Lower Back | Hip Joints/Thighs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | ||

| Group | Comparison group (ref.) 2/ childcare worker | 1.8 (1.19–2.81) | 0.006 | 3.2 (2.09–4.80) | <0.001 | 1.6 (0.98–2.60) | 0.062 |

| BMI | Normal weight (ref.) 2 | – | 0.002 | – | 0.072 | – | 0.728 |

| Underweight | 0.9 (0.18–4.89) | 0.934 | 0.3 (0.05–1.71) | 0.173 | 0.5 (0.06–4.22) | 0.508 | |

| Overweight | 1.5 (0.89–2.45) | 0.132 | 1.6 (0.95–2.53) | 0.078 | 0.9 (0.47–1.56) | 0.606 | |

| Grade I obesity | 2.9 (1.59–5.46) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.05–3.73) | 0.034 | 1.1 (0.51–2.18) | 0.889 | |

| Grade II obesity | 4.6 (1.63–13.00) | 0.004 | 2.3 (0.83–6.61) | 0.107 | 2.0 (0.66–5.81) | 0.224 | |

| Grade III obesity | 3.3 (0.91–11.82) | 0.070 | 1.1 (0.31–3.87) | 0.880 | 1.5 (0.38–5.54) | 0.585 | |

| Age | 40–49 years (ref.) 2 | – | 0.006 | – | 0.499 | – | 0.053 |

| 50–59 years | 2.0 (1.15–3.38) | 0.013 | 1.3 (0.81–2.25) | 0.255 | 2.0 (1.07–3.60) | 0.029 | |

| 60–67 | 2.8 (1.47–5.46) | 0.002 | 1.3 (0.72–2.49) | 0.357 | 1.2 (0.56–2.50) | 0.657 | |

| Sport/week | No sport (ref.) 2 | – | 0.317 | – | 0.393 | – | 0.375 |

| <1 h | 2.2 (1.04–4.67) | 0.040 | 1.5 (0.75–3.14) | 0.239 | 1.2 (0.51–2.62) | 0.739 | |

| 1–2 h | 1.8 (0.92–3.55) | 0.086 | 1.2 (0.63–2.14) | 0.631 | 1.3 (0.63–2.59) | 0.506 | |

| 2–4 h | 1.6 (0.79–3.41) | 0.186 | 0.9 (0.45–1.69) | 0.682 | 0.6 (0.27–1.48) | 0.291 | |

| >4 h | 1.9 (0.86–4.15) | 0.113 | 1.5 (0.73–3.05) | 0.273 | 0.8 (0.32–1.91) | 0.594 | |

| Children | No children in household (ref.) 2 | – | 0.076 | – | 0.390 | – | 0.956 |

| 1 child in household | 2.2 (1.20–3.89) | 0.010 | 0.7 (0.38–1.22) | 0.202 | 0.9 (0.46–1.78) | 0.778 | |

| 2 children in household | 1.2 (0.62–2.20) | 0.639 | 0.9 (0.49–1.66) | 0.741 | 0.8 (0.41–1.71) | 0.627 | |

| 3+ children in household | 1.3 (0.47–3.52) | 0.624 | 0.5 (0.20–1.32) | 0.169 | 0.8 (0.24–2.67) | 0.709 | |

| Job satisfaction | Very low (ref.) 2 | – | 0.257 | – | <0.001 | – | 0.005 |

| Low | 0.7 (0.39–1.23) | 0.208 | 1.1 (0.64–2.02) | 0.665 | 0.8 (0.42–1.47) | 0.443 | |

| High | 0.7 (0.38–1.19) | 0.173 | 0.4 (0.25–0.78) | 0.004 | 0.9 (0.49–1.67) | 0.753 | |

| Very high | 0.5 (0.30–1.01) | 0.054 | 0.4 (0.23–0.74) | 0.003 | 0.2 (0.08–0.50) | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dauer, R.; Schablon, A.; Nienhaus, A. Musculoskeletal Complaints Among Female Childcare Workers in German Daycare Centres—A Survey Study with a Comparison Group. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020270

Dauer R, Schablon A, Nienhaus A. Musculoskeletal Complaints Among Female Childcare Workers in German Daycare Centres—A Survey Study with a Comparison Group. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020270

Chicago/Turabian StyleDauer, Roxana, Anja Schablon, and Albert Nienhaus. 2025. "Musculoskeletal Complaints Among Female Childcare Workers in German Daycare Centres—A Survey Study with a Comparison Group" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020270

APA StyleDauer, R., Schablon, A., & Nienhaus, A. (2025). Musculoskeletal Complaints Among Female Childcare Workers in German Daycare Centres—A Survey Study with a Comparison Group. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020270