Use of a Critical Constructivist, Community-Engaged Approach to Understand Commercial Determinants of Breast Cancer: The Situational Scoping Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pilot Study Background

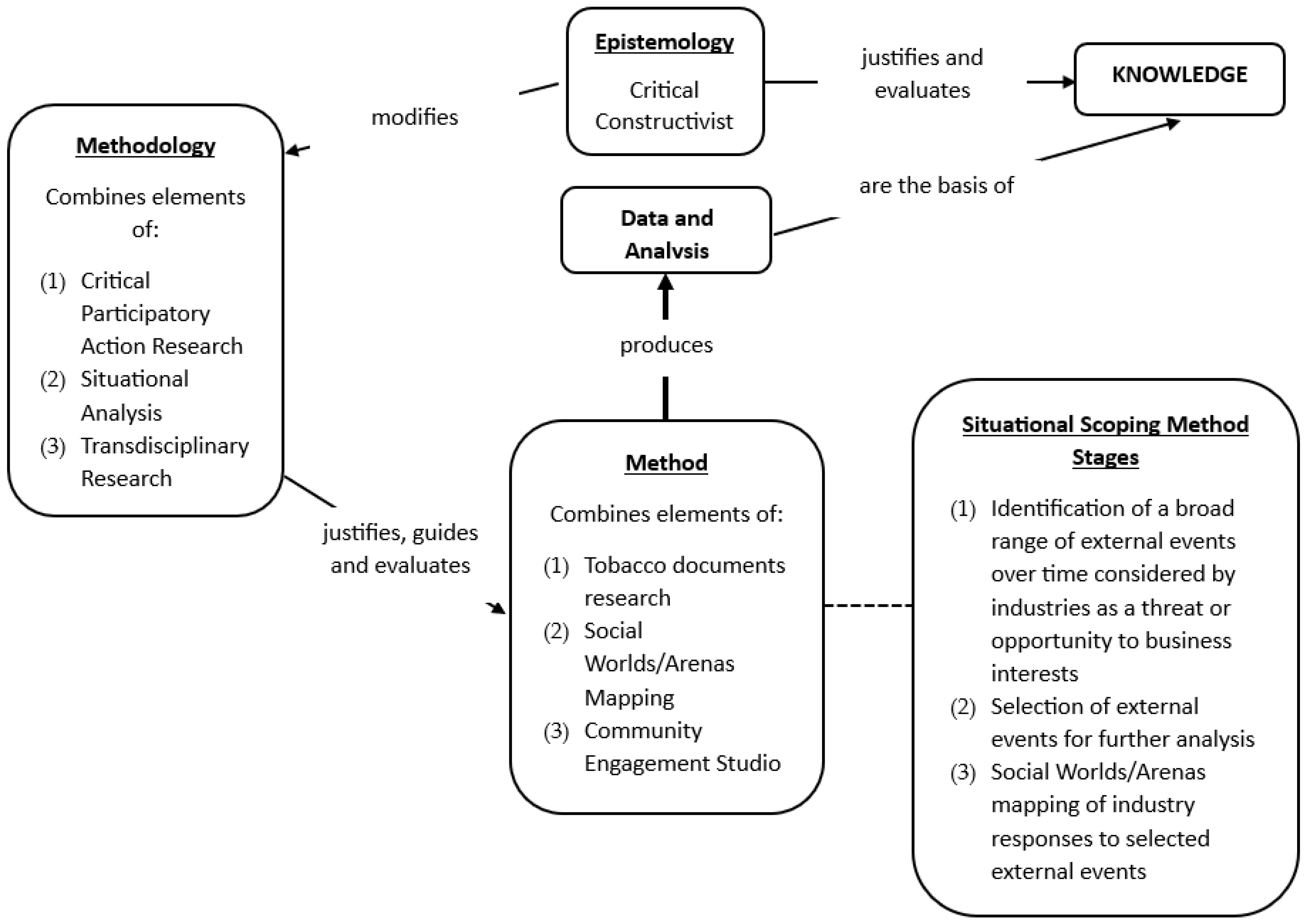

3. The Situational Scoping Method

- Identification of a broad range of external events over time perceived by industries as a threat or opportunity to business interests.

- Selection of a sample of external events for further analysis.

- Social worlds/arenas mapping of industry responses to selected external events.

3.1. Epistemological Influences

Critical Constructivism

3.2. Methodologies Employed

3.2.1. Critical Participatory Action Research

3.2.2. Situational Analysis

3.2.3. Transdisciplinary Orientation

3.3. Methods Selected

3.3.1. Tobacco Documents Research

3.3.2. Social Worlds/Arenas Mapping

3.3.3. Community Engagement Studio

4. Situational Scoping Method Procedures in the Pilot Study

5. Summary of Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Potential Advantages of the Situational Scoping Method

6.2. Challenges in Using the Situational Scoping Method

6.3. Added Value of the Situational Scoping Method

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDOH | Commercial Determinants of Health |

| CBCRP | California Breast Cancer Research Program |

| IDL | Industry Documents Library |

| RFP | Request for Proposals |

| BCAction | Breast Cancer Action |

| CPAR | Critical Participatory Action Research |

| CE Studio | Community Engagement Studio |

References

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tasker, K.; Taketa, R.; Macquarie, C.; Deardorff, A. Digital Archives and Data Science: Building Programs and Partnerships for Health Sciences Research. In Advances in Library and Information Science; Mani, N.S., Cawley, M.A., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCSF Library. Industry Documents Library/Bibliography—Publications Based on Industry Documents. In Industry Documents Library; UCSF Library: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/biblio/#q=*%3A*&cache=true&count=1173 (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Bero, L. Implications of the Tobacco Industry Documents for Public Health and Policy. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2003, 24, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschhorn, N. The Tobacco Industry Documents: What They Are, What They Tell Us, And How to Search Them; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mamudu, H.M.; Gonzalez, M.; Glantz, S. The Nature, Scope, and Development of the Global Tobacco Control Epistemic Community. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 2044–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- UCSF Library. Industry Documents Library/About IDL/Overview. In Industry Documents Library; UCSF Library: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/about/overview/ (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Anderson, S.J.; McCandless, P.M.; Klausner, K.; Taketa, R.; Yerger, V.B. Tobacco documents research methodology. Tob. Control 2011, 20, ii8–ii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, S.M.; Little, M. Justifying Knowledge, Justifying Method, Taking Action: Epistemologies, Methodologies, and Methods in Qualitative Research. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balbach, E.D. Tobacco industry documents: Comparing the Minnesota Depository and internet access. Tob. Control 2002, 11, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balbach, E.D. Beyond quagmires: The evolving quality of documents research. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, R.E.; Balbach, E.D. Tobacco industry documents: Treasure trove or quagmire? Tob. Control 2000, 9, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, S.M. Tobacco document research reporting. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, J. Tobacco control, global health policy and development: Towards policy coherence in global governance. Tob. Control 2012, 21, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- California Breast Cancer Research Program. Request for Proposal: Investigating Industry Influence Over Scientific Information on Breast Cancer and the Environment, Exploring the UCSF Industry Documents Library. 2021. Available online: https://cbcrp.org/files/pbc-funding/investigating-industry-influence-rfp.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Breast Cancer Action. Homepage. 2024. Available online: https://www.bcaction.org/ (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- Clarke, A.E.; Friese, C.; Washburn, R.S. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Interpretive Turn; SAGE Publ. Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/situational-analysis/book238990 (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Han, E.; Crosbie, E.; Ling, P.; Perez, S.; Khan, H.; Hiatt, R.; Kearns, C. Tobacco industry influence on breast cancer research, policy and public opinion: Scoping the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents. Tob. Control 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincheloe, J.L. Critical Constructivism Primer; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kincheloe, J.L. From Constructivism to Critical Constructivism. In Critical Constructivism Primer; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 1–40. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eue&AN=35947097&site=ehost-live (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Fine, M.; Torre, M.E. Essentials of Critical Participatory Action Research; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Essentials-Critical-Participatory-Research-Qualitative/dp/1433834618 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Clarke, A.E. Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Garrety, K. Dietary Policy, Controversy, and Proof: Doing Something versus Waiting for the Definitive Evidence. In Silent Victories, 1st ed.; Ward, J.W., Warren, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadorn, G.H.; Hoffmann-Riem, H.; Biber-Klemm, S.; Grossenbacher-Mansuy, W.; Joye, D.; Pohl, C.; Wiesmann, U.; Zemp, E. Handbook of Transdisciplinary Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.E.; Friese, C.; Washburn, R.S. Doing Social Worlds/Arenas Maps. In Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Interpretive Turn; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, Y.A.; Israel, T.L.; Williams, N.A.; Boone, L.R.; Schlundt, D.G.; Mouton, C.P.; Dittus, R.S.; Bernard, G.R.; Wilkins, C.H. Community Engagement Studios: A Structured Approach to Obtaining Meaningful Input from Stakeholders to Inform Research. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 1646–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meharry-Vanderbilt Community Engaged Research Core. Community Engagement Studio Toolkit 2.0. Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research. 2009. Available online: https://victr.vumc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/CESToolkit-2.0.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Fisher, C.D. Padlet: An Online Tool for Learner Engagement and Collaboration, Available at https://Padlet.com. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.E.; Friese, C.; Washburn, R.S. Doing Positional Maps. In Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Interpretive Turn; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Whiteboard Tools Reference & Glossary-Jamboard Help. 2024. Available online: https://support.google.com/jamboard/answer/7383648?hl=en (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Maani, N.; Petticrew, M.; Galea, S. (Eds.) The Commercial Determinants of Health; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pink, S.; Horst, H.; Lewis, T.; Hjorth, L.; Postill, J. Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, A.N. Ethnography in the Digital Internet Era: From Fields to Flows. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 650–668. [Google Scholar]

| Project Team Procedures | Description | Research Team Procedures | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team Formation | The project was led by a principal investigator (CK) in collaboration with Breast Cancer Action (BCAction). Initial contact was established after both parties attended a CBCRP informational session in February 2021. Two exploratory meetings were held to discuss a potential collaboration. BCAction brought experience working with a UCSF research team and was familiar with industry tactics, manipulation of science, and environmental contributors to breast cancer, though with limited prior experience using the IDL. The organization agreed to partner on the CBCRP grant application in March 2021. The project was also supported by two UCSF IDL archivists and a facilitator with expertise in participatory action research. | Team Formation | A transdisciplinary research team was assembled, comprising 11 investigators with expertise in industry documents research, tobacco, food, and chemical industry studies, public health, communications, medical anthropology, sociology, political science, environmental health, and breast cancer epidemiology. The team included participants at all career stages, from master’s students to senior faculty. Supplemental funding was provided by the UCSF Center for Tobacco Control and Education and the UCSF Environmental Research and Translation for Health Center to support two postdoctoral scholars. Additional support for two master’s students came from the University of Nevada, Reno. |

| Grant Submission | The PI, BCAction, and the facilitator collaborated through email and Zoom meetings to co-develop grant deliverables, including the lay abstract, BCAction’s letter of commitment, advocacy involvement plan, program responsiveness narrative, specific aims, milestones, and the research plan. The proposal was funded in June 2021, with a start date of 1 August 2021, and a 12-month project period. | ||

| Stage 1: Identification of a broad range of external events perceived by IDL industries as a threat or opportunity to business interests | |||

| (1) UCSF IDL Documents Training | Training needs for this project included educating project team members unfamiliar with the IDL on the public health impact of industry documents work and instruction on how to search the digital collections. IDL archivists conducted an initial IDL training session for BCAction and research team members who would be searching the documents in August. Training content included: overview of the IDL (how documents are obtained and ingested, how to search one industry vs. one collection at a time, understanding duplicate documents, searching metadata, and features of an individual IDL account); IDL search features and tools (browse, date ranges, facets, document types including restricted, formerly confidential, court case, area/box/folder, mentioned); and search demonstrations. A follow-up training was held in December on advanced search strategies including the snowball method, building, and revising search queries, advanced search tips—wildcard/fuzzy search, proximity search. | (2) Assigning the IDL Collections | After the preliminary search of the entire IDL for the search term “breast cancer” returned 55 K documents, the research team met to decide how to assign analysis of the documents to individual members. Four researchers were assigned to the tobacco industry collections. One researcher was assigned to the food industry collections, and one researcher was assigned to the chemical, drug, and fossil fuel industry collections (combined). |

| (4) Community Engagement Studio #1 | The first CE Studio meeting was held in late August. The PI, BCAction and facilitator met prior by Zoom and communicated subsequently by email to plan the first project meeting and co-create the agenda. Project team members received an agenda ahead of time to prepare them to give input. At the CE Studio, an overview of the grant and key deliverables were reviewed. The facilitator led a roles and partnership discussion. Team members were asked to share thoughts on what they uniquely brought to the collaboration and what they were hoping to learn. Successes and challenges of partnerships were discussed, including learnings from past experiences. Partnership principles were developed. The research team shared preliminary findings on collection and document characteristics and received feedback from the larger project team on the relevance of initial themes, organizations, and actors to the research questions. Additional relevant search terms were suggested. | (3) IDL Collection Characteristics | During August, research team members collected data on the number of collections containing documents returned with the search term “breast cancer.” collection characteristics (type, provenance) frequency and distribution of documents (e.g., by decade, by product type, document type). For example, the largest number of tobacco and food industry documents returned were produced between the 1970s and 1990s, most drug industry documents were produced in the 1990s and 2000s, most chemical industry documents were produced in the 2000s, and most fossil fuel industry documents were produced in the 1990s. Initial impressions on general themes of document content were recorded, including important time periods, tobacco brands, foods, chemicals and organizations of interest. Four ten-minute presentations were created in preparation to share this information at the first CE Studio. |

| (5) Identifying External Events of Interest | Researchers sorted documents returned with the search term “breast cancer” by decade and were instructed to identify “high value” IDL documents, such as internal memos and reports, formerly confidential and privileged documents. Document abstracts were screened for relevance to the project’s research questions before reading a document in-depth. Close attention was paid to industry surveillance of the policymaking environment, the news media and the scientific media for external events related to breast cancer perceived by the industries as threatening, as well as the research, public relations, marketing, and advertising activities planned in response. Situations of interest were tobacco, food, drug, chemical, and fossil fuel industry responses to external events over time related to breast cancer perceived by these industries as threats or opportunities to demand for their products. Using Padlet, a cloud-based real-time collaborative web platform in which users can upload, organize, and share content to virtual bulletin boards [29], researchers recorded potential situations of interests, including various elements and actors, together with links to high-value documents. Researchers had flexibility with how Padlet boards were constructed, which was influenced by archive size and number of collections with relevant documents. Investigators incorporated research memos into the mapping process by moving between document searches, creating, and editing situational maps, and writing research memos to aid in making conceptual and relational connections. Memos captured document keyword search strategies and documents retrieved and reviewed. The research team met weekly to review progress and received input from other research team members on searches, findings, contextualization, and advice to avoid “analysis paralysis.” At the end of the scoping and initial assessment phase, researchers were asked to construct one Padlet Board documenting the identified situations of interest, key actors, and industry discourses. Fifty-three breast cancer-related external events were identified across the 5 IDL collections ranging from the 1969 U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare Commission on Pesticides and their Relationship to Environmental Health to the 2017 Environmental Protection Agency Cancer Assessment Review Committee’s review of glyphosate toxicity (Table 2). Events were grouped by industry into topics: tobacco industry archives—genetic causation, smoking, environmental tobacco smoke, smoking and reproductive health, breast cancer prevalence, aspirin use, and dietary explanations for breast cancer; chemical and fossil fuel industry archives—glyphosate, benzene; drug industry archives-Premarin; food industry archives—chemicals/pesticides in foods, dietary fat, alcohol, synthetic estrogen, growth hormones, obesity and physical activity. | ||

| Stage 2: Selection of external events for further analysis | |||

| (6) Community Engagement Studio #2 | The second quarterly CE Studio was held in November. After a brief overview of the 2nd phase of the project, research team members presented the results of their initial scoping and assessment work, including the Padlet Boards documenting potential situations of interest. A facilitated discussion was conducted to elicit feedback on events/situations most likely to reveal data related to our research questions was elicited from the project team. Ten topic areas were selected for further analysis: (1) Tobacco industry-funded research about breast cancer (1970s–1980s); (2) Tobacco industry-funded research about breast cancer (1990s); (3) 1997 California Environmental Protection Agency Report: Health Effects of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke; (4) 2005 California Environmental Protection Agency Report: Health Effects of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke: (5) Association of Hormonal Replacement Therapy with Breast Cancer; (6) Glyphosate and Breast Cancer; (7) Benzene and Breast Cancer; (8) Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and Breast Cancer; (9) Recombinant Bovine Somatotropin and Breast Cancer; (10) Dietary Fat and Breast Cancer. | (7) Additional Document Searches | The research team conducted additional document searches to support an in-depth review of each topic (Table 3). We found that the IDL contains at least 13,186 documents indicating that the tobacco industry’s Council for Tobacco Research (CTR) sponsored research projects related to breast cancer between the 1970s–1990s; 1067 documents related to Philip Morris’ and RJ Reynolds’ responses to events leading up to the 1997 and 2005 California Environmental Protection Agency Report on environmental tobacco smoke (ETS); at least 175 documents related to Wyeth-Ayerst’s communication campaign developed in response to emerging of evidence in 2002 that their hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) drug Premarin increased breast cancer risk, and that HRT was not beneficial to women with or at increased risk for coronary heart disease; at least 80 documents related to Monsanto’s response to the 2015 International Agency for Research on Cancer’s systematic review of the carcinogenic potential of glyphosate which concluded it is a probable carcinogen; at least 212 documents related to Shell Oil and other oil industry actors’ (e.g., American Petroleum Institute) hiring of the consultant group Environ Corporation to re-analyze data reviewed in 1984 by the California Department of Health Services to cast doubt on the value of animal models to understanding benzene exposure risk in humans-including mouse models which demonstrated ovarian and mammary gland tumors; 102 documents related to DDT and breast cancer; 143 documents related to recombinant bovine somatotropin, breast cancer, and Monsanto’s relationship with the Harvard University Department of Nutrition in 1980s/90s; and over 10,000 documents related to dietary fat and breast cancer. |

| Stage 3: Social worlds/arenas mapping of industry responses to selected external events | |||

| (8) Social worlds/arenas mapping and memoing training | CK provided training to the research team on identifying situations of interest; creating social worlds/arenas maps; and on memoing. SA readings were provided on social words/arenas including exemplar projects [18,26,30]. The research team received guidance on drafting a final project memo, including a memo template. Memos included documentation of search strategy, summaries of collection and document characteristics, scoping and initial assessment processes, in-depth review processes, and a summary of key findings, contributions of the research to the specific aims, and implications of the findings to breast cancer prevention, treatment, and policy. | ||

| (9) Preliminary social worlds/arenas mapping | The research team began constructing social worlds/arenas maps using Google Jamboard [31] for each of the ten topics selected for further analysis. Analytic “close-ups” were created for each on social worlds/arena maps with an intense focus on identifying research related to links between environmental exposures and breast cancer and public relations activities designed to influence public opinion related to environmental exposures and breast cancer [18]. The research team met weekly to review progress and received input from other research team members. At the end of the in-depth review phase, researchers were asked to prepare brief presentations on their social worlds arenas maps. | ||

| (10) Community Engagement Studio #3 | The third quarterly CE Studio was held in February. After an overview of the 3rd phase of the project, research team members presented the results of their in-depth review of documents, including preliminary social worlds/arenas maps. A facilitated discussion was conducted to elicit feedback on content and suggested revisions of the social worlds/arenas maps, as well as key material to include in the final project memos. | ||

| (11) Iterative social worlds/arenas mapping | Social worlds/arenas maps were finalized and compiled with the final project memos by the research team into one pdf and made available to the entire project team. The research team created final presentations of results. | ||

| (12) Advocacy Focus Groups | To inform efforts to disseminate project findings, BCAction conducted 3 focus groups with partners and key stakeholders in June 2022. Focus groups were organized by topic: (1) tobacco industry findings (2) food industry findings, and (2) drug and chemical industry findings and lasted one hour. After introductions, participants were shown a 10 min pre-recorded presentation delivered by members of the research team. BCAction then asked participants 11 questions to elicit feedback on participants prior knowledge of the subject matter, relevance of the findings to participants, ideas for dissemination, and use potential of the IDL for future advocacy work. | ||

| (13) Community Engagement Studio #4 | The final CE Studio was held in May. After a brief overview of the final phase of the project, BCAction presented focus group results and research team members presented a high-level summary of their final social worlds/arenas maps and memos. A facilitated discussion was conducted to elicit feedback related to dissemination planning and manuscript preparation. Findings were used to apply for a CBCRP dissemination supplement, which we received to support two symposiums held in 2023. | ||

| Year | External Events |

|---|---|

| Archive: Tobacco Industry Documents | |

| Topic: Genetic Explanations for Breast Cancer | |

| 1970s | Hereditary cancer research |

| Topic: Smoking and Breast Cancer (Positive and Negative Associations) | |

| 1977 | Potential Association Between Smoking and Breast Cancer: Effects of X-Rays |

| 1979–1983 | Negative Association Between Smoking and Breast Cancer (Opportunity for Industry) |

| 1980s–1990s | Studies Linking smoking and breast cancer |

| 1986 | Surgeon General Reports |

| 1988 | California Proposition 99 |

| 1995 | Evidence of Increased Risk for Breast Cancer for Long-Time Smokers |

| 1996 | Evidence of Weak Association Between Active and Passive Smoking and Breast Cancer |

| 1999 | Evidence of Modest Inverse Relationship with Current Smokers and Breast Cancer (Not Past Smokers) |

| 1999 | Evidence of Real Association for Passive and Active Smokers and Breast Cancer |

| Topic: Secondhand/Environment Tobacco Smoke and Breast Cancer | |

| 1980s | Studies about secondhand smoking and cancer |

| 1990, 1993 | California EPA’s guidelines on indoor smoking policy and designation of secondhand smoking as carcinogen |

| 1997 | California Environmental Protection Agency Report: Health Effects of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke |

| 2005 | California Environmental Protection Agency Report: Health Effects of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke |

| Topic: Smoking, Reproductive Health and Breast Cancer | |

| 1983 | Evidence that Heavy Smoking May Lower Age of Menopause |

| 1994 | Evidence that Women who Had Abortions Have Higher Risk of Breast Cancer |

| Topic: Prevalence of Breast Cancer | |

| 1986 | Lung cancer has surpassed breast cancer death in females |

| Topic: Aspirin Use and Breast Cancer | |

| 1994 | Significant Negative Relationship Between Aspirin Use and Breast Cancer |

| Topic: Dietary Explanations for Breast Cancer | |

| 1997–1998 | Carcinogens in Foods |

| Archive: Chemical Industry Documents and Fossil Fuel Industry Documents | |

| Topic: Glyphosate and Breast Cancer | |

| 2013 | Thongprakaisang et al. 2013 Study (Food and Chemical Toxicology): Animal study evidencing possible estrogen effects of glyphosate exposure. |

| 2014 | Séralini 2014 Mouse Study (Food and Chemical Toxicology): Long-term (2 year) exposure of rodents to Roundup (a glyphosate-inclusive compound) is found to be significantly related to the development of mammary tumors. |

| 2015 | International Agency for Research on Cancer 2015 statement on glyphosate carcinogenicity. |

| 2015, 2017 | Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Cancer Assessment Review Committee 2015, 2017 review of glyphosate toxicity. |

| Topic: Benzene and Breast Cancer | |

| 1970s | Occupational Safety and Health Administration 1970s review and designation of benzene as carcinogenic. |

| 1980s | 1980s Occupational Health Movement with antecedents in the 1930s–1950s. |

| 1984 | California Department of Health Services 1984 election of benzene “as a candidate substance for listing as a toxic air contaminant.” |

| Archive: Drug Industry Documents | |

| Topic: Premarin and Breast Cancer | |

| 2002 | The controversial 2002 findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study Follow-Up (HERS II) cohort studies indicating the potential link between hormone replacement therapy and the development of breast cancer and heart disease. |

| Archive: Food Industry Documents | |

| Topic: Chemicals/Pesticides in Foods and Breast Cancer | |

| 1969 | Pesticides and Breast Cancer: Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare Commission on Pesticides and their Relationship to Environmental Health |

| 1969 | DDT and Breast Cancer: Cyclamate Ban under Delaney Clause could justify DDT ban |

| 1971 | Launch of War on Cancer—attention to environmental contaminants—National Cancer Act |

| 1974 | National Cancer Act (Amendment) |

| 1978 | Chemical and Physical Agents in the Environment Cause Cancer: Publication of The Politics of Cancer, Samuel Epstein, MD—vast media coverage and attention in Washington DC |

| 1978 | Publication of ‘Origins of Human Cancer’ |

| 1980s–2000s | Media attention to environmental/chemical causes of cancer (e.g., Love Canal, Alar Scare) |

| 1993/5 | National Academy of Sciences Report Pesticides in the Diet of Infants and Children (Philip Landrigan, Chair) |

| 1996 | Book—Our Stolen Future links DDT/DDE to breast cancer |

| 1990s | Emerging Evidence on Endocrine Disruptors and breast cancer |

| Topic: Dietary Fat and Breast Cancer | |

| 1975 | Dietary Fat and Breast Cancer: Conference on Nutrition in the Causation of Cancer |

| 1975 | Dietary Fat and Breast Cancer: NCI forms Diet, Nutrition and Cancer Program Advisory Committee |

| 1976 | Burkitt’s Fiber Hypothesis of Cancer gaining popularity |

| 1977 | Dietary fat and breast cancer: US dietary goals |

| 1978 | Dietary Fat and Breast Cancer: NRC Diet, Nutrition and Cancer publishes interim guidelines |

| 1979 | National Cancer Institute Statement on Diet, Nutrition, and Cancer by Arthur Upton to Subcommittee on Nutrition, Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry |

| 1980 | NCI Statement on Diet, Nutrition, and Cancer by Arthur Upton to Subcommittee on Nutrition, Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry |

| 1982 | National Research Council panel concludes dietary fat suggestive of causal link to breast cancer |

| 1983 | NIH/NCI Prevention Subcommittee: Planning for nutrition and breast cancer studies |

| 1985 | NCI Cancer/breast cancer and nutrition studies—controversy over methodology |

| 1990s | American Cancer Society names lung cancer as #1 cancer in women |

| Topic: Alcohol and Breast Cancer | |

| 1977 | Beer-drinking and breast cancer link: emerging research |

| 1999 | evidence of association between alcohol consumption and breast cancer |

| Topic: Synthetic Estrogen and Breast Cancer | |

| 1977/78 | Diethylstilbestrol in meat/dairy linked to breast cancer: emerging research |

| 1978 | DES in meat and dairy linked to breast cancer: Nader Group demands ban on DES due to breast cancer threat |

| Topic: Growth Hormones and Breast Cancer | |

| 1995 | Massachusetts introduces bill to require bovine somatotropin (BST) labeling for milk |

| 1997 | NYC proposes to ban purchase of rBST milk by city agencies and board of education (pushed by New York Green Party) |

| Topic: Obesity, Physical Activity and Breast Cancer | |

| 2000s | Sugar/Obesity/Fiber links to cancer |

| Research Team Member | Archives/Collections Assigned | Documents Returned with Search Term “Breast Cancer” | Topics Selected by Project Team for In-Depth Review | Documents Returned with Additional/Focused Document Searches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Team Member 1 | Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Archive Tobacco Institute | 13,770 |

| “breast cancer AND grant” (CTR only) = 3231 “estrogen receptor” AND smoking = 241 “endocrine disruptor” = 20 “breast cancer advisory center” = 30 “breast cancer AND EPA” = 372 “hereditary AND breast cancer” = 1528 “breast cancer AND ETS” = 7794 |

| Center for Tobacco Research (CTR) | 7377 | |||

| Research Team Member 2 | Philip Morris | 13,317 |

| “breast cancer” AND (“environmental tobacco smoke” OR “secondhand smoke” OR CALEPA OR “surgeon general” or “premenopausal” or “postmenopausal”) = 1067 |

| RJ Reynolds | 8831 | |||

| Lorillard | 2615 | |||

| Brown and Williamson | 1365 | |||

| American Tobacco | 887 | |||

| Topical Collections | 2046 | |||

| Additional Tobacco Documents | 4075 | |||

| Research Team Member 3 | Drug Industry Documents Archive | 549 |

| “breast cancer” and Premarin = 175 “women’s health research institute” = 79 |

| Chemical Industry Documents Archive | 169 |

| “breast cancer” AND glyphosate = 80 “GMO Answers” (Entire IDL) = 191 | |

| Fossil Fuel Industry Documents Archive | 15 |

| “breast cancer” AND benzene (chemical and fossil fuel) = 64 documents “Environ Corporation AND benzene” (Entire IDL) = 212 “Exxon AND breast cancer” (Entire IDL = 938 documents | |

| Research Team Member 4 | Food Industry Documents Archive | 842 |

| “breast cancer” and (DDT OR DDE) = 102 “breast cancer” and (DDT or DDE) in entire IDL = 4119 “breast cancer” AND (“American Council on Science and Health” OR ASCH OR “international life sciences institute” OR ILSI) in entire IDL = 1781 “Harvard Human Nutrition Institute” = 221 |

| “Monsanto” (Stare collection) = 143 | |||

| “fat AND breast cancer” = 626 “dietary fat and cancer” in entire IDL = 10,010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kearns, C.E. Use of a Critical Constructivist, Community-Engaged Approach to Understand Commercial Determinants of Breast Cancer: The Situational Scoping Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121873

Kearns CE. Use of a Critical Constructivist, Community-Engaged Approach to Understand Commercial Determinants of Breast Cancer: The Situational Scoping Method. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121873

Chicago/Turabian StyleKearns, Cristin E. 2025. "Use of a Critical Constructivist, Community-Engaged Approach to Understand Commercial Determinants of Breast Cancer: The Situational Scoping Method" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121873

APA StyleKearns, C. E. (2025). Use of a Critical Constructivist, Community-Engaged Approach to Understand Commercial Determinants of Breast Cancer: The Situational Scoping Method. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121873