Climate, Health, and Urban Green Infrastructure: The Evidence Base and Implications for Urban Policy and Spatial Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What evidence exists on the health co-benefits of UGI-based adaptation?

- What are the policy implications of such evidence, especially urban policy and spatial planning?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

- UGI terms include synonyms (e.g., nature-based solutions), types (e.g., parks, green roofs), and wildcard terms (e.g., urban green*).

- Climate adaptation terms include cognate concepts (e.g., climate change, climate crisis), UGI’s main climate benefits (heat reduction, flood management, air quality), and extreme weather events (e.g., wildfires).

- Health terms include related terms (e.g., health effects, human health), physical health, mental health, well-being, and related outcomes (e.g., diseases, mortality, depression, happiness).

2.2. Literature Screening and Selection

- Published in a peer-reviewed journal.

- Contained empirical data analysis (observational, experimental, or model-based).

- Examined urban green elements as distinct or independent objects, rather than as part of a composite spatial intervention.

- Included at least one climate element as a factor of investigation.

- Reported at least one health-related outcome.

- Conducted in urban contexts.

- Assessed the health impacts of green elements and climatic factors separately, without exploring the interactions between them.

- Were review papers, conceptual papers, dissertations, conference proceedings, or non–peer-reviewed gray literature.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

- Publication year;

- Location of the study (city and country);

- Population group (e.g., children, adults, elderly, women, men);

- Type, scale, and measurements/indicators of UGI;

- Climate adaptation benefits covered;

- Physical health, mental health, and well-being benefits examined or resulting from the studied climate adaptation measures;

- Main research findings;

- Policy implications for spatial planning and built environment policy design.

2.4. Limitations

3. Results

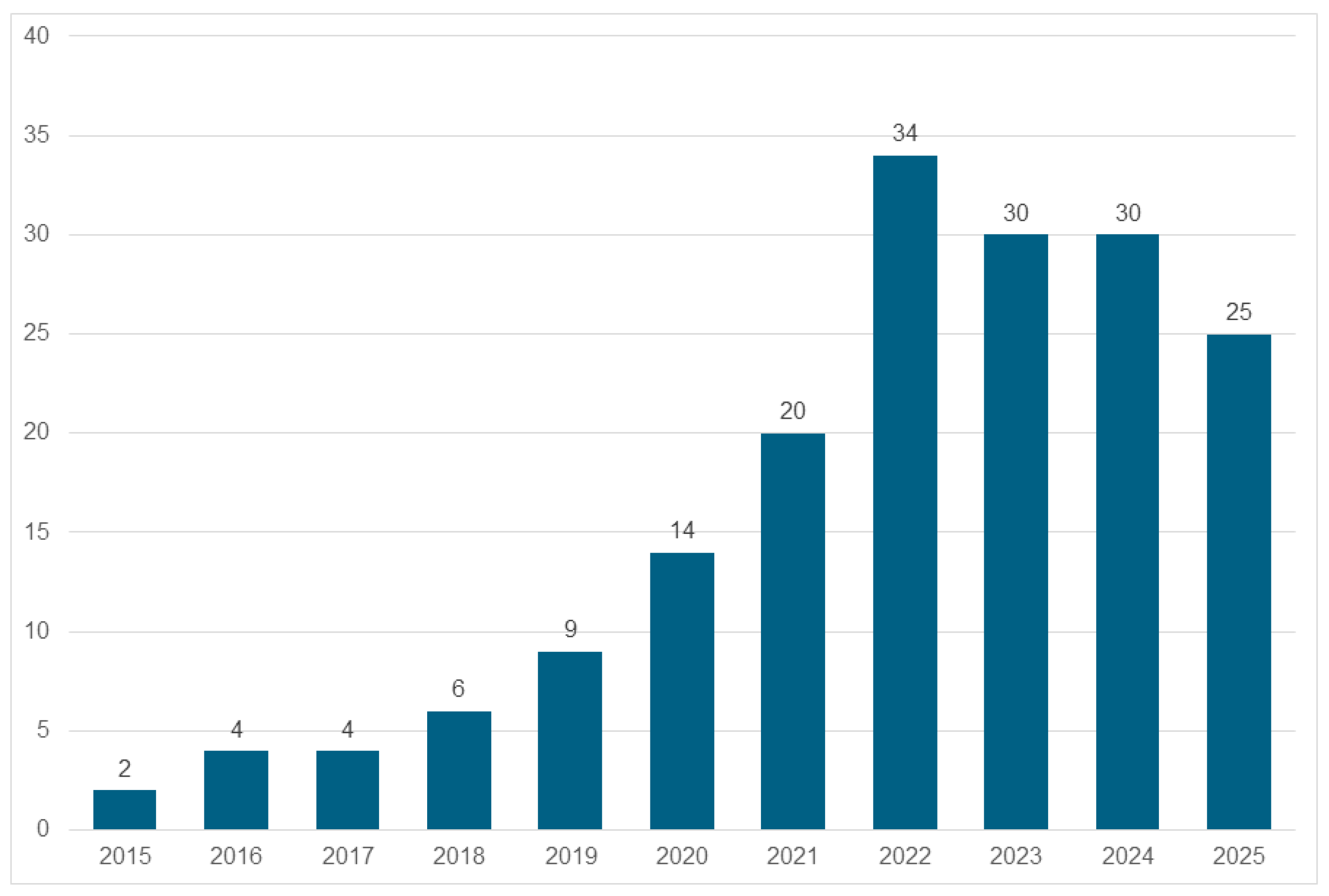

3.1. The Longitudinal and Geographical Distribution of Studies

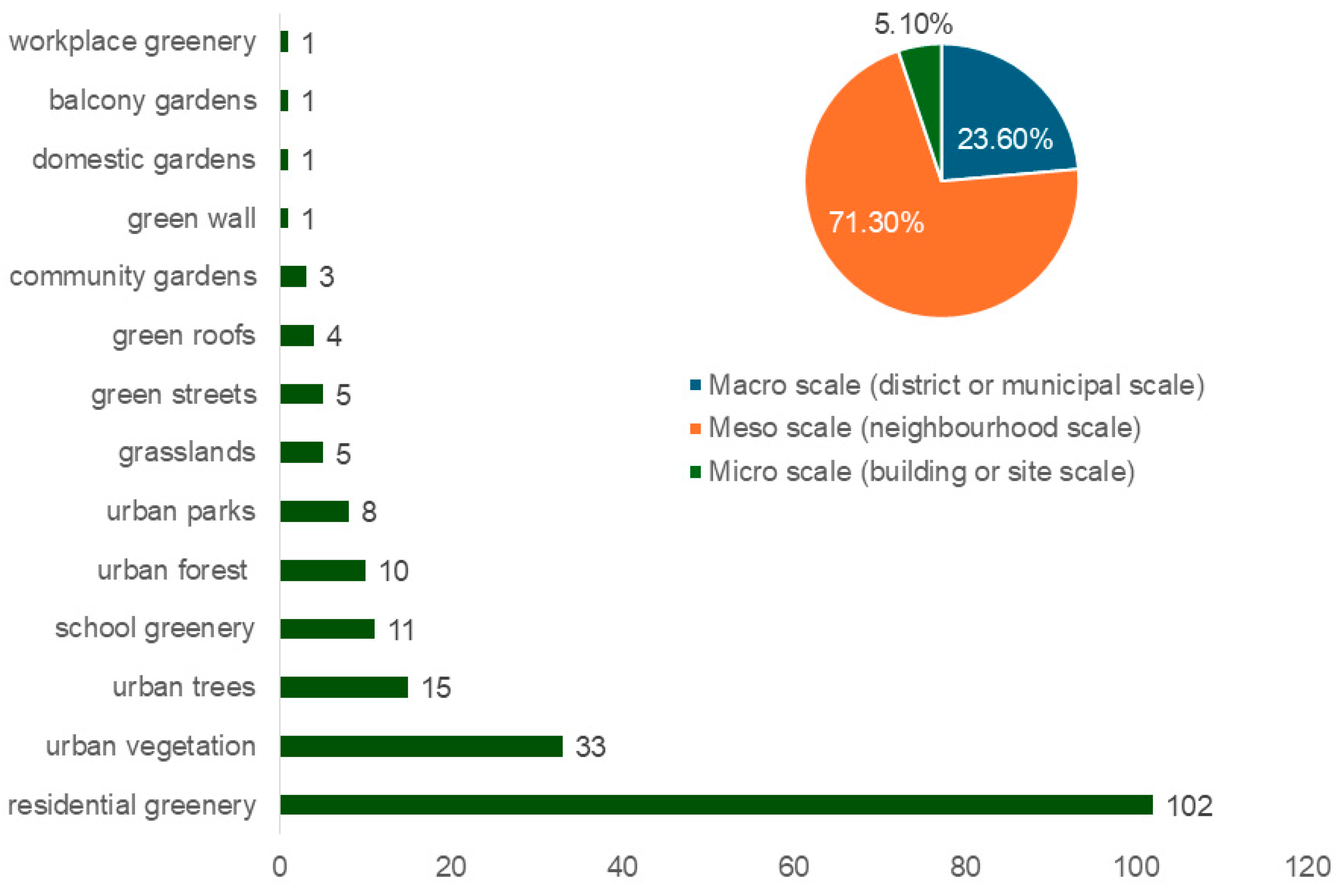

3.2. Classification of Studies by UGI Type and Scale

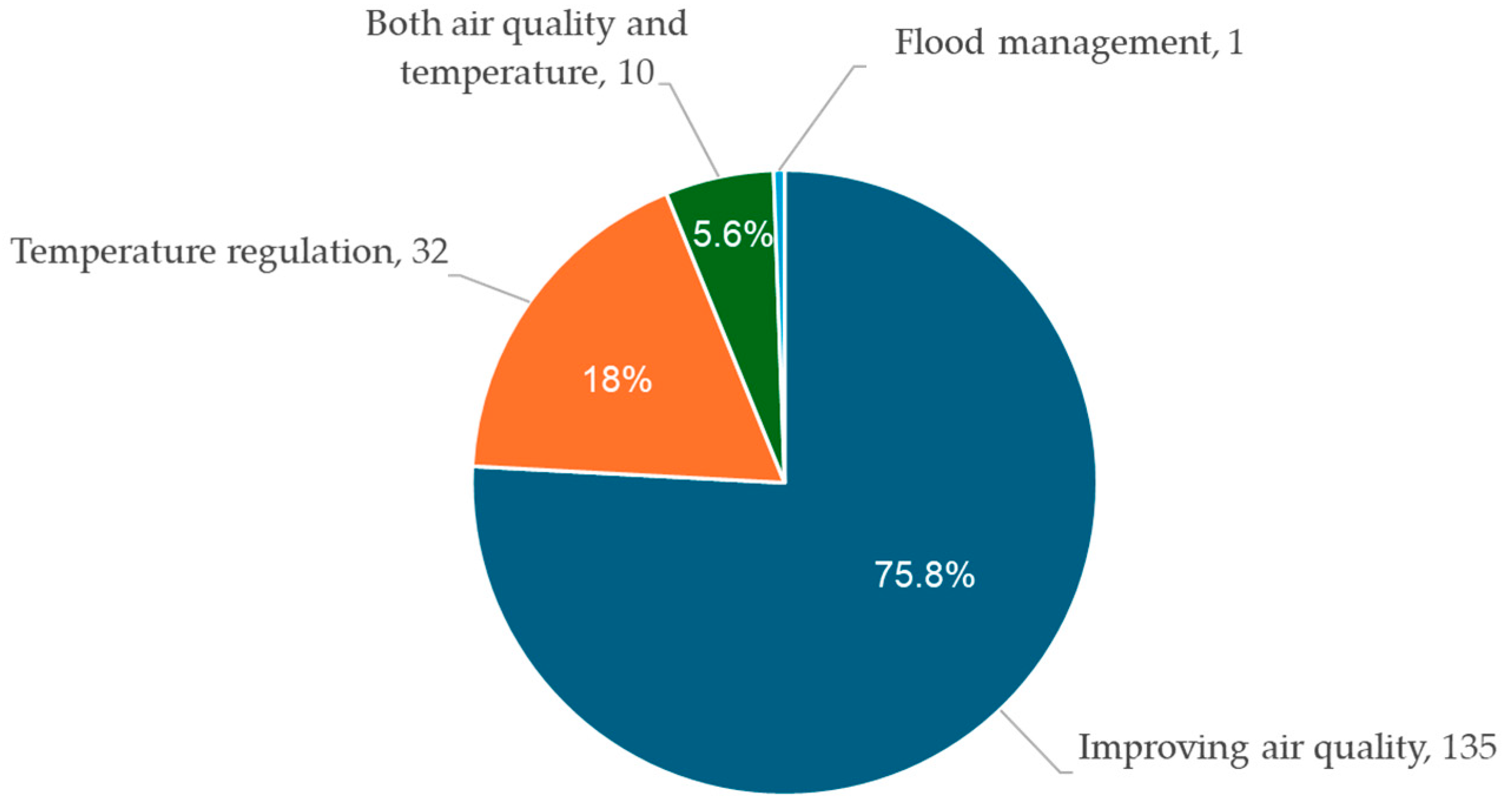

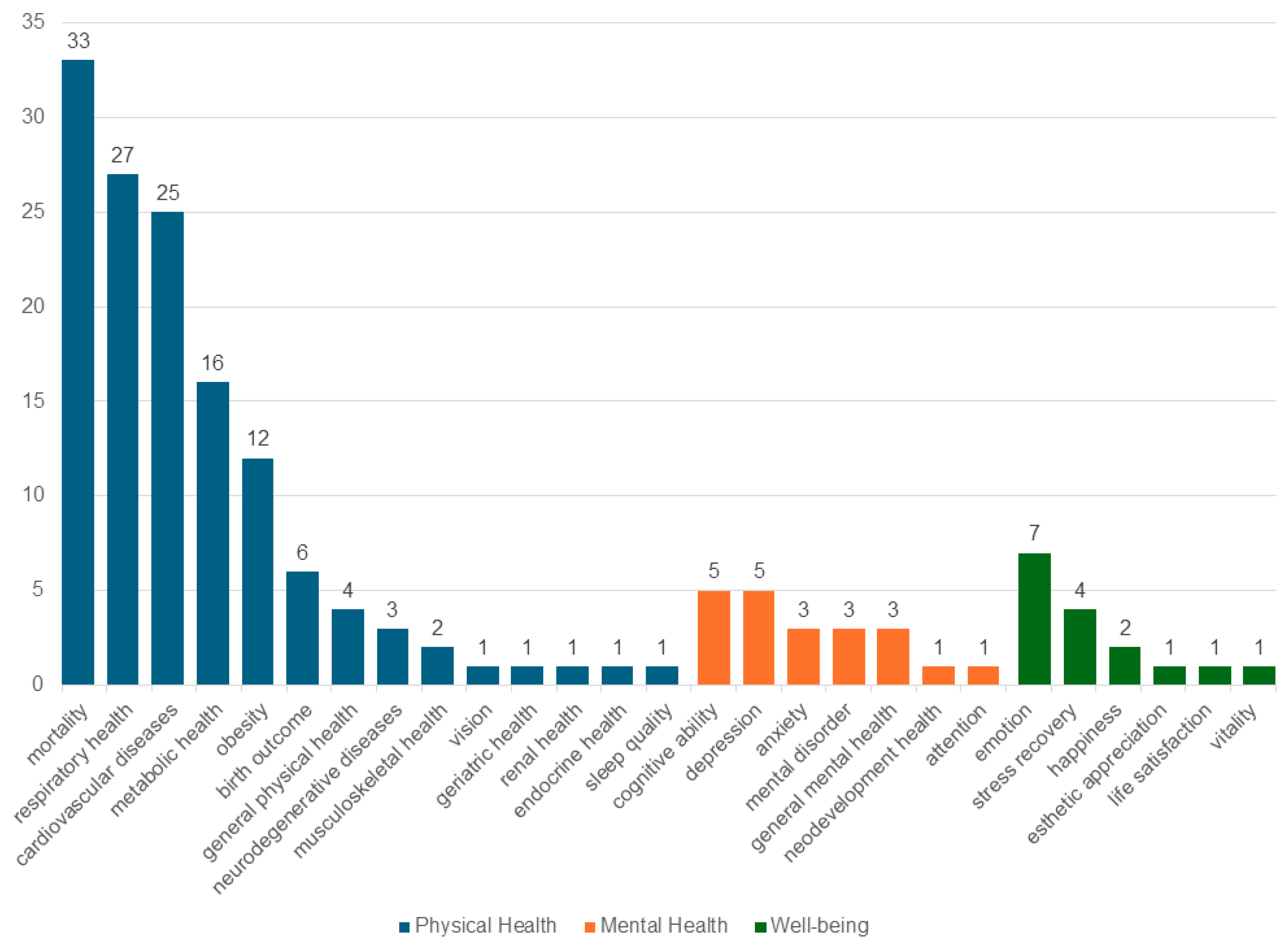

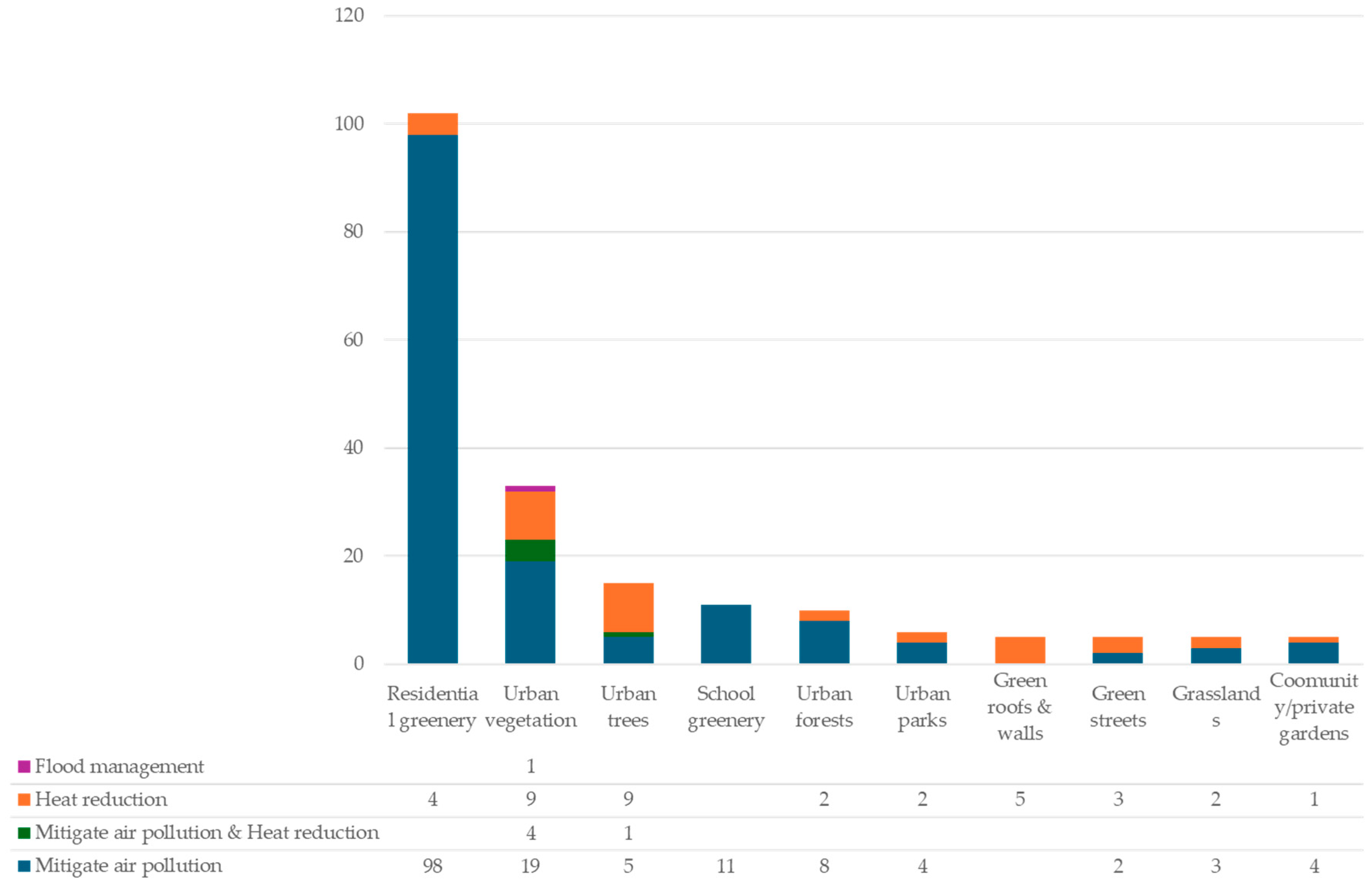

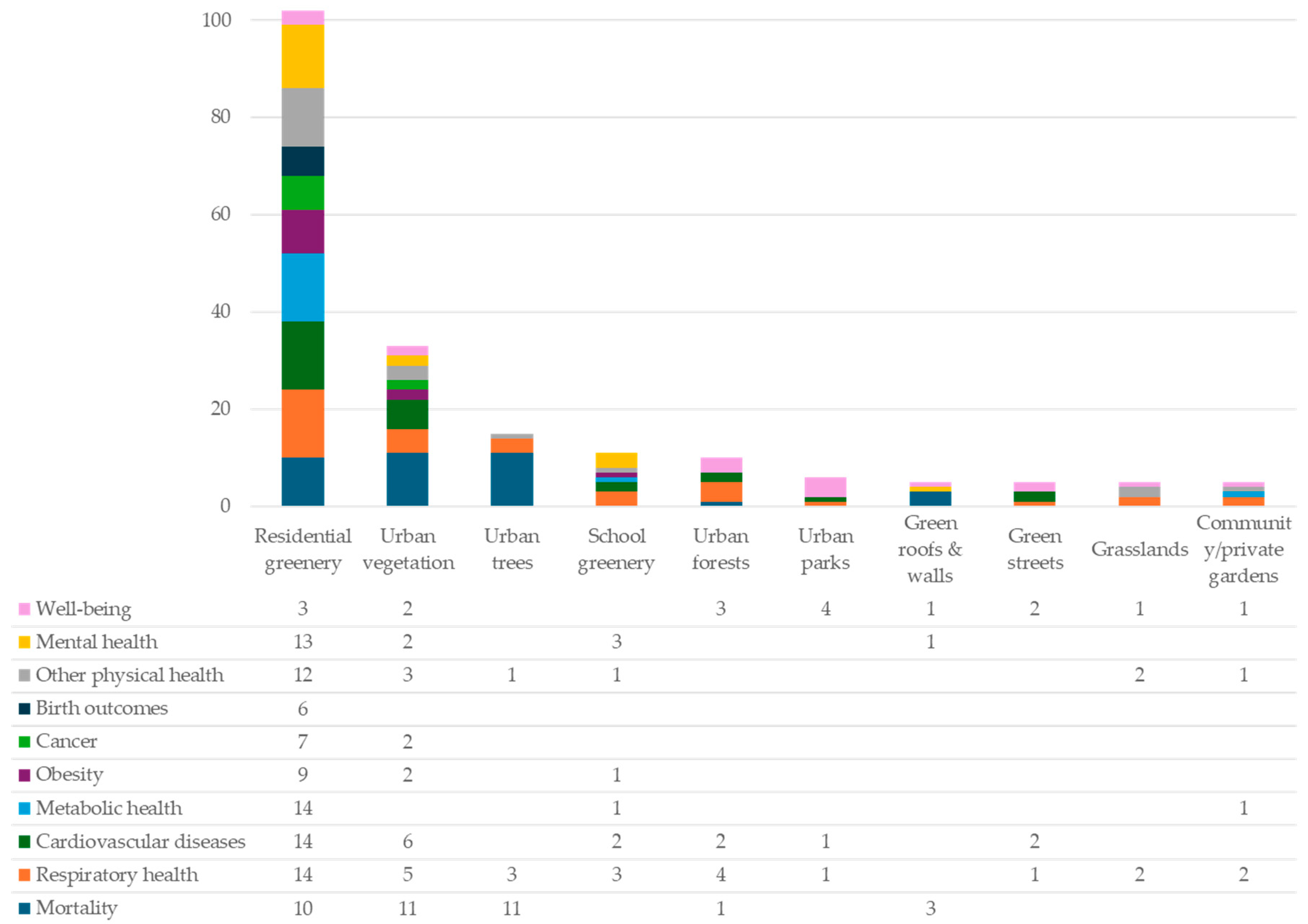

3.3. The Evidence of Climate Adaptation with Health Co-Benefits Across UGI Types

3.3.1. Residential Greenery

3.3.2. Urban Vegetation

3.3.3. Urban Trees

3.3.4. School Greenery

3.3.5. Urban Forests

3.3.6. Urban Parks

3.3.7. Green Roofs and Green Walls

3.3.8. Green Streets

3.3.9. Grasslands

3.3.10. Community or Private Gardens

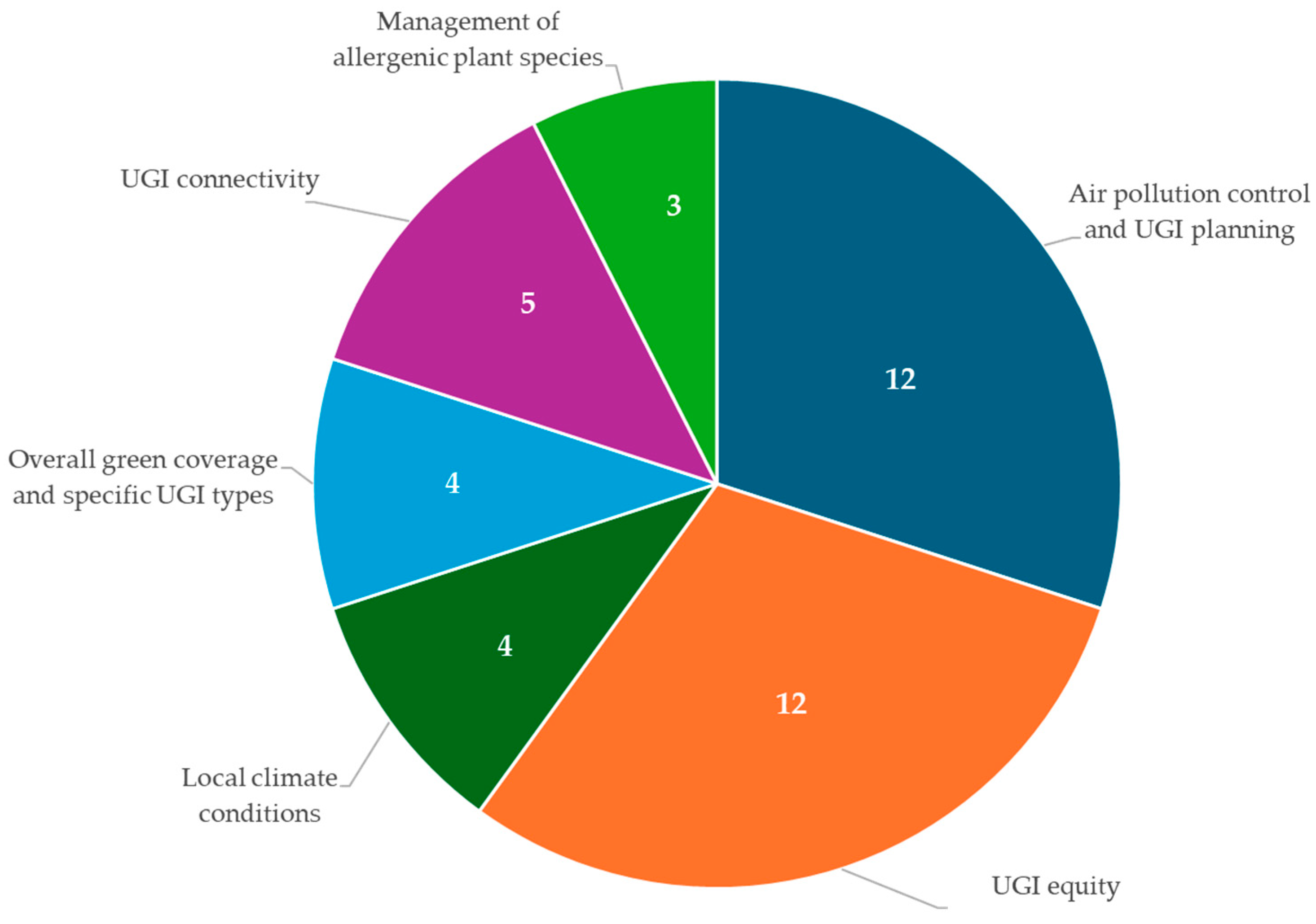

4. Policy Evidence and Implications for Urban Policy and Spatial Planning

- Residential greenery and urban vegetation can reduce air-pollution-related mortality and cardiovascular disease in younger individuals and women [38,40], and they can lower heat-related mortality in older adults [44,150]; however, benefits diminish in highly polluted areas [71,91,163], depend on the scale and density of urban areas [62,155], and may exacerbate allergenic reactions in children [69,157].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, Q. Integrating green infrastructure, ecosystem services and nature-based solutions for urban sustainability: A comprehensive literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesoji, T.; Pearce, A. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Green Infrastructure: A Systematic Exploration of Definitions and Their Origins. Environments 2024, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsler, A.M.; Meerow, S.; Mell, I.C.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A. A ‘green’ chameleon: Exploring the many disciplinary definitions, goals, and forms of “green infrastructure”. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washbourne, C.-L. Environmental policy narratives and urban green infrastructure: Reflections from five major cities in South Africa and the UK. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 129, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I.; Clement, S. Progressing Green Infrastructure planning: Understanding its scalar, temporal, geo-spatial and disciplinary evolution. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2020, 38, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, H. Understanding green infrastructure: The development of a contested concept in England. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimentor, A.; Apostolopoulou, E.; Mazaris, A.D. A review of green infrastructure research in Europe: Challenges and opportunities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Berry, P.; Smith, A. The climate benefits, co-benefits, and trade-offs of green infrastructure: A systematic literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 291, 112583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, C. Urban Greenspace, Climate Adaptation and Health Co-Benefits: Municipal Policy and Practice in London. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardo, L.; Geneletti, D.; Pérez-Soba, M.; Van Eupen, M. Estimating the cooling capacity of green infrastructures to support urban planning. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckart, K.; McPhee, Z.; Bolisetti, T. Performance and implementation of low impact development—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607–608, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maragno, D.; Gaglio, M.; Robbi, M.; Appiotti, F.; Fano, E.A.; Gissi, E. Fine-scale analysis of urban flooding reduction from green infrastructure: An ecosystem services approach for the management of water flows. Ecol. Model. 2018, 386, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, V.; Gough, W.A. Evaluating the potential of nature-based solutions to reduce ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon dioxide through a multi-type green infrastructure study in Ontario, Canada. City Environ. Interact. 2020, 6, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Reid, C.E.; Fuller, C.H. Green infrastructure can limit but not solve air pollution injustice. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Green Infrastructure and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.J.; Rahaman, M.; Hossain, S.I. Urban green spaces for elderly human health: A planning model for healthy city living. Land Use Pol. 2022, 114, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, M. Climate change, health and green space co-benefits. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can.-Res. Policy Pract. 2019, 39, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Liu, R.; Ji, M.; An, R. The Influence of Green Space on Obesity in China: A Systematic Review. Obes. Facts 2022, 15, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Esnaola, M.; Forns, J.; Basagaña, X.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Rivas, I.; López-Vicente, M.; De Castro Pascual, M.; Su, J.; et al. Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7937–7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mavoa, S.; Zhao, J.; Raphael, D.; Smith, M. The Association between Green Space and Adolescents’ Mental Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belesova, K.; Callaghan, M.; Minx, J.C.; Creutzig, F.; Turcu, C.; Hutchinson, E.; Milner, J.; Crane, M.; Haines, A.; Davies, M.; et al. Climate action for health and wellbeing in cities: A protocol for the systematic development of a database of peer-reviewed studies using machine learning methods. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Belesova, K.; Crane, M.; Hale, J.; Haines, A.; Hutchinson, E.; Kiesewetter, G.; Mberu, B.; Mohajeri, N.; Michie, S.; et al. The CUSSH programme: Supporting cities’ transformational change towards health and sustainability. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, A. Health co-benefits of climate action. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e4–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, A. Co-benefits and synergies between urban climate change mitigation and adaptation measures: A literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, A.; Berge, E. How to do a systematic review. Int. J. Stroke 2018, 13, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Moldavska, A.; Welo, T. The concept of sustainable manufacturing and its definitions: A content-analysis based literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Chang, J.; Syrbe, R.-U. Green Infrastructure Planning in Germany and China: A comparative approach to green space policy and planning structure. Res. Urban. Ser. 2020, 6, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chu, Q.; Wang, H.; Tang, Y. Policy Intervention on Green Infrastructure in Chinese Cities. In Green Infrastructure in Chinese Cities; Cheshmehzangi, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 21–53. ISBN 978-981-16-9174-4. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataramanan, V.; Packman, A.I.; Peters, D.R.; Lopez, D.; McCuskey, D.J.; McDonald, R.I.; Miller, W.M.; Young, S.L. A systematic review of the human health and social well-being outcomes of green infrastructure for stormwater and flood management. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 246, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.; Clay, G.; Morrison, R.; Payne, S.; Gilchrist, A.; Rothwell, J.J.; Tantanasi, I. Understanding Green Infrastructure: A Signposting Guide. (NERC Project NE/N017498/1.). University of Manchester. 2019. Available online: https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/publications/understanding-green-infrastructure-a-signposting-guide/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Korkou, M.; Tarigan, A.K.M.; Hanslin, H.M. The multifunctionality concept in urban green infrastructure planning: A systematic literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 85, 127975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereziartua, A.; Chen, J.; de Hoogh, K.; Rodopoulou, S.; Andersen, Z.J.; Bellander, T.; Brandt, J.; Fecht, D.; Forastiere, F.; Gulliver, J.; et al. Exposure to surrounding greenness and natural-cause and cause-specific mortality in the ELAPSE pooled cohort. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.S.; Zhu, A.; Lv, Y.; Shi, X. Interaction between residential greenness and air pollution mortality: Analysis of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e107–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klompmaker, J.O.; Janssen, N.A.H.; Bloemsma, L.D.; Marra, M.; Lebret, E.; Gehring, U.; Hoek, G. Effects of exposure to surrounding green, air pollution and traffic noise with non-accidental and cause-specific mortality in the Dutch national cohort. Environ. Health 2021, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienneau, D.; de Hoogh, K.; Faeh, D.; Kaufmann, M.; Wunderli, J.M.; Röösli, M. More than clean air and tranquillity: Residential green is independently associated with decreasing mortality. Environ. Int. 2017, 108, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Pretty, J.; Roscoe, C.; James, P.; Ji, J.S. Greenspace and mortality in the U.K. Biobank: Longitudinal cohort analysis of socio-economic, environmental, and biomarker pathways. SSM—Popul. Health 2022, 19, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhou, P.; Peng, M.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; et al. Residential greenness mitigates mortality risk from short-term airborne particulate exposure: An individual-level case-crossover study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orioli, R.; Antonucci, C.; Scortichini, M.; Cerza, F.; Marando, F.; Ancona, C.; Manes, F.; Davoli, M.; Michelozzi, P.; Forastiere, F.; et al. Exposure to Residential Greenness as a Predictor of Cause-Specific Mortality and Stroke Incidence in the Rome Longitudinal Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 027002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscoe, C.; Mackay, C.; Gulliver, J.; Hodgson, S.; Cai, Y.; Vineis, P.; Fecht, D. Associations of private residential gardens versus other greenspace types with cardiovascular and respiratory disease mortality: Observational evidence from UK Biobank. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Xu, R.; Lu, P.; Dong, X.; Ma, W.; Hu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; et al. Moderating effect of green space on relationship between atmospheric particulate matter and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease mortality in Ningxia, China. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 120931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, C.; Ji, J.S.; Bell, M.L. Effect modification of greenness on temperature-mortality relationship among older adults: A case-crossover study in China. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellaneda-Gómez, C.; Vivanco-Hidalgo, R.M.; Olmos, S.; Lazcano, U.; Valentin, A.; Milà, C.; Ambrós, A.; Roquer, J.; Tonne, C. Air pollution and surrounding greenness in relation to ischemic stroke: A population-based cohort study. Environ. Int. 2022, 161, 107147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Yu, Y.; Liu, C.; Tang, L.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, P.; He, F.; Wang, M.; Shi, C.; Lu, Z.; et al. Effect of neighbourhood greenness on the association between air pollution and risk of stroke first onset: A case-crossover study in shandong province, China. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 254, 114262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.-W.; Jiang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, B.; Chen, G.; Pu, Y.; Ma, H.; Liang, J.; Xiao, X.; Guo, Y.; et al. Urban greenspaces and child blood pressure in China: Evidence from a large population-based cohort study. Environ. Res. 2024, 244, 117943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Xiao, T.; Grekousis, G.; Zhao, H.; He, J.; Dong, G.; Liu, Y. Greenness-air pollution-physical activity-hypertension association among middle-aged and older adults: Evidence from urban and rural China. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, M.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Xu, Q. Residential greenness attenuated association of long-term air pollution exposure with elevated blood pressure: Findings from polluted areas in Northern China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1019965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Pan, C.; Yan, M.; Wang, Z.; He, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Effects of PM2.5 components on hypertension and diabetes: Assessing the mitigating influence of green spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 959, 178219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, J.-W.; Wu, C.; Chan, C.-C. The association of hypertension and prehypertension with greenness and PM2.5 in urban environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-B.; Hou, Z.-H.; Huang, C.-H.; LaMonte, M.J.; Wang, M.; Lu, B. Associations of exposure to residential green space and neighborhood walkability with coronary atherosclerosis in Chinese adults. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, X.; Zhang, L.; Kan, H.; Chen, R. Association of residential greenness with incident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. Environ. Int. 2023, 171, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, D.W.; Yeager, R.; Conklin, D.J.; DeJarnett, N.; Keith, R.J.; DeFilippis, A.P.; Rai, S.N.; Bhatnagar, A. Residential proximity to greenness mitigates the hemodynamic effects of ambient air pollution. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H1102–H1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Wang, W.; Wei, N.; Liu, L.; Yi, W.; Song, J.; Cheng, J.; Su, H.; Fan, Y. Does the morphology of residential greenspaces contribute to the development of a cardiovascular-healthy city? Environ. Res. 2024, 257, 119280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Yu, Z.; Xu, L.; Wu, Y.; Yu, L.; Yang, Z.; Shen, P.; Lin, H.; Shui, L.; Tang, M.; et al. Residential greenness, air pollution, and incident ischemic heart disease: A prospective cohort study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, J.; Cao, Z.; Huang, C.; Lei, L.; Yang, Y.; Peng, J.; Shi, X. Modification effect of urban landscape characteristics on the association between heat and stroke morbidity: A small-scale intra-urban study in Shenzhen, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, F.F.; Lin, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Modification of low temperature-related hospital admissions for cardiovascular diseases by multiple green space indicators at multiple spatial scales: Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 251, 114193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Sarkar, C.; Kumari, S.; James, P.; Cao, W.; Lee, R.S.; Tian, L.; Webster, C. Air pollution associated respiratory mortality risk alleviated by residential greenness in the Chinese Elderly Health Service Cohort. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, I.; White, M.; Cherrie, M.; Wheeler, B.; Taylor, J.; McInnes, R.; Otte im Kampe, E.; Vardoulakis, S.; Sarran, C.; Soyiri, I.; et al. Land cover and air pollution are associated with asthma hospitalisations: A cross-sectional study. Environ. Int. 2017, 109, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Tan, J.; Yu, G.; Yan, C.; Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Tong, S. Higher greenspace exposure is associated with a decreased risk of childhood asthma in Shanghai—A megacity in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 256, 114868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ahn, Y. The Contribution of Neighborhood Tree and Greenspace to Asthma Emergency Room Visits: An Application of Advanced Spatial Data in Los Angeles County. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.-P.; Chen, G.; Wen, Y.; Heinrich, J.; Fuertes, E.; Zhao, T.; Idrose, N.S.; Lin, L.-Z.; Gui, Z.-H.; Qin, X.; et al. Greenspace and respiratory diseases and symptoms in Chinese children: A large-scale study exploring joint associations with ozone. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 124, 106329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Marcon, A.; Bertelsen, R.J.; Benediktsdottir, B.; Brandt, J.; Frohn, L.M.; Geels, C.; Gislason, T.; Heinrich, J.; Holm, M.; et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and greenness in association with respiratory emergency room visits and hospitalizations: The Life-GAP project. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 120938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasceno da Silva, R.M.; Castelhano, F.J.; Albino Sitoe, G.A.; Hoinaski, L.; Amini, H.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; Requia, W.J. The mediating role of air pollution in the relationship between greenspace and cardiorespiratory admissions in Brazil. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 369, 125849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liu, Z.; La, Y.; Feng, C.; Yu, B.; Wang, Q.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Feng, Y.; Ciren, L.; et al. Associations between residential greenness and the predicted 10-year risk for atherosclerosis cardiovascular disease among Chinese adults. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 868, 161643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuertes, E.; Markevych, I.; Thomas, R.; Boyd, A.; Granell, R.; Mahmoud, O.; Heinrich, J.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Roda, C.; Henderson, J.; et al. Residential greenspace and lung function up to 24 years of age: The ALSPAC birth cohort. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Xie, B.; Liu, K.; Chen, B. Exploring the interactive effects of greenspace morphology and air pollutant on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: A comparative analysis between urban and rural areas in China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 104, 128676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-J.; Yu, P.-Y.; Tai, C.-J.; Jan, R.-H.; Wen, T.-H.; Lin, S.-W.; Tseng, C.-C. Association between the First Occurrence of Asthma and Residential Greenness in Children and Teenagers in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, H.; Zheng, T. Association between Green Space Structure and the Prevalence of Asthma: A Case Study of Toronto. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Norbäck, D.; Cai, Y.S.; Zhang, X. Exposure to greenness, air pollution and respiratory health among pre-school children in northern China. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 298, 119608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevych, I.; Zhao, T.; Fuertes, E.; Marcon, A.; Dadvand, P.; Vienneau, D.; Garcia Aymerich, J.; Nowak, D.; de Hoogh, K.; Jarvis, D.; et al. Residential greenspace and lung function decline over 20 years in a prospective cohort: The ECRHS study. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.J.; Walters, E.H.; Perret, J.L.; Burgess, J.A.; Johns, D.P.; Lowe, A.J.; Lodge, C.J.; Rezvan, P.H.; Simpson, J.A.; Morrison, S.; et al. Clinical and functional differences between early-onset and late-onset adult asthma: A population-based Tasmanian Longitudinal Health Study. Thorax 2016, 71, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbihi, H.; Koehoorn, M.; Tamburic, L.; Brauer, M. Asthma Trajectories in a Population-based Birth Cohort. Impacts of Air Pollution and Greenness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; Pan, R.; Liu, J.; Yi, W.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Kuang, L.; Liu, L.; Wei, N.; et al. Green space and its types can attenuate the associations of PM2.5 and its components with prediabetes and diabetes—A multicenter cross-sectional study from eastern China. Environ. Res. 2024, 245, 117997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiering, E.; Markevych, I.; Brüske, I.; Fuertes, E.; Kratzsch, J.; Sugiri, D.; Hoffmann, B.; von Berg, A.; Bauer, C.-P.; Koletzko, S.; et al. Associations of Residential Long-Term Air Pollution Exposures and Satellite-Derived Greenness with Insulin Resistance in German Adolescents. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Gu, T.; Xu, Z.; He, T.; Li, G.; Huang, J. Associations of residential green space with incident type 2 diabetes and the role of air pollution: A prospective analysis in UK Biobank. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Ye, T.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Cheng, J.; Shen, Y.; et al. Urban overall and visible greenness and diabetes among older adults in China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 240, 104881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, S.; Hu, K.; Xia, W. Effect of residential exposure to green space on maternal blood glucose levels, impaired glucose tolerance, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Chang, H.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Huang, C. Green space, air pollution and gestational diabetes mellitus: A retrospective cohort study in central China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Jiang, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Cao, J.; Qiu, W.; Huang, R.; Zhang, J.; Ye, W.; Zhang, Q. The influence of socioeconomic status on the association between residential greenness and gestational diabetes mellitus in an urban setting: A multicenter study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yan, L.L.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Huang, C.; Kan, H.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Shi, X.; et al. Air pollution, residential greenness, and metabolic dysfunction biomarkers: Analyses in the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoin, K.; Pharino, C.; Vathesatogkit, P.; Phosri, A.; Buya, S.; Ueda, K.; Seposo, X.T.; Ingviya, T.; Saranburut, K.; Thongmung, N.; et al. Associations between residential greenness and air pollution and the incident metabolic syndrome in a Thai worker cohort. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, C.; Lei, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Tian, H.; Xue, B.; Zhou, E.; Zhang, K.; Hu, J.; et al. Associations of PM2.5 composition and green space with metabolic syndrome in a Chinese essential hypertensive population. Chemosphere 2023, 343, 140243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odebeatu, C.C.; Darssan, D.; Roscoe, C.; Reid, S.; Osborne, N.J. Residential greenspace indicators and metabolic syndrome in the UK Biobank Cohort: Mediation through behavioural, environmental, social and biomarker pathways. Environ. Res. 2025, 283, 122148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Jia, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, G.; Ciren, Z.; Chen, H.; Duoji, Z.; Xu, J.; Yang, T.; Xu, H.; et al. Residential greenness associated with decreased risk of metabolic- dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: Evidence from a large population-based epidemiological study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yang, S.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, P.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, X. Residential green and blue spaces with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease incidence: Mediating effect of air pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres Toda, M.; Miri, M.; Heydari, H.; Lari Najafi, M.; Gómez-Roig, M.D.; Llurba, E.; Foraster, M.; Dadvand, P. A study on exposure to greenspace during pregnancy and lipid profile in cord blood samples. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ryck, E.; Ghosh, M.; Nawrot, T.S.; Reimann, B.; Koppen, G.; Verachtert, E.; Devlieger, R.; Godderis, L.; Pauwels, S. Effects of exposure to environmental factors on obesity-related growth parameters and leptin (LEP) methylation in children. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 346, 123465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-Z.; Yang, B.-Y.; Yu, H.-Y.; Bloom, M.S.; Markevych, I.; Heinrich, J.; Knibbs, L.D.; Leskinen, A.; Dharmage, S.C.; Jalaludin, B.; et al. Association between community greenness and obesity in urban-dwelling Chinese adults. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 135040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemsma, L.D.; Wijga, A.H.; Klompmaker, J.O.; Janssen, N.A.H.; Smit, H.A.; Koppelman, G.H.; Brunekreef, B.; Lebret, E.; Hoek, G.; Gehring, U. The associations of air pollution, traffic noise and green space with overweight throughout childhood: The PIAMA birth cohort study. Environ. Res. 2019, 169, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan-Gordo, C.; Espinosa, A.; Valentin, A.; Tonne, C.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Castaño-Vinyals, G.; Dierssen-Sotos, T.; Moreno-Iribas, C.; de Sanjose, S.; Fernandez-Tardón, G.; et al. Green spaces, excess weight and obesity in Spain. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 223, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, R.; Knibbs, L.D.; Jalaludin, B.; Heinrich, J.; Markevych, I.; Gao, M.; Xu, S.-L.; Wu, Q.-Z.; Zeng, X.-W.; et al. Street view greenness is associated with lower risk of obesity in adults: Findings from the 33 Chinese community health study. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, Å.; Pyko, A.; Lind, T.; Bellander, T.; Östenson, C.-G.; Pershagen, G.; Eriksson, C.; Lõhmus, M. Urban residential greenness and adiposity: A cohort study in Stockholm County. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Thi Khanh, H.; Rigau-Sabadell, M.; Khomenko, S.; Pereira Barboza, E.; Cirach, M.; Duarte-Salles, T.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Mueller, N.; de Bont, J. Ambient air pollution, urban green space and childhood overweight and obesity: A health impact assessment for Barcelona, Spain. Environ. Res. 2025, 264, 120306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Tang, W.; Fan, Y.; Ma, C.; Ye, T.; Cai, C.; Xie, Y.; Shi, Y.; Baima, K.; Yang, T.; et al. Associations between residential greenness and obesity phenotypes among adults in Southwest China. Health Place 2024, 87, 103236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Guo, Y.; Bao, Z.; Lin, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, G.; Li, Q.; Bao, H.; Ji, Y.; Luo, S.; et al. Individual and joint effects of prenatal green spaces, PM2.5 and PM1 exposure on BMI Z-score of children aged two years: A birth cohort study. Environ. Res. 2022, 205, 112548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Loureiro, L.; Verdoodt, F.; Lefebvre, W.; Vanpoucke, C.; Casas, L.; Gadeyne, S. Long-term exposure to residential green spaces and site-specific cancer mortality in urban Belgium: A 13-year follow-up cohort study. Environ. Int. 2022, 170, 107571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-J.; Lee, P.-H.; Chen, L.-C.; Lin, B.-C.; Lin, C.; Chan, T.-C. Relationships among green space, ambient fine particulate matter, and cancer incidence in Taiwan: A 16-year retrospective cohort study. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wu, G.; Wei, J.; Lawrence, W.R.; Deng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Chen, D.; et al. Potential causal links and mediation pathway between urban greenness and lung cancer mortality: Result from a large cohort (2009 to 2020). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Iyer, H.S.; Lu, Y.; Laden, F.; Song, M.; Roscoe, C. Neighborhood socioeconomic disparities in cancer incidence following a hypothetical intervention to increase residential greenspace cover in the UK Biobank cohort. Environ. Res. 2025, 266, 120387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odebeatu, C.C.; Darssan, D.; Roscoe, C.; Ahmed, M.; Reid, S.; Osborne, N.J. Greenspace and risk of obesity-related cancer in the UK Biobank cohort: An analysis of private residential gardens and other greenspace types. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 943, 173833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan-Gordo, C.; Kogevinas, M.; Cirach, M.; Castaño-Vinyals, G.; Aragonés, N.; Delfrade, J.; Fernández-Villa, T.; Amiano, P.; Dierssen-Sotos, T.; Tardon, A.; et al. Residential proximity to green spaces and breast cancer risk: The multicase-control study in Spain (MCC-Spain). Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datzmann, T.; Markevych, I.; Trautmann, F.; Heinrich, J.; Schmitt, J.; Tesch, F. Outdoor air pollution, green space, and cancer incidence in Saxony: A semi-individual cohort study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sheridan, P.; Laurent, O.; Li, J.; Sacks, D.A.; Fischer, H.; Qiu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yim, I.S.; Jiang, L.-H.; et al. Associations between green space and preterm birth: Windows of susceptibility and interaction with air pollution. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lin, H.; Liu, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Byun, H.-M.; Li, P.; Li, C.; et al. Association of residential greenness, air pollution with adverse birth outcomes: Results from 61,762 mother-neonatal pairs in project ELEFANT (2011–2021). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaraci, S.; Feng, X.; Suesse, T.; Jalaludin, B.; Astell-Burt, T. Associations between green space, air pollution and birthweight in Sydney Metropolitan Area, Australia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 76, 127726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Hu, Y.; Ma, W.; Li, N.; Chang, J.; Wang, Y. Sensitive months for green spaces’ impact on macrosomia and interaction with air pollutants: A birth cohort study. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 368, 125743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Lamichhane, D.K.; Lee, M.; Ye, S.; Kwon, J.-H.; Park, M.-S.; Kim, H.-C.; Leem, J.-H.; Hong, Y.-C.; Kim, Y.; et al. Preventive Effect of Residential Green Space on Infantile Atopic Dermatitis Associated with Prenatal Air Pollution Exposure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Luo, X.; Cao, G.; Zhao, C.; Xiao, J.; Liu, X.; Dong, M.; Wang, J.; Zeng, W.; Guo, L.; et al. Associations of ambient temperature exposure during pregnancy with the risk of miscarriage and the modification effects of greenness in Guangdong, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Que, Q.; Tu, R.; Liu, Y.; Gao, W. How do landscape elements affect public health in subtropical high-density city: The pathway through the neighborhood physical environmental factors. Build. Environ. 2021, 206, 108336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Yao, Z.; Pearce, J.R.; Feng, Z.; James Browne, A.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Y. Non-linear association between residential greenness and general health among old adults in China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 223, 104406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wei, F.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Lin, H.; Shui, L.; Jin, M.; Wang, J.; Tang, M.; Chen, K. Air pollution, surrounding green, road proximity and Parkinson’s disease: A prospective cohort study. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yu, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, P.; Lin, H.; Shui, L.; Tang, M.; et al. Residential greenness, air pollution and incident neurodegenerative disease: A cohort study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, M.; Hao, X.; Ma, D.; Guo, M.; Zuo, C.; Li, S.; Liang, Y.; Hao, C.; Wang, Z.; et al. Air pollution, greenspace exposure and risk of Parkinson’s disease: A prospective study of 441,462 participants. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 5233–5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Kang Zhuo, B.M.; Guo, B.; Zeng, P.-B.; Guo, Y.-M.; Chen, G.-B.; Wei, J.; He, R.-F.; Li, Z.-F.; Zhang, X.-H.; et al. Living near greenness is associated with higher bone strength: A large cross-sectional epidemiological study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 155393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Tao, L. Association of residential green space with risk of sarcopenia and the role of air pollution: Evidence from UK Biobank. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 370, 125857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.-W.; Zhao, Y.; Dadvand, P.; Jiang, N.; Chen, G.; Yang, B.; Huang, W.; Xiao, X.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Urban greenspace and visual acuity in schoolchildren: A large prospective cohort study in China. Environ. Int. 2024, 184, 108423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Su, W.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Meng, J.; Ahmed, M.A.; Qu, G.; Sun, Y. Assessing the effects of air pollution and residential greenness on frailty in older adults: A prospective cohort study from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 9091–9105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wang, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Li, P.; Ma, L.; Wei, F.; Chen, R.; Liang, C.; et al. Residential greenness and prevalence of chronic kidney disease: Findings from the China National Survey of Chronic Kidney Disease. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Liu, M.; He, P.; Wu, Q.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gan, X.; Sun, J.; et al. Various ambient air pollutants, residential green spaces, fibrosis 4 scores, genetic susceptibility, and risk of severe liver disease. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 263, 115246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, B.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, P.; Tian, M.; Lu, Z.; Guo, X.; Jia, X. Association of ambient ozone exposure and greenness exposure with hemorrhagic stroke mortality at different times: A cohort study in Shandong Province, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuchi, W.; Brauer, M.; Czekajlo, A.; Davies, H.W.; Davis, Z.; Guhn, M.; Jarvis, I.; Jerrett, M.; Nesbitt, L.; Oberlander, T.F.; et al. Neighborhood environmental exposures and incidence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A population-based cohort study. Environ. Int. 2022, 161, 107120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asta, F.; Michelozzi, P.; Cesaroni, G.; De Sario, M.; Davoli, M.; Porta, D. Green spaces and cognitive development at age 7 years in a rome birth cohort: The mediating role of nitrogen dioxide. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zhang, B.; Xia, W.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, S.; Hu, K.; Xu, S.; Li, Y. Residential exposure to green space and early childhood neurodevelopment. Environ. Int. 2019, 128, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagalan, L.; Oberlander, T.F.; Hanley, G.E.; Rosella, L.C.; Bickford, C.; Weikum, W.; Lanphear, N.; Lanphear, B.; Brauer, M.; van den Bosch, M. The association between prenatal greenspace exposure and Autism spectrum disorder, and the potentially mediating role of air pollution reduction: A population-based birth cohort study. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhtsiyarava, M.; Ju, Y.; Moran, M.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Dronova, I.; Delclòs-Alió, X.; Moore, K.; Castillo-Riquelme, M.; Anza-Ramirez, C. Associations between urban greenspace and depressive symptoms in Mexico’s cities using different greenspace metrics. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 164, 103219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Zhang, G.; Cao, Y. Green Space for Mental Health in the COVID-19 Era: A Pathway Analysis in Residential Green Space Users. Land 2022, 11, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoc, I.; Ginos, B.N.R.; Goncalves Soares, A.; Elhakeem, A.; Voortman, T.; Kavousi, M.; Luik, A.I.; Roseboom, T.J.; De Rooij, S.R. Examining associations of air pollution and green space with depressive symptoms in adults: A LongITools cross-cohort analysis. Environ. Res. 2025, 264, 120321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouly, T.A.; Mishra, G.D.; Hystad, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Knibbs, L.D. Residential greenspace and anxiety symptoms among Australian women living in major cities: A longitudinal analysis. Environ. Int. 2023, 179, 108110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebner, K.; Markevych, I.; Bertelsen, R.J.; Sved Skottvoll, B.; Hustad, S.; Forsberg, B.; Franklin, K.A.; Holm, M.; Lindberg, E.; Heinrich, J.; et al. Lifelong exposure to residential greenspace and the premenstrual syndrome: A population-based study of Northern European women. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, E.; Zhao, J.; Ye, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, D.; Shao, J.; Li, X.; Ye, Z. Green sanctuaries: Residential green and garden space and the natural environment mitigate mental disorders risk of diabetic patients. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Liao, J.; Wang, X.; Jiao, K.; Ma, X.; Liao, J.; Liu, X.; Ma, L. Association of NO2 with daily hospital admissions for mental disorders: Investigation of the modification effects of green spaces and long-term NO2 exposure. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 156, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Hart, J.E.; Roscoe, C.; Mehta, U.V.; Pescador Jimenez, M.; Lin, P.-I.D.; Suel, E.; Hystad, P.; Hankey, S.; Zhang, W.; et al. Greenspace and depression incidence in the US-based nationwide Nurses’ Health Study II: A deep learning analysis of street-view imagery. Environ. Int. 2025, 198, 109429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Tian, M.; Yuan, L. Do objective and subjective traffic-related pollution, physical activity and nature exposure affect mental wellbeing? Evidence from Shenzhen, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, T.; Wu, W. Can multiple pathways link urban residential greenspace to subjective well-being among middle-aged and older Chinese adults? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 223, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Feng, Z.; Pearce, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, G. Are greenspace quantity and quality associated with mental health through different mechanisms in Guangzhou, China: A comparison study using street view data. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 290, 117976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.M.; Lee, W.; Roye, D.; Heo, S.; Urban, A.; Entezari, A.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Zanobetti, A.; Gasparrini, A.; Analitis, A.; et al. Effect modification of greenness on the association between heat and mortality: A multi-city multi-country study. eBioMedicine 2022, 84, 104251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-C.; Du, Z.-C.; Fan, S.-J.; Mute Browning, M.H.E.; Knibbs, L.D.; Bloom, M.S.; Zhao, T.-Y.; Jalaludin, B.; Heinrich, J.; Liu, X.-X.; et al. Association between long-term green space exposure and mortality in China: A difference-in-differences analysis of national data in 2000, 2010 and 2019. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 887, 164023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.N.; Van, D.Q.; Kusaka, H.; Seposo, X.T.; Honda, Y. Green Space and Deaths Attributable to the Urban Heat Island Effect in Ho Chi Minh City. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, S137–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkart, K.; Meier, F.; Schneider, A.; Breitner, S.; Canário, P.; Alcoforado, M.J.; Scherer, D.; Endlicher, W. Modification of Heat-Related Mortality in an Elderly Urban Population by Vegetation (Urban Green) and Proximity to Water (Urban Blue): Evidence from Lisbon, Portugal. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, J.-Y.; Lane, K.J.; Lee, J.-T.; Bell, M.L. Urban vegetation and heat-related mortality in Seoul, Korea. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, M.; Goria, S.; Wagner, V.; Sabastia, M.; Guillet, A.; Cordeau, E.; Mauclair, C.; Host, S. Greening is a promising but likely insufficient adaptation strategy to limit the health impacts of extreme heat. Environ. Int. 2021, 151, 106441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkstein, L.S.; Eisenman, D.P.; de Guzman, E.B.; Sailor, D.J. Increasing trees and high-albedo surfaces decreases heat impacts and mortality in Los Angeles, CA. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinasi, L.H.; Bakhtsiyarava, M.; Sanchez, B.N.; Kephart, J.L.; Ju, Y.; Arunachalam, S.; Gouveia, N.; Teixeira Caiaffa, W.; O’Neill, M.S.; Dronova, I.; et al. Greenness and excess deaths from heat in 323 Latin American cities: Do associations vary according to climate zone or green space configuration? Environ. Int. 2023, 180, 108230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Gasparrini, A.; Wei, D.; Lu, Y.; Hu, K.; Fischer, T.B.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Do greenspaces really reduce heat health impacts? Evidence for different vegetation types and distance-based greenspace exposure. Environ. Int. 2024, 191, 108950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Keijzer, C.; Agis, D.; Ambrós, A.; Arévalo, G.; Baldasano, J.M.; Bande, S.; Barrera-Gómez, J.; Benach, J.; Cirach, M.; Dadvand, P.; et al. The association of air pollution and greenness with mortality and life expectancy in Spain: A small-area study. Environ. Int. 2017, 99, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, P.; Liu, T.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, J. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of PM2.5-Related Premature Deaths and the Role of Greening Improvement in Sustainable Urban Health Governance. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ma, X.; Geng, Y.; Liao, J.; Ma, L. Association between smoking and hypertension under different PM2.5 and green space exposure: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1026648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, R.; Kadier, A.; Wang, W.; Zhou, F.; Ling, L. Combined effects of heatwaves and air pollution, green space and blue space on the incidence of hypertension: A national cohort study. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Bell, M.L. The influence of green space on the short-term effects of particulate matter on hospitalization in the U.S. for 2000–2013. Environ. Res. 2019, 174, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, W.; Wen, H.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiao, K.; Chen, Q.; Feng, H.; Wang, Y.; Liao, J.; et al. Effects of green spaces on alleviating mortality attributable to PM2.5 in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 14402–14412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-S.; Lung, S.-C.C. Can green structure reduce the mortality of cardiovascular diseases? Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566–567, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Chen, C.; Kim, H.; Sabath, B.; Dominici, F.; Warren, J.L.; Di, Q.; Schwartz, J.; Bell, M.L. Temporal changes in associations between high temperature and hospitalizations by greenspace: Analysis in the Medicare population in 40 U.S. northeast counties. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafari, S.; Shabani, A.A.; Moeinaddini, M.; Danehkar, A.; Sakieh, Y. Applying landscape metrics and structural equation modeling to predict the effect of urban green space on air pollution and respiratory mortality in Tehran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meo, S.A.; Almutairi, F.J.; Abukhalaf, A.A.; Usmani, A.M. Effect of Green Space Environment on Air Pollutants PM2.5, PM10, CO, O3, and Incidence and Mortality of SARS-CoV-2 in Highly Green and Less-Green Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamardi, S.; Lambert, K.A.; Praveena, A.S.; Anand, M.P.; Erbas, B. Time Trends of Greenspaces, Air Pollution, and Asthma Prevalence among Children and Adolescents in India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Park, S. The effect of outdoor air pollutants and greenness on allergic rhinitis incidence rates: A cross-sectional study in Seoul, Korea. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, Q.; Kadier, A.; Wang, W.; Zhou, F.; Li, R.; Ling, L. The role of residential greenness levels, green land cover types and diversity in overweight/obesity among older adults: A cohort study. Environ. Res. 2023, 217, 114854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, J.; Lu, H.; Hu, W.; Hu, M.; He, J.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Multiple environmental exposures and obesity in eastern China: An individual exposure evaluation model. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Xie, B.; An, Z.; Wang, L. Spatial and moderating effects of greenspace on the association between air pollution and lung cancer incidence. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 164, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terre-Torras, I.; Recalde, M.; Díaz, Y.; de Bont, J.; Bennett, M.; Aragón, M.; Cirach, M.; O’Callaghan-Gordo, C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Duarte-Salles, T. Air pollution and green spaces in relation to breast cancer risk among pre and postmenopausal women: A mega cohort from Catalonia. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Fu, H.; Zhu, C.; Sun, Y.; Cao, H. Assessing the health risk impacts of urban green spaces on air pollution—Evidence from 31 China’s provinces. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Du, M. Associations between Greenspaces and Individual Health: A Longitudinal Study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Zhang, H.; Han, Y.; Chen, W.; Teng, Y.; Chatzidiakou, L.; Barratt, B.; Jones, R.; Kelly, F.; Zhu, T.; et al. Short-term air pollution and greenness exposures on oxidative stress in urban and peri-urban residents in Beijing: A part of AIRLESS study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-S. Nature-based solutions to address anxiety disorders: A cross-sectional ecological study of green spatial patterns in Taiwan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 365, 117540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.L.; Chen, H.; Chiu, M.Y.-L. Nexus Between Exposure to Natural Outdoor Environments and Cognitive Competence among Older Adults in China. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2025, 115, 1146–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, C. Does pattern matter? Exploring the pathways and effects of urban green space on promoting life satisfaction through reducing air pollution. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Duan, C.; Chen, B.; Wang, H. The socio-economic value of urban green spaces in mitigating waterlogging and enhancing well-being. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 108010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Chaston, T.; Hanigan, I.; de Dear, R.; Santamouris, M.; Jalaludin, B.; Morgan, G.G. The health benefits of greening strategies to cool urban environments—A heat health impact method. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iungman, T.; Cirach, M.; Marando, F.; Barboza, E.P.; Khomenko, S.; Masselot, P.; Quijal-Zamorano, M.; Mueller, N.; Gasparrini, A.; Urquiza, J.; et al. Cooling cities through urban green infrastructure: A health impact assessment of European cities. Lancet 2023, 401, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Simpson, C.; Brousse, O.; Viitanen, A.-K.; Heaviside, C. The potential of urban trees to reduce heat-related mortality in London. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 054004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R.I.; Kroeger, T.; Zhang, P.; Hamel, P. The Value of US Urban Tree Cover for Reducing Heat-Related Health Impacts and Electricity Consumption. Ecosystems 2020, 23, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Biswas, T.; Chakraborty, T.C.; Kroeger, T.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Fargione, J.E. Current inequality and future potential of US urban tree cover for reducing heat-related health impacts. npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Coville, R.C.; Hirabayashi, S.; Lim, B.; Endreny, T.A.; Nowak, D.J. Modeling lives saved from extreme heat by urban tree cover✰. Ecol. Model. 2021, 449, 109553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, S.; de Guzman, E.B.; Eisenman, D.P.; Sailor, D.J.; Parfrey, J.; Kalkstein, L.S. Increasing tree cover and high-albedo surfaces reduces heat-related ER visits in Los Angeles, CA. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 1603–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, D.; Manoli, G.; Lin, B.; Aerts, R.; Yang, J.; Hahs, A.; Richards, D.; Meili, N.; Zhu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Residential tree canopy configuration and mortality in 6 million Swiss adults: A longitudinal study. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e186–e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranken, A.; Bijnens, E.; Horemans, C.; Leclercq, A.; Kestens, W.; Karakaya, G.; Vandenthoren, L.; Trimpeneers, E.; Vanpoucke, C.; Fierens, F.; et al. Association of air pollution and green space with all-cause general practitioner and emergency room visits: A cross-sectional study of young people and adults living in Belgium. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Pascu, I.-S.; Petrea, S.; Leca, S.; Marco, A.D.; Paoletti, E.; Agathokleous, E.; Calatayud, V. Effect of tree canopy cover on air pollution-related mortality in European cities: An integrated approach. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e527–e537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Hanlon, B. Urban green space, respiratory health and rising temperatures: An examination of the complex relationship between green space and adult asthma across racialized neighborhoods in Los Angeles County. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 258, 105320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Yang, B.-Y.; Hu, L.-W.; Markevych, I.; Bloom, M.S.; Dharmage, S.C.; Jalaludin, B.; Knibbs, L.D.; Heinrich, J.; Morawska, L.; et al. Greenness around schools associated with lower risk of hypertension among children: Findings from the Seven Northeastern Cities Study in China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Qian, Z.; Knibbs, L.D.; Jalaludin, B.; Schootman, M.; McMillin, S.E.; Howard, S.W.; Lin, L.-Z.; et al. Associations between trees and grass presence with childhood asthma prevalence using deep learning image segmentation and a novel green view index. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 286, 117582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-X.; Fan, S.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.-X.; Bao, W.-W.; Guo, Y.; Hu, L.-W.; Chen, G.; Zeng, X.-W.; Zou, Z.; et al. Associations between greenspace surrounding schools and lipid levels in Chinese children and teenagers. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.-W.; Yang, B.-Y.; Zou, Z.-Y.; Ma, J.; Jing, J.; Wang, H.-J.; Luo, J.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Luo, C.-Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Greenness surrounding schools and adiposity in children and adolescents: Findings from a national population-based study in China. Environ. Res. 2021, 192, 110289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requia, W.J.; Saenger, C.C.; Cicerelli, R.E.; de Abreu, L.M.; Cruvinel, V.R.N. Greenness around Brazilian schools may improve students’ math performance but not science performance. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Cai, S.; Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lian, X.; Shi, D.; Chen, Z.; et al. The impact of long-term exposure to NO2, O3, and their oxidative potential on adolescents’ mental health, and the protective role of school-based greenness. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Doyle, M.; McGovern, M.; Pasher, J. Air pollution removal by urban forests in Canada and its effect on air quality and human health. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.d.O.; Favaro, A.; Raimundo-Costa, W.; Anhê, A.C.B.M.; Ferreira, D.C.; Blanes-Vidal, V.; dos Santos Senhuk, A.P.M. Influence of urban forest on traffic air pollution and children respiratory health. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, C.; Choi, S.; Sou, H.-D.; Park, C.-R. Long-Term Greenness Effects of Urban Forests to Reduce PM10 Concentration: Does the Impact Benefit the Population Vulnerable to Asthma? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, R.; Dujardin, S.; Nemery, B.; Van Nieuwenhuyse, A.; Van Orshoven, J.; Aerts, J.-M.; Somers, B.; Hendrickx, M.; Bruffaerts, N.; Bauwelinck, M.; et al. Residential green space and medication sales for childhood asthma: A longitudinal ecological study in Belgium. Environ. Res. 2020, 189, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanki, T.; Siponen, T.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Pennanen, A.; Tiittanen, P.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T.; Tyrväinen, L. Acute effects of visits to urban green environments on cardiovascular physiology in women: A field experiment. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Wang, S.; Fei, F.; Song, J.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Q.; Shen, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; et al. Modifying temperature-related cardiovascular mortality through green-blue space exposure. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 2024, 20, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Qi, J.; Xu, J.; Yi, Y.; Yin, P.; Zhou, M. Forest Mitigates Short-Term Health Risk of Air Pollution: Evidence from China. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 87, 2163–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, K.; Park, Y.M.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Lee, K. Examining the joint effect of air pollution and green spaces on stress levels in South Korea: Using machine learning techniques. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2372321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Z.; Hui, T.; Guo, P. Experiencing urban forests for mitigation of negative emotions of people exposed to seasonal PM2.5 in Northeast China. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 1245–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Xiao, Y.; Tu, R.; Yin, S. Effects of thermal perception on restorative benefits by green space exposure: A pilot study in hot-humid China. Urban Clim. 2024, 53, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, L.; Gao, T. The effect of visibility on green space recovery, perception and preference. Trees For. People 2024, 16, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, B.; Yao, Y.; Wang, C.; Kou, Y.; Xu, S.; Xian, D. A study of subtropical park thermal comfort and its influential factors during summer. J. Therm. Biol. 2022, 109, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Xiong, J.; Qin, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, K.; Yan, J.; Ye, L.; Han, G. Thermal Comfort Influences Positive Emotions but Not Negative Emotions When Visiting Green Spaces during Summer. Forests 2023, 14, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Mao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; Shou, T.; Lu, D.; Geng, W. Exploring the pathways of urban green space exposure on respiratory health: An empirical study in Nanjing, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 101, 128536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvuglia, A.; Koppelaar, R.; Rugani, B. The effect of green roofs on the reduction of mortality due to heatwaves: Results from the application of a spatial microsimulation model to four European cities. Ecol. Model. 2020, 438, 109351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Kinney, P.L.; Ma, W. Potential impacts of cool and green roofs on temperature-related mortality in the Greater Boston region. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 094042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, W.-P.; Liao, M.-C.; Peng, H.-L.; Huang, C.-T.; Chuang, Y.-J.; Wang, J.-J. The Role of Urban Food Forests in Promoting Environmental Sustainability and Public Health: A Focus on Temperature Regulation and Mental Health. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Du, M.; Deng, P.; Zhou, T.; Hong, B. Effects of green walls on thermal perception and cognitive performance: An indoor study. Build. Environ. 2024, 250, 111180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Dong, P.; Dong, G.; Xiao, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, L.; Yu, Y.; Dong, G.-H. Exploring the impacts of street-level greenspace on stroke and cardiovascular diseases in Chinese adults. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 243, 113974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.; Kontokosta, C.E. The impact of urban street tree species on air quality and respiratory illness: A spatial analysis of large-scale, high-resolution urban data. Health Place 2019, 56, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, M.; Liu, B.; Lian, Z.; Xie, J. The influence of urban roadside trees and their physical environment on stress relief measures: A field experiment in Shanghai. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 42, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, W.; Heusinkveld, B.G.; Lenzholzer, S.; van Hove, B. Street greenery and its physical and psychological impact on thermal comfort. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beele, E.; Aerts, R.; Reyniers, M.; Somers, B. Urban green space, human heat perception and sleep quality: A repeated cross-sectional study. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F.; Dotti Sani, G.M.; Giachetta, A.; Perini, K. Nature-Based Solutions: Thermal Comfort Improvement and Psychological Wellbeing, a Case Study in Genoa, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.; Chen, T.-H.; Chung, H.-Y.; Hsiao, H.-Y.; Tseng, P.-C.; Wang, Y.-C.; Candice Lung, S.-C.; Su, H.-J.; Tsay, Y.-S. The health risk reduction of PM2.5 via a green curtain system in Taiwan. Build. Environ. 2024, 255, 111459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tassinary, L.G. Association between greenspace morphology and prevalence of non-communicable diseases mediated by air pollution and physical activity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 242, 104934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I. Global Green Infrastructure: Lessons for Successful Policy-Making, Investment and Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-72096-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, R.; Pauleit, S. From Multifunctionality to Multiple Ecosystem Services? A Conceptual Framework for Multifunctionality in Green Infrastructure Planning for Urban Areas. AMBIO 2014, 43, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige-Elegbede, J.; Pilkington, P.; Bird, E.L.; Gray, S.; Mindell, J.S.; Chang, M.; Stimpson, A.; Gallagher, D.; Petrokofsky, C. Exploring the views of planners and public health practitioners on integrating health evidence into spatial planning in England: A mixed-methods study. J. Public Health 2020, 43, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Carmeliet, J.; Bardhan, R. Cooling efficacy of trees across cities is determined by background climate, urban morphology, and tree trait. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Coutts, A.M.; Livesley, S.J.; Harris, R.J.; Hunter, A.M.; Williams, N.S.G. Planning for cooler cities: A framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukawa, G.Y.; Krecl, P.; Targino, A.C.; Faria, P.C.L.; Batista, L.F.A. Mitigating urban heat stress through green infrastructure: A climate service approach. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janhäll, S. Review on urban vegetation and particle air pollution—Deposition and dispersion. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 105, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwise, Y.; Kumar, P. Designing vegetation barriers for urban air pollution abatement: A practical review for appropriate plant species selection. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jia, Y.; Bai, G.; Han, H.; Yang, W.; Xie, W.; Li, L. Characterizing BVOC emissions of common plant species in northern China using real world measurements: Towards strategic species selection to minimize ozone forming potential of urban greening. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 96, 128341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapriyanto, A.R.; Azmi, H. Implementation of Green Infrastructure in Sustainable Transportation in Supporting Urban Mobility: A Literature Review. Eng. Proc. 2025, 84, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. New Insights into Understanding Urban Traffic Emissions Using Novel Mobile Air Quality Measurements in the Breathe London Pilot Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.M.; Göttsche, F.; Birkmann, J.; Kapp, R.; Schmidt, C.; Weisser, B.; Jamshed, A. Mapping vulnerability to climate change for spatial planning in the region of Stuttgart. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 1573–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Z.J.; McPhearson, T.; Pickett, S.T.A. Transforming US urban green infrastructure planning to address equity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 229, 104591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Monetary valuation of urban nature’s health effects: A systematic review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 1716–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramanan, V.; Lopez, D.; McCuskey, D.J.; Kiefus, D.; McDonald, R.I.; Miller, W.M.; Packman, A.I.; Young, S.L. Knowledge, attitudes, intentions, and behavior related to green infrastructure for flood management: A systematic literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabisch, N.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; Bonn, A. (Eds.) Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice; Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-53750-4. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, T.; Lo, A.Y.; Byrne, J.A. Reconceptualizing green infrastructure for climate change adaptation: Barriers to adoption and drivers for uptake by spatial planners. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evaluation Measure and Indicators | UGI Type |

|---|---|

| NDVI, EVI, green coverage (within 150–1000 m buffers around residences) | Residential greenery |

| NDVI, green coverage (within specific urban area) | Urban vegetation |

| Tree canopy coverage, density, and quantity | Urban trees |

| NDVI, green coverage (within 150–1000 m buffers around schools) | School greenery |

| Forest proximity; presence of urban forests; forest coverage and greenness | Urban forest |

| Park accessibility; number and size of urban parks | Urban parks |

| Green roof coverage, area, or scenario; green wall size | Green roofs and walls |

| Street view greenery; green view index; size, species, and condition of street trees | Green streets |

| Grassland coverage | Grassland |

| Garden coverage; green configuration | Community gardens |

| UGI Type | Climate Pathway | Health Benefits (↓ Reduced; ↑ Increased) | Contextual Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential greenery | Air pollution mitigation, heat reduction | ↓ Mortality, ↓ CVDs, ↑ respiratory health, ↑ metabolic health, ↓ obesity, ↓ cancer risk, ↑ birth outcomes, ↑ mental health and well-being | Age (children, older adults, women) and low-SES groups; vegetation diversity; UGI connectivity and clustering |

| Urban vegetation | Background air pollution reduction, UHI mitigation | ↓ Mortality, ↓ CVDs, ↑ respiratory health, ↓ obesity, ↑ life satisfaction | Urban density; low-SES areas; extreme air pollution; UGI clustering and connectivity |

| Urban trees | Heat reduction, air pollution removal | ↓ Mortality, ↓ CVDs, ↑ respiratory health, ↑ psychological restoration | Age (older adults) and heat-vulnerable groups; allergenic species; canopy continuity; crown volume |

| School greenery | Air pollution mitigation, heat reduction | ↓ CVDs, ↑ respiratory and metabolic health, ↓ obesity, ↑ cognition and visual health, ↑ well-being | Children in low-SES households; allergenic species |

| Urban forest | Air pollution removal, cooling | ↑ Respiratory health, ↓ CVDs, ↓ mortality, ↑ stress recovery | Distance to; canopy depth; stand density |

| Urban parks | Thermal comfort, air pollution mitigation | ↑ Happiness, ↑ stress recovery, partial respiratory and CVD benefits | Age (younger adults); extreme air pollution; semi-open urban layouts; availability of shading |

| Green roofs and walls | Indoor cooling, thermal comfort | ↓ Heat-related mortality, ↓ stress, ↑ positive emotions | Local climate; coverage density; integration with other UGI |

| Green streets | Heat reduction, pollution mitigation | ↓ CVD mortality, ↑ respiratory health, ↑ thermal comfort, ↑ emotional recovery | Age (women); allergenic species; tree line continuity; wind/solar orientation |

| Grassland | Air pollution mitigation, mild cooling | ↑ Physical health, ↑ sleep quality | Species diversity |

| Community gardens | Air pollution mitigation, heat reduction | ↑ Respiratory health, ↓ diabetes risk, ↑ mood and well-being | Extreme air pollution; other shading; availability of vertical greening |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, Y.; Turcu, C. Climate, Health, and Urban Green Infrastructure: The Evidence Base and Implications for Urban Policy and Spatial Planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121842

Jia Y, Turcu C. Climate, Health, and Urban Green Infrastructure: The Evidence Base and Implications for Urban Policy and Spatial Planning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121842

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Yirong, and Catalina Turcu. 2025. "Climate, Health, and Urban Green Infrastructure: The Evidence Base and Implications for Urban Policy and Spatial Planning" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121842

APA StyleJia, Y., & Turcu, C. (2025). Climate, Health, and Urban Green Infrastructure: The Evidence Base and Implications for Urban Policy and Spatial Planning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121842