Prevention of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Illicit Drug Use Among Youth: A Scoping Review of European School-Based Programs with Insights on Mental Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Program Characteristics and Delivery

1.1.1. Preventure

1.1.2. Unplugged

1.1.3. IPSYcare

1.2. Objective

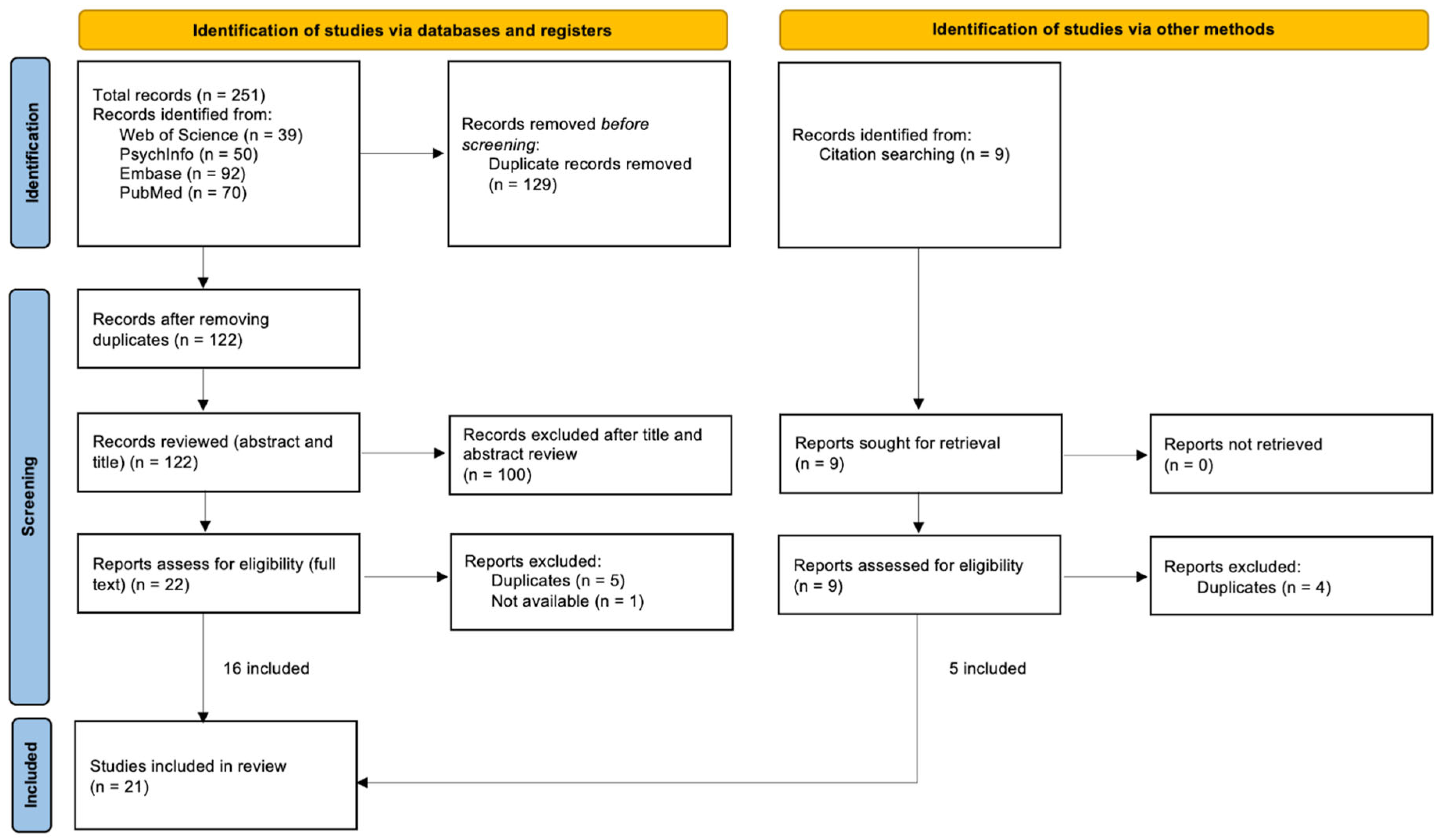

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Overall Characteristics

3.2. Program Implementation and Study Design

3.2.1. Preventure

3.2.2. Unplugged

3.2.3. IPSYcare

3.3. Program Effectiveness

3.3.1. Preventure

3.3.2. Unplugged

3.3.3. IPSYcare

| Program | Characteristics | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Preventure |

|

|

| Unplugged |

|

|

| IPSYcare |

|

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Temporal Effects

4.2. Mediating Factors

4.3. Relationship Between Effectiveness and Program Characteristics

4.4. Target Groups and Mechanism of Behavioural Change

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Title | Authors | Program | Country | Scope | Gender | Age | Changes acc to Context | Outcomes | Anything Interesting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience factors, the school-based universal prevention program ‘Unplugged’ and healthy behavior among early adolescents | Abrinkova, L., Orosova, O., Neves De Jesus, S., Gajdosova, B., Bacikova-Sleskova, M. [21]. | Unplugged | Slovakia | Alcohol, Tobacco | Total population: 425 participants (242 in the experimental group); 204 males and 221 females. | 7th-grade students (mean age = 13.5) | The Unplugged program was implemented by teachers who completed a three-day training course. The implementation did not follow a strict time plan but depended on the availability and resources of each school individually. | Unplugged participation increased the likelihood of being a non-user and reduced the risk of becoming a new user (Unplugged has a protective effect against early-onset substance abuse). | Community environment is not associated with substance abuse among young adolescents. Higher self-esteem was significantly associated with a higher probability of being a non-user early adolescent. Being a female increased the probability of being a non-user adolescent when compared to males. |

| A Systematic Review of School-Based Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention Programs | Roberta Agabio, Giuseppina Trincas, Francesca Floris, Gioia Mura, Federica Sancassiani, Matthias C. Angermeyer [22]. | Unplugged, SUCCESS, Adventure, CHOICE, Internet-based intervention, Media-based, P.A.T.H.S | Study 1—7 European countries, Study 2—Czech Republic, Study 3—7 European countries | Unplugged study 1—Alcohol, Alcohol related problems. 2. Unplugged study 2—Alcohol, Tobacco, Cannabis. 3. Unplugged study 3—Alcohol and other drugs | Study 1: Total population (7079): Females—3504 (49%); Males—3575 (51%). Study 2: Total population (1753): Females—859 (49%); Males—894 (51%). Study 3: Total population (6370): Females—3058 (48%); Males—3312 (52%) | Study 1: Ages 12–14 years; Study 2: Ages 11–13 years; Study 3: Mean age = 13.2 years. | Not reported | In one study, participation in Unplugged (compared with a control group that received usual health education) had a decreased risk of reporting alcohol-related problems. Moreover, non-drinkers and occasional drinkers progressed towards frequent drinking less. In study 3 there was a reduction (although marginal) in daily smoking, frequent smoking, and frequent cannabis use when compared to the control. | In Europe, the Unplugged program was the most evidence-based substance use prevention program |

| Effectiveness of a Selective, Personality-Targeted Prevention Program for Adolescent Alcohol Use and Misuse: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Conrod P.J., O’Leary-Barrett M., Newton N., Topper L., Castellanos-Ryan N., MacKie C. [15]. | Preventure | United Kingdom | Alcohol | Total population: 2643 participants; High-risk (HR)—1210; Low-risk (LR)—1433. | Year 9 students (mean age = 13.7 years); follow-ups at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. | Not reported | Significant reductions in rates of drinking, frequency of binge drinking, and problem drinking symptoms among high-risk adolescents. Indirect ‘herd effects’ were observed among low-risk adolescents as well as reduced binge drinking rates. | |

| The effect of contextual risk factors on the effectiveness of brief personality-targeted interventions for adolescent alcohol use and misuse: A cluster-randomized trial | Edalati, H., Afzali, M. H., Castellanos-Ryan, N., & Conrod, P. J. [16]. | Preventure | United Kingdom | Alcohol | Intent to treat (final) pop: 1129 | Not reported | Higher socioeconomic status (SES) adolescents had higher initial levels of alcohol use and related harm. However, they responded to the intervention just as effectively as those from lower SES and equally benefited from it. | Personality-targeted interventions proved effective for at-risk adolescents, even when peer victimisation went unnoticed by teachers or parents, highlighting a protective effect for this vulnerable group. | |

| Sex specific trajectories in cigarette smoking behaviours among students participating in the Unplugged school-based randomized control trial for substance use prevention | Gabrhelik, R., Duncan, A., Lee, M. H., Stastna, L., Furr-Holden, C. D. M., & Miovsky, M. [26]. | Unplugged | Czech Republic | Tobacco | Baseline: 944 males and 929 females (total population = 1874). Final follow-up: 906 males and 855 females (total population = 1871). | Baseline: Mean age = 11.8 years. Final follow-up: Mean age = 14.5 years. | Not reported | Useful for slow escalators independently of sex, not useful for rapid to moderate escalators independently of sex. | Identified two types of adolescent tobacco smokers: slow escalators and rapid moderate escalators. Distinguish between them, as the speed of progression is an indicator of nicotine addiction and heavy smoking progression. |

| Short-Term Mediating Factors of a School-Based Intervention to Prevent Youth Substance Use in Europe | Fabrizia Giannotta, Federica Vigna-Taglianti, Maria Rosaria Galanti, Maria Scatigna, Fabrizio Faggiano [28]. | Unplugged | Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Sweden | Alcohol, Tobacco, Cannabis | Pre-test: 7079 students; Post-test: 6370 students (3057 females and 3312 males). | Mean age 13.25 years old | Not reported | Reduced cigarrete smoking, drunkness, and cannabis use. | Similarities in the mediating mechanisms for tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use. |

| Prevention versus pseudo-prevention: A systematic review of school drug prevention and its indexing in best practice portals | Jorge Medina Martinez, Víctor José Villanueva-Blasco [29]. | Unplugged | Spain | Alcohol, Tobacco, Cannabis, Marijuana | - | School age | Not reported | Unplugged efficient and recommended | |

| The effect of the school-based unplugged preventive intervention on tobacco use in the Czech Republic | Miovsky, M., Novak, P., Stastna, L., Gabrhelik, R., Jurystova, L., & Vopravil, J. [30]. | Unplugged | Czech Republic | Tobacco | 1874 Students: 952 males 922 females | Mean age 11.8 years old | Not reported | Unplugged is useful for slower progression to increased smoking but not statistically significant in the long term. | |

| The impact of youth internalising and externalising symptom severity on the effectiveness of brief personality-targeted interventions for substance misuse: A cluster randomised trial | Perrier-Ménard, Eveline;Castellanos-Ryan, Natalie;O’Leary-Barrett, Maeve;Girard, Alain;Conrod, Patricia J. [17]. | Preventure | United kningdom | Alcohol | 1025 students: 553 males 472 females | Mean age 13.7 years old | Not reported | Prevention is effective in reducing substance misuse in a two-year period in youth at particularly high risk for addiction and mental health problems. | |

| Translation of Etiology into Evidence-Based Prevention: The Life Skills Program IPSY | Karina Weichold [9]. | IPSY | Germany (replication in Italy and Austria) | Alcohol and Tobacco | Pilot test: 105 participants (including pre- and post-test design; no gender specified). Large-scale study: approximately 1700 participants (no gender specified). The program was also tested on subgroups that included gender, but specific numbers were not provided in the review. | Ages 10.5–13 years (Grades 5 to 7) | Pilot test: the training manual has been revised slightly, mostly in a matter of time lines (based on the feedbacks of the teachers) | Outcome of pilot test: Need of a teacher-based implementation Outcome Large scale: IPSY seemed to have a positive effect on the prevalence, frequency of use and amount of use of alcohol and cigarettes. It’s effective to prevent early and high use of both substances. Compared to the control group, students who have followed the intervention program have had their general life skills and substance-specific competencies (e.g., resistance skills) increased. Both girls and boys profited from a positive effect on school bonding, general life skills and substance use. Girls have demonstrated a positive effect on communication competencies (effective communication and knowledge about self-confidence), but not boys. In this way, IPSY enables girls to strengthen their self-confidence and confidence in social interactions, which tend to diminish during early and middle adolescence. Outcome in the replication (Italy and Austria): IPSY targets universal risk and protective factors such as low adherence to social norms, influence from peers engaging in risky behaviours, or weak connections to structured developmental environments. IPSY can be effectively implemented in any cultural context. | 687 students were non-white, but there is no analysis to differentiate the effects on white and Black populations. |

| Long-Term Effects of the Life Skills Program IPSY on Substance Use: Results of a 4.5-Year Longitudinal Study | Karina Weichold, Anja Blumenthal [8]. | IPSY | Germany | Alcohol, tobacco and illicit substances | Gender not specified (all results did not change when controlling for the gender variable) Differents timing corresponding to the follow-ups: T1: 1657 T2: 1419 T3: 1278 T4: 1131 T5: 1014 T6: 685 | Ages 10.5–15 years (Grades 5 to 7, with follow-ups in Grades 8 and 9). | not reported | Significant long-term effect on frequency of smoking cigarettes (less frequently) and proneness to cannabis and ecstasy use (less prone). Positive effect on alcohol consumption but only for a short term; during the 2 years following the end of the programme intervention, it starts to decrease again. | Even though it didn’t help for the alcohol consumption, the results show that participants of the intervention group drink alcohol not as much as a coping mechanism as the control group. In addition, later onset of alcohol use reduces the risk of addiction during adulthood (=lifetime benefit of the intervention). The high consumption of alcohol in Germany is part of their highly normative behaviour in mid-adolescence, when drugs and cigarettes are less accepted in the society for young people. The effectiveness of this program seemed to be higher when combined with prevention strategies involving families or other social contexts of youth. |

| The life skills program IPSY: Positive influences on school bonding and prevention of substance misuse | Victoria Wenzel, Karina Weichold, Rainer K. Silbereisen [10]. | IPSY | Germany | Alcohol | N = 952 (54% female, 46% male)—number of students who completed both pre- and post-tests, as well as the follow-ups in Grades 6 and 7. Attrition was mainly due to schools withdrawing from the intervention for logistical reasons, or students changing schools or being absent due to illness. | Ages 10.5–13 years (Grades 5 to 7) | Alcohol use was measured at 4 intervals (pre-test=t1, post-test=t2, and then at the end of year 6=t3 and year 7=t4). Students were first asked to report their general alcohol consumption frequency over the previous 30 days using a scale ranging from 0/5 (0 being never and 5 being daily). Students were then asked to specify their previous alcohol consumption in the last 30 days for various types of beverages (beer, wine, mixed drinks, and spirits) as well as their future expectations regarding alcohol use within the next 12 months. In this study, although the school is not an explicit target of an LSP, the role of the bond that the school provides in the effectiveness of an LSP is analysed to determine whether it has an effect on alcohol misuse among young people | IPSY has a positive long-term effect on antecedents such as the intention to consume alcohol and on their actual consumption rate of alcohol. The positive influences on school bonding following program participation were found to partially mediate the intervention effects on alcohol use. Participating in this program reinforced their bond with school, which in return participated in a lower alcohol misuse behaviour. | IPSY has good timing in terms of implementation because it starts before the substance use is likely to occur (approx. between 12 and 14 in Germany) and before regular consumption patterns develop. The authors explained that IPSY’s declining impact on alcohol use is likely due to cultural factors in Germany surrounding alcohol’s social acceptability during mid-adolescence, making it difficult for school-based prevention alone to maintain effects beyond early adolescence. In contrast, tobacco and illicit drugs remain less socially accepted, which may explain IPSY’s longer-lasting protective outcomes. Students who completed IPSY also showed lower coping motives for drinking in that they were less likely to report using alcohol to manage stress or negative feelings, suggesting that IPSY had enduring effects on the psychological reasons for drinking even after use levels equalised with controls. Later booster sessions or integrating it with family- or community-based strategies were recommended by authors to sustain alcohol-related prevention gains over time. |

| Peers and Teachers as Facilitators of the Life Skills Program IPSY—Results from a Pilot Study | Karina Weichold, Rainer K. Silbereisen [11]. | IPSY | Germany | Alcohol and Tobacco | Pilot study: 105 students (46 female, 59 male) | Ages 10.74–13 years (Grades 5 to 7) | The program was delivered either by teachers or by older peers (11th graders). Teacher-led implementation showed high fidelity (90% of manual content delivered), while peer-led delivery had lower fidelity (80%) and discipline issues during substance-related sessions. | Teacher-led IPSY: Later initiation and lower increase in alcohol use; reduced expectations of regular smoking; higher resistance to cigarette offers. Peer-led IPSY: Ineffective for alcohol and smoking outcomes; in some cases increased alcohol consumption and lowered resistance to cigarette offers. Both groups showed the normative increase in substance use with age, but only the teacher-led condition showed positive intervention effects. | Student satisfaction was notably higher in the peer-led interventions, with students rating the sessions 4.72/5 versus 4.04/5 in the teacher-led group (p < 0.01), and 100% wanted it offered again (vs. 88% in teacher-led). This shows that peers were perceived as more relatable and engaging, even though their sessions were less effective. The paper suggests that peers’ popularity and social closeness made them appealing facilitators but potentially undermined prevention goals, as all peer leaders drank alcohol and most had tried smoking. The authors recommend that peers be used for non–substance-related life skills sessions, while teachers lead the prevention-specific content. Facilitator credibility and attitudes toward substance use were highlighted as key moderators of program success. |

| Examining the Differential Effectiveness of a Life Skills Program (IPSY) on Alcohol Use Trajectories in Early Adolescence | Michael Spaeth, Karina Weichold, Rainer K. Silbereisen, Margit Wiesner [12]. | IPSY | Germany | Alcohol and Tobacco | 1484 students (47% male, 53% female) | Mean age at baseline = 10.5 years (Grade 5), with follow-up through Grade 7 (approximately age 13) | IPSY was implemented by trained teachers across 23 schools in Thuringia, Germany. Schools were randomly assigned to either the IPSY intervention or a control condition. The program ran for three years: 15 sessions in Grade 5, followed by 7 booster sessions in Grades 6 and 7. Teachers received annual one-day trainings before each implementation phase. Fidelity checks showed that teachers delivered around 80% of the planned material and achieved lesson goals in most sessions, suggesting good implementation quality. The program was embedded into normal school hours and applied in both urban and rural settings. | Researchers measured students’ alcohol use at three time points across Grades 5 to 7, recording both whether they drank and how much they drank. They used growth mixture modelling (GMM), a statistical method that groups individuals based on similar patterns of change over time. This analysis showed that not all adolescents followed the same developmental path in their alcohol use. Two main trajectories were identified. The first was a normative group, which included about 80 percent of students who either did not drink or showed a slow, typical increase in occasional drinking as they got older. The second was a problematic group, which made up about 20 per cent of students who began drinking earlier and showed a much steeper increase in both frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption. Compared with students in control schools, those who participated in IPSY were less likely to belong to the problematic group. Within the normative group, IPSY participants also showed a slower increase in alcohol use over time, meaning that the program helped delay and reduce drinking among the majority of students. These effects were described as small to medium in size, indicating a meaningful though moderate impact. However, IPSY did not significantly reduce drinking among students in the problematic trajectory. Those who were already drinking early or heavily continued on a high-risk path despite participation in the program. Overall, the findings suggest that IPSY was effective for general prevention but less suitable for adolescents who had already initiated alcohol use. | IPSY worked best for the majority of students following a typical developmental path, helping to slow the rise in alcohol use and keep consumption at lower levels. However, it was not effective for adolescents already showing risky behaviour at the start—suggesting that universal programs like IPSY need to be complemented by more focused interventions for high-risk youth. The study also showed that teacher training and fidelity were key to its success: consistent implementation in regular classes helped achieve stable outcomes. |

| Effectiveness of a selective intervention program targeting personality risk factors for alcohol misuse among young adolescents: Results of a cluster randomized controlled trial | Lammers, Jeroen;Goossens, Ferry;Conrod, Patricia;Engels, Rutger;Wiers, Reinout W.;Kleinjan, Marloes [18]. | Preventure | Netherlands | Alcohol | 699 (gender not specified) | 13–15 years old | not reported | The outcome depends on the analysis strategy used: Logistic regression: no significant effects on binge drinking, alcohol use and problem drinking, or alcohol and binge-drinking frequency at 1-year post-intervention (snapshot). Latent growth: over the 12 months after the intervention, there’s significantly less growth in binge drinking and binge drinking frequency (delay). Use assessment: Alcohol Problem: based on RAPI, how often one has experienced each of 18 alcohol-related problems Alcohol use: binomial variable 0=none, 1 or more = 1 (in the past four weeks) Binge drinking: how many times one has had 5 or more drinks on one occasion during the past four weeks (binomial variable) Binge drinking frequency: same as binge drinking Alcohol use frequency: how often one has drunk in the past four weeks (ranging from 0 to 40) | LGC provides a more nuanced and useful perspective for understanding the effect of the intervention over time. |

| Effectiveness of a selective intervention program targeting personality risk factors: Results of interaction analyses | Lammers, Jeroen;Goossens, Ferry;Conrod, Patricia;Engels, Rutger;Wiers, Reinout W.;Kleinjan, Marloes [19]. | Preventure | Netherlands | Alcohol | 699 (gender not specified) No significant moderation effect was found for gender. | 13–15 years old | not reported | The aim of the study was to analyse if certain theory-based subgroups benefit more from the programme than others. Young people having high sensation-seeking benefit from it when we talk about binge drinking and binge drinking frequency with a post hoc latent growth analysis. The ones having high anxiety sensitivity benefit from it when we look at the outcome of alcohol use 12 months post-intervention. No significant effect has been found for the personality traits negative thinking and impulsivity. No significant effect was found for the problem drinking measure. Regression analyses have been made for the primary analysis, and then latent growth has been made as post hoc analyses. Use assessment: Alcohol Problem: based on RAPI, how often one has experienced each of 18 alcohol-related problems Alcohol use: binomial variable 0=none, 1 or more = 1 (in the past four weeks) Binge drinking: how many times one has had 5 or more drinks on one occasion during the past four weeks (binomial variable) Binge drinking frequency: same as binge drinking Alcohol use frequency: how often one has drunk in the past four weeks (ranging from 0 to 40). | Selective prevention program, such as Preventure, seem to be more effective in modifying alcohol misuse behaviour among high-risk adolescents. |

| Effectiveness of a brief school-based intervention on depression, anxiety, hyperactivity, and delinquency: A cluster randomized controlled trial | Goossens, Ferry X.;Lammers, J.;Onrust, S. A.;Conrod, P. J.;de Castro, B. Orobio;Monshouwer, K. [20]. | Preventure | Netherlands | Mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, hyperactivity, and delinquency | 699 students; 48.5% female | Mean age = 14 years | not reported | The findings showed no significant overall effects of the intervention on these outcomes for the total high-risk sample. However, a significant positive effect was observed on anxiety reduction within the anxiety sensitivity (AS) personality group at 12 months post-intervention, while a negative effect on depression was noted in the negative thinking (NT) group. | |

| “Unplugged”: A school-based randomized control trial to prevent and reduce adolescent substance use in the Czech Republic | Gabrhelik, Roman;Duncan, Alexandra;Miovsky, Michal;Furr-Holden, C. Debra M.;Stastna, Lenka;Jurystova, Lucie [27]. | Unplugged | Czech Republic | Alcohol, tobacco, drugs (cannabis) | 1753 students; almost all male | Students in the 6th grade, mean age 11–13 y.o. | changed lesson order, graphics, shortened lessons, and included ice-breaker activities | This program effectively reduced smoking, heavy smoking, and cannabis use among primary school students in the Czech Republic, with statistically significant effects observed for these behaviours at the final follow-up. However, no significant intervention effects were found for alcohol use, frequent drunkenness, or lifetime drug use. The program demonstrated promising outcomes for tobacco and marijuana prevention, highlighting its potential as a universal prevention strategy for adolescent substance use in school settings. | |

| Effects of a School-Based Prevention Program on European Adolescents’ Patterns of Alcohol Use | Maria Paola Caria, Fabrizio Faggiano, Rino Bellocco, Maria Rosaria Galanti, [23]. | Unplugged | 7 European countries (Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Alcohol (program also covers tobacco and illict drugs but study only reports on alcohol) | 7079 students (49% of those that completed the follow-up were female) | 12–14 years old | 3-day interactive training course for teachers used to standardise implementation across countries. | Participation did not modify the risk of being a current drinker but did significantly lower self-reported alcohol-related behavioural problems by an estimated 22% (absolute risk reduction = 1.9%) among students who did not drink at baseline and those who perceived their parents to tolerate drinking; non-drinkers at baseline were more likely to remain non-drinkers and less likely to start drinking frequently, and occasional drinkers were less likely to become frequent drinkers. | Greater impact on alcohol-related problems than use frequency but did appear to slow the transitions between stages of drinking (nondrinkers more likely to remain nondrinkers, occasional drinkers show slower progression towards frequent drinking); Stronger effect on alcohol-related problem behaviours among boys. |

| The effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: EU-Dap cluster randomised controlled trial | Fabrizio Faggiano, Maria Rosaria Galanti, Karl Bohrn, Gregor Burkhart, Federica Vigna-Taglianti, Luca Cuomo, Leila Fabiani, Massimiliano Panella, Tatiana Perez, Roberta Siliquini, Peer van der Kreeft, Maro Vassara, Gudrun Wiborg, [24]. | Unplugged | 7 European countries (Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Alcohol, tobacco, drugs (cannabis) | 7079 students (1497 female) | 12–14 years old | 3-day interactive training course for teachers used to standardise implementation across countries | Short-term exposure to the programme is linked to an estimated 30% effect on the use of cigarettes, cannabis, and alcohol (among the most effective school-based programmes), with significantly lower prevalence of daily cigarette use, episodes of drunkenness, and cannabis use in a 30-day window; it delays daily smoking rather than reducing frequent use. | Intervention arms that included parents or peer leaders did not appear more effective than the basic model; results could not be compared across countries due to statistical power and the short window of follow-up (under 4 months). |

| The effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: 18-Month follow-up of the EU-Dap cluster randomized controlled trial | Fabrizio Faggiano, Federica Vigna-Taglianti, Gregor Burkhart, Karl Bohrn, Luca Cuomo, Dario Gregori, Massimiliano Panella, Maria Scatigna, Roberta Siliquini, Laura Varona, Peer van der Kreeft, Maro Vassara, Gudrun Wiborg, Maria Rosaria Galanti, [25]. | Unplugged | 7 European countries (Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Alcohol, tobacco, drugs (cannabis) | 7079 (47.8% of those who completed the 18-month follow-up were female) | 12–14 years old | 3-day interactive training course for teachers used to standardise implementation across countries | 15 months post-exposure, we see significantly lower prevalence of cannabis use (26% estimated reduction) and episodes of drunkenness (38% estimated reduction) but no significant reduction in tobacco use despite preventing progression towards initial use. | The second follow-up to the study above showed similar results for cannabis and alcohol use but not for tobacco use, with similar issues with intervention arms. |

References

- Colomer-Pérez, N.; Chover-Sierra, E.; Navarro-Martínez, R.; Andriusevičienė, V.; Vlachou, E.; Cauli, O. Alcohol and Drug Use in European University Health Science Students: Relationship with Self-Care Ability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, K.E.; Newton, N.C.; Barrett, E.L.; Teesson, M. A systematic review of school-based alcohol and other drug prevention programs facilitated by computers or the Internet. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012, 32, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallari, E.; Soukup, T.; Kyriacou, A.; Lewison, G. Assessing the European impact of alcohol misuse and illicit drug dependence research: Clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based policy. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2020, 23, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggiano, F.; Minozzi, S.; Versino, E.; Buscemi, D. Universal school-based prevention for illicit drug use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2024, CD003020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edalati, H.; Conrod, P.J. A Review of Personality-Targeted Interventions for Prevention of Substance Misuse and Related Harm in Community Samples of Adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrod, P.J. Personality-Targeted Interventions for Substance Use and Misuse. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2016, 3, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigna-Taglianti, F.D.; Galanti, M.R.; Burkhart, G.; Caria, M.P.; Vadrucci, S.; Faggiano, F. “Unplugged,” a European school-based program for substance use prevention among adolescents: Overview of results from the EU-Dap trial. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2014, 2014, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichold, K.; Blumenthal, A. Long-Term Effects of the Life Skills Program IPSY on Substance Use: Results of a 4.5-Year Longitudinal Study. Prev. Sci. 2015, 17, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichold, K. Translation of etiology into evidence-based prevention: The life skills program IPSY. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2014, 2014, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, V.; Weichold, K.; Silbereisen, R.K. The life skills program IPSY: Positive influences on school bonding and prevention of substance misuse. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichold, K.; Silbereisen, R.K. Peers and Teachers as Facilitators of the Life Skills Program IPSY: Results from a Pilot study. Sucht 2012, 58, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaeth, M.; Weichold, K.; Silbereisen, R.K.; Wiesner, M. Examining the differential effectiveness of a life skills program (IPSY) on alcohol use trajectories in early adolescence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, N.C.; Champion, K.E.; Slade, T.; Chapman, C.; Stapinski, L.; Koning, I.; Tonks, Z.; Teesson, M. A systematic review of combined student- and parent-based programs to prevent alcohol and other drug use among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017, 36, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRISMA. Scoping [Internet].PRISMA Statement. 2018. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/scoping (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Conrod, P.J.; O’Leary-Barrett, M.; Newton, N.; Topper, L.; Castellanos-Ryan, N.; Mackie, C.; Girard, A. Effectiveness of a Selective, Personality-Targeted Prevention Program for Adolescent Alcohol Use and Misuse. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edalati, H.; Afzali, M.H.; Castellanos-Ryan, N.; Conrod, P.J. The Effect of Contextual Risk Factors on the Effectiveness of Brief Personality-Targeted Interventions for Adolescent Alcohol Use and Misuse: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 43, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier-Ménard, E.; Castellanos-Ryan, N.; O’Leary-Barrett, M.; Girard, A.; Conrod, P.J. The impact of youth internalising and externalising symptom severity on the effectiveness of brief personality-targeted interventions for substance misuse: A cluster randomised trial. Addict. Behav. 2017, 75, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, J.; Goossens, F.; Conrod, P.; Engels, R.; Wiers, R.W.; Kleinjan, M. Effectiveness of a selective intervention program targeting personality risk factors for alcohol misuse among young adolescents: Results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2015, 110, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers, J.; Goossens, F.; Conrod, P.; Engels, R.; Wiers, R.W.; Kleinjan, M. Effectiveness of a selective alcohol prevention program targeting personality risk factors: Results of interaction analyses. Addict. Behav. 2017, 71, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, F.X.; Lammers, J.; Onrust, S.A.; Conrod, P.J.; de Castro, B.O.; Monshouwer, K. Effectiveness of a brief school-based intervention on depression, anxiety, hyperactivity, and delinquency: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 25, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrinkova, L.; Orosova, O.; Neves De Jesus, S.; Gajdosova, B.; Bacikova-Sleskova, M. Resilience factors, the school-based universal prevention program ‘Unplugged’ and healthy behavior among early adolescents. Eur. J. Ment. Health 2021, 16, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agabio, R.; Trincas, G.; Floris, F.; Mura, G.; Sancassiani, F.; Angermeyer, M.C. A systematic review of school-based alcohol and other drug prevention programs. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2015, 11, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caria, M.P.; Faggiano, F.; Bellocco, R.; Galanti, M.R.; EU-Dap Study Group. Effects of a school-based prevention program on European adolescents’ patterns of alcohol use. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faggiano, F.; Galanti, M.R.; Bohrn, K.; Burkhart, G.; Vigna-Taglianti, F.; Cuomo, L.; Fabiani, L.; Panella, M.; Perez, T.; Siliquini, R.; et al. The effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: EU-Dap cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faggiano, F.; Vigna-Taglianti, F.; Burkhart, G.; Bohrn, K.; Cuomo, L.; Gregori, D.; Panella, M.; Scatigna, M.; Siliquini, R.; Varona, L.; et al. The effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: 18-Month follow-up of the EU-Dap cluster randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010, 108, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrhelik, R.; Duncan, A.; Lee, M.H.; Stastna, L.; Furr-Holden, C.D.M.; Miovsky, M. Sex specific trajectories in cigarette smoking behaviours among students participating in the Unplugged school-based randomized control trial for substance use prevention. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrhelik, R.; Duncan, A.; Miovsky, M.; Furr-Holden, C.D.; Stastna, L.; Jurystova, L. “Unplugged”: A school-based randomized control trial to prevent and reduce adolescent substance use in the Czech Republic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 124, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotta, F.; Vigna-Taglianti, F.; Galanti, M.R.; Scatigna, M.; Faggiano, F. Short-term mediating factors of a school-based intervention to prevent youth substance use in Europe. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina Martinez, J.; Villanueva-Blasco, V.J. Prevention versus pseudo-prevention: A systematic review of school drug prevention and its indexing in best practice portals. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Miovsky, M.; Novak, P.; Stastna, L.; Gabrhelik, R.; Jurystova, L.; Vopravil, J. The effect of the school-based unplugged preventive intervention on tobacco use in the Czech Republic. Adicciones 2012, 24, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, N.C.; Debenham, J.; Slade, T.; Smout, A.; Grummitt, L.; Sunderland, M.; Barrett, E.L.; Champion, K.E.; Chapman, C.; Kelly, E.; et al. Effect of Selective Personality-Targeted Alcohol Use Prevention on 7-Year Alcohol-Related Outcomes Among High-risk Adolescents. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2242544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, Z.M.; Valente, J.Y.; Galvão, P.P.; Gubert, F.A.; Melo, M.H.S.; Caetano, S.C.; Mari, J.J.; Cogo-Moreira, H. A cluster randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of the school-based drug prevention program #Tamojunto2.0. Addiction 2021, 116, 1580–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdelrahman, A.; Bernad, L.; Harris, F.; Rezzonico, E.; Flahault, A.; Hasselgard-Rowe, J. Prevention of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Illicit Drug Use Among Youth: A Scoping Review of European School-Based Programs with Insights on Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101569

Abdelrahman A, Bernad L, Harris F, Rezzonico E, Flahault A, Hasselgard-Rowe J. Prevention of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Illicit Drug Use Among Youth: A Scoping Review of European School-Based Programs with Insights on Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101569

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdelrahman, Ahmed, Luz Bernad, Fiona Harris, Elodie Rezzonico, Antoine Flahault, and Jennifer Hasselgard-Rowe. 2025. "Prevention of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Illicit Drug Use Among Youth: A Scoping Review of European School-Based Programs with Insights on Mental Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101569

APA StyleAbdelrahman, A., Bernad, L., Harris, F., Rezzonico, E., Flahault, A., & Hasselgard-Rowe, J. (2025). Prevention of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Illicit Drug Use Among Youth: A Scoping Review of European School-Based Programs with Insights on Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101569