Physical and Mental Health of Caregivers and Educators of Preschool-Aged Children: Identifying Benefits and Barriers to Outdoor Time, How Outdoor Time Can Make a Difference for Health Equity, and Why Income Matters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Procedures and Application of Theoretical Framework

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Demographic Variables

2.4.2. Outdoor Time Exposure

2.4.3. Physical Health Outcomes

2.4.4. Mental Health Outcomes

2.4.5. Benefits and Barriers of Outdoor Time and Importance, Availability, and Accessibility of Community Resources for Outdoor Time

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics

3.2. Association of Physical and Mental Health Constructs with Weekly Outdoor Time and Income

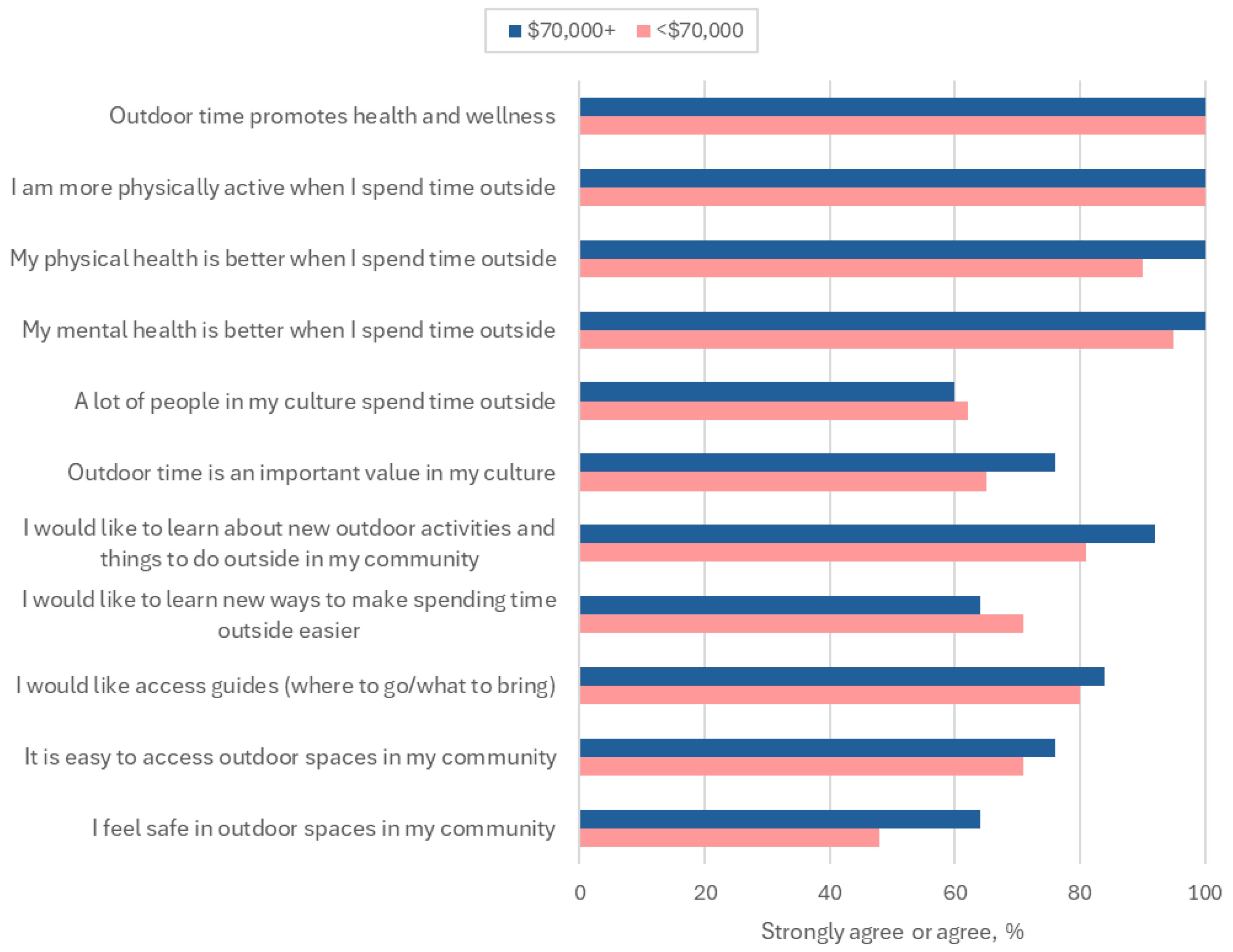

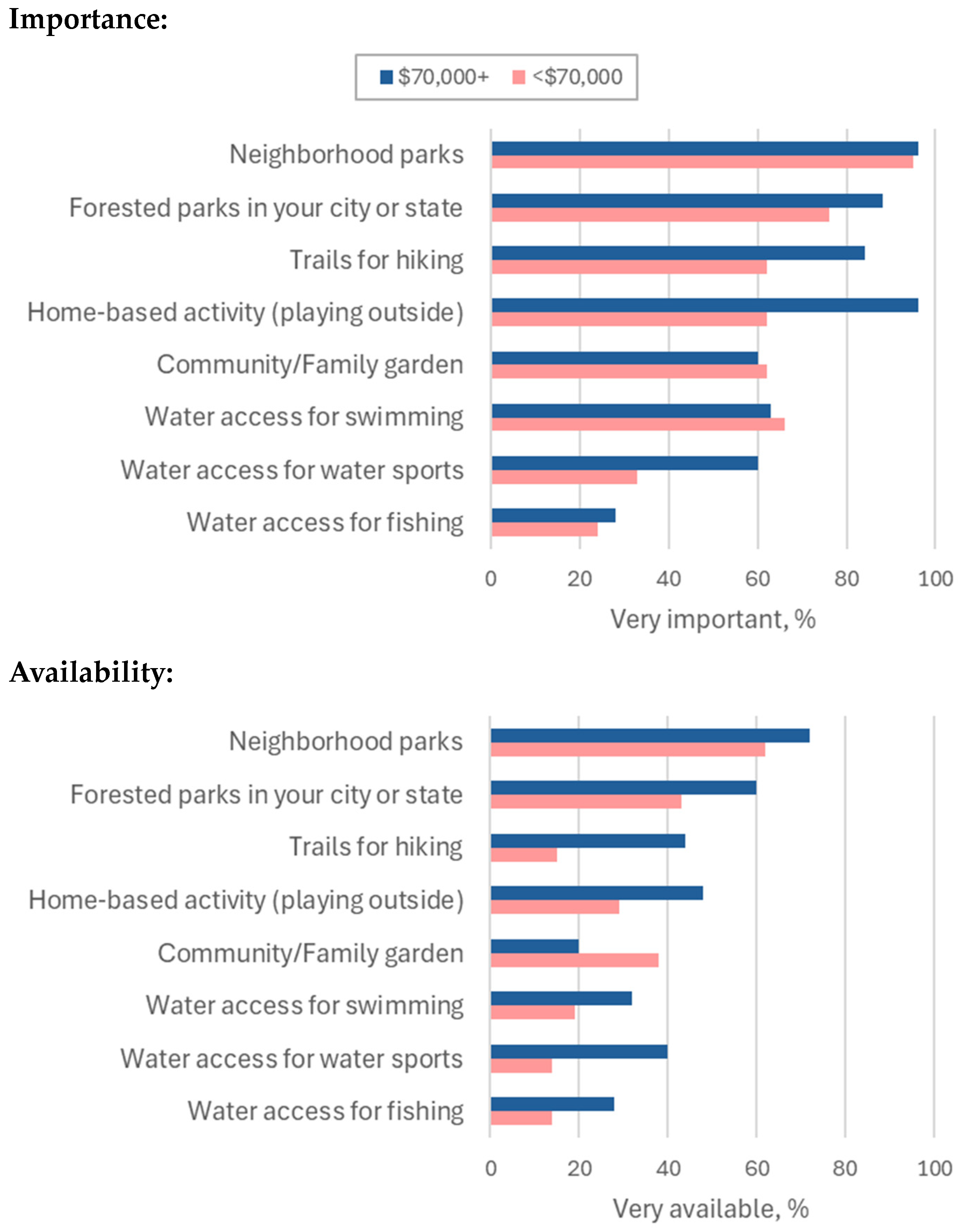

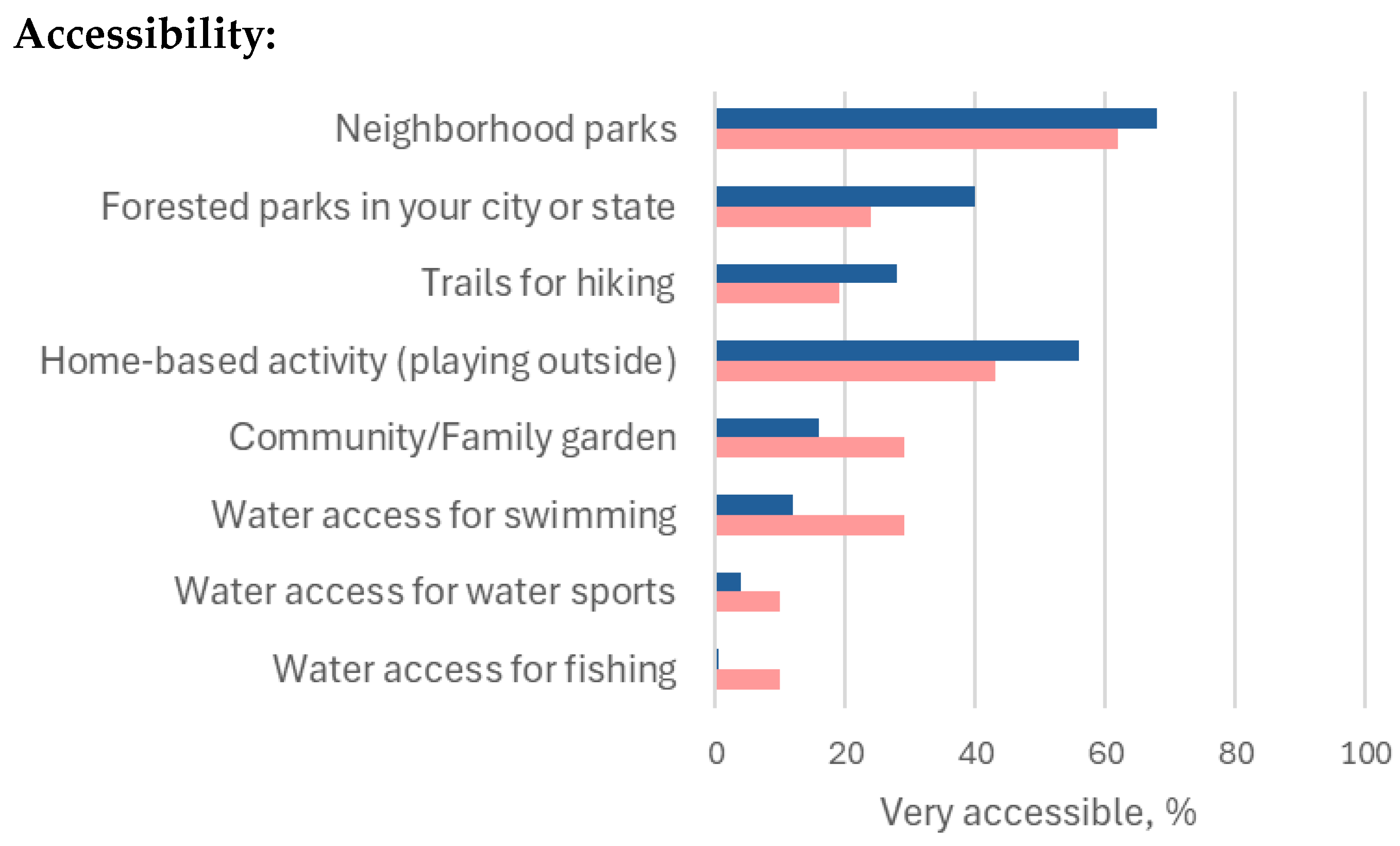

3.3. Outdoor Time Benefits, Barriers, and Importance, Availability, and Accessibility of Community Resources for Outdoor Time

4. Discussion

4.1. Outdoor Time and Physical and Mental Health Outcomes: Why Income Matters

4.2. Outdoor Time Benefits and Barriers and Importance, Availability, and Accessibility of Community Resources for Outdoor Time

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Hahn, K.S.; Daily, G.C.; Gross, J.J. Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8567–8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, G.; Daily, G.; Benjamin, J.; Gross, J. The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchley, R.A.; Strayer, D.L.; Atchley, P. Creativity in the Wild: Improving Creative Reasoning through Immersion in Natural Settings. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.J.J.; Tester, J.; Henderson, S.W. Environment Shapes Health, Including Children’s Mental Health. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.; Evans, G. Nearby Nature: A buffer of life stress among rural children. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E.; Taylor, A.F. A potential natural treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Evidence from a national study. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoly, E.; Dadvand, P.; Forns, J.; López-Vicente, M.; Basagaña, X.; Julvez, J.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Sunyer, J. Green and Blue Spaces and Behavioral Development in Barcelona Schoolchildren: The BREATHE Project. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balseviciene, B.; Sinkariova, L.; Grazuleviciene, R.; Andrusaityte, S.; Uzdanaviciute, I.; Dedele, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Impact of Residential Greenness on Preschool Children’s Emotional and Behavioral Problems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 6757–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevych, I.; Tiesler, C.M.T.; Fuertes, E.; Romanos, M.; Dadvand, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Berdel, D.; Koletzko, S.; Heinrich, J. Access to urban green spaces and behavioural problems in children: Results from the GINIplus and LISAplus studies. Environ. Int. 2014, 71, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, H.L.; Whitaker, R.C. Resurrecting free play in young children: Looking beyond fitness and fatness to attention, affiliation, and affect. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdette, H.L.; Whitaker, R.C.; Daniels, S.R. Parental report of outdoor playtime as a measure of physical activity in preschool-aged children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerwagen, J.; Orians, G. The Ecological World of Children. In Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 29–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.F.; Wilson, J.S.; Liu, G.C. Neighborhood greenness and 2-year changes in body mass index of children and youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadvand, P.; Villanueva, C.M.; Font-Ribera, L.; Martinez, D.; Basagaña, X.; Belmonte, J.; Vrijheid, M.; Gražulevičienė, R.; Kogevinas, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Risks and Benefits of Green Spaces for Children: A Cross-Sectional Study of Associations with Sedentary Behavior, Obesity, Asthma, and Allergy. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovasi, G.S.; Schwartz-Soicher, O.; Quinn, J.W.; Berger, D.K.; Neckerman, K.M.; Jaslow, R.; Lee, K.K.; Rundle, A. Neighborhood safety and green space as predictors of obesity among preschool children from low-income families in New York City. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Health of Parents and Their Children: A Two-Generation Inquiry—Child Trends—ChildTrends. Available online: https://www.childtrends.org/publications/the-health-of-parents-and-their-children-a-two-generation-inquiry (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Wolicki, S.B.; Bitsko, R.H.; Cree, R.A.; Danielson, M.L.; Ko, J.Y.; Warner, L.; Robinson, L.R. Mental Health of Parents and Primary Caregivers by Sex and Associated Child Health Indicators. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2021, 2, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppert Cordts, K.M.; Wilson, A.C.; Riley, A.R. More than Mental Health: Parent Physical Health and Early Childhood Behavior Problems. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, N. Long-term health effects of childhood parental income. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 317, 115607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A. Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 159, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Kim, L.E. Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 105, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, E.D.; Doan, S.; Woo, A.; Gittens, A.D.; Lawrence, R.A.; Berdie, L.; Wolfe, R.L.; Greer, L.; Schwartz, H.L. Restoring Teacher and Principal Well-Being Is an Essential Step for Rebuilding Schools: Findings from the State of the American Teacher and State of the American Principal Surveys; Rand Corporation: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L.; Meitner, M.J.; Girling, C.; Sheppard, S.R.J.; Lu, Y. Who has access to urban vegetation? A spatial analysis of distributional green equity in 10 US cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L.; Quinton, J. Invited perspective: Natureis unfairly distributed in the united states-but that’s only part of the global green equity story. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 011301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: An observational population study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klompmaker, J.O.; Hart, J.E.; Bailey, C.R.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Casey, J.A.; Hanley, J.R.; Minson, C.T.; Scott Ogletree, S.; Rigolon, A.; Laden, F.; et al. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in multiple measures of blue and green spaces in the United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiza-Pérez, M.; García-Baquero, G.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Riaño, I.; González, L.; Delgado-Saborit, J.M.; Guxens, M.; Fossati, S.; Vrijheid, M.; Fernandes, A.; et al. Social inequalities, green and blue spaces and mental health in 6–12 years old children participating in the INMA cohort. Health Place 2023, 83, 103104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ParkScore Home: Trust for Public Land. Available online: https://www.tpl.org/parkscore (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Dai, D. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in urban green space accessibility: Where to intervene? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 102, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Public Radio. Parks In Nonwhite Areas Are Half the Size of Ones in Majority-White Areas, Study Says. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2020/08/05/899356445/parks-in-nonwhite-areas-are-half-the-size-of-ones-in-majority-white-areas-study (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- The Heat Is On|The Trust for Public Land. Available online: https://www.tpl.org/the-heat-is-on (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Casey, J.A.; James, P.; Cushing, L.; Jesdale, B.M.; Morello-Frosch, R. Race, ethnicity, income concentration and 10-year change in urban greenness in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T. Green space, psychological restoration, and health inequality. Lancet 2008, 372, 1614–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.J.; Richardson, E.A.; Shortt, N.K.; Pearce, J.R. Neighborhood Environments and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Mental Well-Being. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, B.W.; Lovell, R.; Higgins, S.L.; White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Osborne, N.J.; Husk, K.; Sabel, C.E.; Depledge, M.H. Beyond greenspace: An ecological study of population general health and indicators of natural environment type and quality. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A. Could nature help children rise out of poverty? Green space and future earnings from a cohort in ten U.S. cities. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; McAnirlin, O.; Yoon, H. Green Space and Health Equity: A Systematic Review on the Potential of Green Space to Reduce Health Disparities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikorska, D.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Krauze, K.; Sikorski, P. The role of informal green spaces in reducing inequalities in urban green space availability to children and seniors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 108, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, M.; Brindley, P.; Jorgensen, A.; Maheswaran, R. Population-level linkages between urban greenspace and health inequality: The case for using multiple indicators of neighbourhood greenspace. Health Place 2020, 62, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Determinants of Health—Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Lopez, M.; Ruiz, M.O.; Rovnaghi, C.R.; Tam, G.K.Y.; Hiscox, J.; Gotlib, I.H.; Barr, D.A.; Carrion, V.G.; Anand, K.J.S. The social ecology of childhood and early life adversity. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Bhavnani, S.; Betancourt, T.S.; Tomlinson, M.; Patel, V. Adverse childhood experiences and lifelong health. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1639–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S.; Siegel, B.S.; Dobbins, M.I.; Earls, M.F.; McGuinn, L.; Pascoe, J.; Wood, D.L.; High, P.C.; Donoghue, E.; et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adversity in Early Childhood—Center for American Progress. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/adversity-early-childhood/ (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Blair, C.; Raver, C.C.; Granger, D.; Mills-Koonce, R.; Hibel, L. Allostasis and allostatic load in the context of poverty in early childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2011, 23, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pediatrics, Council on Community. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20160339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, J.M.; Wood, D.L.; Duffee, J.H.; Kuo, A. Mediators and adverse effects of child poverty in the United States. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20160340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, N.L.; Hanson, J.L.; Wolfe, B.L.; Pollak, S.D. Association of Child Poverty, Brain Development, and Academic Achievement. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiscella, K.; Kitzman, H. Disparities in academic achievement and health: The intersection of child education and health policy. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, J.W.; Loeb, S.; Chamberlain, L.J. The intersection of health and education to address school readiness of all children. Pediatrics 2018, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Public Health Association. Improving Health and Wellness Through Access to Nature. Available online: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/08/09/18/improving-health-and-wellness-through-access-to-nature (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Lee, A.C.K.; Jordan, H.C.; Horsley, J. Value of urban green spaces in promoting healthy living and wellbeing: Prospects for planning. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2015, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumanyika, S. Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention: A New Framework; NAM Perspectives: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust for America’s Health. State of Obesity 2024: Better Policies for a Healthier America. Available online: https://www.tfah.org/report-details/state-of-obesity-2024/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- National Institutes of Health. National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework. Available online: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework/nimhd-framework.html (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- National Institutes of Health. National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities Community-Based Participatory Research Program (CBPR). Available online: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/programs/extramural/community-based-participatory.html (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Fyfe-Johnson, A.L.; Hazlehurst, M.F.; Perrins, S.P.; Bratman, G.N.; Thomas, R.; Garrett, K.A.; Hafferty, K.R.; Cullaz, T.M.; Marcuse, E.K.; Tandon, P.S. Nature and children’s health: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2021, 148, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; Neal, L.O.; Mcleod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Duda, S.N.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.; Senn, S.J.; Rothman, K.J.; Carlin, J.B.; Poole, C.; Goodman, S.N.; Altman, D.G. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: A guide to misinterpretations. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 31, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stata. Statistical Software for Data Science. Available online: https://www.stata.com/ (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Richter, L.; Van Der Gaag, J.; Bhutta, Z.A. An integrated scientific framework for child survival and early childhood development. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e460–e472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.A.; Barnett, W.S.; Knopf, J.A.; Truman, B.I.; Johnson, R.L.; Fielding, J.E.; Muntaner, C.; Jones, C.P.; Fullilove, M.T.; Hunt, P.C.; et al. Early Childhood Education to Promote Health Equity. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2016, 22, E1–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for American Progress. The Nature Gap. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-nature-gap/ (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- North Carolina State University, College of Natural Resources. Nature Gap: Why Outdoor Spaces Lack Diversity and Inclusion. Available online: https://cnr.ncsu.edu/news/2020/12/outdoor-diversity-inclusion/ (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Sierra Club. Why People of Color Often Feel Unsafe in the Outdoors. Available online: https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/why-people-color-often-feel-unsafe-outdoors (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- The Atlantic. Five Ways to Make the Outdoors More Inclusive. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/rei-2018/five-ways-to-make-the-outdoors-more-inclusive/3019/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Syed, S.T.; Gerber, B.S.; Sharp, L.K. Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 976–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Jin, X.; Zhang, J. Equity in park green spaces: A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review from 2014-2023. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1374973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Institute. Changing the Story About Park and Green Space Equity: A Messaging Guide for Advocates. Available online: https://www.phi.org/thought-leadership/changing-the-story-about-park-and-green-space-equity-a-messaging-guide-for-advocates/ (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Vox. The American Outdoors Is Financially Inaccessible. Can it be More Equitable? Available online: https://www.vox.com/23894176/great-outdoors-exclusionary-nature-hiking-equity (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Network for Public Health Law. The Great American Outdoors Act: A Tool to Advance Public Health. Available online: https://www.networkforphl.org/news-insights/the-great-american-outdoors-act-a-tool-to-advance-public-health/ (accessed on 16 January 2025).

| Annual Household Income | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <USD 70,000 (n = 21) | USD 70,000+ (n = 25) | |||

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age, mean yrs (SD) | 30.6 | (6.6) | 36.2 | (4.7) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Racialized | 5 | (24%) | 6 | (25%) |

| Non-racialized | 16 | (76%) | 18 | (75%) |

| Hispanic, Mexican, or Latino/Latina ethnicity, n (%) | 3 | (14%) | 2 | (8%) |

| Sex assigned at birth, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 2 | (10%) | 1 | (4%) |

| Female | 19 | (90%) | 24 | (96%) |

| Gender identity, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 2 | (10%) | 1 | (4%) |

| Female | 16 | (76%) | 23 | (92%) |

| Transgender | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (4%) |

| Non-binary | 3 | (14%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Current employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Out of work | 1 | (5%) | 8 | (32%) |

| Unable to work | 1 | (5%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Employed | 19 | (90%) | 17 | (68%) |

| Completed education, n (%) | ||||

| High school/GED | 6 | (28%) | 1 | (4%) |

| Technical/vocational degree or Associate degree | 1 | (5%) | 1 | (4%) |

| College graduate (Bachelor’s degree) | 10 | (48%) | 9 | (36%) |

| Post-graduate degree or professional degree | 4 | (19%) | 14 | (56%) |

| Key stakeholder status, n (%) | ||||

| Outdoor educator | 16 | (76%) | 3 | (12%) |

| Caregiver | 5 | (24%) | 22 | (88%) |

| Physical and mental health | ||||

| Self-reported general health, n (%) | ||||

| Poor | 1 | (5%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Fair | 3 | (14%) | 2 | (8%) |

| Good | 8 | (38%) | 3 | (12%) |

| Very good | 6 | (29%) | 15 | (60%) |

| Excellent | 3 | (14%) | 5 | (20%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.9 | (10.6) | 25.5 | (6.0) |

| GAD-7 anxiety scale, mean (SD) | 7.3 | (5.3) | 5.6 | (4.3) |

| PHQ-8 depression scale, mean (SD) | 5.9 | (5.1) | 3.8 | (4.0) |

| Perceived stress scale, mean (SD) | 16.2 | (6.7) | 14.7 | (5.7) |

| Count of 11 adverse childhood experiences, mean (SD) | 2.3 | (1.6) | 1.4 | (1.3) |

| Count of 11 adverse childhood experiences, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 5 | (24%) | 7 | (28%) |

| 1 | 1 | (5%) | 7 | (28%) |

| 2 | 5 | (24%) | 6 | (24%) |

| 3 | 5 | (24%) | 3 | (12%) |

| 4 | 3 | (14%) | 2 | (8%) |

| 5 | 2 | (9%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Brief resilience scale, mean (SD) | 3.2 | (0.7) | 3.4 | (0.7) |

| Sedentary time (hours/day), n (%) | ||||

| 1 h or less | 0 | (0%) | 3 | (12%) |

| 2–4 h | 12 | (57%) | 16 | (64%) |

| 5–7 h | 8 | (38%) | 5 | (20%) |

| 8–9 h | 1 | (5%) | 1 | (4%) |

| Sleep (hours/night), n (%) | ||||

| 4–7 h | 8 | (38%) | 12 | (48%) |

| 8 h | 11 | (52%) | 13 | (52%) |

| 9 h or more | 2 | (10%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Prediabetes, n (%) | 2 | (10%) | 2 | (8%) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (4%) |

| High blood pressure, n (%) | 2 | (10%) | 2 | (8%) |

| Current smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Not at all | 20 | (95%) | 25 | (100%) |

| Every day | 1 | (5%) | 0 | (0%) |

| Outdoor time/week, median minutes (min, max) | 1860 | (0, 2700) | 480 | (135, 2880) |

| Health Construct | Crude Diff 1 (95% CI) | Adjusted 2 Diff 1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Very good or excellent self-reported health, % | −13% (−41%, 14%) | −4% (−37%, 30%) |

| Body mass index, mean kg/m2 | −4.9 (−9.9, 0.1) | −5.5 (−11.6, 0.7) |

| GAD-7 anxiety, mean score | −0.2 (−3.1, 2.7) | −1.7 (−5.4, 2.1) |

| PHQ-8 depression, mean score | −0.4 (−3.2, 2.4) | −0.9 (−4.3, 2.5) |

| Perceived stress scale, mean score | −0.7 (−4.4, 3.0) | −1.1 (−5.9, 3.7) |

| Brief resilience scale, mean score | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.3) | 0.0 (−0.6, 0.5) |

| Health construct | Crude Diff 1 (95% CI) | Model 2 2 Diff 1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Very good or excellent self-reported health, % | 37% (11%, 63%) | 41% (12%, 70%) |

| Body mass index, mean kg/m2 | −2.4 (−7.5, 2.7) | −5.5 (−11.0, −0.0) |

| GAD-7 anxiety, mean score | −1.8 (−4.7, 1.1) | −1.2 (−4.6, 2.3) |

| PHQ-8 depression, mean score | −2.1 (−4.8, 0.7) | −2.5 (−5.5, 0.5) |

| Perceived stress scale, mean score | −1.5 (−5.2, 2.2) | −1.8 (−6.0, 2.5) |

| Brief resilience scale, mean score | 0.2 (−0.3, 0.6) | 0.0 (−0.5, 0.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fyfe-Johnson, A.L.; Noonan, C.J.; Butcher, M.B.; Haakenstad, M.K. Physical and Mental Health of Caregivers and Educators of Preschool-Aged Children: Identifying Benefits and Barriers to Outdoor Time, How Outdoor Time Can Make a Difference for Health Equity, and Why Income Matters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020236

Fyfe-Johnson AL, Noonan CJ, Butcher MB, Haakenstad MK. Physical and Mental Health of Caregivers and Educators of Preschool-Aged Children: Identifying Benefits and Barriers to Outdoor Time, How Outdoor Time Can Make a Difference for Health Equity, and Why Income Matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020236

Chicago/Turabian StyleFyfe-Johnson, Amber L., Carolyn J. Noonan, Maria B. Butcher, and Magdalena K. Haakenstad. 2025. "Physical and Mental Health of Caregivers and Educators of Preschool-Aged Children: Identifying Benefits and Barriers to Outdoor Time, How Outdoor Time Can Make a Difference for Health Equity, and Why Income Matters" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020236

APA StyleFyfe-Johnson, A. L., Noonan, C. J., Butcher, M. B., & Haakenstad, M. K. (2025). Physical and Mental Health of Caregivers and Educators of Preschool-Aged Children: Identifying Benefits and Barriers to Outdoor Time, How Outdoor Time Can Make a Difference for Health Equity, and Why Income Matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020236