Perceived Harm to Pet Health Associated with Human Quality of Life After a Public Health Disaster

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Perceived Pet Health

2.2. Human Consumption of Unfiltered Tap Water

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Unfiltered Tap Water Consumption by Humans and Perceived Pet Health

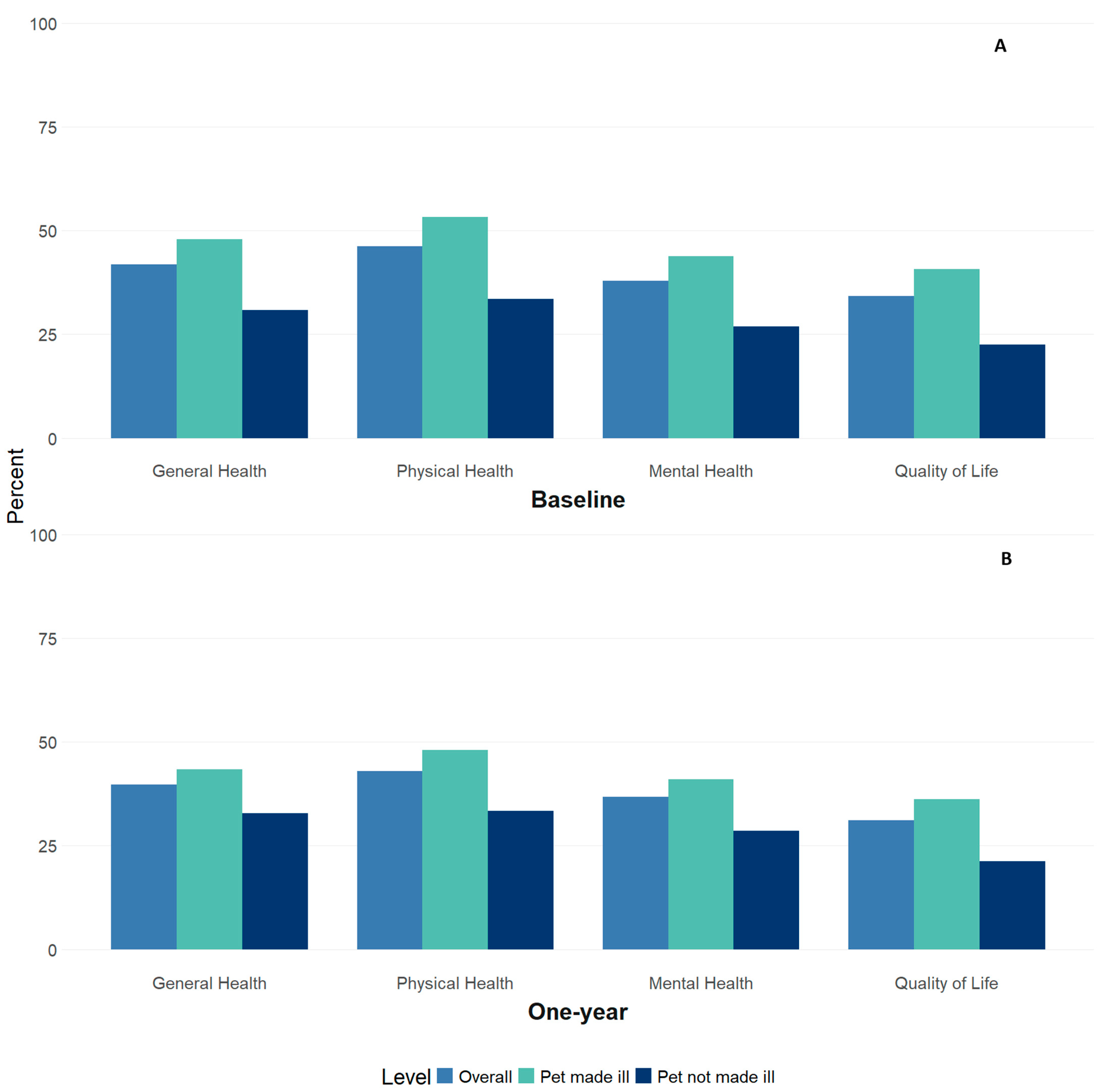

3.2. Perceived Pet Health and Human Health Outcomes at Baseline

3.3. Perceived Pet Health and Human Health Outcomes at Follow-Up

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About One Health. One Health. 21 November 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/about/index.html (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Robbiati, C.; Milano, A.; Declich, S.; Di Domenico, K.; Mancini, L.; Pizzarelli, S.; D’Angelo, F.; Riccardo, F.; Scavia, G.; Dente, M.G. One health adoption within prevention, preparedness and response to health threats: Highlights from a scoping review. One Health 2023, 17, 100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, E.; Krause-Parello, C.A. Companion animals and human health: Benefits, challenges, and the road ahead for human-animal interaction. Rev. Sci. Tech. Int. Off Epizoot. 2018, 37, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNicholas, J.; Gilbey, A.; Rennie, A.; Ahmedzai, S.; Dono, J.A.; Ormerod, E. Pet ownership and human health: A brief review of evidence and issues. BMJ 2005, 331, 1252–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.F.; Soares, J.P.; Cortinhas, A.; Silva, L.; Cardoso, L.; Pires, M.A.; Mota, M.P. Pet’s influence on humans’ daily physical activity and mental health: A meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1196199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.J.; Ng, A.; Ursano, R.J.; Holloway, H.; Fullerton, C.; Casper, J. Psychological impact of the animal-human bond in disaster preparedness and response. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2004, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosthuizen, K.; Haase, B.; Ravulo, J.; Lomax, S.; Ma, G. The role of human–animal bonds for people experiencing crisis situations. Animals 2023, 13, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, L.C.; Grindem, C.B.; Corbett, W.T.; Cullins, L.; Hunter, J.L. Pet dogs as sentinels for environmental contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2001, 274, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council. Animals as Sentinels of Environmental Health Hazards; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, S.R. Sentinel Animals (Dogs) as Predictors of Childhood Exposure to Environmental Lead Contamination: Observations on Preliminary Results. In In Situ Evaluation of Biological Hazards of Environmental Pollutants; Sandhu, S.S., Lower, W.R., de Serres, F.J., Suk, W.A., Tice, R.R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. Lead-Laced Water in Flint: A Step-By-Step Look at the Makings of a Crisis. NPR. 20 April 2016. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/04/20/465545378/lead-laced-water-in-flint-a-step-by-step-look-at-the-makings-of-a-crisis (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Ruckart, P.Z.; Ettinger, A.S.; Hanna-Attisha, M.; Jones, N.; Davis, S.I.; Breysse, P.N. The Flint water crisis: A coordinated public health emergency response and recovery initiative. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2019, 25 (Suppl. S1), S84–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, K.J.; Tang, M.; Edwards, M.A. Flint water crisis caused by interrupted corrosion control: Investigating “ground zero” home. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 2007–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Land, L. The Flint Water Crisis affected pets also. The Flint Courier News. 24 May 2020. Available online: https://theflintcouriernews.com/the-flint-water-crisis-affected-pets-also/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Langlois, D.K.; Kaneene, J.B.; Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan, V.; Daniels, B.L.; Mejia-Abreu, H.; Frank, N.A.; Buchweitz, J.P. Investigation of blood lead concentrations in dogs living in Flint, Michigan. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2017, 251, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Lead. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/95222 (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Jones, N.; Dotson, K.; Smith, K.D.; Reynolds, L.; Key, K.; Hanna-Attisha, M. The impact of community engagement in the design and implementation of the Flint Registry. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2024, 18, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Revicki, D.A.; Spritzer, K.L.; Cella, D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, S.R.; Rhodes, J.E.; Zwiebach, L.; Chan, C.S. The impact of pet loss on the perceived social support and psychological distress of hurricane survivors. J. Trauma. Stress 2009, 22, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Saeki, J.; Hayama, S.I.; Kass, P.H. Effect of pets on human behavior and stress in disaster. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonger, R. Flint Issues Boil Water Advisory for Section of the City After Positive Test for Total Coliform Bacteria. Mlive. 6 September 2014. Available online: https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2014/09/flint_issues_boil_water_adviso.html (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Fonger, R. State Says Flint River Water Meets All Standards But More than Twice the Hardness of Lake Water. Mlive. 23 May 2014. Available online: https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2014/05/state_says_flint_river_water_m.html (accessed on 7 October 2024).

| Characteristic | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| n | 3264 | |

| Mean Age (standard deviation) | 47.3 | 15.3 |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1575 | 48.3 |

| Black | 1280 | 39.2 |

| Other * | 67 | 2.1 |

| Multiracial | 181 | 5.6 |

| Latinx | 161 | 4.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 2236 | 68.5 |

| Male | 1020 | 31.3 |

| Other | 8 | 0.3 |

| Household Income | ||

| <USD 12,000 per year | 1163 | 35.6 |

| USD 12,000–<USD 25,000 | 882 | 27.0 |

| USD 25,000–<USD 50,000 | 770 | 23.6 |

| USD 50,000–<USD 75,000 | 253 | 7.8 |

| USD 75,000 and higher | 196 | 6.0 |

| Time living in Flint during the water crisis | ||

| Less than the full 18 months | 279 | 8.6 |

| The full 18 months | 2985 | 91.5 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 953 | 29.2 |

| Widowed | 199 | 6.1 |

| Divorced | 613 | 18.8 |

| Separated | 147 | 4.5 |

| Never married/single | 1352 | 41.4 |

| Drank unfiltered tap water during the water crisis | ||

| Every day | 2744 | 84.1 |

| Less than every day | 313 | 9.6 |

| Never | 207 | 6.3 |

| Pet Made Ill | Pet Not Made Ill | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived pet health (n = 3264) | 2099 (64.3) | 1165 (35.7) | - |

| Frequency of drinking unfiltered tap water during the water switch | |||

| Every day | 1843 (67.2) | 901 (32.8) | 3.12 (2.33–4.23) |

| Less than every day | 177 (56.6) | 136 (43.4) | 2.05 (1.42–3.00) |

| Never | 79 (38.2) | 128 (61.8) | Reference |

| Self-Reported Health Outcomes | Denominator | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 3264) | ||

| General Health Fair or Poor | 3238 | 1.92 (1.63–2.26) |

| Physical Health Fair or Poor | 3216 | 2.15 (1.83–2.52) |

| Mental Health Fair or Poor | 3220 | 1.97 (1.67–2.32) |

| Quality of Life Fair or Poor | 3231 | 2.16 (1.82–2.57) |

| Baseline for 1-Year Follow-up Sample (n = 1172) | ||

| General Health Fair or Poor | 1171 | 1.83 (1.38–2.43) |

| Physical Health Fair or Poor | 1165 | 2.12 (1.61–2.79) |

| Mental Health Fair or Poor | 1166 | 1.87 (1.41–2.49) |

| Quality of Life Fair or Poor | 1169 | 2.57 (1.89–3.50) |

| 1-Year Follow-up (n = 1172) | ||

| General Health Fair or Poor | 1171 | 1.32 (1.00–1.74) |

| Physical Health Fair or Poor | 1165 | 1.60 (1.22–2.10) |

| Mental Health Fair or Poor | 1166 | 1.50 (1.14–1.98) |

| Quality of Life Fair or Poor | 1169 | 1.92 (1.42–2.60) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haggerty, D.K.; Wahl, R.; Jones, N.; LaChance, J.; Hanna, M. Perceived Harm to Pet Health Associated with Human Quality of Life After a Public Health Disaster. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020250

Haggerty DK, Wahl R, Jones N, LaChance J, Hanna M. Perceived Harm to Pet Health Associated with Human Quality of Life After a Public Health Disaster. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020250

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaggerty, Diana K., Robert Wahl, Nicole Jones, Jenny LaChance, and Mona Hanna. 2025. "Perceived Harm to Pet Health Associated with Human Quality of Life After a Public Health Disaster" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020250

APA StyleHaggerty, D. K., Wahl, R., Jones, N., LaChance, J., & Hanna, M. (2025). Perceived Harm to Pet Health Associated with Human Quality of Life After a Public Health Disaster. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020250