Formative Research for Adapting the Cholera-Hospital-Based-Intervention-for-7-Days (CHoBI7) Water Treatment and Hygiene Mobile Health Program for Scalable Delivery in Rural Bangladesh

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Overview

2.2. Study Eligibility Criteria and Enrollment Activities

2.3. CHoBI7 mHealth Scale-Up Program Delivery

2.4. Pilot Quantitative Data Collection Methods

2.5. Pilot Qualitative Data Collection Methods

2.6. Intervention Planning Workshops

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. CHoBI7 Program Adaptations for Scalable Delivery in a Rural Setting

3.1.1. Initial Development of Modified Healthcare Facility CHoBI7 WASH Module (Flipbook)

3.1.2. Videos on WASH Behaviors

3.1.3. Demonstrations of Handwashing Station Designs

“I was not taught how to put a faucet [tap] on a bottle, I made it myself… [I] made it with a 5 L oil bottle... If you want to buy a bucket, you have to go to the market, it will cost money... So, I had this idea [adding a tap on a bottle]… I made [the handwashing station] with what I have at home.”(SSI, Female)

3.1.4. Introduction of a New Design of a Handwashing Station on a Tubewell

“My baby throws this water [from the handwashing station] all day long. Because of this problem, I put [the bucket with tap handwashing station] away for a few days. I didn’t add water for a few days.”(FGD, Female)

“We did not make the bucket [“bucket with tap” handwashing station] but we have a bucket beside the tubewell. We keep water, keep soap [there]. And you are talking about making the bucket [handwashing station]; people’s financial situation is not always the same.”(SSI, Male)

3.1.5. Introduction of a New Handwashing Station Design Using a Plastic Bottle with a Hole

“In front of the toilet, we could make a hole in a bottle, along with a soapy water bottle, and hang them on a tree with a rope, placing something underneath it [for use as a basin]. That’s all [for the handwashing station].”(SSI, Male)

3.1.6. WASH Module (Flipbook) Page on Dos and Don’ts of Preparing a Handwashing Station

“When making [the hole in the bucket], [the rod] is heated in the stove to pierce a hole in it [to fix the tap]. Making the hole is a bit tricky because the rod [iron] is very hot. [The hole] has to be the right size; if it [the rod] is too hot, the hole will end up being too big.”(SSI, Female)

“I saw this [WASH module, flipbook] and I made that basin out of a bucket [“bucket with tap” handwashing station]…I had a broken bucket…I got the glue from the market…and a tap…I attached it [the broken parts of the bucket] with glue, then a cut a hole in one place using scissors [to fix the tap]. That’s how I made it…It was an old bucket, I wouldn’t have used it, [I] would have thrown it away… Later, I thought that instead of throwing it away, I should do this [make the handwashing station].”(SSI, Male)

3.1.7. Modified CHoBI7 Scale-Up Program mHealth Component

Assalamulalaikum. This is Dr. Chobi from the hospital. I am calling to remind you to make sure you and your family always wash your hands with soap before eating, feeding your children, and preparing your food, and after using your toilet or cleaning your child’s feces. Use your handwashing station you constructed to help with this. Help young children to wash their hands with soap. Perform these behaviors to keep your family safe from any more severe diarrhea! Share the message with your family!

3.1.8. Mobile Message Emphasizing Preparing a Handwashing Station During 7-Day High-Risk Period

“I bought the tap and kept it…but I still haven’t made it [fixed the tap to the bucket]… In my opinion, [not making the handwashing station] is just laziness, not because of money, more laziness.”(FGD, Female)

3.1.9. Changing Timing of mHealth Message Delivery

“If the phone calls are made after work, I can hear the thing [message] myself and…with the loudspeaker, I can play it for my family or neighbors. If I listen to it by myself, I might not remember everything… And [if I played Dr. Chobi’s call directly to everyone through the loudspeaker], then everyone could hear, everyone could understand.”(SSI, Male)

“[We have] two mobiles [phones] but one number is given [to the CHoBI7 program]. But we have never received [text] messages…but the phone [calls] came.”(SSI, Female)

3.1.10. Direct Mobile Phone Call by Health Promoters During 7-Day High-Risk Period

“No, I was not [at the healthcare facility]. If you explain [how to make a handwashing station] again now, I will make it.”(SSI, Male)

“When I heard [about making the handwashing station], the next day I made it [“bucket with tap” handwashing station]. From where I got the training, I was sent pictures and videos via WhatsApp.”(SSI, Male)

3.1.11. Cue Card and Mobile Messages on Chlorine Tablet Dosing Instructions

“Initially, I was confused about whether to add one or two [chlorine] tablets, [and] how many liters of water.”(SSI, Female)

“[My husband] set the pictures [cue cards and stickers] in such a way that as soon as I put the water jug in that place, I see that I need to add the tablet. That’s how I remember.”(SSI, Female)

3.1.12. Mobile Messages Emphasizing That Iron Filters Do Not Remove Germs

“Before, I had a clay/mud-made filter [to filter out iron]. I made this filter with sand, pieces of bricks, and cloth at the bottom in the pot, then making holes. By filtering this way, water becomes germ-free. The water becomes clean.”(SSI, Female)

“[This] filter is made by hand with sand and clay. [With this filter], then there is less iron [in the water]. It is not safe… It is not germ-free; germs are definitely there. To make it germ-free one must add [chlorine] tablets to the water.”(SSI, Female)

3.1.13. Mobile Messages Emphasizing That Chlorine Tablets Should Be Used Beyond the 7-Day High-Risk Period

“The rest of the tablets [chlorine] have been kept, my family [wife] can confirm this …Everyone in the family has recovered from that [diarrheal disease], so, they were no longer needed. Based on that, she [his wife] kept some, I think, few of the tablets have been kept.”(SSI, Male)

“[They] gave us medicine [chlorine tablets]. We took the medicine by adding [the tablets] to water in the way we were told [as part of the intervention]. We benefitted from this but could not finish all [of the tablets]. [The tablets] worked well after taking some of them… we were cured by taking some of them. Since we recovered, we don’t need to take them anymore.”(SSI, Male)

3.1.14. WASH Module (Flipbook) Clarifying That Arsenic- and Iron-Free Water Can Still Have Germs That Cause Diarrhea

“We drink [water] with [chlorine] tablets, even so [without adding the tablets] we drink it directly from it [tubewell]. Our tubewell water has no arsenic, even no iron, [it is] very fresh.”(SSI, Male)

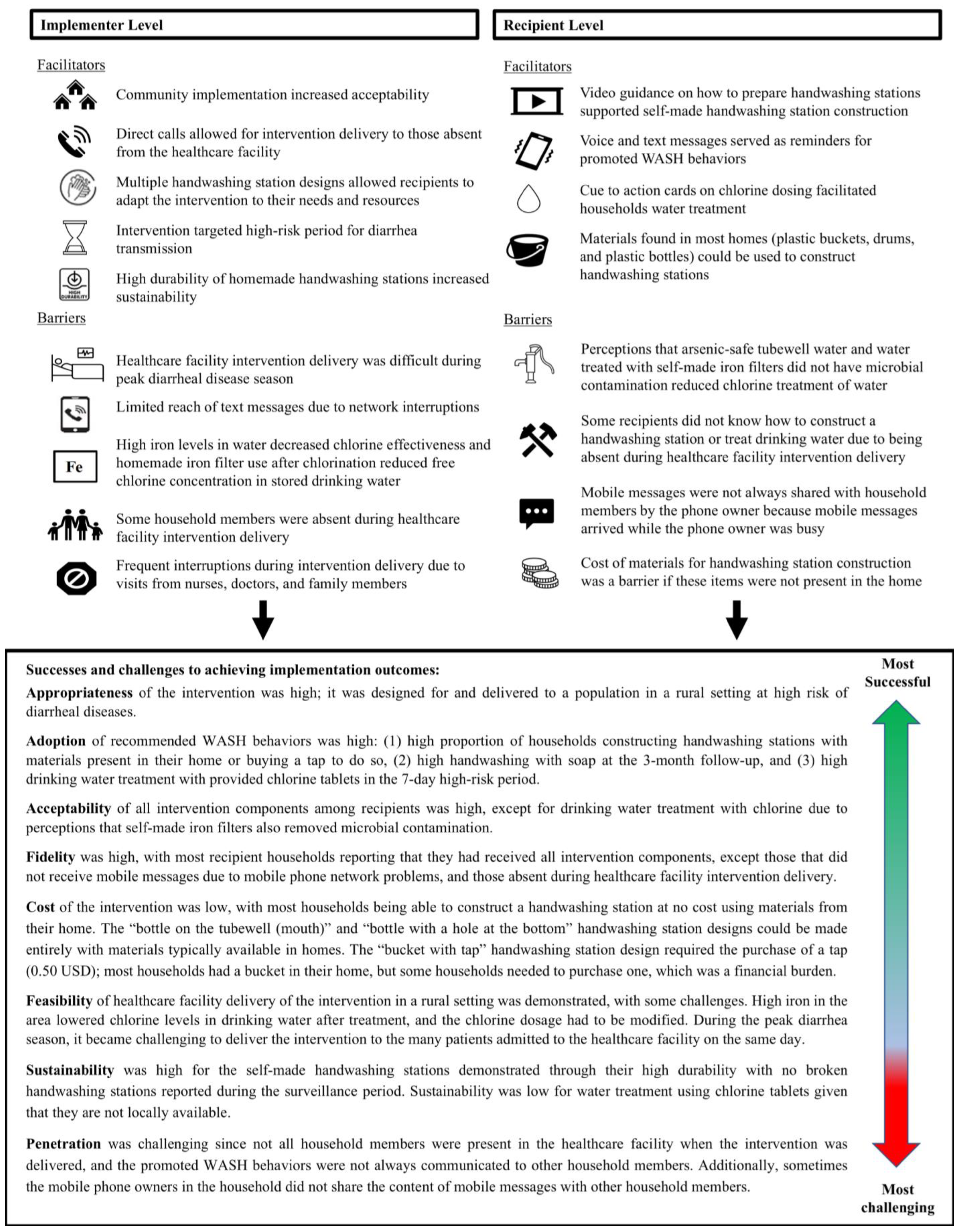

3.2. Implementation Outcomes

3.2.1. Recipient-Level Implementation Outcomes

3.2.2. Implementer Level Implementation Outcomes

“Their handwashing habit is satisfactory, but they don’t have any habit to boil their drinking water… As they have a lot of iron in the village area of Manikganj, they use a local filter [to remove iron]…and their idea is that water is safe as long as it is arsenic-free, and the local iron filter is used to remove the iron.”(Female Health Promoter)

“The doctor is visiting, we have to stop then and take a break. The nurse is coming, we have to take a break here, too. Or the patient’s household members are coming and have to take a break here.”(Female Health Promoter)

“The highest number of participants we are getting from each family is up to 1 or 2 members [for the healthcare facility based intervention]. If we are very lucky, we get three people but we don’t get more than that. …Especially the head of the family, we don’t get him [during the healthcare facility intervention delivery].”(Female Health Promoter)

“When they [recipients] first received the chlorine [tablets], they thought that they could buy it from the shop or pharmacy. But it is not available in the market. We have to ensure this [chlorine tablet availability]—that if they want to buy it, they can. If we are able to ensure this [chlorine tablet availability], then we can sustain it. Otherwise, they will drink the tubewell water directly. They will not boil their water. This is something we should pay attention to.”(Female Health Promoter)

“I think we have to work together along with the doctors and nurses. If we work together it would be more effective…We have to provide training to doctors and nurses, and we also need to work together; then, it would be good. When a doctor or nurse visits a patient during rounds, then they can also discuss this matter [the CHoBI7 program]; this would be beneficial.”(Female Implementer)

3.3. Quantitative Pilot Study Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheets; The Top 10 Causes of Death. December. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Fewtrell, L.; Kaufmann, R.B.; Kay, D.; Enanoria, W.; Haller, L.; Colford, J.M., Jr. Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clasen, T.; Schmidt, W.-P.; Rabie, T.; Roberts, I.; Cairncross, S. Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007, 334, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejemot-Nwadiaro, R.I.; Ehiri, J.E.; Meremikwu, M.M.; Critchley, J.A. Hand washing for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Libr. 2008, 1, CD004265. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, N.A.; Hulland, K.R.S.; Dreibelbis, R.; Sultana, F.; Winch, P.J. Sustained adoption of water, sanitation and hygiene interventions: Systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2018, 23, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luby, S.P.; Agboatwalla, M.; Bowen, A.; Kenah, E.; Sharker, Y.; Hoekstra, R.M. Difficulties in maintaining improved handwashing behavior, Karachi, Pakistan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 81, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.M.; Zohura, F.; Teman, A.; Thomas, E.; Hasan, T.; Rana, S.; Parvin, T.; Sack, D.A.; Bhuyian, S.I.; Labrique, A.; et al. Formative research for the design of a scalable water, sanitation, and hygiene mobile health program: CHoBI7 mobile health program. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1028. [Google Scholar]

- Burrowes, V.; Perin, J.; Monira, S.; Sack, D.A.; Rashid, M.U.; Mahamud, T.; Rahman, Z.; Mustafiz, M.; Bhuyian, S.I.; Begum, F.; et al. Risk Factors for Household Transmission of Vibrio cholerae in Dhaka, Bangladesh (CHoBI7 Trial). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.M.; Hasan, K.; Monira, S.; Rahman, Z.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M.; Rashid, M.U.; Zohura, F.; Parvin, T.; Islam Bhuyian, M.S.; Mahmud, M.T.; et al. A prospective cohort study comparing household contact and water Vibrio cholerae isolates in households of cholera patients in rural Bangladesh. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, A.A.; Khan, A.I.; Chowdhury, F.; LaRocque, R.C.; Faruque, A.S.; Ryan, E.T.; Calderwood, S.B.; Qadri, F.; Harris, J.B. Clinical outcomes in household contacts of patients with cholera in Bangladesh. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Diarrhoeal Disease. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- George, C.M.; Monira, S.; Sack, D.A.; Rashid, M.U.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M.; Mahmud, T.; Rahman, Z.; Mustafiz, M.; Bhuyian, S.I.; Winch, P.J.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Hospital-Based Hygiene and Water Treatment Intervention (CHoBI7) to Reduce Cholera. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.D.; Zohura, F.; Hasan, M.T.; Rana, M.S.; Teman, A.; Parvin, T.; Masud, J.; Bhuyian, M.S.; Hossain, M.K.; Hasan, M.; et al. Formative research to scale up a handwashing with soap and water treatment intervention for household members of diarrhea patients in health facilities in Dhaka, Bangladesh (CHoBI7 program). BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurovac, D.; Sudoi, R.K.; Akhwale, W.S.; Ndiritu, M.; Hamer, D.H.; Rowe, A.K.; Snow, R.W. The effect of mobile phone text-message reminders on Kenyan health workers’ adherence to malaria treatment guidelines: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole-Lewis, H.; Kershaw, T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol. Rev. 2010, 32, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Free, C.; Phillips, G.; Galli, L.; Watson, L.; Felix, L.; Edwards, P.; Patel, V.; Haines, A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, E.S.; Goldberg, A.B.; Labrique, A.B.; Cook, S.H.; Schmid, C.; Cole, C.F.; Obregón, R.A. Understanding the role of mHealth and other media interventions for behavior change to enhance child survival and development in low- and middle-income countries: An evidence review. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19 (Suppl. S1), 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.M.; Monira, S.; Zohura, F.; Thomas, E.D.; Hasan, M.T.; Parvin, T.; Hasan, K.; Rashid, M.U.; Papri, N.; Islam, A.; et al. Effects of a Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Mobile Health Program on Diarrhea and Child Growth in Bangladesh: A Cluster-randomized Controlled Trial of the Cholera Hospital-based Intervention for 7 Days (CHoBI7) Mobile Health Program. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e2560-e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engagespark. Available online: https://www.engagespark.com/ (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- George, C.M.; Jung, D.S.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M.; Monira, S.; Sack, D.A.; Rashid, M.U.; Mahmud, M.T.; Mustafiz, M.; Rahman, Z.; Bhuyian, S.I.; et al. Sustained Uptake of a Hospital-Based Handwashing with Soap and Water Treatment Intervention (Cholera-Hospital-Based Intervention for 7 Days [CHoBI7]): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Safe Water System. Free Chlorine Testing. Available online: http://medbox.iiab.me/modules/en-cdc/www.cdc.gov/safewater/chlorine-residual-testing.html (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreibelbis, R.; Winch, P.J.; Leontsini, E.; Hulland, K.R.; Ram, P.K.; Unicomb, L.; Luby, S.P. The Integrated Behavioural Model for Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: A systematic review of behavioural models and a framework for designing and evaluating behaviour change interventions in infrastructure-restricted settings. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.M.; Higgins, E.M.; Arman, S.; Ercumen, A.; Ashraf, S.; Das, K.K.; Rahman, M.; Luby, S.P.; Unicomb, L. Effect of Groundwater Iron on Residual Chlorine in Water Treated with Sodium Dichloroisocyanurate Tablets in Rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, S.K.; Thomas, E.D.; Masud, J.; Zohura, F.; Hasan, T.; Parvin, T.; Bhuyian, M.S.; Minhaj, M.I.; Johura, F.; Sultana, M.; et al. Formative Research for the Design of a Baby Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Mobile Health Program in Bangladesh (CHoBI7 Mobile Health Program). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, C.M.; Parvin, T.; Bhuyian, M.S.I.; Uddin, I.M.; Zohura, F.; Masud, J.; Monira, S.; Sack, D.A.; Perin, J.; Alam, M.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of the Cholera-Hospital-Based-Intervention-for-7-Days (CHoBI7) Cholera Rapid Response Program to Reduce Diarrheal Diseases in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Mello-Guyett, L.; Cumming, O.; Bonneville, S.; D’hondt, R.; Mashako, M.; Nakoka, B.; Gorski, A.; Verheyen, D.; Van den Bergh, R.; Welo, P.O.; et al. Effectiveness of hygiene kit distribution to reduce cholera transmission in Kasaï-Oriental, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2018: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.M.; Sanvura, P.; Bisimwa, J.-C.; Endres, K.; Namunesha, A.; Felicien, W.; Banywesize, B.M.; Williams, C.; Perin, J.; Sack, D.A.; et al. Effects of a Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Program on Diarrhea and Child Growth in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial of the Preventative-Intervention-for-Cholera-for-7-Days (PICHA7) Program. medRxiv 2024. medRxiv:2024.12.16.24318942. [Google Scholar]

- Islam Bhuyian, M.S.; Saxton, R.; Hasan, K.; Masud, J.; Zohura, F.; Monira, S.; Kumar Biswas, S.; Tasdik Hasan, M.; Parvin, T.; Minhaj, I.; et al. Process evaluation for the delivery of a water, sanitation and hygiene mobile health program: Findings from the randomised controlled trial of the CHoBI7 mobile health program. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2020, 25, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Baseline Demographics | Intervention Arm | Standard Message Arm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | N | % | n | N | |

| Participants enrolled | 219 | 56 | ||||

| Children < 5 years of age | 28% | 62 | 219 | 29% | 16 | 56 |

| Child caregivers | 44% | 97 | 219 | 38% | 21 | 56 |

| Female | 57% | 125 | 219 | 63% | 35 | 56 |

| Households | 49 | 15 | ||||

| Individuals living in household | 5 ± 2 (3–10) | 5 ± 1 (3–6) | ||||

| (Mean ± SD (Min–Max)) | ||||||

| Household member literacy | 92% | 45 | 49 | 93% | 14 | 15 |

| Child caregiver literacy | 94% | 46 | 49 | 93% | 14 | 15 |

| Unimproved latrine | 37% | 18 | 49 | 20% | 3 | 15 |

| Household refrigerator ownership | 65% | 32 | 49 | 60% | 9 | 15 |

| Electricity | 100% | 49 | 49 | 100% | 15 | 15 |

| Presence of Soap in: | ||||||

| Kitchen area | 8% | 4 | 49 | 13% | 2 | 15 |

| Toilet area | 8% | 4 | 49 | 27% | 4 | 15 |

| No household income source | 2% | 1 | 49 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| Water source type: | ||||||

| Ground water | 94% | 46 | 49 | 93% | 14 | 15 |

| Pond | 0% | 0 | 49 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| Dug well | 4% | 2 | 49 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| Piped water supply | 2% | 1 | 49 | 7% | 1 | 15 |

| Collected rainwater | 0% | 0 | 49 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| River | 0% | 0 | 49 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| Canal | 0% | 0 | 49 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| Household roof type: | ||||||

| Concrete | 4% | 2 | 47 | 7% | 1 | 15 |

| Tin | 96% | 45 | 47 | 93% | 14 | 15 |

| Hay | 0% | 0 | 47 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| Leaves | 0% | 0 | 47 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| Others | 0% | 0 | 47 | 0% | 0 | 15 |

| Sleeping rooms in household: | ||||||

| 1 sleeping room | 20% | 10 | 49 | 27% | 4 | 15 |

| 2 sleeping room | 41% | 20 | 49 | 40% | 6 | 15 |

| 3 sleeping room | 24% | 12 | 49 | 20% | 3 | 15 |

| 4 sleeping room | 14% | 7 | 49 | 13% | 2 | 15 |

| Numbers of sleeping rooms | 2.44 ± 0.99 (1–4) | 2.19 ± 0.98 (1–4) | ||||

| (Mean ± SD (Min–Max)) | ||||||

| Implementation Outcome | Implementer Perceptions | Recipient Perceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | Implementers reported that recipients generally accepted CHoBI7 delivery and viewed it as important to reduce the spread of diarrheal diseases. Development of three separate handwashing station models based on participant feedback increased acceptability of the intervention. The use of health promoters residing in the community was also viewed as an important aspect of intervention acceptability. | Most recipients appreciated CHoBI7 delivery at healthcare facilities to help prevent diarrhea in their households. Most recipients reported liking the handwashing stations they constructed as part of the intervention. Some reported that their tubewells were arsenic- and iron-free, and therefore, drinking water did not need to be treated with chlorine tablets. Most recipients liked the voice calls sent to their mobile phone from the mobile health program. Cue cards were considered valuable to promote WASH behaviors. |

| Adoption | Implementers stated that many households reported preparing their own handwashing stations during direct calls. High iron levels in water decreased chlorine effectiveness, and using homemade iron filters after chlorination reduced free chlorine concentration in stored drinking water. | Reported adoption of handwashing with soap and water treatment behaviors was high during the 7-day high-risk period and sustained to the 3-month follow-up (corresponding with structured observation and unannounced spot check reports). A high proportion of households reported preparing their own handwashing stations. |

| Appropriateness | Implementers viewed the adapted CHoBI7 program as relevant for the rural context. The iterative pilot study was viewed as useful to tailor intervention development to this context. Intervention delivery timing to severe diarrhea patients and their accompanying household members was viewed as appropriate. | Recipients generally felt that diarrheal diseases were a problem for their household. Handwashing with soap and water treatment were viewed as important interventions to protect the health of their families. There appeared to be more concern around iron contamination (aesthetic qualities of the water) than germs in tubewell water. |

| Cost | Implementers reported that the intervention had a low cost, with most households reporting already having intervention materials in their home. The cost of materials like buckets was a barrier to constructing the “bucket with tap” handwashing station for some recipients that did not have these items in their home. However this was overcome by recommending 3 different models of self-made handwashing stations, two of which did not require a bucket. | Overall cost was not considered a major barrier to constructing a handwashing station. The cost of buckets to construct the “bucket with tap” handwashing stations was a concern for some recipients who did not have one already in their home. However, most recipients constructed stations at no additional cost using materials from their homes. |

| Fidelity | Implementers faced challenges delivering CHoBI7 in healthcare facilities due to frequent interruptions from healthcare facility staff and visiting family members. Implementers also faced challenges with sending voice and SMS messages due to network problems. Most households achieved high stored-water chlorine levels. However, elevated iron concentrations in drinking water and using self-made iron filters initially presented a major challenge for intervention fidelity for water treatment. | Recipients present in the healthcare facility during intervention delivery reported receiving healthcare facility delivery of the CHoBI7 WASH module (flipbook) by a health promoter. Most recipients reported receiving voice calls; however, some recipients reported not receiving text messages. |

| Feasibility | Implementers reported that both healthcare facility visits and sending voice and SMS messages for intervention delivery was feasible. However, during the peak diarrhea season it became very challenging to deliver the intervention in the healthcare facilities due to many patients being admitted to the on the same day. | Healthcare facility delivery of CHoBI7 in a rural setting was shown to be feasible. Recipients constructing their own handwashing stations was found to be a feasible approach as well as delivery of CHoBI7 voice and SMS messages in a rural setting. |

| Penetration | Implementers reported that reaching all household members for intervention delivery in the healthcare facility was a challenge. Direct phone calls were valuable for reaching household members of diarrhea patients who were not present in the healthcare facility. | Some household members were not present in the healthcare facility when the intervention was delivered, and some were unavailable when calls came to their mobile phone. Some household members were not able to share mobile messages with their household because they were busy outside of the home. The content of the WASH module (flipbook) was not always shared with those not present in the healthcare facility when the intervention was delivered. |

| Sustainability | Implementers mentioned chlorine tablets were not locally available. | Recipient handwashing with soap and water treatment practices were sustained to the 3-month follow-up from both participant reports and from unannounced spot checks and structured observations. |

| Scalability | Implementers emphasized the need for multiple options for handwashing station models for households. For chlorination, implementers reported that iron levels in household water need to be carefully considered when making recommendations on chlorine dosing, and chlorine tablets need to be available in the local market for scaling. It was recommended that there be further engagement of healthcare facility staff in CHoBI7 program delivery. | This was not explored at the recipient level. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zohura, F.; Parvin, T.; Endres, K.; Thomas, E.D.; Hossain, Z.; Hossain, K.; Masud, J.; Minhaj, I.; Sarwar, S.; Perin, J.; et al. Formative Research for Adapting the Cholera-Hospital-Based-Intervention-for-7-Days (CHoBI7) Water Treatment and Hygiene Mobile Health Program for Scalable Delivery in Rural Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020170

Zohura F, Parvin T, Endres K, Thomas ED, Hossain Z, Hossain K, Masud J, Minhaj I, Sarwar S, Perin J, et al. Formative Research for Adapting the Cholera-Hospital-Based-Intervention-for-7-Days (CHoBI7) Water Treatment and Hygiene Mobile Health Program for Scalable Delivery in Rural Bangladesh. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020170

Chicago/Turabian StyleZohura, Fatema, Tahmina Parvin, Kelly Endres, Elizabeth D. Thomas, Zakir Hossain, Kabir Hossain, Jahed Masud, Ismat Minhaj, Sawkat Sarwar, Jamie Perin, and et al. 2025. "Formative Research for Adapting the Cholera-Hospital-Based-Intervention-for-7-Days (CHoBI7) Water Treatment and Hygiene Mobile Health Program for Scalable Delivery in Rural Bangladesh" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020170

APA StyleZohura, F., Parvin, T., Endres, K., Thomas, E. D., Hossain, Z., Hossain, K., Masud, J., Minhaj, I., Sarwar, S., Perin, J., Bahauddin, M., Islam, M. N., Adnan, S. D., Al-Kabir, A., Faruque, A. S. G., & George, C. M. (2025). Formative Research for Adapting the Cholera-Hospital-Based-Intervention-for-7-Days (CHoBI7) Water Treatment and Hygiene Mobile Health Program for Scalable Delivery in Rural Bangladesh. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020170