Behavioral and Sociodemographic Predictors of Diabetes Among Non-Hispanic Multiracial Adults in the United States: Using the 2023 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Design

2.2. Sample Description

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Health-Related Behaviors

3.3. Predictors of Diabetes

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roglic, G. WHO Global report on diabetes: A summary. Int. J. Noncommunicable Dis. 2016, 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Bannuru, R.R.; Beverly, E.A.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Cusi, K.; Darville, A.; Das, S.R.; et al. Introduction and Methodology: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S1–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arokiasamy, P.; Salvi, S.; Mani, S. Global Burden of Diabetes Mellitus. In Handbook of Global Health; Haring, R., Kickbusch, I., Ganten, D., Moeti, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Puchulu, F.M. Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. In Dermatology and Diabetes; Cohen Sabban, E.N., Puchulu, F.M., Cusi, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W. Global, regional, and national burdens of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus in adolescents from 1990 to 2021, with forecasts to 2030: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onufrak, S.; Saelee, R.; Zaganjor, I.; Miyamoto, Y.; Koyama, A.K.; Xu, F.; Pavkov, M.E.; Bullard, K.M.; Imperatore, G. Prevalence of Self-Reported Diagnosed Diabetes Among Adults, by County Metropolitan Status and Region, United States, 2019–2022. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2024, 21, E81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Danpanichkul, P.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Ahmed, A. Healthcare and prescription medication affordability in adults with diabetes in the United States, 2020–2023. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 226, 112340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, S.M.; Walker, R.J.; Garacci, E.; Dawson, A.Z.; Campbell, J.A.; Egede, L.E. Explanatory role of sociodemographic, clinical, behavioral, and social factors on cognitive decline in older adults with diabetes. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Fiorillo, S. National Diabetes Month: The History and Impact. Available online: https://www.endocrinologyadvisor.com/features/national-diabetes-month/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- McMaughan, D.J.; Oloruntoba, O.; Smith, M.L. Socioeconomic Status and Access to Healthcare: Interrelated Drivers for Healthy Aging. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.E.; Wijeweera, C.; Wijeweera, A. Lifestyle and socioeconomic determinants of diabetes: Evidence from country-level data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, A.; Zhang, K.; Luo, B. Diabetes risk among US adults with different socioeconomic status and behavioral lifestyles: Evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1197947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, A.; Casagrande, S.; Geiss, L.; Cowie, C.C. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 2015, 314, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.J.; Imperatore, G.; Geiss, L.S.; Saydah, S.H.; Albright, A.L.; Ali, M.K.; Gregg, E.W. Trends and Disparities in Cardiovascular Mortality Among U.S. Adults With and Without Self-Reported Diabetes, 1988–2015. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2306–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Adler, N.E.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Chin, M.H.; Gary-Webb, T.L.; Navas-Acien, A.; Thornton, P.L.; Haire-Joshu, D. Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes: A Scientific Review. Diabetes Care 2020, 44, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Gujral, U.P.; Quarells, R.C.; Rhodes, E.C.; Shah, M.K.; Obi, J.; Lee, W.H.; Shamambo, L.; Weber, M.B.; Narayan, K.M.V. Disparities in diabetes prevalence and management by race and ethnicity in the USA: Defining a path forward. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, P.; Barker, L.E.; Chowdhury, F.M.; Zhang, X. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to prevent and control diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1872–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, C.W.; Suh, Y.J.; Hong, S.; Ahn, S.H.; Seo, D.H.; Nam, M.S.; Chon, S.; Woo, J.T.; et al. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Health Behaviors, Metabolic Control, and Chronic Complications in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 2018, 42, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voight, B.F.; Scott, L.J.; Steinthorsdottir, V.; Morris, A.P.; Dina, C.; Welch, R.P.; Zeggini, E.; Huth, C.; Aulchenko, Y.S.; Thorleifsson, G.; et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Taliun, D.; Thurner, M.; Robertson, N.R.; Torres, J.M.; Rayner, N.W.; Payne, A.J.; Steinthorsdottir, V.; Scott, R.A.; Grarup, N.; et al. Fine-mapping type 2 diabetes loci to single-variant resolution using high-density imputation and islet-specific epigenome maps. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaff, J.; Wang, X.; Cubbage, J.; Bandara, S.; Wilcox, H.C. Mental health and Multiracial/ethnic adults in the United States: A mixed methods participatory action investigation. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1286137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellou, V.; Belbasis, L.; Tzoulaki, I.; Evangelou, E. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus: An exposure-wide umbrella review of meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Rios, L.K.; Stage, V.C.; Leak, T.M.; Taylor, C.A.; Reicks, M. Collecting, Using, and Reporting Race and Ethnicity Infor-mation: Implications for Research in Nutrition Education, Practice, and Policy to Promote Health Equity. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.; Marks, R.; Ramirez, R.; Ríos-Vargas, M. 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Izadi, N.; Shafiee, A.; Niknam, M.; Yari-Boroujeni, R.; Azizi, F.; Amiri, P. Socio-behavioral determinants of health-related quality of life among patients with type 2 diabetes: Comparison between 2015 and 2018. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2024, 24, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacker, K.; Thomas, C.W.; Zhao, G.; Claxton, J.S.; Eke, P.; Town, M. Social Determinants of Health and Health-Related Social Needs Among Adults With Chronic Diseases in the United States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2022. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2024, 21, E94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Overview: BRFSS 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2023/pdf/Overview_2023-508.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Pierannunzi, C.; Hu, S.S.; Balluz, L. A systematic review of publications assessing reliability and validity of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2004–2011. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Holt, J.B.; Lu, H.; Wheaton, A.G.; Ford, E.S.; Greenlund, K.J.; Croft, J.B. Multilevel regression and poststratification for small-area estimation of population health outcomes: A case study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence using the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 179, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bursac, Z.; Gauss, C.H.; Williams, D.K.; Hosmer, D.W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 2008, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.Z.I.; Turin, T.C. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Strings, S.; Wells, C.; Bell, C.; Tomiyama, A.J. The association of body mass index and odds of type 2 diabetes mellitus varies by race/ethnicity. Public Health 2023, 215, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Kim, J.H.; Sumerlin, T.S.; Feng, Q.; Yu, J. Metabolic health and adiposity transitions and risks of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavaddat, N.; Valderas, J.M.; van der Linde, R.; Khaw, K.T.; Kinmonth, A.L. Association of self-rated health with multimorbidity, chronic disease and psychosocial factors in a large middle-aged and older cohort from general practice: A cross-sectional study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeh, K.; Adaji, S. Can self-rated health be useful to primary care physicians as a diagnostic indicator of metabolic dysregulations amongst patients with type 2 diabetes? A population-based study. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.A.; Solis-Trapala, I.; Dahlstrom, U.; Mamas, M.; Jaarsma, T.; Kadam, U.T.; Stromberg, A. Comorbidity health pathways in heart failure patients: A sequences-of-regressions analysis using cross-sectional data from 10,575 patients in the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.B.; Jensen, P.; Gannik, D.; Reventlow, S.; Hollnagel, H.; Olivarius Nde, F. Change in self-rated general health is associated with perceived illness burden: A 1-year follow up of patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małkowska, P. Positive Effects of Physical Activity on Insulin Signaling. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 5467–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Norat, T.; Leitzmann, M.; Tonstad, S.; Vatten, L.J. Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 30, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahiddoust, F.; Monazzami, A.A. Exercise-induced changes in insulin sensitivity, atherogenic index of plasma, and CTRP1/CTRP3 levels: The role of combined and high-intensity interval training in overweight and obese women. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 17, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouk, K.; Triki, R.; Dergaa, I.; Ceylan, H.; Bougrine, H.; Raul-Ioan, M.; Ben Abderrahman, A. Effects of combined diet and physical activity on glycemic control and body composition in male recreational athletes with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1525559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaley, J.A.; Colberg, S.R.; Corcoran, M.H.; Malin, S.K.; Rodriguez, N.R.; Crespo, C.J.; Kirwan, J.P.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise/Physical Activity in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Consensus Statement from the American College of Sports Medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky, S.; Akturk, H.K. Alcohol Consumption, Diabetes Risk, and Cardiovascular Disease Within Diabetes. Curr. Diab Rep. 2017, 17, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, J.P.; Polsky, S.; Howard, A.A.; Perreault, L.; Bray, G.A.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Brown-Friday, J.; Whittington, T.; Foo, S.; Ma, Y.; et al. Alcohol consumption and diabetes risk in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Heianza, Y.; Qi, L. Moderate alcohol drinking with meals is related to lower incidence of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukamal, K.J.; Beulens, J.W.J. Limited alcohol consumption and lower risk of diabetes: Can we believe our own eyes? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 1460–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hur, J.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Song, M.; Liang, L.; Mukamal, K.J.; Rimm, E.B.; Giovannucci, E.L. Alcohol Intake, Drinking Pattern, and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Three Prospective Cohorts of U.S. Women and Men. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maskarinec, G.; Kristal, B.S.; Wilkens, L.R.; Quintal, G.; Bogumil, D.; Setiawan, V.W.; Le Marchand, L. Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes in the Multiethnic Cohort. Can. J. Diabetes 2023, 47, 627–635.e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, N.I.; Tehranifar, P.; Laferrère, B.; Albrecht, S.S. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Glycemic Control Among Insured US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2336307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, S.; Bradley, A.; Pitts, L.; Waletzko, S.; Robinson-Lane, S.G.; Fairchild, T.; Terbizan, D.J.; McGrath, R. Health Insurance Is Associated with Decreased Odds for Undiagnosed Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes in American Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Angier, H.; Springer, R.; Valenzuela, S.; Hoopes, M.; O’Malley, J.; Suchocki, A.; Heintzman, J.; DeVoe, J.; Huguet, N. The Affordable Care Act: Effects of Insurance on Diabetes Biomarkers. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2074–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Wang, D.; Coresh, J.; Selvin, E. Undiagnosed Diabetes in U.S. Adults: Prevalence and Trends. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1994–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, M.L.; Mukamal, K.J.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Ix, J.H.; Carnethon, M.R.; Newman, A.B.; de Boer, I.H.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; Mozaffarian, D.; Siscovick, D.S. Association between adiposity in midlife and older age and risk of diabetes in older adults. JAMA 2010, 303, 2504–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.; Saeedi, P.; Kaundal, A.; Karuranga, S.; Malanda, B.; Williams, R. Diabetes and global ageing among 65-99-year-old adults: Findings from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 162, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, M.; Hu, R.; Chen, G.; Su, Q.; Mu, Y.; et al. Age-related disparities in diabetes risk attributable to modifiable risk factor profiles in Chinese adults: A nationwide, population-based, cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e618–e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Le, M.H.; Yeo, Y.H.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Likhitsup, A.; Kim, D.; Chen, V.L. Diabetes prevalence and management patterns in US adults, 2001–2023. Acta Diabetol. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Sheng, H.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Q. Prevalence of diabetes in the USA from the perspective of demographic characteristics, physical indicators and living habits based on NHANES 2009–2018. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1088882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Bancks, M.P.; Carnethon, M.R.; Greenland, P.; Feng, Y.Q.; Wang, H.; Zhong, V.W. Trends in Prevalence of Diabetes and Control of Risk Factors in Diabetes Among US Adults, 1999–2018. JAMA 2021, 326, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, R.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, B.; Yin, K.; Cao, J.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Association Between Visceral Obesity Index and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 2692–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ji, J.; Liu, Y.J.; Deng, X.; He, Q.Q. Passive smoking and risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Graniel, I.; Kose, J.; Duquenne, P.; Babio, N.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Touvier, M.; Fezeu, L.K.; Andreeva, V.A. Alcohol, Smoking, and Their Synergy as Risk Factors for Incident Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2025, 69, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Liu, J.; Ning, G. Active smoking and risk of metabolic syndrome: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 18–64 years | 4992 | 77.65 |

| ≥65 years | 1437 | 22.35 |

| Sex of participants | ||

| Male | 3279 | 51.00 |

| Female | 3150 | 49.00 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Did not graduate high school | 284 | 4.42 |

| High school diploma | 1515 | 23.57 |

| Some college/technical school | 2026 | 31.51 |

| College graduate | 2604 | 40.50 |

| Annual household income | ||

| <$15,000 | 393 | 6.11 |

| $15,000 to <$25,000 | 610 | 9.49 |

| $25,000 to <$35,000 | 715 | 11.12 |

| $35,000 to <$50,000 | 873 | 13.58 |

| $50,000 to <$100,000 | 1987 | 30.91 |

| $100,000to <$200,000 | 1367 | 21.26 |

| ≥$200,000 | 484 | 7.53 |

| Health insurance status | ||

| No | 339 | 5.27 |

| Yes | 6090 | 94.73 |

| Residence Urbanicity | ||

| Urban | 5688 | 88.47 |

| Rural | 741 | 11.53 |

| Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

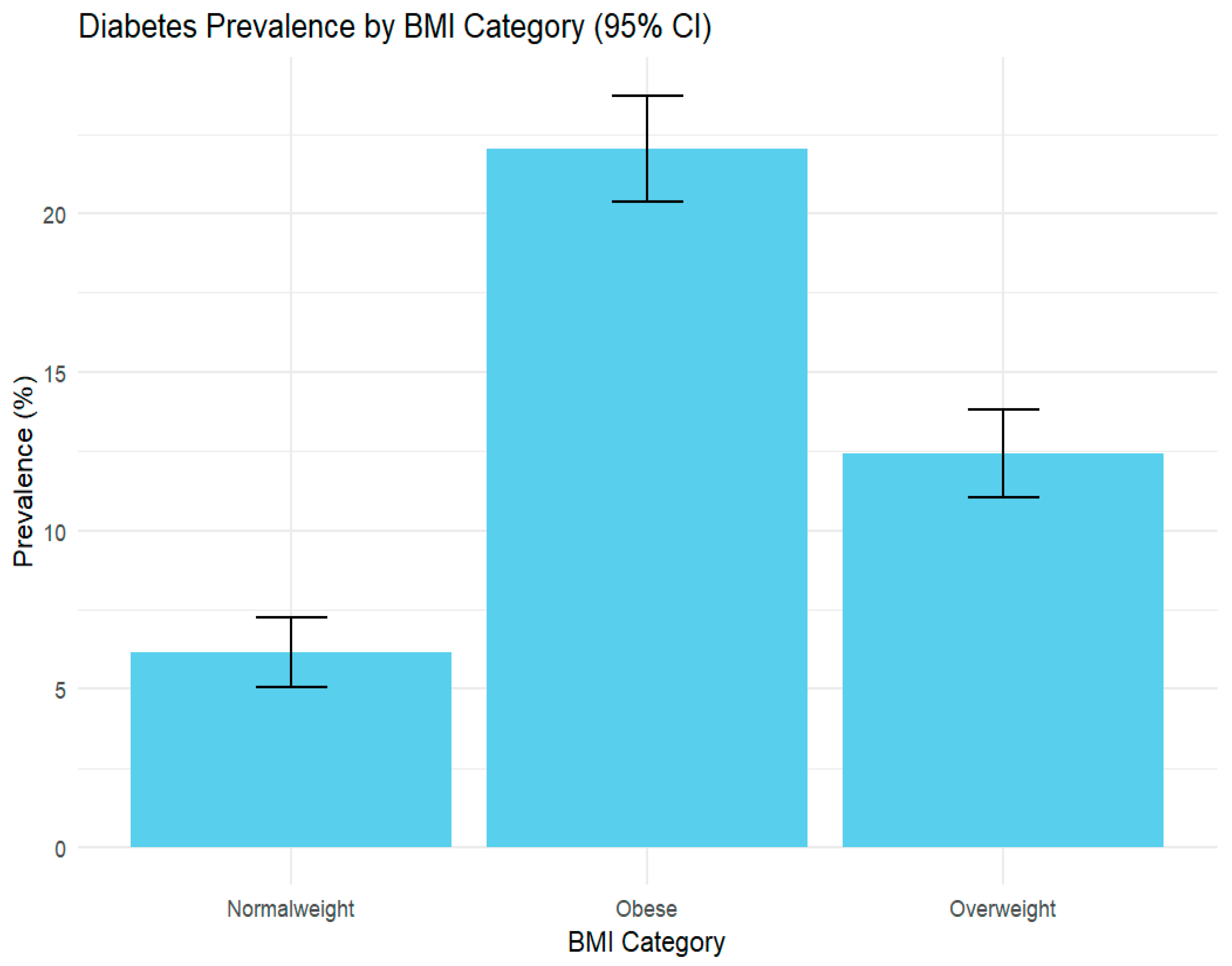

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||

| Normal weight | 1901 | 29.57 |

| Overweight | 2188 | 34.03 |

| Obese | 2340 | 36.40 |

| Physical activity in past 30 days | ||

| Yes | 5035 | 78.32 |

| No | 1394 | 21.68 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current smoker | 753 | 11.71 |

| Former smoker | 1928 | 30.00 |

| Never smoked | 3748 | 58.29 |

| Alcohol consumption (past 30 days) | ||

| Yes | 3460 | 53.82 |

| No | 2969 | 46.18 |

| General health status | ||

| Good or better | 5053 | 78.60 |

| Fair or poor | 1376 | 21.40 |

| History of depressive disorder | ||

| Yes | 1763 | 27.42 |

| No | 4666 | 72.58 |

| Characteristic | AOR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

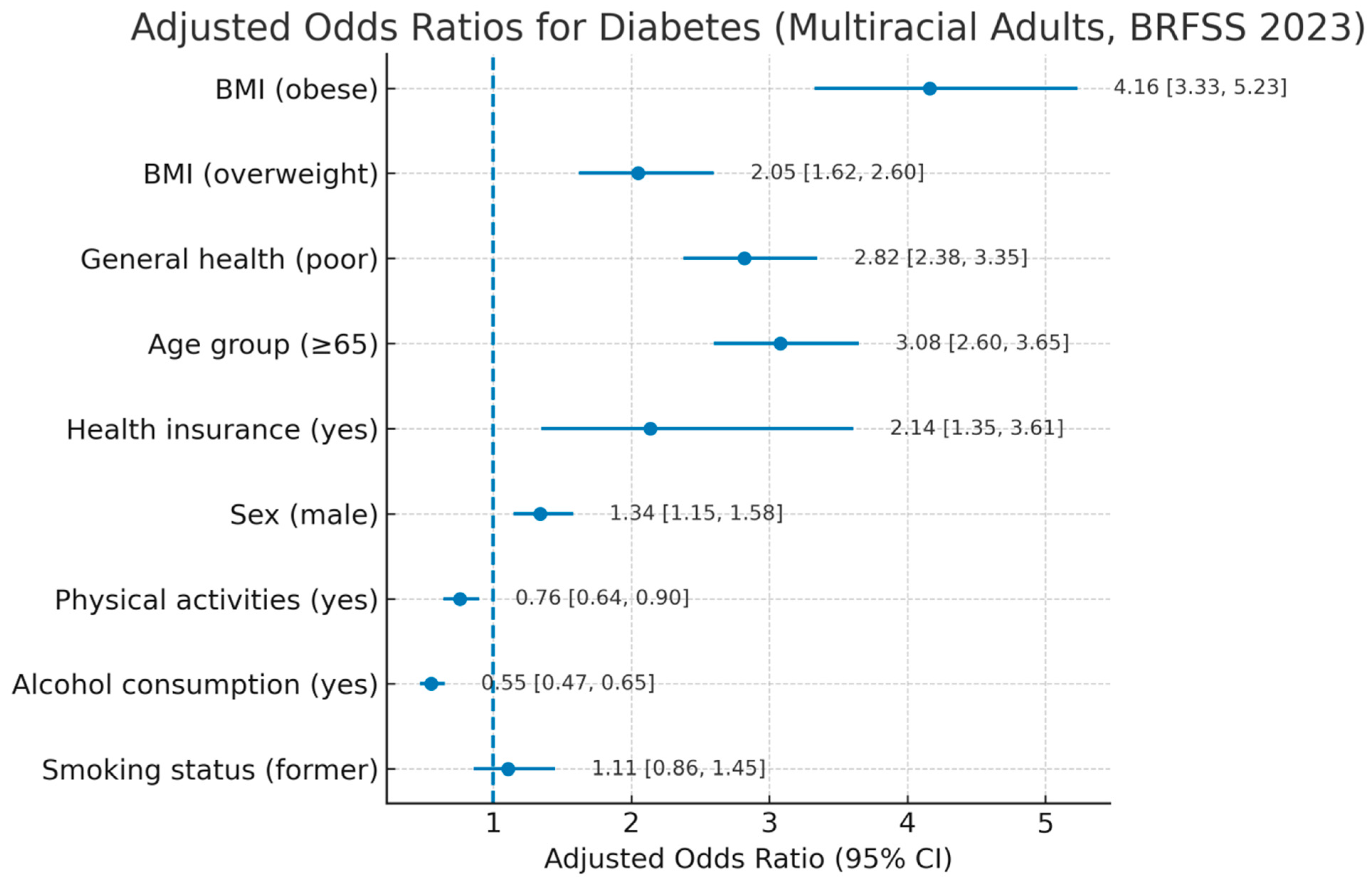

| Body mass index | |||

| Normal weight | |||

| Overweight | 2.05 | 1.62, 2.60 | <0.001 |

| Obese | 4.16 | 3.33, 5.23 | <0.001 |

| General health | |||

| Good or better | |||

| Fair or poor | 2.82 | 2.38, 3.35 | <0.001 |

| Age categories | |||

| Age 18 to 64 | |||

| Age 65 or older | 3.08 | 2.60, 3.65 | <0.001 |

| Health insurance | |||

| No | |||

| Yes | 2.14 | 1.35, 3.61 | 0.002 |

| Physical activity in past 30 days | |||

| No | |||

| Yes | 0.76 | 0.64, 0.90 | 0.002 |

| Sex of respondent | |||

| Female | |||

| Male | 1.34 | 1.15, 1.58 | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current smoker | |||

| Former smoker | 1.11 | 0.86, 1.45 | 0.4 |

| Never smoked | 1.0 | 0.77, 1.29 | >0.9 |

| Alcohol consumption (past 30 days) | |||

| No | |||

| Yes | 0.55 | 0.47, 0.65 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turuse, E.; Koshy-Chenthittayil, S.; Stone, A.E.L.; Gelaw, E.; Coughenour, C. Behavioral and Sociodemographic Predictors of Diabetes Among Non-Hispanic Multiracial Adults in the United States: Using the 2023 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121815

Turuse E, Koshy-Chenthittayil S, Stone AEL, Gelaw E, Coughenour C. Behavioral and Sociodemographic Predictors of Diabetes Among Non-Hispanic Multiracial Adults in the United States: Using the 2023 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121815

Chicago/Turabian StyleTuruse, Ermias, Sherli Koshy-Chenthittayil, Amy E. L. Stone, Edom Gelaw, and Courtney Coughenour. 2025. "Behavioral and Sociodemographic Predictors of Diabetes Among Non-Hispanic Multiracial Adults in the United States: Using the 2023 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121815

APA StyleTuruse, E., Koshy-Chenthittayil, S., Stone, A. E. L., Gelaw, E., & Coughenour, C. (2025). Behavioral and Sociodemographic Predictors of Diabetes Among Non-Hispanic Multiracial Adults in the United States: Using the 2023 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121815