A Qualitative Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Evaluation of Innovative PrEP Delivery During COVID-19 Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in North West Province, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

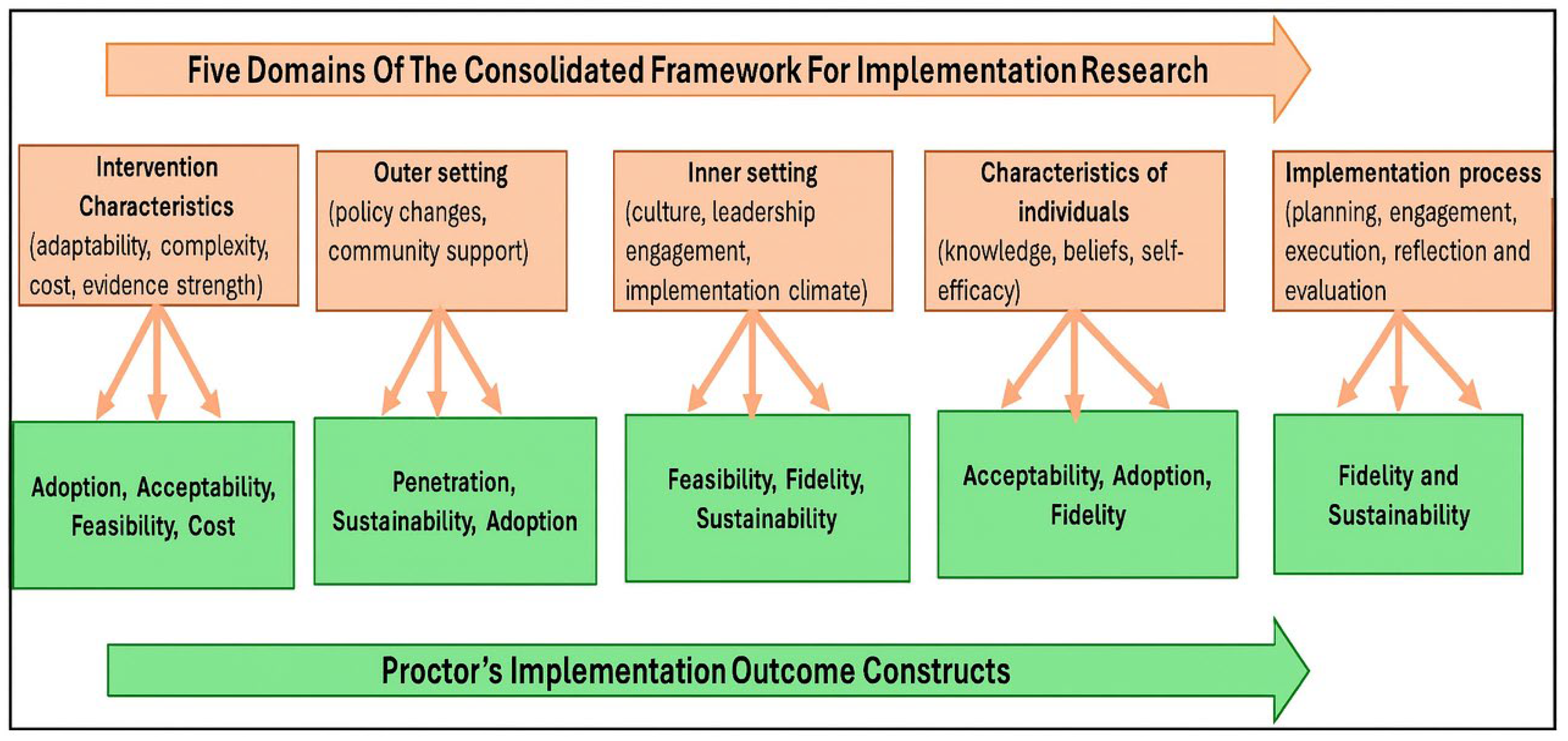

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Study Design and Setting

2.3. TB HIV Care Programme

2.4. Sampling and Size

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Trustworthiness

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

- Domain 1: Intervention characteristics (Adoption, Acceptability, Feasibility, Cost)

- 1.1.

- Sufficient mobile data bundles

“Our organisation provided us with enough data bundles every month, so we did not struggle with mobile data”(Stakeholder 1, female, 27 years old)

- 1.2.

- Existing media pages

“You see, sometimes it just depends on a person if she wants to live a healthy life, because we give them our contact details so that they can call/WhatsApp us anytime they need us”(Stakeholder 5, female, 50 years old)

- 1.3.

- Lack of mobile devices

“Not a lot of them remember our main challenge with our service users is that it is not common for they too have or own a mobile device for a long time, even though our tracing process is affected by this trend. Because some of them are drug users, if they need money, the first thing that will come to mind would be to sell their mobile devices”(Stakeholder 6, female, 37 years old)

- Domain 2: Outer setting (Penetration, Sustainability, and Adoption)

- 2.1.

- Mobile clinic vehicle

“My understanding is that most of them know us through our mobile clinic, cos now they can recognize us. Yeah, we did have our social media page for some time, so that assisted us throughout”(Stakeholder 2, male, 34 years old)

- 2.2.

- Fear of contracting COVID-19

“Eish, it was a struggle during those times because our clients did not want to meet with us because they were afraid of contracting COVID-19, and maybe the way we were dressed because we had to protect ourselves”(Stakeholder 4, female, 52 years old)

- 2.3.

- Low pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake

“In terms of PrEP services, they were also slow because, in places like taverns, where we would find them mostly, it was not easy due to restrictions like social distancing”(Stakeholder 7, male, 30 years old)

- Domain 3: Inner setting (Feasibility, Fidelity, Sustainability)

- 3.1.

- Teamwork

“But during our team’s meetings, some suggestions have been raised in the implementation of some methods that will improve adherence and retention to care of our service users”(Stakeholder 9, female, 31 years old)

- 3.2.

- Incorrect personal details

“Uhm… untraceable, for instance. You will find that the contact details are not working, relocation, because our service providers depend on business; if there are no clients, they move to other places, and some don’t provide us with information about their whereabouts”(Stakeholder 6, female, 37 years old)

- Domain 4: Characteristics of individuals (Acceptability, Adoption, Fidelity)

- 4.1.

- Clear communication channels

“Every Monday, we have a team meeting where we discuss our schedules for the week. For example, we have two mobile clinic Vans that we use for services, which are maintained by two groups, so we will discuss which group is going where and also the challenges that we had last week, so that we can assist one another”(Stakeholder 8, female, 33 years old)

- 4.2.

- Limited individual movements

“Yeah, I could say it did impact, I don’t want to say a lot, but it did make certain things a bit difficult because we couldn’t reach some of our service users, it was hard to get them given the fact that through certain stages certain people can’t come out things were so limited”(Stakeholder 1, female, 27 years old)

- Domain 5: Implementation process (Fidelity and Sustainability)

- 5.1.

- Stakeholders’ resilience

“Yoh, what can I say, we really tried to maintain services and learn to adapt as much as we could because we were worried that our organisation would close. So, we kept on pushing ourselves to recruit new clients and retain the old ones into care”(Stakeholder 10, female, 37 years old)

- 5.2.

- Lack of communication

“But some are committed to their treatment because they would call us to inform us that they moved, and then we can refer/link them to our nearby TB HIV Care, to where they are, because we also have branches in other areas too”(Stakeholder 11, female, 47 years old)

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SAMRC | South African Medical Research Council |

| PACER | Pan African Centre for Epidemics Research |

| CFIR | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

| PrEP | Pre-exposure prophylaxis |

| AGYW | Adolescent girls and young women |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| RE-AIM | Reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance |

| EPIS | Exploration, preparation, implementation, and sustainment |

| UJREC | University of Johannesburg Research Ethics Committee |

| NW | North West |

References

- Low, L. One in Four People with HIV Are Not on Treatment, According to New Estimates. Spotlight. 4 April 2024. Available online: https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/2024/04/04/one-in-four-people-with-hiv-not-on-treatment-according-to-new-estimates/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Celum, C.L.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Baeten, J.M.; van der Straten, A.; Hosek, S.; Bukusi, E.A.; McConnell, M.; Barnabas, R.V.; Bekker, L.G. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women in Africa: From efficacy trials to delivery. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clinical Guidelines for PrEP. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hivnexus/hcp/prep/index.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Department of Health, South Africa. Updated Guidelines for the Provision of Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (Prep) to Persons at Substantial Risk of HIV Infection 2021. Updated Guidelines PrEP Final. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/elibdownloads/2022-08/PrEP%20Guidelines%20Update%2012%20%20Nov%20%202021%20Final.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- MacDonald, J.; Estcourt, C.S.; Flowers, P.; Nandwani, R.; Frankis, J.; Young, I.; Clutterbuck, D.; Dalrymple, J.; McDaid, L.; Steedman, N.; et al. Improving HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence and retention in care: Process evaluation and recommendation development from a nationally implemented PrEP programme. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, E.; Katz, A.W.; O’Rourke, S.; Bekker, L.G.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Bukusi, E.; Travill, D.; Omollo, V.; Morton, J.F.; O’Malley, G.; et al. Adolescent girls and young women’s PrEP-user journey during an implementation science study in South Africa and Kenya. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhumuza, R.; Ssemata, A.S.; Kakande, A.; Ahmed, N.; Atujuna, M.; Nomvuyo, M.; Bekker, L.G.; Dietrich, J.J.; Tshabalala, G.; Hornschuh, S.; et al. Exploring perceived barriers and facilitators of PrEP uptake among young people in Uganda, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.G.; Coats, C.S.; Adams, E.; Murphy, M.; Stewart, C.; Arnold, T.; Chan, P.A.; Nunn, A. Development of telemedicine infrastructure at an LGBTQ+ clinic to support HIV prevention and care in response to COVID-19, Providence, RI. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 2743–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.; Chikwari, C.D.; McHugh, G.; Koris, A.; Bandason, T.; Dauya, E.; Mapani, L.; Abrahams, M.; Shankland, L.; Simms, V.; et al. Feasibility and usability of Mobile Technology to assist HIV Self-Testing in Youth in Zimbabwe: A mixed-methods study. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 73, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, D.; Fowler, C.; Bergh, K.; Mathebula, M.; Mathews, C. Process Evaluation of the Combination HIV Prevention Intervention for Adolescent Girls and Young Women, Global Fund Grant Period 2019 to 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.samrc.ac.za/sites/default/files/attachments/2022-09/Report_Implementation_Lead%26Management.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Patel, P.; Kerzner, M.; Reed, J.B.; Sullivan, P.S.; El-Sadr, W.M. Public health implications of adapting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis programs for virtual service delivery in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e37479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutyambizi, C.; Dunlop, J.; Maluleke, C.; Ranoto, L.; Chetty, T.; Ndou, R.; Struthers, H.; McIntyre, J.A.; Rees, K. Effect of COVID-19 on HIV, tuberculosis, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV indicators in Mopani district, South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2021, 111, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginindza, M.B.; Ncube, N.; Coetzee, R. COVID-19 impact on HIV PrEP uptake and retention at selected health facilities in Eswatini. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2024, 16, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.; Rucinski, K.; Jarrett, B.A.; Ackerman, B.; Wallach, S.; Marcus, J.; Adamson, T.; Garner, A.; Santos, G.M.; Beyrer, C.; et al. Perceived interruptions to HIV prevention and treatment services associated with COVID-19 for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in 20 countries. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2021, 87, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, K. Using social media for telemedicine during the COVID-19 epidemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 46, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Denali, D.L. Social media in health education, promotion, and communication: Reaching rural Hispanic populations along the USA/Mexico border region. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2014, 1, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwelunmor, J.; Nwaozuru, U.; Obiezu-Umeh, C.; Uzoaru, F.; Ehiri, J.; Curley, J.; Ezechi, O.; Airhihenbuwa, C.; Ssewamala, F. Is it time to RE-AIM? A systematic review of economic empowerment as HIV prevention intervention for adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa using the RE-AIM framework. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2020, 1, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcone, A.I.; Coyle, K.; Butame, S.; Harper, G.W.; Aarons, G.A.; Naar, S. Using the Exploration-Preparation-Implementation-Sustainment (EPIS) Framework to prepare for the implementation of evidence-based practices into adolescent HIV settings. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 4093–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brant, A.R.; Dhillon, P.; Hull, S.; Coleman, M.; Ye, P.P.; Lotke, P.S.; Folan, J.; Scott, R.K. Integrating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis into family planning care: A RE-AIM framework evaluation. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2020, 34, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, W.F.; Canan, C.E.; Knight, S.; Waldman, A.L.; Dillingham, R.; Ingersoll, K.; Schexnayder, J.; Flickinger, T.E. An implementation strategy to expand mobile health use in HIV care settings: Rapid evaluation study using the consolidated framework for implementation research. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e19163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, R.E.; Crosson, J.C.; O’Malley, A.S.; Cromp, D.; Taylor, E.F. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: A rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TB HIV Care. Our History. 2025. Available online: https://tbhivcare.org/our-history/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Janari, L. TB HIV Care 2020 Annual Report. 31 March 2020. Available online: https://tbhivcare.org/annual-reports/#flipbook-2020/1/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- TB HIV Care. Changing Lives Through Our Programmes. 2025. Available online: https://tbhivcare.org/project/key-populations/# (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Rahimi, S. Saturation in qualitative research: An evolutionary concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olifant, L.L.; Phalane, E.; Mhlophe, H.; Phaswana-Mafuya, R.N. Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Innovative Interventions Implemented During COVID-19 Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in North-West Province of South Africa. COVID 2025, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Kahle, E.M.; Christiani, Y.; Suryani, S. Utilization of social media for the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS: A scoping review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 2443–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, E.; Ojukwu, E.; Hirani, S.; Sotindjo, T.; Okedo-Alex, I.; Magagula, P. How the COVID-19 pandemic influenced HIV care: Are we prepared enough for future pandemics? An assessment of factors influencing access, utilization, affordability, and motivation to engage with HIV services amongst African, Caribbean, and Black women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nematswerani, N.; Steenkamp, L.; Haneef, S.; Naidoo, R.M.; Fonn, S. Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare services for adults during three waves of COVID-19 infections: A South African private sector experience. S. Afr. Med. J. 2023, 113, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagat, H.; Sharma, M.; Kariithi, E.; Otieno, G.; Katz, D.; Masyuko, S.; Mugambi, M.; Wamuti, B.; Weiner, B.; Farquhar, C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV testing and assisted partner notification services, Western Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 3010–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuier, E.A.; Kolko, D.J.; Aarons, G.A.; Schachter, A.; Klem, M.L.; Diabes, M.A.; Weingart, L.R.; Salas, E.; Wolk, C.B. Teamwork and implementation of innovations in healthcare and human service settings: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2024, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.M.; Hall, E.; Im, V.; Lee, C.A.; Park, S. Disruptions to HIV services due to the COVID pandemic in the USA: A state-level stakeholder perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.; Leslie, H.H.; Mabetha, D.; Becker, N.; Kahn, K.; Lippman, S.A. Applying CFIR to assess multi-level barriers to PrEP delivery in rural South Africa: Processes, gaps and opportunities for service delivery of current and future PrEP modalities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 361, 117370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, S.; Sweeney, A.; Li, Q.; Watson, D.L.; Bauermeister, J.; Hernandez, B.; Williams, J.; Brady, K.A. Facilitators and Barriers to Equitable Implementation of Telehealth PrEP Delivery: A Qualitative Descriptive Study of Program Staff and Stakeholders. Health Promot. Pract. 2025, 19, 15248399251347253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.E.; Hanif, H.; Stocks, J.B.; Rochelle, A.E.; Dominguez, K.; Armora Langoni, E.G.; Reyes, H.L.; Doncel, G.F.; Muessig, K.E. Mobile Health Intervention Tools Promoting HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2025, 13, e60819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson-Gibson, M.; Ezema, A.U.; Orero, W.; Were, I.; Ohiomoba, R.O.; Mbullo, P.O.; Hirschhorn, L.R. Facilitators and barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake through a community-based intervention strategy among adolescent girls and young women in Seme Sub-County, Kisumu, Kenya. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, S.; Aase, K.; Billett, S.; Canfield, C.; Røise, O.; Njå, O.; Guise, V.; Haraldseid-Driftland, C.; Ree, E.; Anderson, J.E.; et al. Defining the boundaries and operational concepts of resilience in the resilience in healthcare research program. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ciaccio, M.; Lorente, N.; Villes, V.; Maxence, A.A.; Pelaez, C.M.; Guillen, J.R.; Castillo, I.; Folch, C.; Diagne, R.; Riegel, L.; et al. Resilience outcomes and associated factors among workers in community-based HIV care centres during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country analysis from the EPIC program. Health Policy OPEN 2023, 5, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, E.; Sikkema, K.J.; Julies, R.F.; Mazer, K.; O’Malley, G.; Heffron, R.; Morton, J.F.; Johnson, R.; Celum, C.; Baeten, J.M.; et al. Exploring adolescent girls and young women’s PrEP-user profiles: Qualitative insights into differentiated PrEP delivery platform selection and engagement in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2024, 27, e26254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, L.; Mudzingwa, E.K.; Fynn, L.; Atujuna, M.; Mugore, M.; Gandhi, M.; Celum, C.; Hosek, S.; Bekker, L.G.; Daniels, J.; et al. Factors that influence adolescent girls and young women’s re-initiation or complete discontinuation from daily oral PrEP use: A qualitative study from Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2023, 26, e26175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CFIR Domain | Implementation Constructs | Semi-Structured Interview Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention characteristics | Adoption, Acceptability, Feasibility, Cost | How did you perceive the implemented social media platforms for PrEP service continuity during the lockdown period? Were service users able to access them? Were there any extra resources to be added? |

| Outer setting | Penetration, Sustainability, Adoption | Were the interventions successful in reaching the target population? If not, what was the reason for this? |

| Inner setting | Feasibility, Fidelity, Sustainability | Were you able to implement these innovative PrEP interventions as planned? If not, why? |

| Characteristics of individuals | Acceptability, Adoption, Fidelity | Were you equipped efficiently to adapt the implemented innovative interventions into PrEP services? |

| Implementation process | Fidelity, Sustainability | If these innovative interventions were implemented as planned, are there any indicators suggesting that the intervention has the potential to be sustained? |

| Stakeholders | Age (Years) | Gender | Roles | Length of Service (Years) | Highest Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder 1 | 27 | Female | Case manager | 7 | Secondary |

| Stakeholder 2 | 30 | Male | Driver | 2 | Tertiary |

| Stakeholder 3 | 31 | Female | General assistant | 1 | Secondary |

| Stakeholder 4 | 31 | Female | Nurse | 2 | Tertiary |

| Stakeholder 5 | 33 | Female | Nurse | 2 | Tertiary |

| Stakeholder 6 | 34 | Male | Driver/counsellor | 7 | Tertiary |

| Stakeholder 7 | 37 | Female | Social worker | 6 | Tertiary |

| Stakeholder 8 | 37 | Female | Data capturer | 7 | Tertiary |

| Stakeholder 9 | 44 | Female | Peer educator | 4 | Secondary |

| Stakeholder 10 | 47 | Female | Peer coordinator | 6 | Secondary |

| Stakeholder 11 | 50 | Female | Peer educator | 4 | Secondary |

| Stakeholder 12 | 52 | Female | Peer educator | 2 | Secondary |

| CFIR Five Domains | Implementation Outcomes | Implemented Innovations | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention characteristics | Adoption, Acceptability, Feasibility, Cost | Sufficient mobile data | |

| Facebook pages | Existing media pages | ||

| Telemedicine | |||

| Outer setting | Penetration, Sustainability, and Adoption | Mobile clinic vehicle | |

| Facebook pages | |||

| Telemedicine | |||

| Inner setting | Feasibility, Fidelity, Sustainability | Teamwork | |

| Facebook pages | |||

| Telemedicine | |||

| Characteristics of individuals | Acceptability, Adoption, Fidelity | Clear communication channels | |

| Facebook pages | |||

| Telemedicine | |||

| Implementation process | Fidelity, Sustainability | Stakeholders’ resilience | |

| Facebook pages | |||

| Telemedicine |

| CFIR Domain | Implementation Outcomes | Implemented Innovations | Key Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention characteristics | Adoption, Acceptability, Feasibility, Cost | WhatsApp Facebook pages Telemedicine | Lack of mobile devices |

| Outer setting | Penetration, Sustainability, Adoption | WhatsApp Facebook pages Telemedicine | Fear of contracting COVID-19 Low PrEP uptake |

| Inner setting | Feasibility, Fidelity, Sustainability | WhatsApp Facebook pages Telemedicine | Incorrect personal information |

| Characteristics of individuals | Acceptability, Adoption, Fidelity | WhatsApp Facebook pages Telemedicine | Limited individual movement |

| Implementation process | Fidelity, Sustainability | WhatsApp Facebook pages Telemedicine | Lack of regular communication |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olifant, L.L.; Phalane, E.; Shiferaw, Y.A.; Mhlophe, H.; Phaswana-Mafuya, R.N. A Qualitative Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Evaluation of Innovative PrEP Delivery During COVID-19 Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in North West Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101602

Olifant LL, Phalane E, Shiferaw YA, Mhlophe H, Phaswana-Mafuya RN. A Qualitative Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Evaluation of Innovative PrEP Delivery During COVID-19 Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in North West Province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101602

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlifant, Lerato Lucia, Edith Phalane, Yegnanew A. Shiferaw, Hlengiwe Mhlophe, and Refilwe Nancy Phaswana-Mafuya. 2025. "A Qualitative Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Evaluation of Innovative PrEP Delivery During COVID-19 Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in North West Province, South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101602

APA StyleOlifant, L. L., Phalane, E., Shiferaw, Y. A., Mhlophe, H., & Phaswana-Mafuya, R. N. (2025). A Qualitative Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Evaluation of Innovative PrEP Delivery During COVID-19 Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in North West Province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101602