Adaptation and Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS-BR) in the Context of Primary Health Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The MAKS

2.2. Translation

2.3. Content and Face Validation

2.4. Participants

2.5. Instruments

2.6. Data Collection Procedures

2.7. Data Analyses Procedures

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| MAKS | Mental Health Knowledge Schedule |

References

- Thornicroft, G.; Brohan, E.; Kassam, A.; Lewis-Holmes, E. Reducing stigma and discrimination: Candidate interventions. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2008, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornicroft, G.; Sunkel, C.; Aliev, A.A.; Baker, S.; Brohan, E.; El Chammay, R.; Davies, K.; Demissie, M.; Duncan, J.; Fekadu, W.; et al. The Lancet Commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. Lancet 2022, 400, 1438–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esponda, G.M.; Hartman, S.; Qureshi, O.; Sadler, E.; Cohen, A.; Kakuma, R. Barriers and facilitators of mental health programmes in primary care in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, T.M.D.; Torrenté, M.D. Saúde Mental no Brasil: Desafios para a construção de políticas de atenção e de monitoramento de seus determinantes. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude 2023, 32, e2023098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwuma, O.V.; Ezeani, E.I.; Fatoye, E.O.; Benjamin, J.; Okobi, O.E.; Nwume, C.G.; Egberuare, E.N. A systematic review of the effect of stigmatization on psychiatric illness outcomes. Cureus 2024, 16, e62642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, B.; Dovidio, J.F.; Link, B.G.; Calabrese, S.K. Stigma and its implication for health: Introduction and overview. In The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination and Health; Major, B., Dovidio, J.F., Link, B.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, C.; Noblett, J.; Parke, H.; Clement, S.; Caffrey, A.; Gale-Grant, O.; Schulze, B.; Druss, B.; Thornicroft, G. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistorte, A.O.R.; Ribeiro, W.S.; Jaen, D.; Jorge, M.R.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Mari, J.D.J. Stigmatizing attitudes of primary care professionals towards people with mental disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2018, 53, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Wang, C.; Cai, J.; Mu, Y.F.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zhang, T.M.; Zhao, X.Y.; Li, M.; Luo, W.; et al. Mental illness-related stigma and its associated factors among primary health care professionals in rural China. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1519527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xia, J.; Chen, W.; Ye, J.; Xie, K.; Zhang, Z.; Binti Mohamad, S.M.; Shuid, A.N. Exploring the interplay of mental health knowledge, stigma, and social distance among clinical nurses: A study in Liaoning, China. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1478690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Kallakuri, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Wahid, S.S.; Kohrt, B.A.; Thornicroft, G.; Maulik, P.K. Mental health related stigma, service provision and utilization in Northern India: Situational analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2023, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigozi-Male, N.G.; Heunis, J.C.; Engelbrecht, M.C. Primary health care nurses’ mental health knowledge and attitudes towards patients and mental health care in a South African metropolitan municipality. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffel, T.; Chen, S.P. Stigma in healthcare? Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural responses of healthcare professionals and students toward individuals with mental illnesses. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalky, H.F.; Abu-Hassan, H.H.; Dalky, A.F.; Al-Delaimy, W. Assessment of mental health stigma components of mental health knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among Jordanian healthcare providers. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 56, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohrt, B.A.; Jordans, M.J.; Turner, E.L.; Rai, S.; Gurung, D.; Dhakal, M.; Bhardwaj, A.; Lamichhane, J.; Singla, D.R.; Lund, C.; et al. Collaboration with people with lived experience of mental illness to reduce stigma and improve primary care services: A pilot cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2131475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, E.; Kohrt, B.A.; Koschorke, M.; Milenova, M.; Thronicroft, G. Reducing mental health-related stigma in primary health care settings in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 29, e3. [Google Scholar]

- Organização Mundial da Saúde. Plano de Ação em Saúde Mental 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Organização Mundial da Saúde. Atlas de Saúde Mental 2017; WHO Library Cataloguing: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft, G. Stigma and discrimination limit access to mental health care. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2008, 17, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Little, K.; Meltzer, H.; Rose, D.; Rhydderch, D.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Development and psychometric properties of the mental health knowledge schedule. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Public knowledge, attitudes and behaviour regarding people with mental illness in England 2009–2012. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, s51–s57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Corker, E.; Williams, P.; Henderson, C.; Thornicroft, G. Effect of the Time to Change anti-stigma campaign on trends in mental-illness-related public stigma among the English population in 2003–13: An analysis of survey data. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amor, M.; Zgueb, Y.; Bouguira, E.; Metsahel, A.; Aissa, A.; Thonicroft, G.; Ouali, U. Arabic validation of the “Mental Health Knowledge Schedule” and the “Reported and Intended Behavior Scale”. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1241611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, B.; Farhoudi, F.; Abedini, E. Psychometric validation of the Persian version of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 37, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingani, L.; Sampogna, G.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Gozzi, B.; Giallonardo, V.; Luciano, M.; Galeazzi, G.M.; Fiorillo, A. How to measure knowledge about mental disorders? Validation of the Italian version of the MAKS. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C.; Golay, P.; Favrod, J.; Bonsack, C. French translation and validation of three scales evaluating stigma in mental health. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pheh, K.S.; Ong, A. W-H.; Sow Kim, L.; Tan, C.-S.; Kok, J.K. The Malay version of the mental health knowledge schedule: A preliminary study. Malays. J. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, G.M.; Donovan, C.L.; March, S.; Laurenson, S.D. Logging into therapy: Parent attitudes and intentions to use computer-based therapies for youth mental health. Internet Interv. 2015, 2, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dimoff, J.K.; Kelloway, E.K.; Burnstein, M.D. Mental health awareness training (MHAT): The development and evaluation of an intervention for workplace leaders. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2016, 23, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideras, S.; McKenzie, G.; Noone, J.; Dieckmann, N.; Allen, T.L. Impact of a simulation on nursing students’ attitudes toward Schizophrenia. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2015, 11, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.J.; Rathod, S.D.; Hanlon, C.; Breuer, E.; Chisholm, D.; Fekadu, A.; Jordans, M.; Kigozi, F.; Petersen, I.; Shidhaye, R.; et al. Evaluation of district mental healthcare plans: The PRIME consortium methodology. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208 (Suppl. 56), s63–s70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Thornicroft, G.; Huang, Y. Levels of stigma among community mental health staff in Guangzhou, China. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, L.; Stjernswärd, S.; Svensson, B. Changes in attitudes, intended behaviour, and mental health literacy in the Swedish population 2009–2014: An evaluation of a national antistigma programme. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016, 134, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirne, M.; Mohungoo, N.; Buckley, S. Mental health knowledge and attitudes in a transition year student group: A pilot survey. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2013, 30, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Portney, L.; Watkins, M. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice; Prentice Hall Health: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Foygel, R.; Drton, M. Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2010, 23, 604–612. [Google Scholar]

- Robinaugh, D.J.; Millner, A.J.; McNally, R.J. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.J.; Ma, R.; McNally, R.J. Bridge centrality: A network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2019, 54, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.J.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.S.; Hall, B.J.; Su, T.T.; Prawira, B.; Breth-Petersen, M.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, T.-M. Stigma of mental illness and cultural factors in Pacific Rim region: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflakseir, A.; Esini, M.R.; Goodarzi, M.; Molazadeh, J. Individuals with mental illness and stigma reduction: A cross-sectional study in a group of college students. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2019, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, A.L.; Frasso, R.; Ran, M.S.; Zhang, T.M.; Kong, D.; Wong, Y.L.I. Mental health-related stigma and attitudes toward patient care among providers of mental health services in a rural Chinese county. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Fernández, A.B.; Lombardero Posada, X.; Aguiar Fernández, F.X.; Murcia Álvarez, E.; González Fernández, A. Professional preference for mental illness: The role of contact, empathy, and stigma in Spanish social work undergraduates. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 1492–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.S.; Peng, M.M.; Yau, Y.Y.; Zhang, T.M.; Li, X.H.; Wong, I.Y.L.; Ng, S.; Thornicroft, G.; Chan, C.L.-W.; Lu, L. Knowledge, contact and stigma of mental illness: Comparing three stakeholder groups in Hong Kong. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, P.; Chalise, A.; Khatri, D.; Poudel, S.; Paudel, S. Mental health literacy among basic healthcare providers and community health volunteers of Lalitpur Metropolitan City, Nepal. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangu, E.; Mansouri, F.; Sands, N.; Ndetei, D.; Muriithi, P.; Wynter, K.; Rawson, H. Assessing mental health literacy of primary health care workers in Kenya: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Original Instrument | Brazilian Portuguese Translated and Adaptaded |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Most people with mental health problems want to have paid employment | A maioria das pessoas com problemas de saúde mental quer ter um trabalho remunerado. |

| 2 | If a friend had a mental health problem, I know what advice to give them to get professional help. | Se um amigo tiver um problema de saúde mental, eu sei como aconselhá-lo para obter ajuda profissional. |

| 3 | Medication can be an effective treatment for people with mental health problems. | A medicação pode ser um tratamento eficaz para pessoas com problemas de saúde mental. |

| 4 | Psychotherapy (e.g. talking therapy or counselling) can be an effective treatment for people with mental health problems. | A psicoterapia pode ser um tratamento eficaz para pessoas com problemas de saúde mental. |

| 5 | People with severe mental health problems can fully recover. | Pessoas com sérios problemas de saúde mental podem se recuperar totalmente. |

| 6 | Most people with mental health problems go to a healthcare professional to get help. | A maioria das pessoas com problemas de saúde mental recorre a um profissional de saúde para obter ajuda. |

| 7 | Depression is a type of mental illness | Depressão é um tipo de doença mental |

| 8 | Stress is a type of mental illness | Estresse é um tipo de doença mental |

| 9 | Schizophrenia is a type of mental illness | Esquizofrenia é um tipo de doença mental |

| 10 | Bipolar disorder (manic-depression) is a type of mental illness | Transtorno bipolar é um tipo de doença mental |

| 11 | Drug addiction is a type of mental illness | Dependência de drogas é um tipo de doença mental |

| 12 | Grief is a type of mental illness | Luto é um tipo de doença mental |

| Variable | Characteristics | % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 19–29 | 16.6 (48) |

| 30–39 | 37.7 (109) | |

| 40–49 | 27.7 (80) | |

| 50–59 | 15.9 (46) | |

| >60 | 1.7 (5) | |

| Sex | Female | 90.3 (261) |

| Male | 9.7 (28) | |

| Race/color | White | 74.7 (216) |

| Brown | 14.5 (42) | |

| Asian | 1.0 (3) | |

| Black | 8.0 (23) | |

| Indigenous | 0.3 (1) | |

| Other | 1.4 (4) | |

| Marital status | Single | 31.5 (91) |

| Civil partnership | 22.8 (66) | |

| Married | 34.6 (100) | |

| Separated/divorced | 10 (29) | |

| Widower/widow | 0.7 (2) | |

| Education | Primary education to incomplete secondary education | 2.4 (7) |

| Complete secondary education | 18.3 (53) | |

| Incomplete higher education | 9.3 (27) | |

| Comple higher education | 15.9 (46) | |

| Postgraduate studies | 54.0 (156) | |

| Occupation | Nurse | 31.5 (91) |

| Community health worker | 22.5 (65) | |

| Physician | 12.5 (36) | |

| Nursing assistant or technician | 9.3 (27) | |

| Dentist | 6.9 (20) | |

| Psychologist | 4.5 (13) | |

| Manager | 4.2(12) | |

| Other | 8.3 (24) | |

| Working time | Less than 1 year | 12.8 (37) |

| 1 to 3 years | 15.9 (46) | |

| 3 to 5 years | 9.3 (27) | |

| 5 to 10 years | 30.8 (89) | |

| 10 to15 years | 12.5 (36) | |

| 15 to 20 years | 9.7 (28) | |

| More than 20 years | 8 (23) | |

| Mental health training | Sim | 22.8 (66) |

| Não | 77.2 (233) | |

| Frequency of contact with people with mental disorders | Daily | 24.7 (71) |

| Weekly | 27.9 (80) | |

| Monthly | 17.4 (50) | |

| Rarely | 20.9 (60) | |

| Never | 1.7 (5) |

| Item | Agree Strongly | Agree Slightly | Neither Agree nor Disagree/Don’t Know | Disagree Slightly | Disagree Strongly | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| 1. Most people with mental health problems want to have paid employment. | 30.8 | 89 | 45.3 | 131 | 11.8 | 34 | 9.7 | 28 | 2.1 | 6 |

| 2. If a friend had a mental health problem, I know what advice to give them to get professional help. | 58.5 | 169 | 35.3 | 102 | 4.5 | 13 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.7 | 2 |

| 3. Medication can be an effective treatment for people with mental health problems. | 37.0 | 107 | 56.4 | 163 | 2.4 | 7 | 3.1 | 9 | 1.0 | 3 |

| 4. Psychotherapy can be an effective treatment for people with mental health problems | 67.5 | 195 | 28.4 | 82 | 2.8 | 8 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.3 | 1 |

| 5. People with severe mental health problems can fully recover. | 17.0 | 49 | 53.3 | 153 | 14.5 | 42 | 11.4 | 33 | 3.8 | 11 |

| 6. Most people with mental health problems go to a healthcare professional to get help. | 12.1 | 35 | 35.6 | 103 | 7.6 | 22 | 33.9 | 98 | 10.7 | 31 |

| 7. Depression is a type of mental illness. | 78.5 | 227 | 15.6 | 45 | 3.5 | 10 | 0.3 | 1 | 2.1 | 6 |

| 8. Stress is a type of mental illness. | 8.0 | 23 | 6.6 | 19 | 8.7 | 25 | 36.0 | 104 | 40.8 | 118 |

| 9. Schizophrenia is a type of mental illness. | 93.8 | 271 | 4.2 | 12 | 1.4 | 4 | 0.7 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 10. Bipolar disorder (manic-depression) is a type of mental illness. | 89.6 | 259 | 8.7 | 25 | 1.4 | 4 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. Drug addiction is a type of mental illness. | 60.2 | 174 | 26.0 | 75 | 4.2 | 12 | 6.6 | 19 | 3.1 | 9 |

| 12. Grief is a type of mental illness. | 21.1 | 61 | 28.4 | 82 | 8.0 | 23 | 12.1 | 35 | 30.4 | 88 |

| MAKS-12 | F.L. | S.E. | 95% I.C. | Thresholds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Item | L. | H. | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t5 | ||

| MHK | 1 | 0.324 * | 0.204 | 0.445 | −0.502 | 0.722 | 0.970 | 1.482 | 1.660 | |

| MHK | 2 | 0.645 * | 0.566 | 0.524 | 0.765 | 0.214 | 1.536 | 1.817 | 1.973 | 2.113 |

| MHK | 3 | 0.650 * | 0.430 | 0.555 | 0.745 | −0.331 | 1.508 | 1.627 | 2.038 | 2.312 |

| MHK | 4 | 0.628 * | 0.606 | 0.513 | 0.743 | 0.453 | 1.733 | 1.817 | 1.973 | 2.038 |

| MHK | 5 | 0.464 * | 0.398 | 0.354 | 0.574 | −0.956 | 0.531 | 0.791 | 1.280 | 1.536 |

| MHK | 6 | −0.001 | 0.209 | −0.138 | 0.135 | −1.241 | −0.135 | −0.013 | 1.042 | 1.916 |

| RFMH | 7 | 0.819 * | 0.729 | 0.909 | 0.791 | 1.565 | 1.864 | 1.916 | 2.461 | |

| RFMH | 8 | 0.706 * | 0.047 | 0.634 | 0.778 | −0.232 | 0.744 | 0.916 | 1.187 | 1.774 |

| RFMH | 9 | 0.825 * | 0.055 | 0.719 | 0.930 | 1.536 | 2.038 | 2.113 | 2.312 | NA |

| RFMH | 10 | 0.832 * | 0.051 | 0.732 | 0.933 | 1.260 | 2.113 | 2.202 | NA | NA |

| RFMH | 11 | 0.709 * | 0.043 | 0.621 | 0.796 | 0.259 | 1.087 | 1.187 | 1.627 | 2.038 |

| RFMH | 12 | 0.534 * | 0.046 | 0.448 | 0.619 | −0.803 | −0.013 | 0.100 | 0.415 | 1.817 |

| MHK | 1 | 0.325 * | 0.204 | 0.445 | −0.502 | 0.722 | 0.970 | 1.482 | 1.660 | |

| MHK | 2 | 0.645 * | 0.439 | 0.524 | 0.765 | 0.214 | 1.536 | 1.817 | 1.973 | 2.113 |

| MHK | 3 | 0.650 * | 0.411 | 0.555 | 0.745 | −0.331 | 1.508 | 1.627 | 2.038 | 2.312 |

| MHK | 4 | 0.628 * | 0.384 | 0.513 | 0.743 | 0.453 | 1.733 | 1.817 | 1.973 | 2.038 |

| MHK | 5 | 0.464 * | 0.297 | 0.354 | 0.574 | −0.956 | 0.531 | 0.791 | 1.280 | 1.536 |

| RFMH | 7 | 0.819 * | 0.729 | 0.909 | 0.791 | 1.565 | 1.864 | 1.916 | 2.461 | |

| RFMH | 8 | 0.706 * | 0.068 | 0.634 | 0.778 | −0.232 | 0.744 | 0.916 | 1.187 | 1.774 |

| RFMH | 9 | 0.825 * | 0.078 | 0.719 | 0.930 | 1.536 | 2.038 | 2.113 | 2.312 | NA |

| RFMH | 10 | 0.832 * | 0.068 | 0.732 | 0.933 | 1.260 | 2.113 | 2.202 | NA | NA |

| RFMH | 11 | 0.709 * | 0.068 | 0.621 | 0.796 | 0.259 | 1.087 | 1.187 | 1.627 | 2.038 |

| RFMH | 12 | 0.534 * | 0.058 | 0.448 | 0.619 | −0.803 | −0.013 | 0.100 | 0.415 | 1.817 |

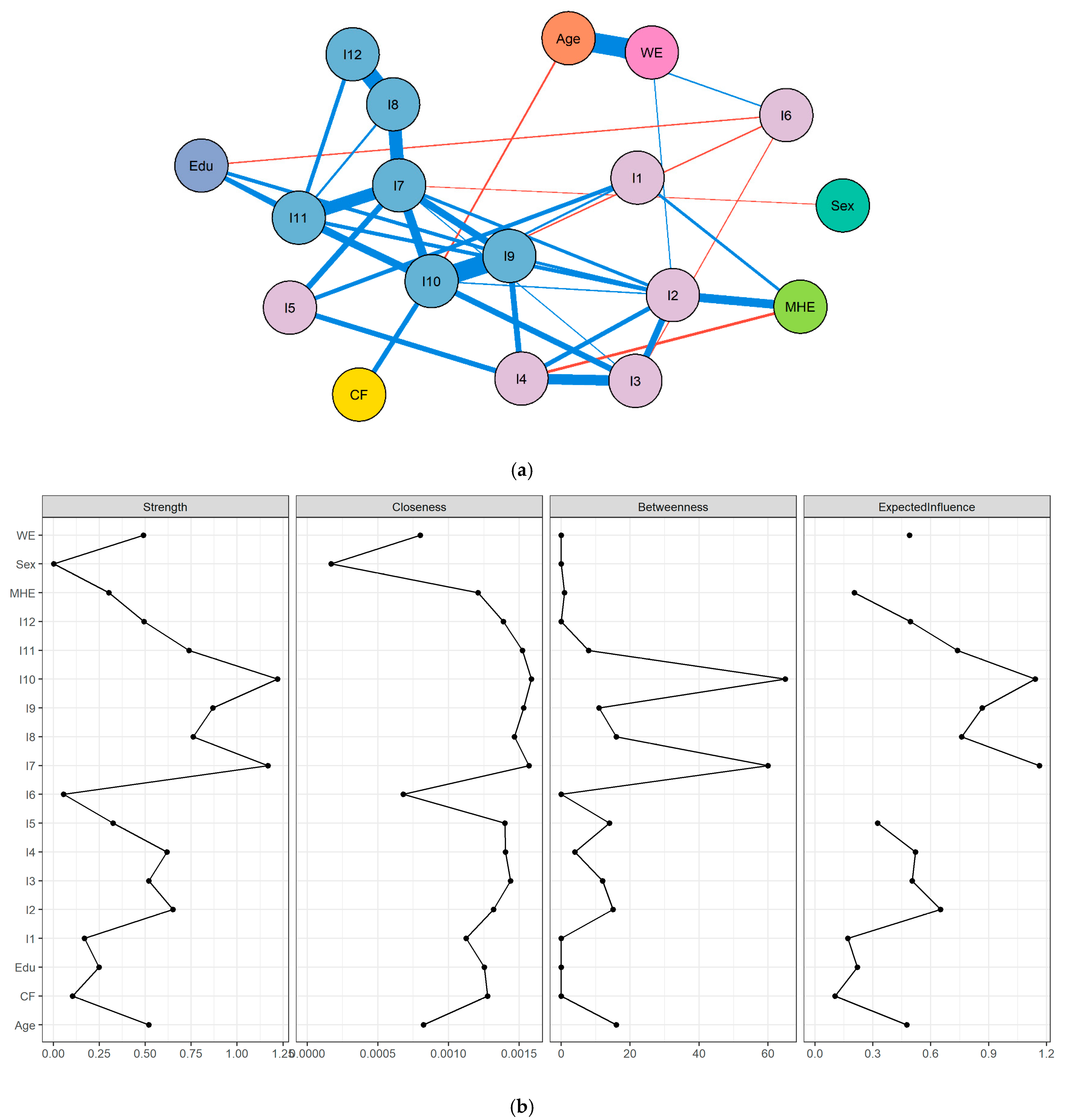

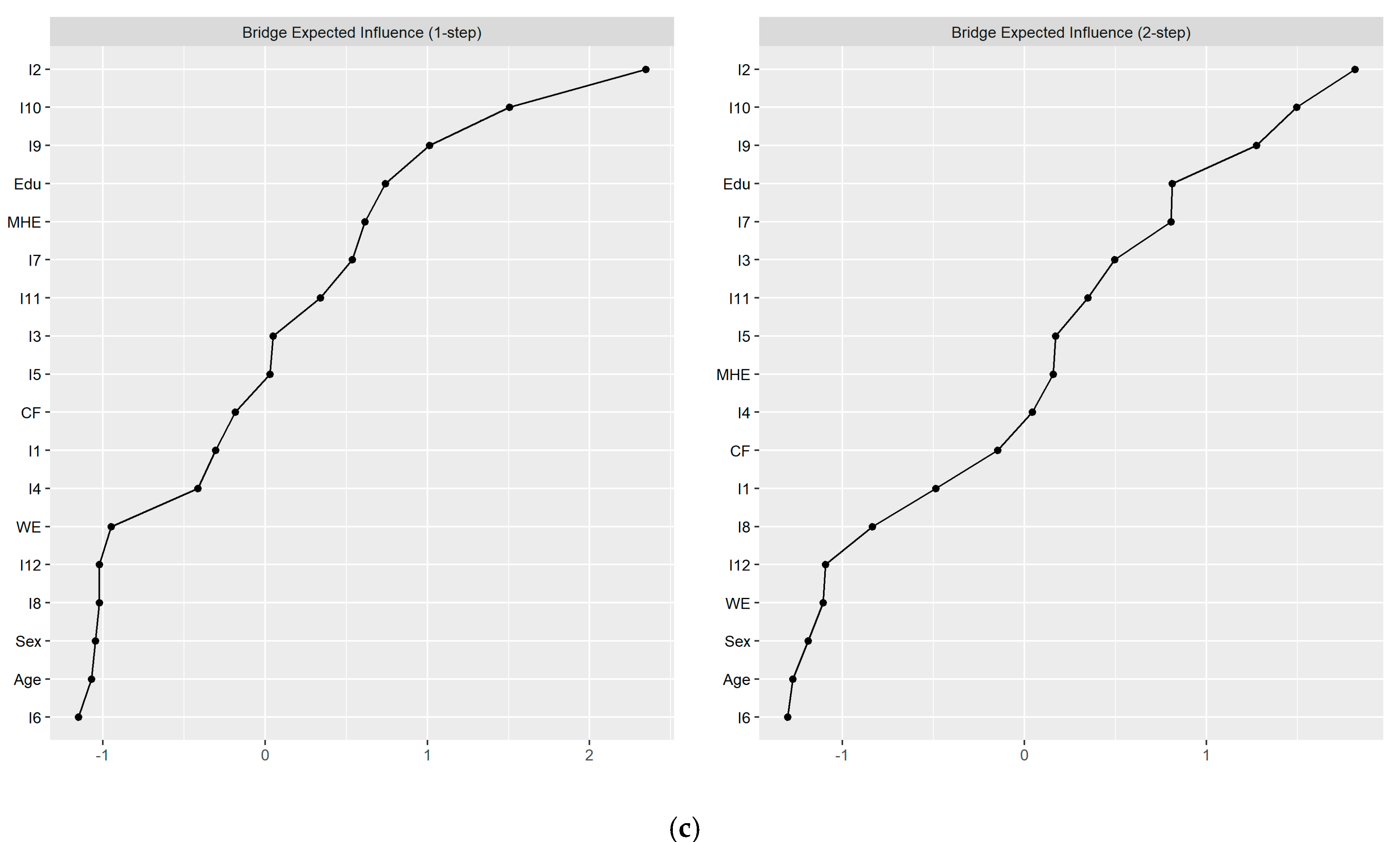

| V | S | B | C | EI | Bridge_EI1 | Bridge_EI2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 0.220 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.170 | 0.089 | 0.137 |

| I2 | 0.580 | 30 | 0.001 | 0.650 | 0.418 | 0.610 |

| I3 | 0.450 | 24 | 0.001 | 0.503 | 0.133 | 0.339 |

| I4 | 0.550 | 8 | 0.001 | 0.520 | 0.075 | 0.246 |

| I5 | 0.350 | 28 | 0.001 | 0.324 | 0.131 | 0.273 |

| I6 | 0.060 | 0 | 0.001 | −0.024 | −0.016 | −0.030 |

| I7 | 1.000 | 120 | 0.002 | 1.162 | 0.194 | 0.403 |

| I8 | 0.620 | 32 | 0.001 | 0.761 | 0.000 | 0.066 |

| I9 | 0.820 | 22 | 0.002 | 0.867 | 0.253 | 0.499 |

| I10 | 1.020 | 130 | 0.002 | 1.141 | 0.314 | 0.545 |

| I11 | 0.700 | 16 | 0.002 | 0.739 | 0.169 | 0.309 |

| I12 | 0.600 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.494 | 0.000 | 0.013 |

| Sex | 0.550 | 0 | 0.000 | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.007 |

| Age | 0.560 | 32 | 0.001 | 0.475 | −0.006 | −0.024 |

| Edu | 0.280 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.219 | 0.219 | 0.404 |

| WE | 0.780 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.490 | 0.009 | 0.010 |

| MHE | 0.470 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.203 | 0.203 | 0.270 |

| CF | 0.180 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.104 | 0.104 | 0.207 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moro, L.M.; Pontel, V.P.; Freitas, C.P.P.d.; Arteche, A.X.; Rocha, K.B. Adaptation and Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS-BR) in the Context of Primary Health Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121809

Moro LM, Pontel VP, Freitas CPPd, Arteche AX, Rocha KB. Adaptation and Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS-BR) in the Context of Primary Health Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121809

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoro, Larissa Moraes, Vinícius Perinetto Pontel, Clarissa Pinto Pizarro de Freitas, Adriane Xavier Arteche, and Kátia Bones Rocha. 2025. "Adaptation and Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS-BR) in the Context of Primary Health Care" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121809

APA StyleMoro, L. M., Pontel, V. P., Freitas, C. P. P. d., Arteche, A. X., & Rocha, K. B. (2025). Adaptation and Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS-BR) in the Context of Primary Health Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121809