1. Introduction

Climate change has increased the frequency and severity of extreme weather that threatens public health [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Extreme weather events such as hurricanes and tornados place adults ages 65 and older at increased risk of mortality due to chronic health conditions and limitations in mobility [

6]. Some reviews have argued that disastrous weather also disproportionately disadvantages older adults’ mental health [

7,

8,

9], but others have suggested that older age is protective [

10]. A meta-analysis of six studies found that older age increased the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adjustment disorder following earthquakes and tsunamis, but was unrelated to depression and anxiety [

11]. Other research found that older age was associated with fewer symptoms of depression and PTSD after hurricanes and floods [

12,

13,

14,

15].

In the current study, we drew from two prominent theories of aging and emotional well-being, socioemotional selectivity theory (SST) [

16], and the strength and vulnerability integration model (SAVI) [

17], to investigate potential age differences in the impact of extreme weather or natural disaster and associated adversities on depression and anxiety. The two theories offer contrasting predictions about age differences in emotional resilience. As such, they are well-suited to offer new insights regarding age differences in emotional well-being following climate events. In our investigation, we used data from a national U.S. sample of adults who had or had not experienced a severe storm, tornado, flood, or another extreme weather event or natural disaster in the past month. Much of what is currently known about aging and post-disaster well-being is based on hurricanes [

12], floods [

14], and earthquakes [

18]. By considering a broader array of events, we aimed to expand knowledge to climate events that are increasing with global warming such as storms, droughts, floods, and heatwaves [

19].

Aside from inconclusive findings for age differences in post-disaster well-being, cross-sectional and longitudinal research has found that positive emotions increase and negative emotions decrease with age [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Researchers have labeled this the “well-being paradox” to capture the unexpected nature of age-related improvements occurring alongside decreased physical functioning and other losses [

25]. Epidemiological studies found that mood and anxiety disorders were less prevalent in U.S. adults 65 and older compared to middle-aged adults [

26,

27]. This was also apparent in Western, industrialized countries during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. However, not all evidence has been consistent. In the U.S., men aged 70 and older have the highest suicide rate [

8,

34] and a meta-analysis based on data from several countries indicated that the likelihood of depression increased from age 55 to 89 [

35].

Socioemotional selectivity theory (SST) posits that benefits of aging for emotional well-being stem from an increasing awareness that future time left in life is limited which shifts motivation away from the future-oriented goals commonly pursued earlier in life towards pursuing emotional meaning in the “here and now” [

16]. Around 60 years of age, perceptions of a limited future overshadowed views of future opportunities [

36]. In line with SST, when future time perspective was experimentally limited, individuals prioritized their emotional well-being by, for example, attending more to positive than negative information, choosing to spend time with loved ones, and capitalizing on appealing opportunities [

37,

38,

39].

SST predicts robust benefits of aging for emotional well-being so long as motivation to pursue emotional meaning remains intact [

16]. The COVID-19 pandemic was more disruptive to younger adults’ goals than to goals pursued by older adults [

40], and this may explain why older adults experienced less psychological distress [

31]. Sociocultural events that threatened mortality, including the SARS epidemic and the September 11 attacks, heightened the pursuit of emotional meaning among adults of all ages [

41]. Similarly, extreme weather may threaten mortality and bolster older adults’ motivation to seek emotional meaning while disrupting younger adults’ future-oriented goals. Indeed, at least one study found a stronger association between older age and reporting fewer depression symptoms after a hurricane for those who had an associated adversity versus those who had not [

15]. Because few studies have considered that exposure to adversity may moderate age differences in post-disaster emotional well-being, the generalizability of this finding is unknown.

The SAVI model argues that age-related emotional benefits stem mainly from avoidance of known stressors [

17]. Sustained unavoidable stressors are thought to temporarily diminish age-related advantages for emotional well-being due to physiological vulnerabilities that impair downregulation of negative arousal. Accordingly, during periods of acute stress, between-person age differences in emotional well-being that favor older adults are expected to attenuate or disappear while within-person decreases in emotional well-being are expected to be more pronounced at older ages [

42]. In line with SAVI, older age was associated with less negative affect when an interpersonal stressor was avoided, but not when a stressor was encountered [

43]. Pandemic stressors increased negative affect for both older and younger adults [

44].

Consistent with SAVI, research found worse emotional well-being in older adults after sudden-onset disasters like earthquakes [

11], although not all evidence has been consistent [

18]. Research inconsistent with SAVI was based mostly on hurricanes in the U.S. Gulf Coast, a region accustomed to dealing with seasonal hurricanes [

12,

15]. Prior stressful experiences can inoculate against distress when similar challenges re-occur [

45]. Older adults on the Gulf Coast may have drawn upon their life experience with hurricanes to cope [

46]. It remains unclear if older age is associated with emotional resilience in regions less prone to extreme weather. Climate change may introduce new stressors for such individuals [

47].

Psychological distress has been found to spike after a traumatic event and then abate [

48]. Most research on age differences has investigated emotional well-being several months, or even years, post-disaster [

11]. The heightened vulnerability of older adults to unavoidable stressors predicted by SAVI may be more evident when emotional well-being is assessed sooner after the stressful event [

42].

Sociodemographic characteristics related to age, including poorer perceived health [

49], increase the risk of emotional distress after a disaster [

15,

50]. Furthermore, older adults describe chronic health problems as a factor that increases their vulnerability to climate stressors [

47]. Taking perceived health into account may thus facilitate a better understanding of the association between extreme weather events and age differences in emotional well-being.

In our study, we used self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety as indicators of emotional well-being. Experiencing less negative mood is one component of subjective well-being, also referred to as hedonic well-being [

51,

52]. Our research question asked: After extreme weather or natural disasters, are there age-related differences in depression and anxiety that depend on exposure to related adversity, after accounting for perceived health? Drawing from SST [

16], we hypothesized that older age would be associated with fewer depression (Hypothesis 1a) and anxiety (Hypothesis 1b) symptoms. Drawing from SAVI [

17], we hypothesized that among those who had experienced weather- or disaster-related adversity, the association between older age and fewer depression (Hypothesis 2a) and anxiety (Hypothesis 2b) symptoms would be weaker. Drawing from research on age differences in post-disaster emotional well-being [

15], we considered the alternative hypothesis that among those who had experienced weather- or disaster-related adversity, the association between older age and fewer depression (Hypothesis 3a) and anxiety symptoms (Hypothesis 3b) would be stronger.

4. Discussion

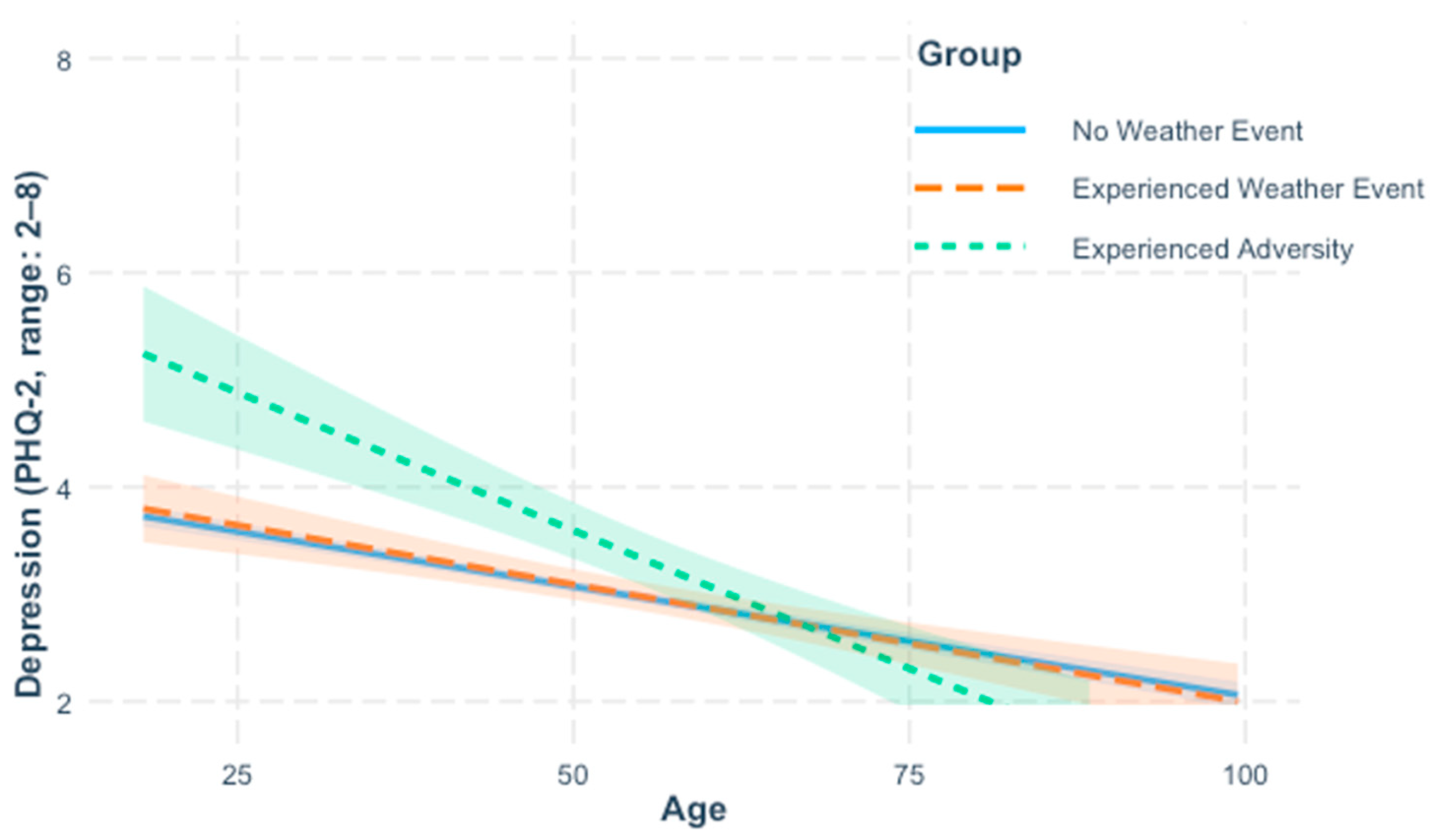

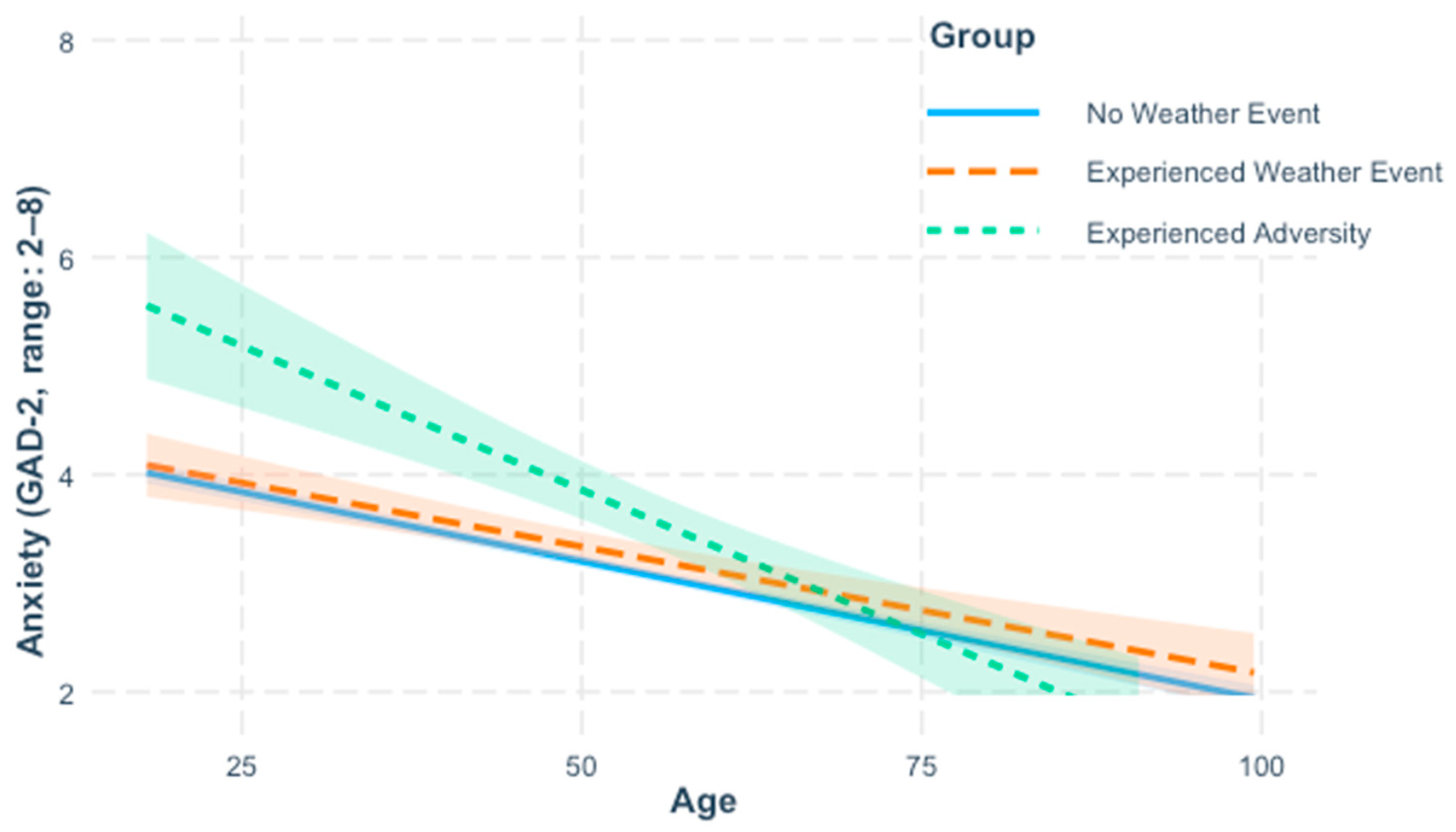

We used data from a national U.S. sample of adults who had or had not experienced extreme weather or natural disaster to test theory-driven hypotheses about age differences in emotional resilience in the face of climate change. SST points to age-related motivational shifts to predict robust advantages of aging for emotional well-being [

16]. SAVI predicts that sustained unavoidable stressors will attenuate age-related benefits [

17]. Consistent with SST, we found that older age was associated with reporting fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety. In contrast to SAVI, these benefits of aging were not weaker among individuals who had experienced adversity due to extreme weather or natural disaster. Instead, age-related reductions in reported symptoms of anxiety and depression were even stronger among individuals who had experienced weather- or disaster-related adversity, confirming predictions based on prior research [

15].

The extreme weather events or natural disasters and adversities reported by individuals in our study were diverse, with severe storms being the most common event and property loss the most common adversity. Individuals who experienced adversities as a consequence of extreme weather or natural disaster reported more depression and anxiety symptoms, highlighting the mental health costs of extreme weather, and by extension climate change. Prior research showed similar negative impacts for mental health following hurricane-related adversities [

13,

15]. The generalizability of these findings to the diverse events reported in our study suggest that the increasing prevalence of extreme weather with climate change [

5,

19] may further worsen already increasing rates of depression and anxiety in the U.S. [

62].

Older age was associated with reporting fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety, echoing findings from a large body of research on aging and emotional well-being [

23]. Our findings highlight the robustness of these benefits, with stronger age-related reductions in anxiety and depression in the adversity group compared to the weather and non-event groups. SST attributes well-being benefits of aging to life-span increases in motivation to pursue emotional meaning [

16]. Facing adversities due to extreme weather or natural disaster may bolster a focus on emotional meaning, consistent with past findings that mortality-threatening events—such as the SARS epidemic and the September 11 attacks—heightened pursuit of emotionally meaningful goals across adulthood [

41]. As during the COVID-19 pandemic [

40], facing weather-related adversities may have disrupted younger adults’ pursuit of future-oriented goals, dampening their emotional well-being.

The SAVI model links emotional well-being benefits of aging to stressor avoidance and predicts that unavoidable stressors attenuate age-related advantages for emotional well-being [

17], but this was not evident. SAVI acknowledges that older adults’ greater life experience facilitates their emotional well-being, and life experience may have inoculated older adults against weather- or disaster-related adversity [

14]. SAVI also emphasizes that age-related vulnerabilities are localized to episodes of acute distress [

42]. Our retrospective methods may have contributed to our results since any distress associated with adversity likely faded over time. When reflecting on past events, older adults tend to recall more positive than negative information [

63]. They also ruminate less about negative events [

64,

65] and use positive reappraisal more [

66]. Together, these factors may help to explain why older age was associated with reporting less distress following exposure to weather- or disaster-related adversities.

4.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

Exposure to adversity related to extreme weather or natural disaster was associated with increased symptoms of depression and anxiety, emphasizing the growing need for mental health services in the face of climate change [

3]. Communities can strengthen climate adaptation efforts by integrating psychological services into their plans, for example, by training first responders in psychological first-aid [

67]. Expanding access to greenspace may also buffer the mental health impacts of climate change, while simultaneously promoting appreciation for natural environments and motivating climate action [

68,

69,

70]. Embedding mental health care in primary care, telemedicine, and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy, are ways to expand access to treatment [

71,

72,

73]. Along with expanded access, reducing stigma is key so that those who could benefit from care seek it [

74].

Although older age was associated with reporting fewer anxiety and depression symptoms, natural disasters are known to increase older adults’ mortality risk [

6]. Many older adults recognize that chronic health problems increase their vulnerability to climate-related stressors [

47], but they may underestimate their risk, lack knowledge of how to prepare, and be less likely than younger adults to make emergency plans [

75,

76]. Emergency preparedness communications for older adults may be more effective when they appeal to emotional meaning [

77] and are delivered through preferred formats, such as physical mail rather than email [

76].

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

Like all studies, our study must be understood in light of its limitations. Individuals who experienced severe adversities following extreme weather or natural disaster may have been unable or unwilling to respond to the survey. Those who did respond reported adversities experienced within the past 30 days and depression and anxiety symptoms within the past 14 days. This means that any symptoms that were present but abated before this 14-day window were not captured. Similarly, if adversities occurred prior to the 30-day window but symptoms persisted, this was not represented in our data. As such, our results may underestimate the association between adversities and emotional well-being. In addition, there was considerable heterogeneity in the severity of adversities reported by individuals. Further research is necessary to understand the extent to which event severity moderates our findings. In such investigations, it will be important to account for individual differences in appraisals of adversities which have been shown to vary by age [

78]. Furthermore, our findings based on a U.S. national sample may not generalize to populations outside of the U.S. due to regional differences in vulnerability to climate events, access to healthcare, and cultural differences in strategies for coping with adversity [

79,

80].

One challenge to understanding the consequences of extreme weather or natural disaster is identifying and contacting individuals who have experienced an event. Much research has targeted survivors after a hurricane, flood, or earthquake and measured their well-being several months or even years afterwards [

11]. Our study used a different approach by surveying members of an existing national panel and asking them to report events they had experienced in the last 30 days. Our method lacks efficiency since the vast majority of individuals were not exposed to any extreme weather or natural disaster. However, it facilitates collection of data soon after an event and allows diverse events to be investigated. It also captures individuals’ definitions of extreme weather or natural disaster, which may not necessarily match governmental declarations of emergency or disaster. Understanding how individuals define extreme weather and natural disaster may yield new insights about the impact of climate change on emotional resilience.

The correlational, cross-sectional, retrospective design we used precludes causal conclusions. We cannot rule out the possibility that individuals who were less depressed or anxious prior to experiencing extreme weather or natural disaster were less likely to perceive associated consequences as adversities. In addition, the age differences we found may reflect distinct experiences of different birth cohorts rather than maturational change. To disentangle birth cohort and maturation, future research could employ a cohort-sequential design to follow multiple birth cohorts across time [

81].

Our data were collected in May. There is substantial seasonable variation in extreme weather and heatwaves were not well-represented in our data. Heatwaves may harm mental health even in the absence of associated adversities. Monthly temperatures above 30 °C have been linked to increased reports of mental health problems [

82]. Extreme heat and cold pose significant risks to older adults’ physical health due to deficits in thermoregulation [

83]; further research is necessary to understand risks to mental health. Identifying pathways that link extreme heat to mental health problems and how these pathways vary by age is essential for designing interventions to support climate adaptation.

Our results are based on events occurring within a 30-day interval. Cumulative exposure to weather-related adversities over longer intervals may reveal age-related vulnerabilities posited by SAVI when using longitudinal methods to investigate within-person change instead of the between-person differences we investigated [

42]. More broadly, studying the consequences of multiple events over time could highlight the link between extreme weather and climate change and shift planning away from reactive emergency response toward climate change adaptation [

67].

Although the SAVI model predicts that unavoidable stressors temporarily diminish the emotional well-being advantages of older adults due to age-related physiological vulnerabilities, this process applies specifically to within-person changes during periods of acute stress. Our study, in contrast, examined between-person differences in depression and anxiety symptoms following adversity due to extreme weather or natural disaster. From this perspective, our finding that age-related emotional advantages were strongest among those who experienced adversity appears inconsistent with SAVI’s general implication that older adults are more emotionally vulnerable under stress. It does not, however, directly test SAVI’s within-person prediction that emotional well-being is compromised in the moment of high arousal. Further work using longitudinal or experience sampling methods would be needed to assess this key prediction.