Knowledge and Practices on Household Disposal of Unused Antimicrobials in Ho Municipality, Ghana

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Study Population and Sample Size

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Quality Control

2.6. Data Handling and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demography of Respondents

3.2. Knowledge and Awareness of Unused Antimicrobials

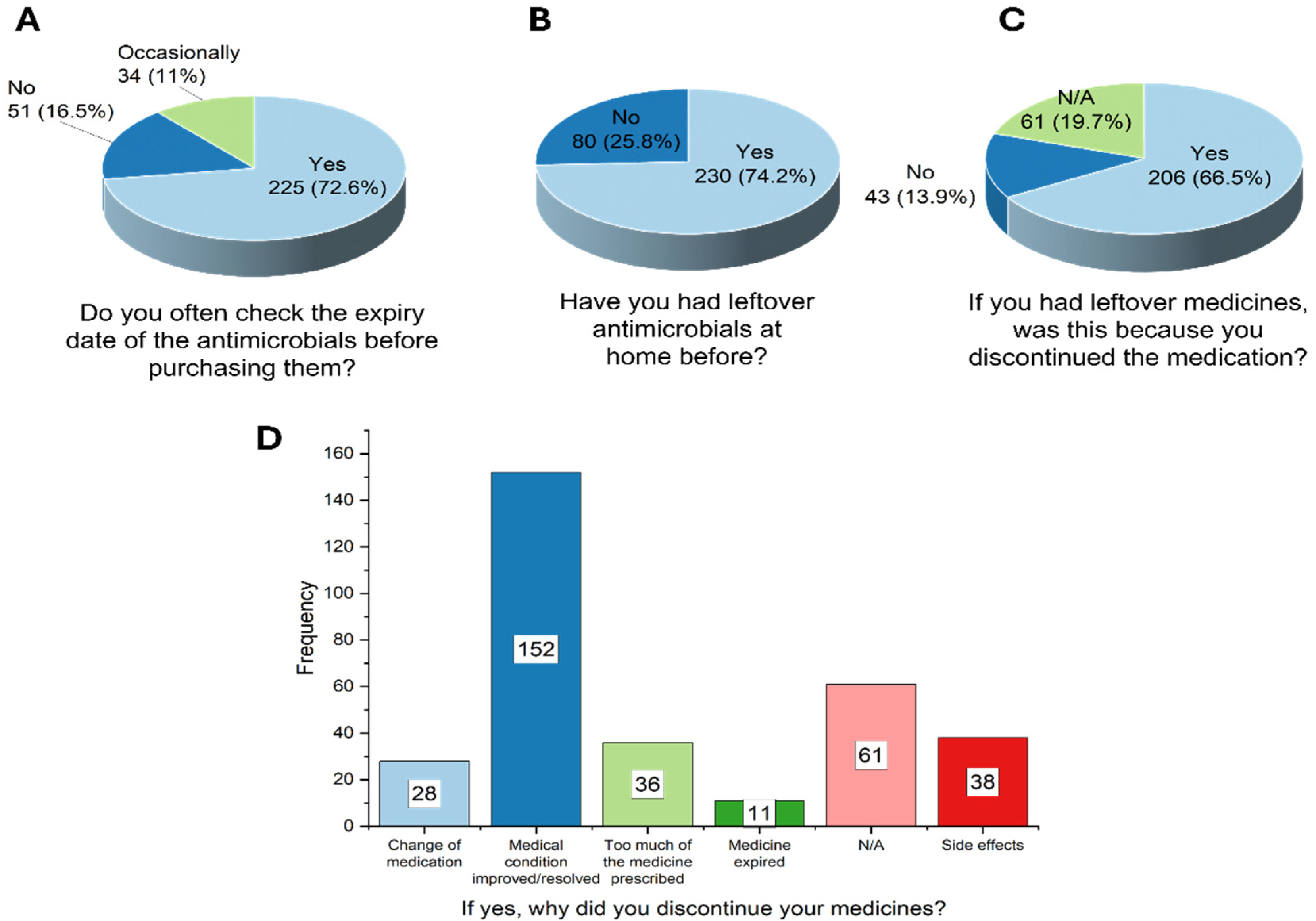

3.3. Respondents’ Practices About Antimicrobial Use and Disposal

3.4. Attitude and Perception of Unused Antimicrobials

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CHPS | Community Health Planning and Services |

| FDA | Food and Drugs Authority |

| NGOs | Non-governmental organizations |

| OTCMS | Over-The-Counter Medicine Sellers |

References

- Anwar, M.; Iqbal, Q.; Saleem, F. Improper disposal of unused antibiotics: An often overlooked driver of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insani, W.N.; Qonita, N.A.; Jannah, S.S.; Nuraliyah, N.M.; Supadmi, W.; Gatera, V.A.; Alfian, S.D.; Abdulah, R. Improper disposal practice of unused and expired pharmaceutical products in Indonesian households. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroop, H.S.; Chakraborty, A.; Virupakshaiah, A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of medical professionals towards the safe disposal of unused medications in South India. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 4, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Seehusen, D.A.; Edwards, J. Patient practices and beliefs concerning disposal of medications. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2006, 19, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, I.T.; Santos, L. Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: A review of the European scenario. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 736–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassmeyer, S.T.; Hinchey, E.K.; Boehme, S.E.; Daughton, C.G.; Ruhoy, I.S.; Conerly, O.; Daniels, R.L.; Lauer, L.; McCarthy, M.; Nettesheim, T.G.; et al. Disposal practices for unwanted residential medications in the United States. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoabeng, I.A.; Otoo, B.A.; Darko, G.; Borquaye, L.S. Disposal of Unused and Expired Medicines within the Sunyani Municipality of Ghana: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Environ. Public Health. 2022, 2022, 6113346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala, G.A.; Bellingham, K.; Vidhamaly, V.; Boupha, P.; Boutsamay, K.; Newton, P.N.; Caillet, C. Substandard and falsified antibiotics: Neglected drivers of antimicrobial resistance? BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, E008587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health-Care Waste; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kümmerer, K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment-A review-Part, I. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bound, J.P.; Voulvoulis, N. Household disposal of pharmaceuticals as a pathway for aquatic contamination in the United Kingdom. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhi, B.; Sewal, R. Ecopharmacovigilance: An issue urgently to be addressed. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2012, 44, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskins, E.; Bickenbach, E.M.; Buchanan, M.; Detter, S.; Ferguson, M.; Freeman, A.; Hoskins, R.; Johnston, A.; Lee, R.; Marks, B.; et al. Quantifying antimicrobial disposals at six community pharmacies with longitudinal medication disposal programs: An underappreciated component of a One Health approach to antimicrobial stewardship. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, ofaf040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmadani, M.A.; Kristina, S.A. A Scoping Review of Disposal of Unused Medicines in Take-Back Programs. J. Manaj. Dan Pelayanan Farm. (J. Manag. Pharm. Pract.) 2021, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Djarbeng, S.N.; Larbi, G.O.; Abdul-Rahman, R.; Osei-Asante, S.; Owusu-Antwi, R. Household acquisition of medicines and disposal of expired and unused medicines at two suburbs in Kumasi-Ghana. Pharma. Innov. 2015, 4, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census. Volume 3A. 2021, pp. 1–128. Available online: http://journal.um-surabaya.ac.id/index.php/JKM/article/view/2203 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Bashaar, M.; Thawani, V.; Hassali, M.A.; Saleem, F. Disposal practices of unused and expired pharmaceuticals among general public in Kabul. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Ayele, Y.; Mamu, M. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards disposal of unused and expired pharmaceuticals among community in Harar city, Eastern Ethiopia. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2018, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairina, E.; Azzahrya, A.B.; Nugraheni, G.; Sulistyarini, A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices for using and disposing of antibiotics: A cross-sectional study at an Indonesian community. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 23, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muflih, S.M.; Al-Azzam, S.; Karasneh, R.A.; Bleidt, B.A.; Conway, B.R.; Bond, S.E.; Aldeyab, M.A. Public knowledge of antibiotics, self-medication, and household disposal practices in Jordan. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2023, 21, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelin, A.d.F.; Bonifácio, N.A.; Nagata, W.B.; da Silva, V.M.S.; Gobbo, L.E.M.; Bresciani, K.D.S. Guidance provided by pharmacists to customers regarding to destination of unused household medications: Disposal of household medications. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paut Kusturica, M.; Jevtic, M.; Ristovski, J.T. Minimizing the environmental impact of unused pharmaceuticals: Review focused on prevention. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1077974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, L.A.A.; Radis-Baptista, G. Pharmaceutical pollution and disposal of expired, unused, and unwanted medicines in the Brazilian context. J. Xenobiotics 2021, 11, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iheanacho, C.O.; Eze, U.I.H. A systematic review of in-patients’ antimicrobial prescriptions and status of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in Nigerian hospitals. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasina, L.; Brucato, A.L.; Falcone, C.; Cucchi, E.; Bresciani, A.; Sottocorno, M.; Taddei, G.C.; Casati, M.; Franchi, C.; Djade, C.D.; et al. Medication Non-Adherence Among Elderly Patients Newly Discharged and Receiving Polypharmacy. Drugs Aging 2014, 31, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori-Asenso, R.; Agyeman, A. Irrational Use of Medicines—A Summary of Key Concepts. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagrou, A.; Chimhutu, V. I Buy Medicines From the Streets Because I Am Poor: A Qualitative Account on why the Informal Market for Medicines Thrive in Ivory Coast. Inquiry 2022, 59, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekoe, S.O.; Ahiabu, M.A.; Orman, E.; Tersbøl, B.P.; Adosraku, R.K.; Hansen, M.; Frimodt-Moller, N.; Styrishave, B. Exposure of consumers to substandard antibiotics from selected authorised and unauthorised medicine sales outlets in Ghana. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2020, 25, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomuyiwa, D.O.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., III; Manirambona, E.; Suleman, M.H.; Rayan, R.A.; Huang, J.; Zaw, T.N.; Babatunde, Y.; Denkyira, S.A.; Musa, S.S. Curbing antimicrobial resistance in post-COVID Africa: Challenges, actions and recommendations. Heal. Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Qurbani, K.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Fareeq, A.; Mahmood, K.A.; Mohamed, M.G. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyari, S.; Senapati, T.K.A.; Kar, A.; Kanyari, S.S.; Kar Sr, A. Disposal Practices of Unused and Expired Medicines Among the General Public and Pharmacies: A Mixed-Method Study in the Odisha State of Eastern India. Cureus 2024, 16, e52359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.M.P.; Cruvinel, V.R.N.; Meiners, D.; Queiroz, C.A.; Galato, D. Medication disposal: A reflection about possible sanitary and environmental risks. Ambient. Soc. 2017, 20, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essilfie-Essel, G.K.N.; Wiafe, E.; Mensah, K.B.; Korbuvi, J.K.A.; Nyoagbe, J.K.N.; Bangalee, V. Pharmaceutical Waste Disposal Practices in Volta Regional Pharmacies. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2024, 34, e700005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, H.; Chandu, H.N.; Thangaraju, P. Need of hours for drug disposal information with package inserts. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 2168–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Aziz, Z.; Wang, E.S.; Chik, Z. Unused medicine take-back programmes: A systematic review. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2024, 17, 2395535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande-Sholabi, W.; Akinyemi, O.O. Self-medication with over-the-counter drugs among consumers: A cross-sectional survey in a Southwestern State in Nigeria. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande-Sholabi, W.; Olaoye, D.Q.; Adebisi, Y.A. Drug take-back program: Assessment of knowledge, practices, and barriers to safe disposal of unused medication among healthcare students in a Nigerian university. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajj, A.; Domiati, S.; Haddad, C.; Sacre, H.; Akl, M.; Akel, M.; Tawil, S.; Abramian, S.; Zeenny, R.M.; Hodeib, F.; et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding the disposal of expired and unused medications among the Lebanese population. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gender | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 175 | 56.5 |

| Female | 135 | 43.5 |

| Total | 310 | 100.0 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–30 | 196 | 63.2 |

| 31–40 | 72 | 23.2 |

| 41–50 | 30 | 9.7 |

| 51–60 | 7 | 2.3 |

| >60 | 5 | 1.6 |

| Total | 310 | 100.0 |

| Level of Education | ||

| None | 4 | 1.3 |

| Basic/primary | 18 | 5.8 |

| Secondary | 59 | 19.0 |

| Tertiary | 199 | 64.2 |

| Postgraduate | 30 | 9.7 |

| Total | 310 | 100.0 |

| Employment status | ||

| Not employed | 26 | 8.4 |

| Student | 99 | 31.9 |

| Private | 74 | 23.9 |

| Public | 95 | 30.6 |

| Self-employed | 16 | 5.2 |

| Total | 310 | 100.0 |

| Knowledge Statement | Agree N (%) | Disagree N (%) | Not Sure N (%) | Total N (%) | Logistic Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant Demographic Predictors | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |||||

| A. Failing to complete antibiotics can contribute to drug resistance | 268 (86.5%) | 23 (7.4%) | 19 (6.1%) | 310 (100%) | None significant | - | - |

| B. Improper disposal of unused antimicrobials can affect the environment | 270 (87.1%) | 17 (5.5%) | 23 (7.4%) | 310 (100%) | Private employment (borderline) | 0.56 (0.31–1.01) | 0.052 |

| C. Improper disposal of unused antimicrobials can affect health | 259 (83.5%) | 24 (7.7%) | 27 (8.7%) | 310 (100%) | Female sex Higher education Self-employed | 1.53 (1.01–2.32) 1.22 (1.02–1.45) 0.51 (0.26–0.99) | 0.046 0.027 0.049 |

| D. Antimicrobial residues in water bodies can affect aquatic life | 283 (91.3%) | 5 (1.6%) | 22 (7.1%) | 310 (100%) | None significant | - | - |

| E. Unused or leftover antimicrobials present potential risks at home | 266 (85.8%) | 17 (5.5%) | 27 (8.7%) | 310 (100%) | Private employment Self-employed | 0.54 (0.30–0.96) 0.52 (0.27–0.99) | 0.034 0.049 |

| F. Children are the most vulnerable to risks associated with unused antimicrobials | 283 (91.3%) | 13 (4.2%) | 14 (4.5%) | 310 (100%) | Female sex Higher education | 1.62 (1.07–2.45) 1.20 (1.00–1.43) | 0.023 0.049 |

| The Hazardous Effects of Unused Antimicrobials Can Be Minimized or Controlled By | Responses | Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | Significant Demographic Predictors | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Providing proper guidance to the consumer | 283 | 91.30% | None significant | - | - |

| Prescribing adequate quantities for patient compliance | 218 | 70.3% | Higher education | 1.29 (1.03–1.62) | 0.027 |

| Reducing the number of prescribed antimicrobials by the doctor | 138 | 44.5% | Higher education Private employment Student status Self-employed | 1.47 (1.16–1.84) 0.41(0.19–0.88) 0.46 (0.23–0.92) 0.32 (0.14–0.78) | 0.001 0.022 0.026 0.012 |

| Donating or sharing the unused antimicrobials | 27 | 8.7% | Higher education | 0.75 (0.57–0.99) | 0.045 |

| Total (N) | 310 | ||||

| Practice | Frequency | Percent * | Logistic Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant Demographic Predictors | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| How often do you share leftover antimicrobials with people with similar symptoms as yours? | |||||

| Always | 13 | 4.2% | Higher education | 0.62 (0.40–0.98) | 0.040 |

| Sometimes | 87 | 28.1% | |||

| Never | 210 | 67.7% | |||

| Total (N) | 310 | 100.0 | |||

| Have you ever disposed of any antimicrobial drug? | |||||

| Yes | 234 | 75.5% | None significant | - | - |

| No | 76 | 24.5% | |||

| Total (N) | 310 | 100.0 | |||

| Have you ever been advised by a healthcare professional about proper antimicrobial disposal? | |||||

| Yes | 77 | 24.8% | Higher education | 1.35 (1.06–1.70) | 0.014 |

| No | 223 | 71.9% | |||

| Not sure | 10 | 3.2% | |||

| Total (N) | 310 | 100.0 | |||

| In what forms do the leftover antimicrobials usually appear? α | |||||

| Tablets/capsules | 265 | 85.5% | |||

| Ointments/creams | 64 | 20.6% | |||

| Suppositories/vaginal pessaries | 26 | 8.4% | |||

| Syrups/suspensions | 49 | 15.8% | |||

| N/A | 30 | 9.7% | |||

| Total (N) | 310 | ||||

| If yes, what method(s) did you use to dispose of the following dosage forms of antimicrobials? Tablets/Capsules α | |||||

| Burn | 55 | 17.7% | Older age Higher education | 1.32 (1.04–1.68) 0.73 (0.58–0.92) | 0.023 0.008 |

| Return to a health facility (hospital/pharmacy) | 7 | 2.3% | |||

| Flush down the toilet/sink | 16 | 5.2% | |||

| Household trash | 202 | 65.2% | Higher education Self-employed | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) 1.89 (1.05–3.41) | 0.038 0.034 |

| Others: I have not | 3 | 1.0% | |||

| Total (N) | 310 | ||||

| Syrups/Suspensions α | |||||

| Burn | 13 | 4.2% | |||

| Household trash | 109 | 35.2% | Female sex | 1.62 (1.02–2.57) | 0.041 |

| Flush down the toilet/sink | 35 | 11.3% | |||

| Return to health facility (hospital/pharmacy) | 7 | 2.3% | Higher education | 1.85 (1.12–3.06) | 0.016 |

| Others: pour away and put the bottle in the trash | 4 | 1.3% | |||

| Total (N) | 310 | ||||

| Ointments/Creams α | |||||

| Household trash | 132 | 42.6% | Privately employed | 0.52 (0.28–0.97) | 0.039 |

| Burn | 21 | 6.8% | |||

| Flush down the toilet/sink | 9 | 2.9% | |||

| Return to health facility (hospital/pharmacy) | 9 | 2.9% | Higher education | 2.14 (1.18–3.88) | 0.012 |

| Others: FDA | 4 | 1.3% | |||

| Total (N) | 310 | ||||

| Suppositories/Vaginal Pessaries α | |||||

| Household trash | 105 | 33.9% | Older age | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | 0.035 |

| Burn | 11 | 3.5% | |||

| Return to health facility (hospital/pharmacy) | 8 | 2.6% | Higher education | 2.37 (1.29–4.35) | 0.005 |

| Flush down the toilet/sink | 10 | 3.2% | |||

| Others: FDA | 2 | 0.6% | |||

| Total (N) | 310 | ||||

| Attitude and Perception on Unused or Leftover Medicine Disposal | Agree | Disagree | Not Sure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Purchasing antimicrobials without a prescription can add to the number of unused medicines at home. | 273 (88.1%) | 21 (6.8%) | 16 (5.2%) | ||

| Is there adequate information on the safe disposal of unused antimicrobials from medicine manufacturers (inserts)? | 149 (48.1%) | 119 (38.4%) | 42 (13.5%) | ||

| Who do you think is/are responsible for creating awareness for the proper disposal of unused antimicrobials? * | Responses | ||||

| N | Percent | ||||

| Government agencies | 162 | 52.3% | |||

| Pharmaceutical industries | 219 | 70.6% | |||

| Public | 100 | 32.3% | |||

| Pharmacist | 223 | 71.9% | |||

| Other healthcare professionals | 183 | 59.0% | |||

| None of the above | 5 | 1.6% | |||

| Total | 310 | ||||

| Are you aware of institutions that collect unused medicines? | N | Percent | |||

| Yes | 76 | 24.5 | |||

| No | 234 | 75.5 | |||

| Total | 310 | 100.0 | |||

| If yes, which institutions do you know of? * | N | Percent | |||

| Government agencies (e.g., FDA) | 51 | 67.1% | |||

| Hospitals | 38 | 50.0% | |||

| Pharmacies | 43 | 56.6% | |||

| Others (Environmental Protection Agency, NGOs) | 10 | 13.2% | |||

| Total | 76 | ||||

| Have you ever participated in any medicine-return program? | Frequency | Percent | |||

| Yes | 25 | 8.1 | |||

| No | 228 | 73.5 | |||

| Not Aware | 57 | 18.4 | |||

| Total | 310 | 100.0 | |||

| Would you be willing to participate in a medicine-return program if it is available near you? | |||||

| Yes | 284 | 91.6% | |||

| No | 26 | 8.4% | |||

| Total | 310 | 100.0 | |||

| Take-back programs for unused/leftover medicines should be made mandatory. | |||||

| Agree | 199 | 64.2% | |||

| Disagree | 78 | 25.2% | |||

| Not sure | 33 | 10.6% | |||

| Total | 310 | 100.0 | |||

| Where would you prefer to return your unused/leftover antimicrobials? * | N | Percent | |||

| Community pharmacy | 160 | 51.6% | |||

| Hospital/CHPS facility | 154 | 49.7% | |||

| Home pickup | 105 | 33.9% | |||

| Shopping mall/supermarket | 21 | 6.8% | |||

| None of the above | 27 | 8.7% | |||

| Total | 310 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aku, T.A.; Jato, J.; Atsu, L.D.; Oteng, D.; Ben, I.O.; Somuah, S.O.; Odoi, H.; Orman, E.; Dodoo, C.; Jani, Y.; et al. Knowledge and Practices on Household Disposal of Unused Antimicrobials in Ho Municipality, Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101519

Aku TA, Jato J, Atsu LD, Oteng D, Ben IO, Somuah SO, Odoi H, Orman E, Dodoo C, Jani Y, et al. Knowledge and Practices on Household Disposal of Unused Antimicrobials in Ho Municipality, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101519

Chicago/Turabian StyleAku, Thelma Alalbila, Jonathan Jato, Lawrencia Dogbeda Atsu, David Oteng, Inemesit Okon Ben, Samuel Owusu Somuah, Hayford Odoi, Emmanuel Orman, Cornelius Dodoo, Yogini Jani, and et al. 2025. "Knowledge and Practices on Household Disposal of Unused Antimicrobials in Ho Municipality, Ghana" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101519

APA StyleAku, T. A., Jato, J., Atsu, L. D., Oteng, D., Ben, I. O., Somuah, S. O., Odoi, H., Orman, E., Dodoo, C., Jani, Y., & Hutton-Nyameaye, A. A. (2025). Knowledge and Practices on Household Disposal of Unused Antimicrobials in Ho Municipality, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101519