The Psychology of Sports Injuries in Children and Adolescents: Psychosocial, Developmental, and Recovery Aspects to Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

Sports Injury as Perceived by Athletes and Trainers

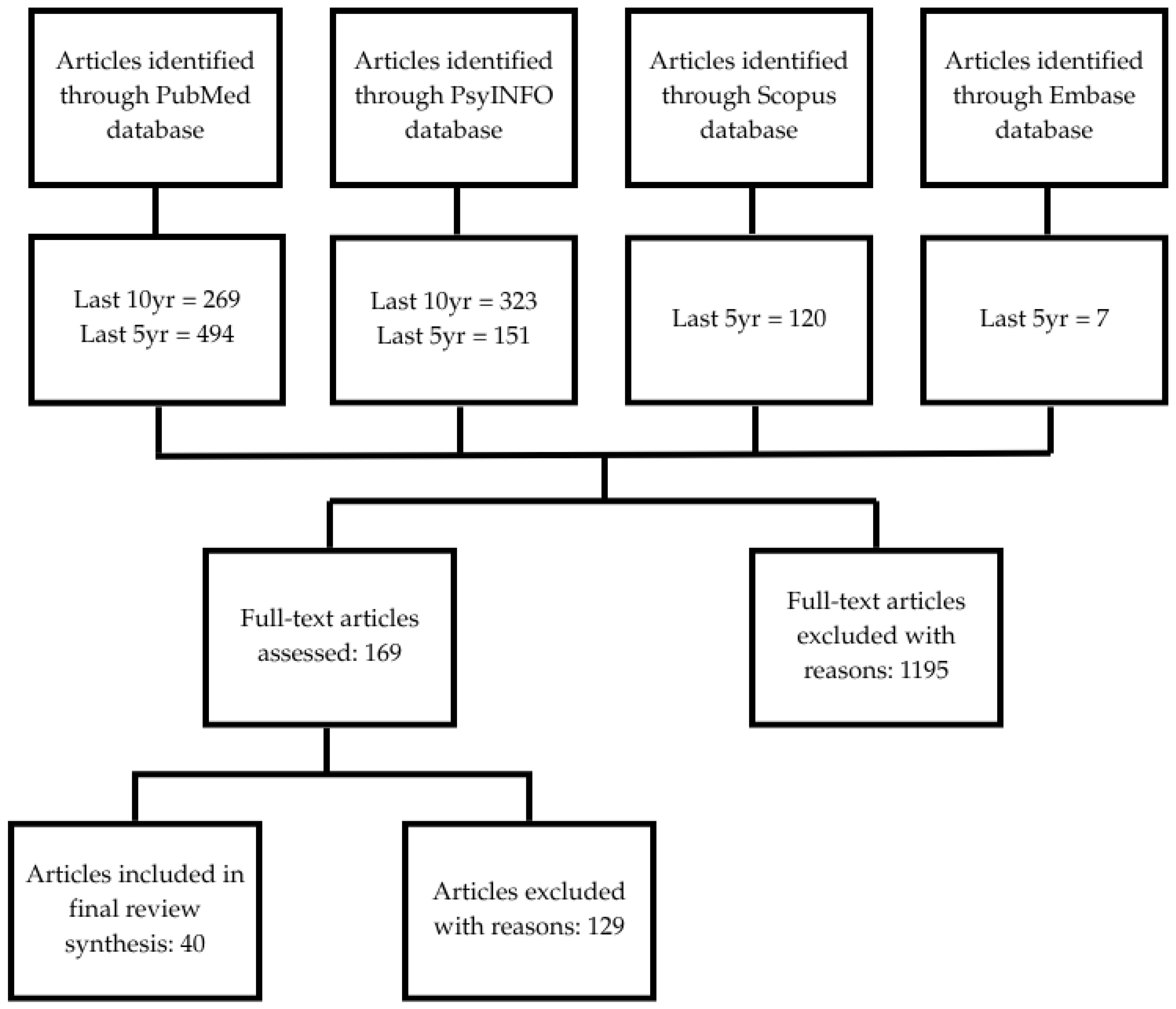

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Search

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Developmental Aspects

3.2. Predisposing and Risk Factors for Injuries

3.2.1. Sex

3.2.2. Type of Sport Activity

3.2.3. Previous Conditions and Injuries

3.3. Psychosocial Factors and Stressors

3.4. Models of Sports Injury and Mental Health

3.4.1. Stress-Injury Model

3.4.2. Integrated Model of Psychological Response to the Sport Injury and Rehabilitation Process

3.5. Recovery

3.6. Role of Training and Conditioning

3.7. Medical Professionals’ Roles in Sports Injury Rehabilitation

4. Discussion

4.1. Educational Intervention in Psychology of Injury

4.2. Behavioral Health Interventions in Psychology of Injury

4.2.1. Psychoeducation

4.2.2. Skills-Training

4.2.3. Maintenance

5. Conclusions

Research Gaps

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| AT | Athletic trainer |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| ACL | Anterior cruciate ligament |

| SMP | Sports medicine professional |

| ATS | Athletic training students |

| CBT | Cognitive behavior therapy |

| MBSR | Mindfulness-based stress reduction |

| ACT | Acceptance and commitment therapy |

References

- Codner, M.; Ames, C.; Pluhar, E.I. The psychological effects of injury on youth athletes. In Psychological Considerations in the Youth Athlete: A Multidisciplinary Approach; Christino, M.A., Pluhar, E.I., Micheli, L.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, L.; Li, D. Psychological well-being from sports injuries in adolescence: A narrative review. Cureus 2024, 16, e64018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, E. Athlete mental health & psychological impact of sport injury. Oper. Tech. Sports Med. 2022, 30, 150898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindman, I.; Ryman Augustsson, S.; Baranto, A.; Sansone, M.; Abrahamson, J. Prospective cohort study identifying risk factors for sports injuries in adolescent athletes: The Health Injury-Free Adolescent Athletes (HIFAA) study. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2024, 10, e002253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseid, C.H.; Myklebust, G.; Fargerland, M.W.; Clarsen, B.; Bahr, R. The prevalence and severity of health problems in youth elite sports: A 6-month prospective cohort study of 320 athletes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiller-Ostrowski, J.L.; Gould, D.R.; Covassin, T. An evaluation of an educational intervention in psychology of injury for athletic training students. J. Athl. Train. 2009, 44, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsdottir, K.; Watson, A.M. Psychosocial impacts of sports-related injuries in adolescent athletes. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2021, 20, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Patel, D.R.; Darmawan, D. Participation in sports in relation to adolescent growth and development. Transl. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, M.E.; Walter, K.D.; Moffatt, K. Sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20183074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iverson, G.L.; Berkner, P.D.; Zafonte, R.; Maxwell, B.; Terry, D.P. Preseason symptom reporting and cognition in middle school athletes with past concussions. Int. J. Sports Med. 2022, 43, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.A.; Schneider, K.J.; Anderson, V.; Babl, F.E.; Barlow, K.M.; Blauwet, C.A.; Bressan, S.; Broglio, S.P.; Emery, C.A.; Echemendia, R.J.; et al. Pediatric Sport-Related Concussion: Recommendations From the Amsterdam Consensus Statement 2023. Pediatrics 2023, 153, e2023063489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padaki, A.S.; Noticewala, M.S.; Levine, W.N.; Ahmad, C.S.; Popkin, M.K.; Popkin, C.A. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among young athletes after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2018, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, M.M.; Reardon, C.L. Mental health in the youth athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2024, 43, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecklund, K. Sports-related injuries of the pediatric musculoskeleton: Lower extremity. In Musculoskeletal Diseases 2021-2024: Diagnostic Imaging; Hodler, J., Kubik-Huch, R.A., von Schulthess, G.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliason, P.H.; Galarneau, J.M.; Babul, S.; Mrazik, M.; Bonfield, S.; Schneider, K.J.; Hagel, B.E.; Emery, C.A. Safe2Play in youth ice hockey: Injury profile and risk factors in a 5-year Canadian longitudinal cohort study. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2385024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, M.A.; Allajhar, M.A.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Asiri, M.A.; Alsalem, A.F.; Alshahrani, S.A.; Alqahtani, N.M. Sports-related injuries in adolescent athletes: A systematic review. Cureus 2023, 15, e49392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, M.; Pasanen, K.; Kannus, P.; Vasankari, T.; Kujala, U.M.; Heinonen, A.; Parkkari, J. Epidemiology of overuse injuries in youth team sports: A 3-year prospective study. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardaker, N.J.; Hume, P.A.; Sims, S.T. Differences in injury profiles between female and male athletes across the participant classification framework: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 1595–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.L.; Attia, M.W. Sports-related injuries in children. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2000, 7, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterno, M.V.; Taylor-Haas, J.A.; Myer, G.D.; Hewett, T.E. Prevention of overuse sports injuries in the young athlete. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2013, 44, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, S.; Erdman, A.; McGinley, J.; Loewen, A.; Ellis, H.B.; Wyatt, C.; Jones, J.C.; Miller, S.M.; Wilson, P.L.; Ulman, S. The relationship between Beighton score and biomechanical risk factors among adolescent, female volleyball players. Phys. Ther. Sport. 2024, 70, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, T.; Mitchell, I.; Evans, L.; Hardy, L. Stressors, social support and psychological responses to sport injury in high- and low-performance standard participants. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, I.W.; Eklund, R.C.; Gordon, S. An examination of psychosocial variables moderating the relationship between life stress and injury time-loss among athletes of a high standard. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, D.; Granquist, M.D.; Arvinen-Barrow, M.M. Psychosocial aspects of athletic injuries as perceived by athletic trainers. J. Athl. Train. 2013, 48, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, A.L.; Giorgi, B. The experience of self-discovery and mental change in female novice athletes in connection to marathon running. J. Phenomen. Psychol. 2010, 41, 234–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, B.W.; Chatterton, H.A. Athletic Identity and Sport Injury Processes and Outcomes in Young Athletes: A Supplemental Narrative Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Andersen, M.B. Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury: Review and critique of the stress and injury model’. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1998, 10, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese-bjornstal, D.M.; Smith, A.M.; Shaffer, S.M.; Morrey, M.A. An integrated model of response to sport injury: Psychological and sociological dynamics. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1998, 10, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahe, K.; Burrichter, K. The role of psychological resilience in athletic injury recovery and performance. Rev. De Psicol. íA Del Deporte. 2023, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, D.; Arvinen-Barrow, M.M.; Fetty, T. Psychosocial responses during different phases of sport-injury rehabilitation: A qualitative study. J. Athl. Train. 2015, 50, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putukian, M. The psychological response to injury in student athletes: A narrative review with a focus on mental health. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvinen-Barrow, M.M.; Massey, W.V.; Hemmings, B. Role of sport medicine professionals in addressing psychosocial aspects of sport-injury rehabilitation: Professional athletes’ views. J. Athl. Train. 2014, 49, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørndal, C.T.; Hausken-Sutter, S.; Møller, M.; Myklebust, G.; Grindem, H. Exploring the interplay of interpersonal and contextual dynamics in youth sports injuries: A comprehensive narrative review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachazewski, J.; Magee, D.; Quillen, W. Athletic Injuries and Rehabilitation; W B Saunders Co., Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 78, pp. 434–435. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, D.R.; Yamasaki, A.; Brown, K. Epidemiology of sports-related musculoskeletal injuries in young athletes in United States. Transl. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoar, S.D.; Flint, F. Determinants of help-seeking intentions in the context of athletic injury recovery. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 6, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharadze, D.; Abramov, A.; Konovalov, O.; Fomina, A.; Generalova, Y.; Kakabadze, E.; Bokova, E.; Shegai, A.; Kozlova, Z.; Fokina, S. Medical and social aspects of preventing sports injuries among children and adolescents. Georgian Med. News 2023, 344, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, J.S.; Watson, A. Council on sports medicine and fitness: Overuse injuries, overtraining, and burnout in young athletes. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023065129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsbo, J.; Elbe, A.M.; Anderson, M.; Poulsen, A.L. Performance in top sports involving intense exercise. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheinbein, S. Psychological effect of injury on the athlete: A recommendation for psychological intervention. AMAA J. 2016, 29, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoang, L.-N.; Joshi, P.; Patel, D.R.; Apple, R.W. The Psychology of Sports Injuries in Children and Adolescents: Psychosocial, Developmental, and Recovery Aspects to Injury. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101509

Hoang L-N, Joshi P, Patel DR, Apple RW. The Psychology of Sports Injuries in Children and Adolescents: Psychosocial, Developmental, and Recovery Aspects to Injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101509

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoang, Linh-Nhu, Pradnya Joshi, Dilip R. Patel, and Roger W. Apple. 2025. "The Psychology of Sports Injuries in Children and Adolescents: Psychosocial, Developmental, and Recovery Aspects to Injury" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101509

APA StyleHoang, L.-N., Joshi, P., Patel, D. R., & Apple, R. W. (2025). The Psychology of Sports Injuries in Children and Adolescents: Psychosocial, Developmental, and Recovery Aspects to Injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101509