Factors That Influence Maternal Child Health Nurses’ Identification of Risk of Family Violence to First Nations Women in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims

2.2. Research Questions

2.3. Design

2.4. Setting

2.5. Sample/Participants

2.5.1. Maternal and Child Health Nurses

2.5.2. First Nations Women with Children Aged Zero to Five Years

2.6. Data Collection

2.6.1. Maternal and Child Health Nurses

2.6.2. First Nations Women with Children Aged Zero to Five Years

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Validity and Reliability/Rigour

3. Results

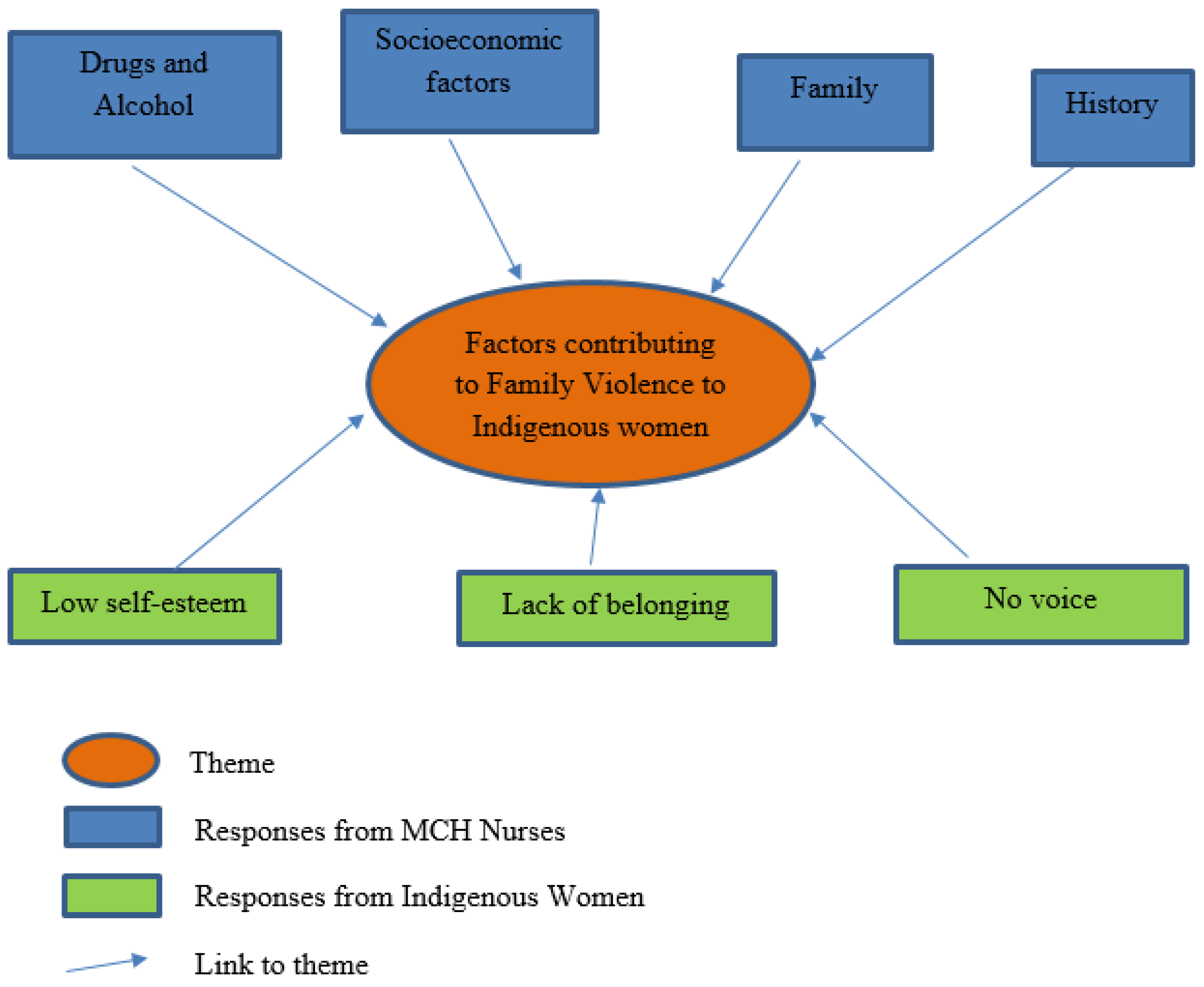

3.1. Factors Contributing to Family Violence to First Nations Women with Children Aged Zero to Five Years

3.2. Factors That Contribute to Low Reporting of Family Violence by First Nations Women with Children Aged Zero to Five Years

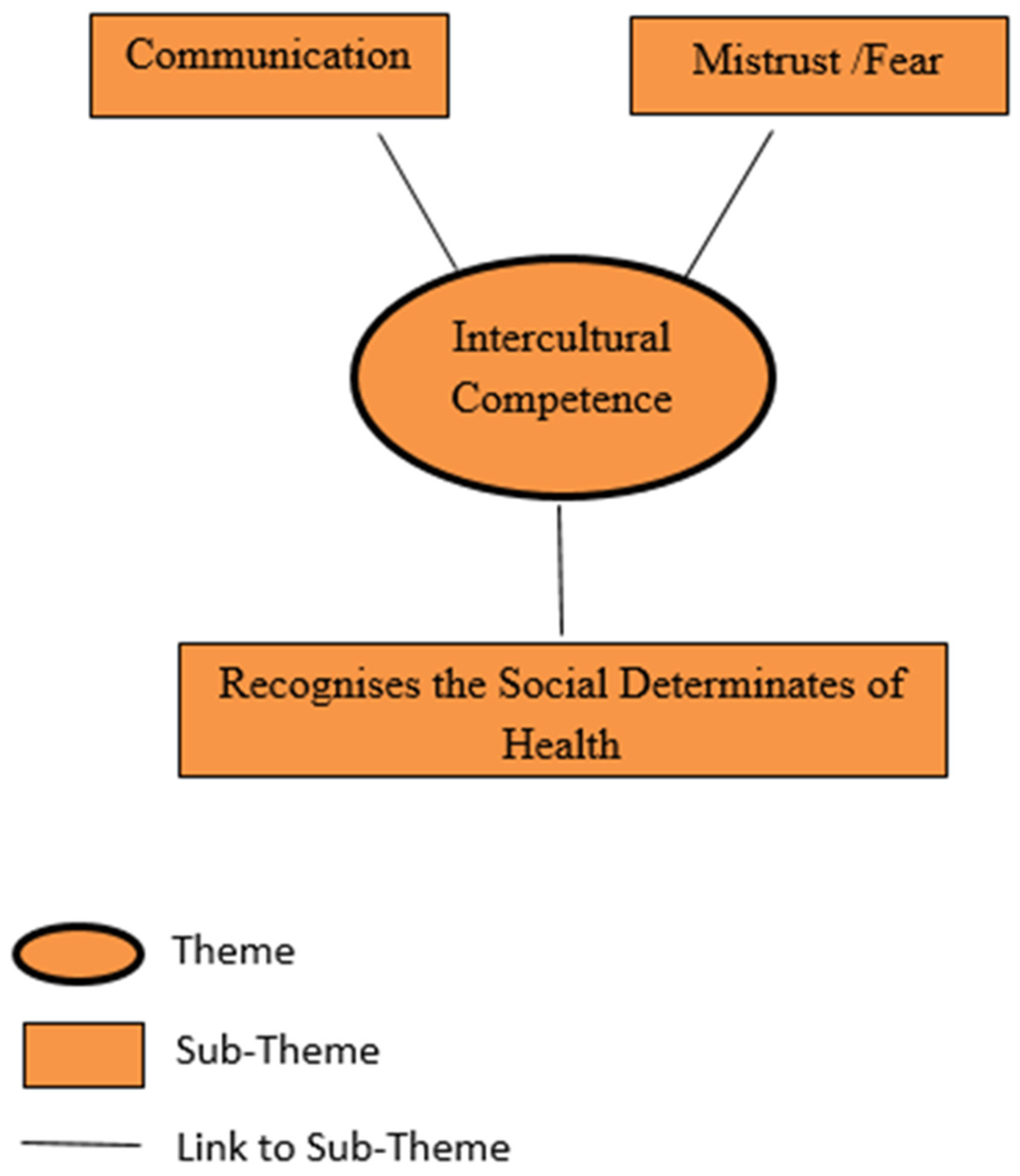

3.3. Factors That Influence Maternal Child Health Nurses’ Identification of Risk of Family Violence to First Nations Women with Children Aged Zero to Five Years

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). General Comment No. 15 (2013) on the Right of the Child to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 24), 17 April 2013, CRC/C/GC/15. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/51ef9e134.html (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Anderson, I.; Robson, B.; Connolly, M.; Al-Yaman, F.; Bjertness, E.; King, A.; Tynan, M.; Madden, R.; Bang, A.; Coimbra, C.E.; et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet-Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): A population study. Lancet 2016, 388, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smylie, J.; Adomako, P. Indigenous Children’s Health Report; Centre for Research on Inner City Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund; World Bank Group. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development: A Framework for Helping Children Survive and Thrive to Transform Health and Human Potential; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Auditor-General’s Office [VAGO]. Victorian Auditor-General’s Office Annual Report. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Belli, P.C.; Bustreo, F.; Preker, A. Investing in children’s health: What are the economic benefits? Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sweeny, K. The Influence of Childhood Circumstances on Adult Health. Report to the Mitchell Institute for Health and Education Policy. Victoria Institute of Strategic. Economic Studies. Contract No.: Commissioned Report, 01/2014. Victoria University. 2014. Available online: https://www.vu.edu.au/mitchell-institute/prevention-risk/the-influence-of-childhood-circumstances-on-adult-health (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Shonkoff, J.; Phillips, D. From Neurons to Neighbourhoods: The Science of Early Child Development; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Boyce, W.T.; McEwen, B.S. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA 2009, 301, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yelland, J.; Weetra, D.; Stuart-Butler, D.; Deverix, J.; Leane, C.; Ah Kit, J.; Glover, K.; Gartland, D.; Newbury, J.; Brown, S. Primary health care for Aboriginal women and children in the year after birth: Findings from a population-based study in South Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2016, 40, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, E.; Davis, E.; Gibbs, L.; Block, K.; Szwarc, J.; Casey, S.; Duell-Piening, P.; Waters, E. Accessing maternal and child health services in Melbourne, Australia: Reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, V.; Walter, A.; Guan, J.; Descallar, J.; Axelsson, E.; Einfeld, S.; Eastwood, J.; Murphy, E.; Beasley, D.; Silove, N.; et al. Maternal help-seeking for child development concerns: Associations with socio-demographic factors. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.; Luxford, Y. Yaitya Tirka Madlanna Warratinna: Exploring what sexual health nurses need to know and do in order to meet the sexual health needs of young Aboriginal women in Adelaide. Collegian 2007, 14, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboriginal. In Merriam-Webster.com. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/aboriginal (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- State of Victoria. Royal Commission into Family Violence: Summary and Recommendations. From Parl Paper No. 132 (2014–16). Available online: https://australianwomenshealth.org/resource/royal-commission-into-family-violence-summary-and-recommendations/#:~:text=This%20state-based%20report%20summarises%20findings%20from%20the%20Victorian,to%20prevent%20family%20violence%2C%20support%20victims%20and%20more (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census Community Profiles. 2016. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/community-profiles/2016/0 (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry [PVVCI]. Available online: http://childprotectioninquiry.archive.vic.gov.au/report-pvvc-inquiry.html (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Marrone, S. Understanding barriers to health care: A review of disparities in health care services among Indigenous populations. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2007, 66, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbold, A.R.; Bailie, R.S.; Si, D.; Dowden, M.C.; Kennedy, C.M.; Cox, R.J.; O’Donoghue, L.; Liddle, H.E.; Kwedza, R.K.; Thompson, S.C.; et al. Delivery of maternal health care in Indigenous primary care services: Baseline data for an ongoing quality improvement initiative. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Report on Violence and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Makkai, T.; Mouzos, J. Women’s Experiences of Male Violence: Findings from the Australian Component of the International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS); Australian Institute of Criminology: Canberra, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, P. Violence against Women in Australia: Additional Analysis of the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Personal Safety Survey; Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety: Sydney, Australia, 2012; Available online: http://anrows.org.au/publications/horizons/PSS (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Victoria’s Family Violence Protection Act. Available online: https://content.legislation.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/08-52aa053%20authorised_0.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- VicHealth. The Health Costs of Violence: Measuring the Burden of Disease Caused by Intimate Partner Violence: A Summary of Findings; Victorian Health Promotion Foundation: Carlton, Australia, 2004.

- Lievore, D. Non-Reporting and Hidden Recording of Sexual Assault: An International Literature Review; Australian Institute of Criminology: Canberra, Australia, 2003. Available online: https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/archive/archive-135 (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Department of Education and Training. [DET] Maternal and Child Health Services Annual Report 2017–2018. Melbourne. Available online: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/maternal-child-health/maternal-child-and-health-reporting-and-data (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Smith, J. The impact of intimate partner violence on children. In Intimate Partner Violence and Health Professionals; Roberts, G., Hegarty, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann, K.M.; Gaylord, N.K.; Holt, A.R.; Kenny, E.D. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.; Gee, G.; Harfield, S.; Campbell, S.; Brennan, S.; Clark, Y.; Mensah, F.; Arabena, K.; Herrman, H.; Brown, S.; et al. Parenting after a history of childhood maltreatment: A scoping review and map of evidence in the perinatal period. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, G.L.; Stacks, A.M. Developmental effects of exposure to intimate partner violence in early childhood: A review of the literature. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2009, 31, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Child Health Screening and Surveillance: A Critical Review of the Evidence; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Taft, A.J.; Hooker, L.; Humphreys, C.; Hegarty, K.; Walter, R.; Adams, C.; Agius, P.; Small, R. Maternal and child health nurse screening and care for mothers experiencing domestic violence (MOVE): A cluster randomised trial. BMC Med. 2025, 13, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlpine, L. Why might you use narrative methodology? A story about narrative. Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri. Est. J. Educ. 2016, 4, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, M. Anthropological Texts and Indigenous Standpoints. Aust. Aborig. Stud. 1998, 2, 3–12. Available online: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=151991702568013;res=IELAPA (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- West, R.; Stewart, L.; Foster, K.; Usher, K. Through a critical lens: Indigenist research and the Dadirri method. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronach, M.; Adair, D. Dadirri: Reflections on a research methodology used to build trust between a non-indigenous researcher and indigenous participants. Cosmopolitan. Civ. Soc. J. 2014, 6, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.; Hamilton, B.; Humphreys, C. A Global Silence: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis of Aboriginal Mothering Through Domestic and Family Violence. Affil. Fem. Inq. Soc. Work. 2021, 37, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelto, P.; Pelto, G. Anthropological Research: The Structure of Inquiry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S. Qualitative analysis at the interface of Indigenous and Western knowledge systems: The Herringbone stitch model. Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 939–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mob. In Merriam-Webster.com. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mob (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Morse, J.M. Determining sample size. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. The significance of saturation. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L. Promoting interpersonal and intercultural communication with Flipgrid: Design, implementation, and outcomes. In New Technological Applications for Foreign and Second Language Learning and Teaching; Kruk, M., Peterson, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiolet, R.; Tarzia, L.; Owen, R.; Eccles, C.; Nicholson, K.; Owen, M.; Fry, S.; Knox, J.; Hegarty, K. Indigenous perspectives on help-seeking for family violence: Voices from an Australian community. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 10128–10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milroy, H.; Dudgeon, P.; Walker, R. Community life and development programs—Pathways to healing. In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; Duggeon, P., Milroy, H., Walker, R., Eds.; Australian Government Department of Health & Ageing: Canberra, Australia, 2014. Available online: http://aboriginal.telethonkids.org.au/kulunga-research-network/working-together-2nd-edition-%281%29/ (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Turley, J.; Vanek, J.; Johnston, S.; Archibald, D. Nursing role in well-childcare: Systematic review of the literature. Can. Fam. Physician Med. De Fam. Can. 2018, 64, e169–e180. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Implementation Plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Austin, C.; Hills, D.; Cruickshank, M. Models and Interventions to Promote and Support Engagement of First Nations Women with Maternal and Child Health Services: An Integrative Literature Review. Children 2022, 9, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.; Arabena, K. Improving the engagement of Aboriginal families with maternal and child health services: A new model of care. Public Health Res. Pract. 2021, 31, 30232009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acil Allen Consulting. Aboriginal Families’ Perceptions of Maternal & Child Health: Consultation Report; Acil Allen Consulting: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organization. Aboriginal Families’ Engagement in Maternal and Child Health Services; Phase One: Project Report; Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organization: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Maternal and Child Health Service Guidelines 2011. Available online: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1599995339 (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Denzin, N.; Lincoln, Y. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Austin, C.L. Factors That Influence Maternal Child Health Nurses’ Identification of Risk of Family Violence to First Nations Women in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020217

Austin CL. Factors That Influence Maternal Child Health Nurses’ Identification of Risk of Family Violence to First Nations Women in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020217

Chicago/Turabian StyleAustin, Catherine Louise. 2025. "Factors That Influence Maternal Child Health Nurses’ Identification of Risk of Family Violence to First Nations Women in Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020217

APA StyleAustin, C. L. (2025). Factors That Influence Maternal Child Health Nurses’ Identification of Risk of Family Violence to First Nations Women in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020217