Using Conversations, Listening and Leadership to Support Staff Wellness: The CALM Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and Participants

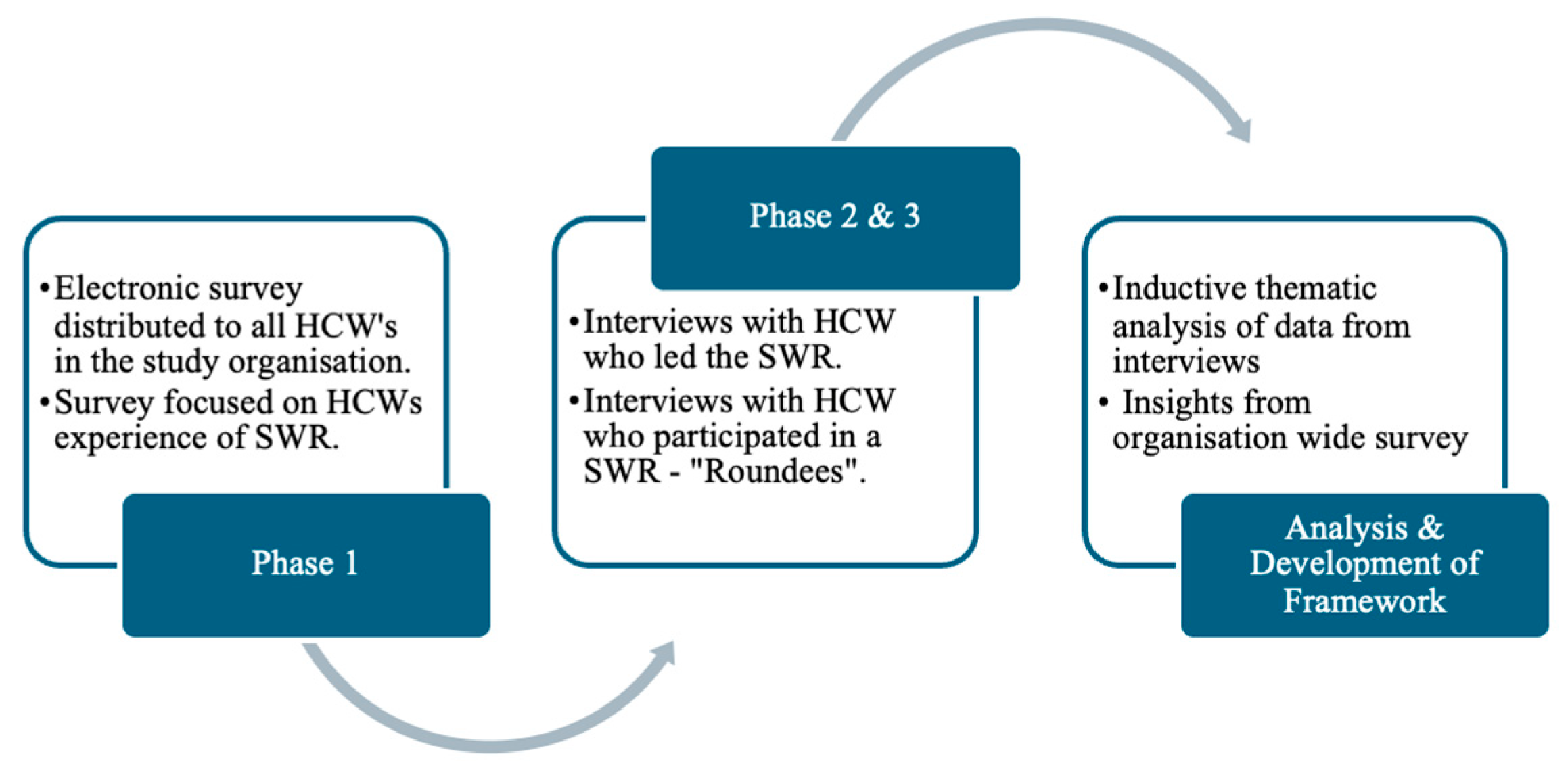

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

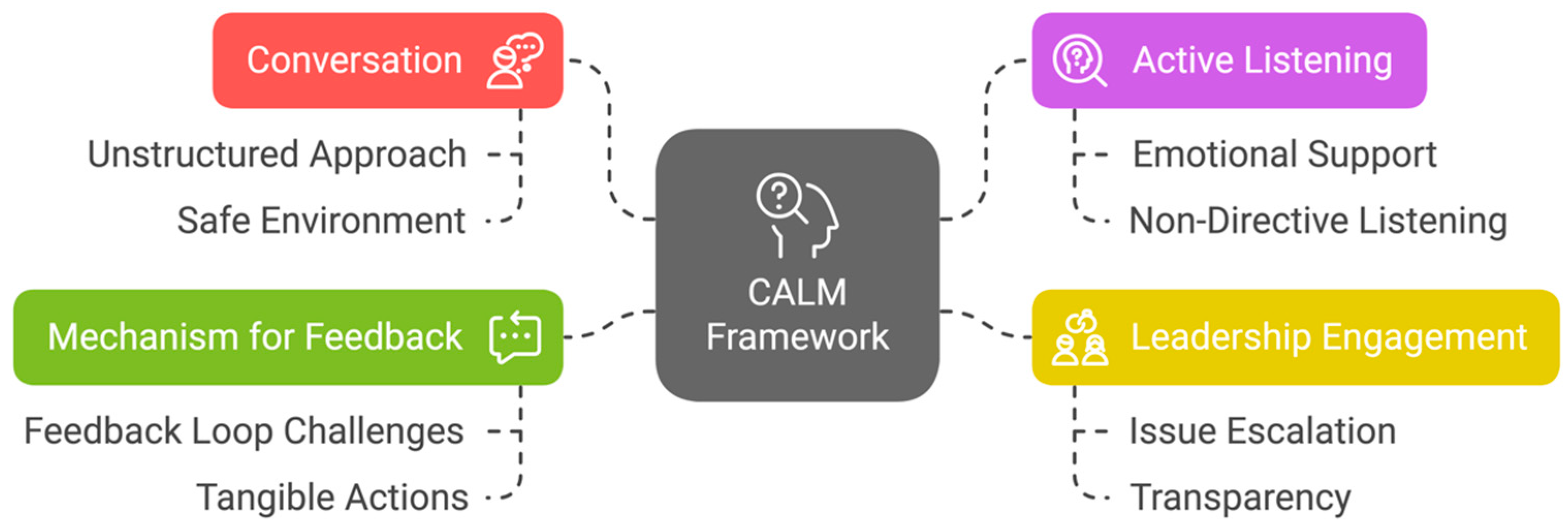

2.5. The Development of the CALM Framework

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Healthcare Organisations

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CALM | Conversation, Active Listening, Leadership Engagement, Mechanism for Feed-back |

| SWR | Staff Wellness Rounding |

| HCWs | Healthcare workers |

References

- Holton, S.; Wynter, K.; Trueman, M.; Bruce, S.; Sweeney, S.; Crowe, S.; Dabscheck, A.; Eleftheriou, P.; Booth, S.; Hitch, D.; et al. Psychological well-being of Australian hospital clinical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust. Health Rev. 2020, 45, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare worker wellness: A scoping review. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, C.; Pignata, S.; Bezak, E.; Tie, M.; Childs, J. Workplace interventions to improve well-being and reduce burnout for nurses, physicians and allied healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Cervoni, C.; Lochner, M.; Marangio, J.; Stanley, C.; Marriott, S. Supporting health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health support initiatives and lessons learned from an academic medical center. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbiks, J.M.; Best, L.A.; Law, M.A.; Roach, S.P. Evaluating the mental health and well-being of Canadian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2021, 34, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albott, C.S.; Wozniak, J.R.; McGlinch, B.P.; Wall, M.H.; Gold, B.S.; Vinogradov, S. Battle buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brower, K.J.; Brazeau, C.M.; Kiely, S.C.; Lawrence, E.C.; Farley, H.; Berliner, J.I.; Bird, S.B.; Ripp, J.; Shanafelt, T. The evolving role of the chief wellness officer in the management of crises by health care systems: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2021, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, M.J.; Chewning, B.; Musuuza, J.; Rees, S.; Green, C.; Patterson, E.; Safdar, N. Leadership rounds to reduce health care–associated infections. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaecht, K.; Seys, D.; Bruyneel, L.; Cox, B.; Kaesemans, G.; Cloet, M.; Broeck, K.V.D.; Cools, O.; De Witte, A.; Lowet, K.; et al. COVID-19 is having a destructive impact on health-care workers’ mental well-being. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2021, 33, mzaa158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Wellness Institute. The Global Wellness Institute. What Is Wellness? 2022. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/what-is-wellness/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Pai, P.; Olcoń, K.; Allan, J.; Knezevic, A.; Mackay, M.; Keevers, L.; Fox, M.; Hadley, A.M. The SEED Wellness Model: A workplace approach to address wellbeing needs of healthcare staff during crisis and beyond. Front. Health Serv. 2022, 2, 844305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.; Smith, L.; Taylor, R.; Kohler, F. Examining the experience of healthcare workers who led staff wellness rounding during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust. Health Rev. 2024, 49, AH24015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenstrom, M.; Harrilson, A.; Heath, M.; Dyess, S. “What’s Old Is New Again”: Innovative Health Care Leader Rounding—A Strategy to Foster Connection. Nurse Lead. 2022, 20, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins-Browne, K.; Lewis, M.; Burchill, L.J.; Gilbert, C.; Johnson, C.; O’DOnnell, M.; Kotevski, A.; Poonian, J.; Palmer, V.J. Interventions to support the mental health and well-being of front-line healthcare workers in hospitals during pandemics: An evidence review and synthesis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e061317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiss, D.; Confino, M.L.-R.; Wei, E.; Reyes, M.; Coll, J.P.; Rodriguez, T.P.; Foster-Mahfuz, A.; Foote, B.A.B.; Segall, J.L.; Mastromano, C.M.; et al. Answering the call to action: A multimodal wellness response to psychological distress in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Bronx. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2022, 37, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, R.A.; Nashwan, A.J.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Abdalla, A.Q.; Ameen, B.M.M.; Khdhir, R.M. Using thematic analysis in qualitative research. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2025, 6, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontalay, A.; Suksatan, W.; Prabsangob, K.; Sadang, J.M. Healthcare workers’ burdens during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative systematic review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 2021, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.; Peirce, J.; Van Wert, M.; Wood, C.; Burhanullah, H.; Swartz, K. Psychological first aid well-being support rounds for frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 669009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, A.B.; Wank, A.A.; Vanuk, J.R.; O’cOnnor, M.-F.; Dreifuss, B.A.; Dreifuss, H.M.; Ellingson, K.D.; Khan, S.M.; Friedman, S.E.; Athey, A. Implementing psychological first aid for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A feasibility study of the ICARE model. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2023, 30, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, H.; Gupta, A.; Javed, M.; Wood, B.; Knowles, S.; Coyne, E.; Cooper, J. COVID-well study: Qualitative evaluation of supported wellbeing centres and psychological first aid for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuber, F.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Rieger, M.A.; Gündel, H.; Ruhle, S.; Zipfel, S.; Junne, F. The effectiveness of health-oriented leadership interventions for the improvement of mental health of employees in the health care sector: A systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabin, L.M.; Abu Zaitoun, R.S.; Sweity, E.M.; de Tantillo, L. The relationship between job stress and patient safety culture among nurses: A systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, C.; Sommerfield, A.; von Ungern-Sternberg, B.S. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfik, D.S.; Scheid, A.; Profit, J.; Shanafelt, T.; Trockel, M.; Adair, K.C.; Sexton, J.B.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Evidence relating health care provider burnout and quality of care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, U.I.; Qureshi, A.; Lal, K.; Ali, S.; Barkatali, A.; Nayani, S. Implementation and evaluation of Employee Health and Wellness Program using RE-AIM framework. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2022, 15, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machen, R.; Cuddihy, T.F.; Reaburn, P.; Higgins, H. Development of a workplace wellness promotion pilot framework: A case study of the blue care staff wellness program. Asia-Pac. J. Health Sport Phys. Educ. 2010, 1, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korman, M.B.; Steinberg, R.; Gagliardi, L.; Stewart, B.; Acero, C.L.; Davies, J.; Maunder, R.; Walker, T.; DasGupta, T.; DiProspero, L.; et al. Implementing the STEADY wellness program to support healthcare workers throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibe, B.; Perticone, K.; Hebert, C. Creating wellness in a pandemic: A practical framework for health systems responding to COVID-19. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2021, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Keyworth, C.; Alzahrani, A.; Pointon, L.; Hinsby, K.; Wainwright, N.; Moores, L.; Bates, J.; Johnson, J. Barriers and enablers to accessing support services offered by staff wellbeing hubs: A qualitative study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1008913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Meyer, I.S. Applying empathic communication skills in clinical practice: Medical students’ experiences. South Afr. Fam. Pract. 2021, 63, 5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; A Wong, C.; Cummings, G.G.; Grau, A.L. Resonant leadership and workplace empowerment: The value of positive organizational cultures in reducing workplace incivility. Nurs. Econ. 2014, 32, 5–15, 44; quiz 16. [Google Scholar]

| CALM Framework Component | Findings from Staff Survey (Phase One) | Findings from Leader Rounder Interviews (Phase Two) | Findings from Roundee Interviews (Phase Three) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conversation | 74% valued informal, open conversations. 85.2% liked positive reinforcement. | Leader Rounders required skills that support staff to have open conversations | Roundees appreciated the relaxed, non-judgmental atmosphere. | Informal conversations foster trust and openness, building connection. |

| Active Listening | 74% felt heard, and desired compassionate listening rather than immediate solutions. | Leader rounders required active listening skills, and the ability to provide emotional support | Roundees valued active listening and emotional support. | Active listening and emotional support are essential, with a preference for listening over problem-solving. |

| Leadership Engagement | 77.5% felt wellness rounds allowed them to escalate issues to management. | Leaders acted as communicators and facilitators of staff feedback | Leaders acted as communicators and facilitators for staff feedback. | Leadership plays a pivotal role in feedback escalation, addressing concerns, and supporting staff. |

| Mechanism for Feedback | 77.5% felt they could escalate issues, but only 32.5% felt feedback was adequately addressed. | Leader rounders required a process and the skills to theme feedback and to escalate issues to senior executive | Roundees wanted more visible actions on their feedback. | A gap exists between feedback collection and tangible change, indicating a need for greater transparency and accountability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iqbal, U.; Wilson, N.; Taylor, R.; Smith, L.; Kohler, F. Using Conversations, Listening and Leadership to Support Staff Wellness: The CALM Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101558

Iqbal U, Wilson N, Taylor R, Smith L, Kohler F. Using Conversations, Listening and Leadership to Support Staff Wellness: The CALM Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101558

Chicago/Turabian StyleIqbal, Usman, Natalie Wilson, Robyn Taylor, Louise Smith, and Friedbert Kohler. 2025. "Using Conversations, Listening and Leadership to Support Staff Wellness: The CALM Framework" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101558

APA StyleIqbal, U., Wilson, N., Taylor, R., Smith, L., & Kohler, F. (2025). Using Conversations, Listening and Leadership to Support Staff Wellness: The CALM Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101558