Tooth Loss, Nutrition, and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Variables

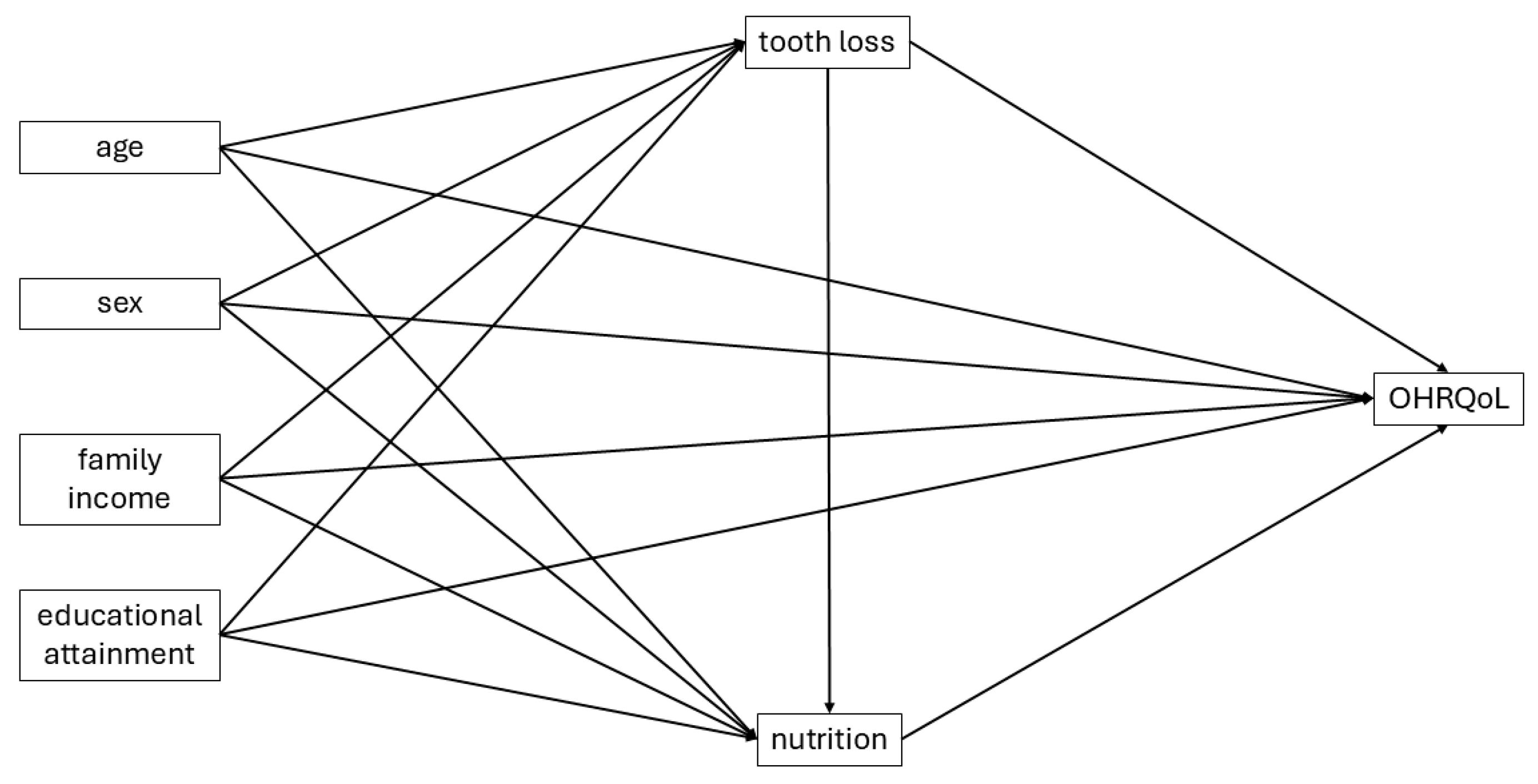

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atanda, A.J.; Livinski, A.A.; London, S.D.; Boroumand, S.; Weatherspoon, D.; Iafolla, T.J.; Dye, B.A. Tooth retention, health, and quality of life in older adults: A scoping review. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.L.; Park, M. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic oral health disparities among US older adults: Oral health quality of life and dentition. J. Public Health Dent. 2015, 75, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.E.; Song, H.Y.; Han, K.; Cho, K.H.; Kim, Y.H. Number of remaining teeth and health-related quality of life: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010–2012. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheiham, A.; Steele, J.G.; Marcenes, W.; Lowe, C.; Finch, S.; Bates, C.J.; Prentice, A.; Walls, A. The relationship among dental status, nutrient intake, and nutritional status in older people. J. Dent. Res. 2001, 80, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atchison, K.A.; Dolan, T.A. Development of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. J. Dent. Educ. 1990, 54, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.F.; Terada, A.S.; Vecchia, M.P.; Regis, R.R.; Zanini, A.P.; Compagnoni, M.A. Validation of the Brazilian versions of two inventories for measuring oral health-related quality of life of edentulous subjects. Gerodontology 2012, 29, e88–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodakowska, E.; Mierzyńska, K.; Bagińska, J.; Jamiołkowski, J. Quality of life measured by OHIP-14 and GOHAI in elderly people from Bialystok, north-east Poland. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenthöfer, A.; Ehret, J.; Zajac, M.; Kilian, S.; Rammelsberg, P.; Klotz, A.L. The Effects of Dental Status and Chewing Efficiency on the Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life of Nursing-Home Residents. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 2155–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesas, A.E.; Andrade, S.M.; Cabrera, M.A.; Bueno, V.L. Oral health status and nutritional deficit in noninstitutionalized older adults in Londrina, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2010, 13, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benksim, A.; Ait Addi, R.; Khalloufi, E.; Habibi, A.; Cherkaoui, M. Self-reported morbidities, nutritional characteristics, and associated factors in institutionalized and non-institutionalized older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.L.; Cheung, K.Y.; Lam, P.Y.P.; Gao, X.L. Oral Health Indicators for Risk of Malnutrition in Elders. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, R.A.; de Souza, L.B.; Corrente, J.E. Tooth loss and its relationship with protein intake by elderly Brazilians-A structural equation modelling approach. Gerodontology 2018, 35, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dye, B.A.; Weatherspoon, D.J.; Lopez Mitnik, G. Tooth loss among older adults according to poverty status in the United States from 1999 through 2004 and 2009 through 2014. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 9–23.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Bottenberg, P.; Conrads, G.; Eickholz, P.; Heasman, P.; Huysmans, M.C.; Lopez, R.; Madianos, P.; Müller, F.; Needleman, I.; et al. Dental caries and periodontal diseases in the ageing population: Call to action to protect and enhance oral health and well-being as an essential component of healthy ageing-Consensus report of group 4 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44 (Suppl. 18), S135–S144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brucki, S.M.; Nitrini, R.; Caramelli, P.; Bertolucci, P.H.; Okamoto, I.H. Suggestions for utilization of the mini-mental state examination in Brazil]. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2003, 61, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.I.M.; Caldas, P.R.; Cabral, E.D.; Lins, C.C.D.S.; Coriolano, M.D.G.W. Cognitive assessment instruments used in elderly Brazilians in the last five years. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2019, 24, 2513–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A.L.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Creugers, N.H.; Leal, S.C.; Frencken, J.E. The caries assessment spectrum and treatment (CAST) instrument: Its reproducibility in clinical studies. Int. Dent. J. 2014, 64, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheiham, A.; Steele, J.G.; Marcenes, W.; Tsakos, G.; Finch, S.; Walls, A.W. Prevalence of impacts of dental and oral disorders and their effects on eating among older people; a national survey in Great Britain. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2001, 29, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Nomura, T.; Sakurai, M.; Sugihara, N.; Yamanaka, S.; Matsukubo, T. Relationship between number of present teeth and nutritional intake in institutionalized elderly. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2005, 46, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.S.; Lauris, J.R.P.; Bastos, J.R.M.; Velasco, S.R.M.; Foger-Teixera, D.; Sá, L.M. The impacts of oral health-related quality of life of elderly people living at home: A cross-sectional study. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2021, 26, 1899–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelig, R.; Jones, V.M.; Touger-Decker, R.; Hoskin, E.R.; Singer, S.R.; Byham-Gray, L.; Radler, D.; Rothpletz-Puglia, P. The Eating Experience: Adaptive and Maladaptive Strategies of Older Adults with Tooth Loss. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2019, 4, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhuri, S.; Hegde, S.S.; Ravi, S.; Deepti, A.; Simpy, M. Comparison of chewing ability, oral health related quality of life and nutritional status before and after insertion of complete denture amongst edentulous patients in a Dental College of Pune. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2014, 24, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, N.M.; Gray-Donald, K.; Awad, M.A.; Johnson-Down, L.; Wollin, S.; Feine, J.S. Do implant overdentures improve dietary intake? A randomized clinical trial. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92 (Suppl. 12), 146S–153S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.S.; Sá, L.M.; Velasco, S.R.M.; Teixeira, D.F.; Paino, L.S.; Vettore, M.V. Frailty and oral health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. Braz. Oral Res. 2021, 35, e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradwel, S.; Sallam, A.; McCorry, N.; McEvoy, C.; Heilmann, A.; Lappin, C.; Ferrari, M.; Mitchell, G.; O’nEill, C.; Woodside, J.; et al. Nutrition and Oral Health in Care Homes: A qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives. J. Dent. 2025, 159, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.C.; Vargas, A.M.D.; Moura, R.N.V.; Fonseca, M.L.V.; Gomes, V.E.; Pinheiro, E.L.; Cartaxo, S.C.A.; Pinto, R.S. Caries and edentulism trends among Brazilian older adults: A comparative analysis of 2003, 2010, and 2023 surveys. Braz. Oral Res. 2025, 39 (Suppl. 1), e050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GOHAI > 0 | ||

|---|---|---|

| % | IC95% | |

| Age | ||

| 60–74 | 28.77 | 19.50–40.30 |

| 75+ | 20.51 | 10.50–36.20 |

| Sex | ||

| female | 25.84 | 17.70–36.00 |

| male | 26.09 | 12.10–47.50 |

| Minimum family income (MW) | ||

| <3 | 28.07 | 17.90–4.12 |

| 3+ | 23.64 | 14.20–23.67 |

| Educational attainment (in years) | ||

| ≥5 | 21.05 | 12.30–33.70 |

| <5 | 30.91 | 20.10–44.40 |

| tooth loss | ||

| <20 | 19.44 | 11.80–30.30 |

| ≥20 | 37.50 | 23.90–53.40 |

| Nutrition | ||

| normal | 29.17 | 19.80–40.80 |

| at risk | 20.59 | 10.10–37.50 |

| malnourished | 16.67 | 2.20–63.70 |

| Total | 25.89 | 18.60–34.90 |

| r | p | |

|---|---|---|

| GOHAI × MNA | −0.22 | 0.023 |

| tooth loss × MNA | −0.32 | 0.001 |

| GOHAI × tooth loss | −0.03 | 0.772 |

| Outcome | Predictor | Std. Beta | CI95% | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

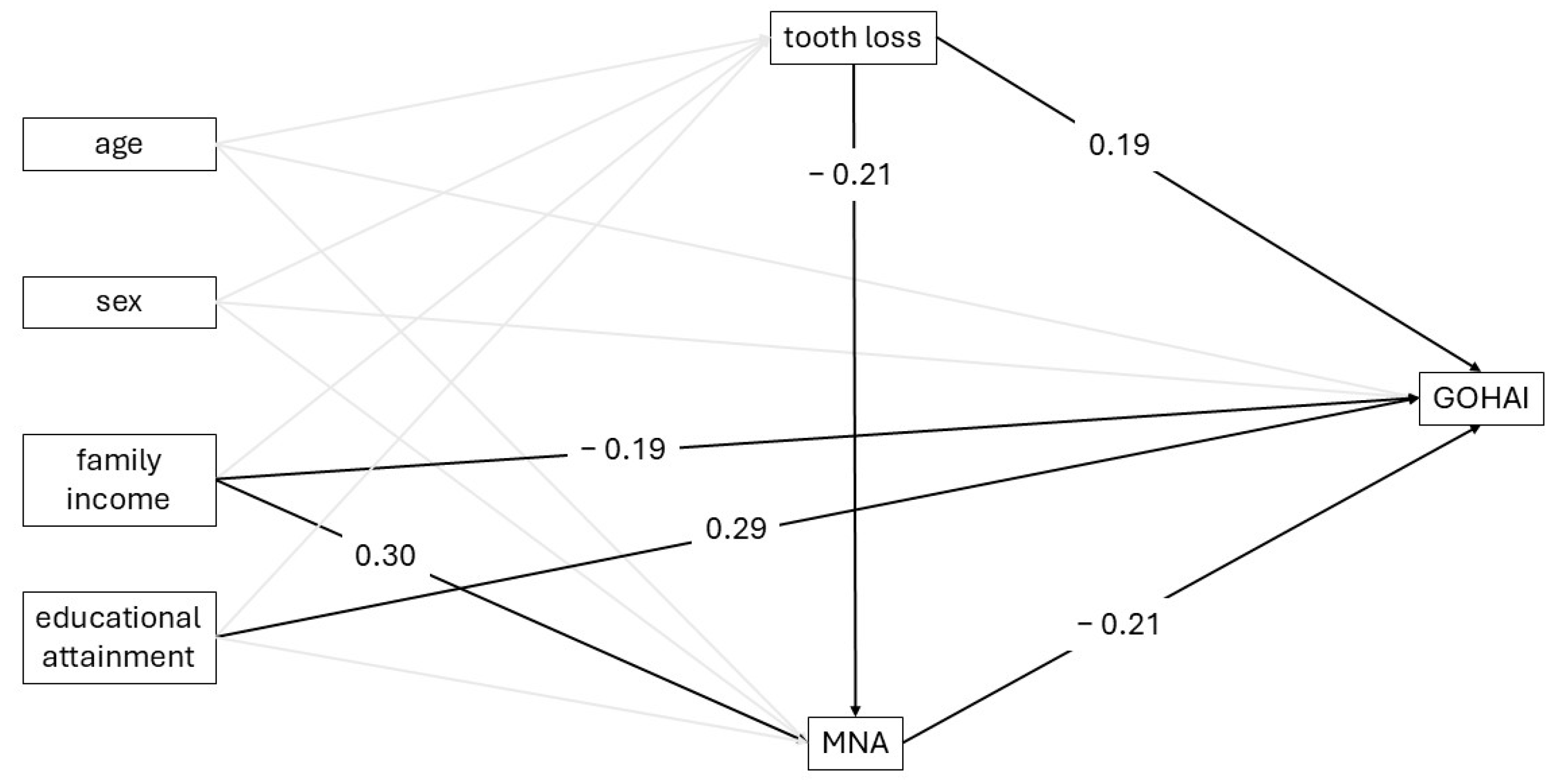

| MNA | tooth loss | −0.21 | −0.43 | 0.00 | 0.046 |

| age | −0.16 | −0.33 | 0.01 | 0.074 | |

| sex | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.26 | 0.194 | |

| family income | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.46 | 0.001 | |

| educational attainment | −0.10 | −0.32 | 0.13 | 0.398 | |

| constant | −0.22 | −0.55 | 0.12 | 0.201 | |

| GOHAI | MNA | −0.21 | −0.34 | −0.08 | 0.002 |

| tooth loss | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.023 | |

| age | −0.08 | −0.22 | 0.05 | 0.235 | |

| sex | −0.08 | −0.17 | 0.02 | 0.116 | |

| family income | −0.19 | −0.35 | −0.04 | 0.016 | |

| educational attainment | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.001 | |

| constant | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.003 | |

| Effect | Estimate | CI95% | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tooth loss → GOHAI (direct) | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.030 |

| tooth loss → GOHAI (indirect by MNA) | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.151 |

| tooth loss → GOHAI (total) | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.006 |

| Proportion mediated (PM) | 0.19 | −0.01 | 0.75 | 0.713 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Della Terra Mouco Garrido, B.; Pereira, P.S.S.; Foloni, K.; Pegoraro, H.D.; Souza, I.R.; Bastos, J.R.M.; Foratori-Júnior, G.A.; Yamauti, M.; Ferreira, R.C.; Bastos, R.S. Tooth Loss, Nutrition, and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121793

Della Terra Mouco Garrido B, Pereira PSS, Foloni K, Pegoraro HD, Souza IR, Bastos JRM, Foratori-Júnior GA, Yamauti M, Ferreira RC, Bastos RS. Tooth Loss, Nutrition, and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121793

Chicago/Turabian StyleDella Terra Mouco Garrido, Beatriz, Patrícia Soares Silva Pereira, Kamilly Foloni, Heloisa Dalberto Pegoraro, Isabelle Roldão Souza, José Roberto Magalhães Bastos, Gerson Aparecido Foratori-Júnior, Monica Yamauti, Raquel Conceição Ferreira, and Roosevelt Silva Bastos. 2025. "Tooth Loss, Nutrition, and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121793

APA StyleDella Terra Mouco Garrido, B., Pereira, P. S. S., Foloni, K., Pegoraro, H. D., Souza, I. R., Bastos, J. R. M., Foratori-Júnior, G. A., Yamauti, M., Ferreira, R. C., & Bastos, R. S. (2025). Tooth Loss, Nutrition, and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults: Evidence from a Structural Equation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121793