Prevalence and Impact of Substance Use on Hospitalization and Post-Discharge Outcomes in Individuals with Congestive Heart Failure: Findings from a Safety-Net Hospital †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection and Variables

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographics

3.2. Prevalence of Substance Use

3.3. Patient Characteristics by Substance Use

3.4. Substance Use and Hospitalization Outcomes

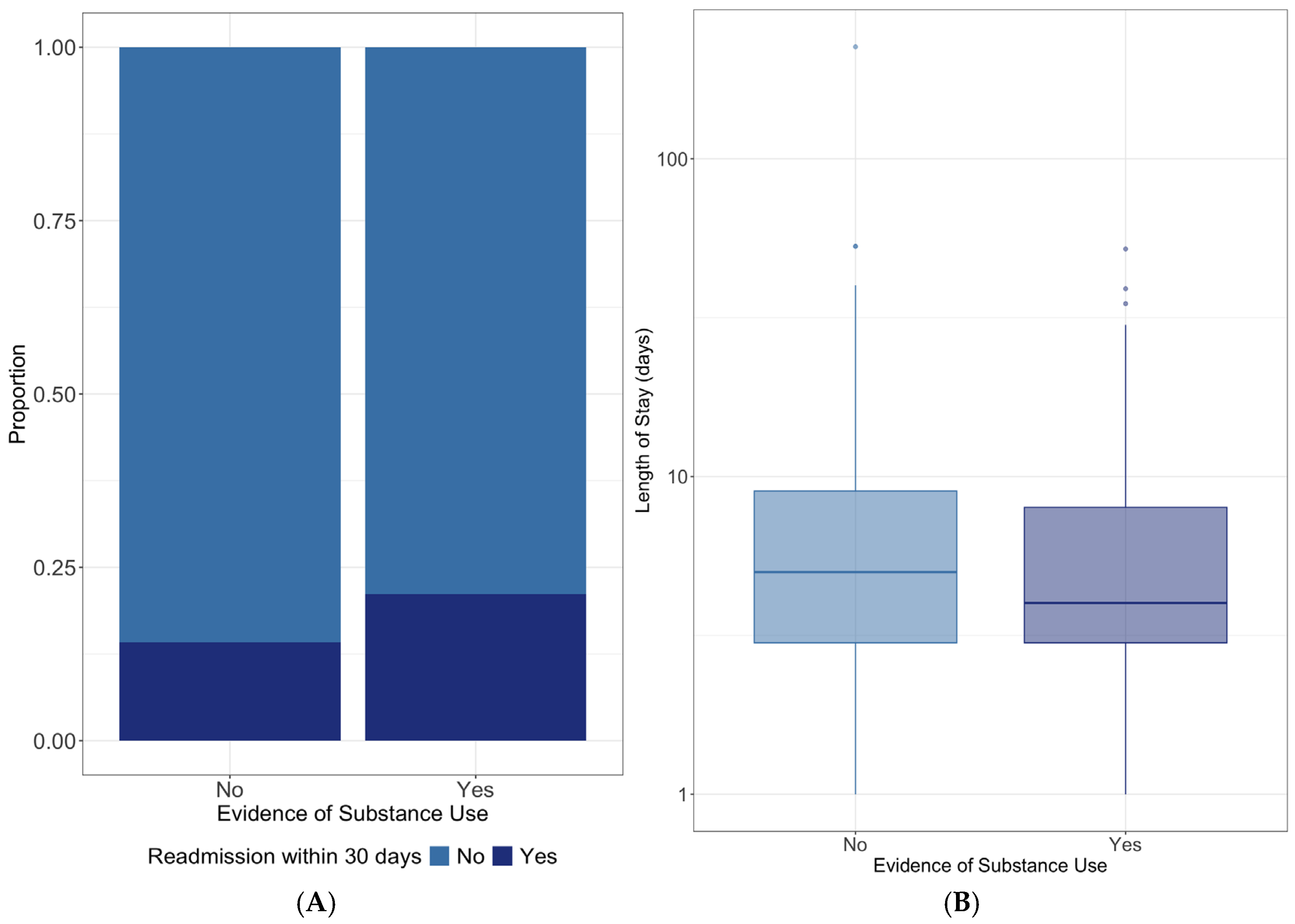

3.5. Follow-Up Appointments and Future Admissions

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Groenewegen, A.; Rutten, F.H.; Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, H.; Kronmal, R.; Bluemke, D.A.; Olson, J.; Shea, S.; Liu, K.; Burke, G.L.; Lima, J.A. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 2138–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaeian, B.; Fonarow, G.C. Epidemiology and aetiology of heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.L.; Tong, X.; King, R.J.; Loustalot, F.; Hong, Y.; Ritchey, M.D. National Burden of Heart Failure Events in the United States, 2006 to 2014. Circ. Heart Fail. 2018, 11, e004873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enard, K.R.; Coleman, A.M.; Yakubu, R.A.; Butcher, B.C.; Tao, D.; Hauptman, P.J. Influence of Social Determinants of Health on Heart Failure Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e026590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hawkins, N.M.; Jhund, P.S.; McMurray, J.J.; Capewell, S. Heart failure and socioeconomic status: Accumulating evidence of inequality. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2012, 14, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, Z.J.; McCoy, L.A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Yancy, C.W.; Miranda, M.L.; Peterson, E.D.; Califf, R.M.; Hernandez, A.F. Utility of socioeconomic status in predicting 30-day outcomes after heart failure hospitalization. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, S.S.; Masoudi, F.A.; Wang, Y.; Curtis, J.P.; Foody, J.M.; Havranek, E.P.; Krumholz, H.M. Socioeconomic status, treatment, and outcomes among elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure: Findings from the National Heart Failure Project. Am. Heart J. 2006, 152, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.A.; Krasnow, M.; Long, K.; Shirey, T.; Dickert, N.; Morris, A.A. Excess 30-Day Heart Failure Readmissions and Mortality in Black Patients Increases With Neighborhood Deprivation. Circ. Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e007947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McLellan, A.T. Substance Misuse and Substance use Disorders: Why do they Matter in Healthcare? Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2017, 128, 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health; HHS publication no PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M.F.; Creamer, M.R.; Parker, E.M. Substance Use Epidemiology as a Foundation for Prevention. Focus 2024, 22, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghuran, A.; van Der Wieken, L.R.; Nolan, J. Cardiovascular complications of recreational drugs. BMJ 2001, 323, 464–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, M.; Bhatia, H.; Ma, J.; Dickson, S.D.; Alshawabkeh, L.; Adler, E.; Maisel, A.; Criqui, M.H.; Greenberg, B.; Thomas, I.C. The Impact of Substance Abuse on Heart Failure Hospitalizations. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 207–213.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slim, A.M.; Thomas, H.; Parish, R.; Mansi, I. Comparison of outcomes of illicit drug users and nonusers hospitalized with heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, L.S.; Doering, L.V.; Dracup, K. Usefulness of a history of tobacco and alcohol use in predicting multiple heart failure readmissions among veterans. Am. J. Cardiol. 2000, 86, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasingham, R.; Moore, B.J.; Tabak, Y.P.; Drazner, M.H.; Clark, C.A.; Zhang, S.; Reed, W.G.; Swanson, T.S.; Ma, Y.; Halm, E.A. An automated model to identify heart failure patients at risk for 30-day readmission or death using electronic medical record data. Med. Care 2010, 48, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.; Allen, M.; Rocha, I. Community Health Needs Assessment 2019. Available online: https://hhinternet.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/2019/08/chna-2019.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment 2019–2021. Available online: https://www.nyp.org/pdf/community-service/NYPH-CHNA-2019-2021.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Grubb, A.F.; Greene, S.J.; Fudim, M.; Dewald, T.; Mentz, R.J. Drugs of Abuse and Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2021, 27, 1260–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, S.C.; Fonarow, G.C.; Ladapo, J.A.; Washington, D.L.; Hoggatt, K.J.; Ziaeian, B. National Rate of Tobacco and Substance Use Disorders Among Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 478–488.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, I.; Stein, J.A.; Nyamathi, A.; Bentler, P.M. Predictors of substance abuse treatment participation among homeless adults. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2014, 46, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Rucker, T.D. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financ. Rev. 2000, 21, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.T.; Latkin, C.A. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, personal network attributes, and use of heroin and cocaine. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32 (Suppl. 6), S203–S210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptiste-Roberts, K.; Hossain, M. Socioeconomic Disparities and Self-reported Substance Abuse-related Problems. Addict. Health 2018, 10, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.T.; Park, T. Acute and Chronic Effects of Cocaine on Cardiovascular Health. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garry, J.D.; Thakkar, A.B.; Durstenfeld, M.S.; Ma, Y.; Win, S.; Hsue, P.Y. Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure Using Cocaine. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 176, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total Study Sample (n = 500) | Evidence of Substance Use n = 189 (38%) | No Substance Use n = 311 (62%) | p-Value ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) * | 65 (13) | 60 (10) | 69 (14) | <0.001 |

| Males, n (%) | 279 (56%) | 125 (66%) | 154 (50%) | 0.0003 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) * | 31 (9) | 30 (9) | 32 (9) | 0.04 |

| Insurance Plan, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Medicare | 184 (37%) | 43 (23%) | 141 (45%) | |

| Medicaid | 222 (44%) | 116 (61%) | 106 (34%) | |

| Other | 61 (12%) | 20 (11%) | 41 (13%) | |

| Uninsured | 23 (5%) | 6 (3%) | 17 (5%) | |

| More than one | 9 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 5 (2%) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.046 | |||

| White/Other | 14 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 11 (4%) | |

| African American | 379 (76%) | 155 (82%) | 224 (72%) | |

| Hispanic | 58 (12%) | 14 (7%) | 44 (14%) | |

| Unknown | 49 (10%) | 17 (9%) | 32 (10%) | |

| Living Condition, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Permanent Residence | 434 (87%) | 151 (80%) | 283 (91%) | |

| Homeless | 33 (7%) | 27 (14%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Extended Care Facility | 15 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 10 (3%) | |

| Unable to Determine | 18 (4%) | 6 (3%) | 12 (4%) | |

| Income, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Employed | 55 (11%) | 15 (8%) | 40 (13%) | |

| Pension | 12 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (4%) | |

| Government Assistance | 253 (51%) | 112 (59%) | 141 (45%) | |

| Family Support | 35 (7%) | 10 (5%) | 25 (8%) | |

| None | 115 (23%) | 42 (22%) | 73 (23%) | |

| Unable to Determine | 30 (6%) | 10 (5%) | 20 (6%) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 452 (90%) | 172 (91%) | 280 (90%) | 0.8 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 231 (46%) | 74 (39%) | 157 (50%) | 0.02 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 231 (46%) | 84 (44%) | 147 (47%) | 0.6 |

| Coronary Artery Disease, n (%) | 154 (31%) | 60 (32%) | 94 (30%) | 0.8 |

| History of Atrial Fib/Flutter, n (%) | 112 (22%) | 31 (16%) | 81 (26%) | 0.01 |

| Sleep Apnea, n (%) | 71 (14%) | 22 (12%) | 49 (16%) | 0.2 |

| COPD/asthma, n (%) | 179 (36%) | 85 (45%) | 94 (30%) | 0.001 |

| History of Renal Disease, n (%) | 214 (43%) | 73 (39%) | 141 (45%) | 0.2 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 238 (48%) | 78 (41%) | 160 (51%) | 0.03 |

| Anemia, n (%) | 262 (52%) | 98 (52%) | 164 (53%) | 0.8 |

| CVA or TIA, n (%) | 95 (19%) | 30 (16%) | 65 (21%) | 0.2 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease, n (%) | 55 (11%) | 17 (9%) | 38 (12%) | 0.3 |

| Valvular Heart Disease, n (%) | 75 (15%) | 17 (9%) | 58 (19%) | 0.003 |

| CHF diagnosis prior to IH, n (%) | 321 (64%) | 127 (67%) | 194 (62%) | 0.3 |

| Current cigarette smoker, n (%) | 166 (33%) | 117 (62%) | 49 (16%) | <0.001 |

| Daily alcohol use, n (%) | 33 (7%) | 24 (13%) | 9 (3%) | <0.001 |

| Substance Used | Overall Substance Use Prevalence, n = 189 | All-Time Prevalence by UTOX n = 134 | All-Time Prevalence by Social History n = 124 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barbiturate, n (%) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Benzodiazepine, n (%) | 26 (14) | 26 (19) | 2 (2) |

| Cocaine, n (%) | 118 (62) | 79 (59) | 108 (87) |

| Methadone, n (%) | 24 (13) | 22 (16) | 5 (4) |

| Opiates, n (%) | 59 (31) | 43 (32) | 40 (32) |

| PCP, n (%) | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| THC, n (%) | 119 (63) | 37 (28) | 113 (91) |

| Amphetamines, n (%) | 6 (3) | 6 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Other, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Total Patients (n = 500) | No Substance Use n = 311 (62%) * | Evidence of Substance Use n = 189 (38%) * | p-Value ** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOS of index hospitalization | 5.0 [3.0, 8.0] | 5.0 [3.0, 9.0] | 4.0 [3.0, 8.0] | 0.04 |

| Attendance at any follow-up appointment at Harlem Cardiology Clinic | 238 (48%) | 160 (51%) | 78 (41%) | 0.03 |

| Readmitted within 30 days of index hospitalization | 84 (17%) | 44 (14%) | 40 (21%) | 0.048 |

| 30 day readmission related to CHF | 61 (12%) | 32 (10%) | 29 (15%) | 0.12 |

| Total number of hospital readmissions after index hospitalization | 1.0 [0.0, 3.0] | 1.0 [0.0, 2.0] | 2.0 [1.0, 4.0] | <0.0001 |

| Substance Used | Readmission Rate at 30 Day, n (%) | All Time Readmission Rate, Median [IQR] |

|---|---|---|

| Barbiturates, n = 3, n (%) | 1 (33%) | 10.0 [0.0, 16.0] |

| Benzodiazepines, n = 26, n (%) | 9 (35%) | 3.0 [0.0, 6.0] |

| Cocaine, n = 118, n (%) | 29 (25%) | 2.0 [0.5, 4.0] |

| Methadone, n = 24, n (%) | 10 (42%) | 3.5 [1.0, 5.5] |

| Opiates, n = 59, n (%) | 19 (32%) | 2.0 [1.0, 5.0] |

| PCP, n = 4, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 2.0 [0.5, 3.5] |

| THC, n = 119, n (%) | 18 (15%) | 1.0 [0.0, 4.0] |

| Amphetamines, n = 6, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 3.0 [0.0, 8.0] |

| Daily Alcohol, n = 33, n (%) | 5 (15%) | 1.0 [0.0, 3.0] |

| Current Smoker, n = 166, n (%) | 33 (20%) | 2.0 [0.0, 4.0] |

| Any Substance Use, n = 189, n (%) | 40 (21%) | 2.0 [1.0, 4.0] |

| No Overall Substance Use, n = 311, n (%) | 44 (14%) | 1.0 [0.0, 2.0] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majdalani, R.; AlShammari, A.; Thearle, M.; Magdits, M.; Shah, J.; Ionescu, N.; Kurian, D.; Raiszadeh, F. Prevalence and Impact of Substance Use on Hospitalization and Post-Discharge Outcomes in Individuals with Congestive Heart Failure: Findings from a Safety-Net Hospital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121832

Majdalani R, AlShammari A, Thearle M, Magdits M, Shah J, Ionescu N, Kurian D, Raiszadeh F. Prevalence and Impact of Substance Use on Hospitalization and Post-Discharge Outcomes in Individuals with Congestive Heart Failure: Findings from a Safety-Net Hospital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121832

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajdalani, Rosemarie, Asmaa AlShammari, Marie Thearle, Mariel Magdits, Jinal Shah, Natalia Ionescu, Damian Kurian, and Farbod Raiszadeh. 2025. "Prevalence and Impact of Substance Use on Hospitalization and Post-Discharge Outcomes in Individuals with Congestive Heart Failure: Findings from a Safety-Net Hospital" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121832

APA StyleMajdalani, R., AlShammari, A., Thearle, M., Magdits, M., Shah, J., Ionescu, N., Kurian, D., & Raiszadeh, F. (2025). Prevalence and Impact of Substance Use on Hospitalization and Post-Discharge Outcomes in Individuals with Congestive Heart Failure: Findings from a Safety-Net Hospital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121832