Breaking the Silence: A Scoping Literature Review on Trauma-Informed Care for Black Women Navigating Sexual Health-Related Trauma

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Contextualizing Sexual Health-Related Trauma Among Black Women

1.2. Sociocultural Barriers

1.3. Systemic Inequities Across Healthcare and Legal Sysems

1.4. Socio-Economic Barriers

2. TIC Framework

2.1. Safety

2.2. Trustworthiness and Transparency

2.3. Peer Support

2.4. Collaboration and Mutuality

2.5. Empowerment, Voice, and Choice

2.6. Recognition of Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues

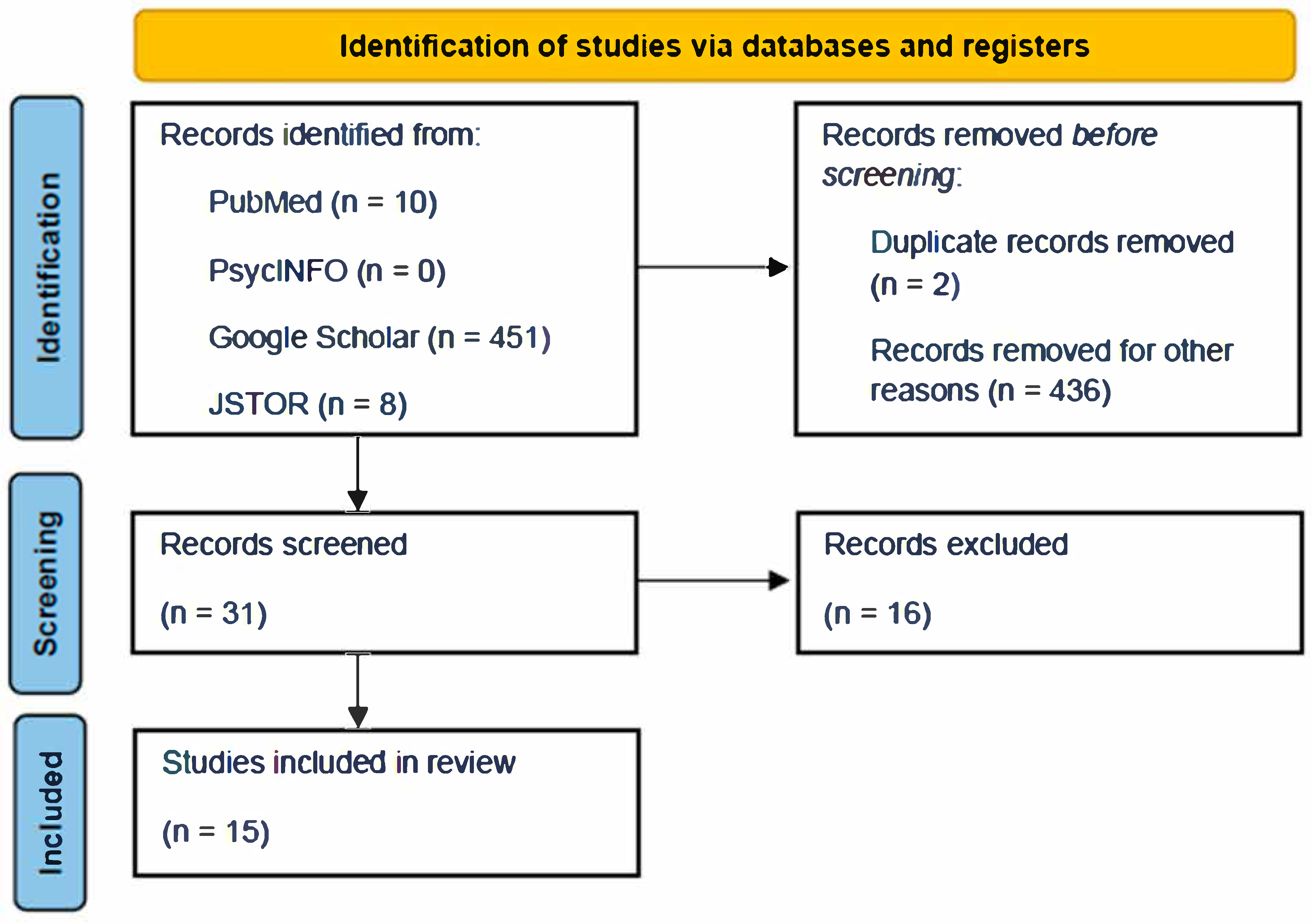

3. Methods

4. Literature Review Themes

4.1. Barriers to Accessing Mental Health Treatment

4.2. Culturally Responsive TIC

4.3. Trauma Predicts Risk: Mental Health Distress, Substance Use, and Sexual Health Vulnerabilities

4.4. Implications for Practice and Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berring, L.L.; Holm, T.; Hansen, J.P.; Delcomyn, C.L.; Søndergaard, R.; Hvidhjelm, J. Implementing trauma-informed care-settings, definitions, interventions, measures, and implementation across settings: A scoping review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Trauma-Informed Approaches and Programs. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/mental-health/trauma-violence/trauma-informed-approaches-programs (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Raghavan, S.; Sandanapitchai, P. The relationship between cultural variables and resilience to psychological trauma: A systematic review of the literature. Traumatology 2024, 30, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jieman, A.T.; Soliman, F.; York, K.; Bhui, K.; Onwumere, J.; Wynter, S.; Amasowomwan, F.; Johnson, S.; Jones, J.M. Black women’s lived experiences of depression and related barriers and facilitators to utilising healthcare services: A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis co-produced with experts by lived experiences. medRxiv 2024, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, A.I.; Murphy, C.M.; Davis, M.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. Racial discrimination, mental health symptoms, and intimate partner violence perpetration in Black adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 90, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, K.; Parnell, R.; Mouzon, D.; Matusko, N.; Head, D.; Abelson, J.; Jackson, J. The mental health of us black women: The roles of social context and severe intimate partner violence. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelman, L.; Salim, S.; Bhuptani, P.; Saad, M. Sexual objectification racial microaggressions amplify the positive relation between sexual assault and posttraumatic stress among black women. Psychol. Women Q. 2023, 48, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K.; Morgan, I.; Davis, K.; Estriplet, T.; Perez, S.; Crear-Perry, J. Pathways to equitable and antiracist maternal mental health care: Insights from black women stakeholders. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeal, R.; Harris, M.; Oliphant, V. Re-envisioning community-engaged healing for Black women. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2024, 26, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Prather, C.; Fuller, T.R.; Jeffries, W.L., IV; Marshall, K.J.; Howell, A.V.; Belyue-Umole, A.; King, W. Racism, African American women, and their sexual and reproductive health: A review of historical and contemporary evidence and implications for health equity. Health Equity 2018, 2, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, J.J.; Martin, I.K.; Redmond, N. Health equity among Black women in the United States. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, C.T.; Bryant-Davis, T.; Woodward, H.E.; Tillman, S.; Torres, S.E. Intimate partner violence against African American women: An examination of the socio-cultural context. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2009, 14, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D. The paradox of silence and display: Sexual violation of enslaved women and contemporary contradictions in Black female sexuality. In Beyond Slavery: Overcoming Its Religious and Sexual Legacies; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseborough, T.; Overstreet, N.; Ward, L.M. Interpersonal sexual objectification, Jezebel stereotype endorsement, and justification of intimate partner violence toward women. Psychol. Women Q. 2020, 44, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Melson-Silimon, A.; Spivey, B.N.; Skinner-Dorkenoo, A.L. The construction of racial stereotypes and how they serve as racial propaganda. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2024, 18, e12862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Perry, M.V. Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, N.; Barrie, R.; Singer, R.; Donenberg, G. The role of the strong black woman in Black female sexual development. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 52, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subhan, B.A.; Johnson, V.E. The Strong Black Woman Archetype and therapeutic outcomes: Examining relationships among women with childhood sexual abuse histories. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, L.; Lobel, M. Stereotypes of Black American women related to sexuality and motherhood. Psychol. Women Q. 2016, 40, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.C.; Prock, K.A. “I still feel like I am not normal”: A review of the role of stigma and stigmatization among female survivors of child sexual abuse, sexual assault, and intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, S.; Bryant-Davis, T.; Smith, K.; Marks, A. Shattering silence: Exploring barriers to disclosure for African American sexual assault survivors. Trauma Violence Abus. 2010, 11, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.M.; Gobin, R.L. Black women and girls &# MeToo: Rape, cultural betrayal, & healing. Sex Roles 2020, 82, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis, T.; Ullman, S.E.; Tsong, Y.; Gobin, R. Surviving the storm: The role of social support and religious coping in sexual assault recovery of African American women. Violence Against Women 2011, 17, 1601–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, B.D.; Stith, A.Y.; Nelson, A.R. Patient-provider communication: The effect of race and ethnicity on process and outcomes of healthcare. In Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, A.; Woods-Jaeger, B.; Stevens, J.S.; Bradley, B.; Patel, M.B.; Joyner, A.; Smith, A.K.; Jamieson, D.J.; Kaslow, N.; Michopoulos, V. Trauma, psychiatric disorders, and treatment history among pregnant African American women. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Tillaart, S.; Kurtz, D.; Cash, P. Powerlessness, marginalized identity, and silencing of health concerns: Voiced realities of women living with a mental health diagnosis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 18, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.L. Understanding the hidden struggles: Cultural and somatic expressions of depression and anxiety in Black women. Women Health Care Issues 2024, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley, A.L. Cultural mistrust: An important psychological construct for diagnosis and treatment of African Americans. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2001, 32, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, E. A synthesis of the literature on trauma-informed care. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 36, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, H.; Combs, R.; Lorenz, K.; Harris, L.; Wendel, M. Reimagining support after sexual violence: Survivors’ recommendations for community-based support organizations. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2025, 51, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra-Gupta, S.; Petruzzi, L.; Jones, C.; Cubbin, C. An intersectional approach to understanding barriers to healthcare for women. J. Community Health 2023, 48, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpless, L.; Kershaw, T.; Knight, D.; Campbell, J.K.; Phillips, K.; Katague, M.; Willie, T.C. Moving towards transformative justice for black women survivors of intimate partner violence: An intersectional qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovinsky, T.L. The thread of trauma: A critical analysis of the criminal legal system. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Swint, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. Mind the gap: Unraveling mental health disparities in America’s diverse landscape. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willie, T.C.; Phillips, K.; Shah, A.; Monger, M.M.; Nunn, A.; Kershaw, T.; Chan, P.A.; Baral, S.D.; Mayer, K.H.; Adimora, A.A.; et al. Perspectives on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) implementation in Mississippi among Black women and clinical staff: Recommendations for clinical trauma-informed programs. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 36, 102490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnoli, A. Historical primer on obstetrics and gynecology health inequities in America: A narrative review of four events. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptiste, D.L.; Caviness-Ashe, N.; Josiah, N.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Arscott, J.; Wilson, P.R.; Starks, S. Henrietta Lacks and America’s dark history of research involving African Americans. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, S.L. Creating Sanctuary: Toward the Evolution of Sane Societies, Revised ed.; Routledge, Taylor and Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.S. Cultural Competence in Trauma Therapy: Beyond the Flashback; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.N.; Hackman, A.L. Trust and mistrust of mental health services among Black adults. Psychiatr. Serv. 2025, 76, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, A.; Randall, J. “We’re not taken seriously”: Describing the experiences of perceived discrimination in medical settings for black women. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morera-Balaguer, J.; Botella-Rico, J.M.; Martínez-González, M.C.; Medina-Mirapeix, F.; Rodríguez-Nogueira, Ó. Physical therapists’ perceptions and experiences about barriers and facilitators of therapeutic patient-centred relationships during outpatient rehabilitation: A qualitative study. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2018, 22, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant-Davis, T.; Fasalojo, B.; Arounian, A.; Jackson, K.L.; Leithman, E. Resist and rise: A trauma-informed womanist model for group therapy. Women Ther. 2021, 47, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutowski, E.R.; Badio, K.S.; Kaslow, N.J. Trauma-informed inpatient care for marginalized women. Psychotherapy 2022, 59, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Fauci, J.E.; Goodman, L.A. Bringing trauma-informed practice to domestic violence programs: A qualitative analysis of current approaches. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2015, 85, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Díaz, L. Racial trauma recovery: A race-informed therapeutic approach to racial wounds. In The Cost of Racism for People of Color: Contextualizing Experiences of Discrimination; Alvarez, A.N., Liang, C.T.H., Neville, H.A., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amwiine, E.; Ainembabazi, B.; Obwona, I.; Opoka, R.; Akatuhumuriza, M.; Niyonzima, V.; Mubangizi, V. Perceptions of females about trauma-informed services for survivors of sexual violence in south western Uganda—A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catabay, C.J.; Stockman, J.K.; Campbell, J.C.; Tsuyuki, K. Perceived stress and mental health: The mediating roles of social support and resilience among black women exposed to sexual violence. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.Y.; Johnson, V.; Conyers, L.M. Exploring the impact of an integrated trauma-informed HIV and vocational intervention for Black/African American women living with HIV. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, V.; Lindinger-Sternart, S.; MacDonald, D.A.; Martin, T. The interrelatedness of trauma, substance use, and the social determinants of health in Black women. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 2025, 43, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.; Carney, T.; Browne, F.A.; Wechsberg, W.M. A trauma-informed substance use and sexual risk reduction intervention for young South African women: A mixed-methods feasibility study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, S.E.; Abbey, A. Associations between sexual assault severity and psychological and physical health outcomes: Similarities and differences among African American and caucasian survivors. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 4020–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricks, J.M.; Horan, J. Associations between childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence trauma exposure, mental health, and social gender affirmation among Blacktransgender women. Health Equity 2023, 7, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, D.A. Ain’t I a Survivor Too: Contextualizing Black Women’s Experience of Sexual Trauma and Healing. Ph.D. Thesis, Antioch University, Yellow Springs, OH, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, A.D.F.; Cimino, A.N.; Balthazar, M.; Johnson, K.B.; Burns, D.D.; Verissimo, A.D.O.; Campbell, J.C.; Tsuyuki, K.; Stockman, J.K. Discrimination, sexual violence, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and social support among Black women. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2023, 34, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkema, K.J.; Mulawa, M.I.; Robertson, C.; Watt, M.H.; Ciya, N.; Stein, D.J.; Cherenack, E.M.; Choi, K.W.; Kombora, M.; Joska, J.A. Improving AIDS Care After Trauma (ImpACT): Pilot outcomes of a coping intervention among HIV-infected women with sexual trauma in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockman, J.K.; Anderson, K.M.; DeSoto, A.F.; Campbell, D.M.; Tsuyuki, K.; Horvath, K.J. A trauma-informed HIV intervention (LinkPositively) to improve HIV care among Black women affected by interpersonal violence: Protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e46325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullman, S.E.; Lorenz, K. African American sexual assault survivors and mental health help-seeking: A mixed methods study. Violence Against Women 2020, 26, 1941–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.A.; Choi, J.; Capasso, A.; DiClemente, R. Association of trauma history with current psychosocial health outcomes of young African American women. Youth 2024, 4, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit-Toledo, M.T. Collective memory and intersectional identities: Healing unique sexual violence harms against women of color past, present and future. Univ. Hawaiʻi Law Rev. 2022, 45, 346. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S. Trauma-informed cultural humility mental health practice: Centering history among African American women. Soc. Work 2024, 69, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author(s) | Origin | Study Type | Sample (N) | Methods | Setting | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amwiine et al. (2021) [49] | Uganda | Descriptive cross-sectional study qualitative design | 32 females | Interviews | Kyangyenyi health center III and Kigarama health center III in Sheema district, southwestern Uganda | After assessing the knowledge of participants for trauma-informed services (TIS), the participants’ attitudes towards TIS, and different factors associated with the utilization of TIS, it was concluded that there was a knowledge gap about TIS and that sensitization needs to be done about this service |

| Catabay et al. (2019) [50] | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional study | 161 women | Self-report surveys | Community Based | Black women ages 18–44 with a history of sexual violence reported high levels of perceived stress, which were directly linked to symptoms of depression and anxiety. The presence of strong social support and personal resilience helped lessen the impact of stress on their mental health. Women with more support and higher resilience had better overall outcomes |

| Chang et al. (2023) [51] | USA | Mixed Methods | 21 cisgender females | Quantitative surveys, Qualitative interviews | Community-based | Participants showed a decrease in trauma symptoms and increased confidence in managing their health and employment goals. Engagement in both HIV care and vocational services improved |

| Decker et al. (2025) [31] | USA | Qualitative | 20 adults (15 Caucasian, 2 African American, 3 biracial, 2 AA/Caucasian, 1 Caucasian/Hispanic) | Semi-structured interviews | Recruited on social media (Facebook and Instagram) to take part in virtual interviews | Community-based organizations are important to address the health and support needs of survivors of sexual violence, and there are opportunities for areas of improvement in these organizations |

| Kaur et al. (2025) [52] | USA | Qualitative | 12 Black women | Interviews | Community-based interviews | The study highlighted that childhood sexual abuse and intimate partner violence, significantly influences substance use behaviors among Black women. Additionally, social determinants of health, such as economic instability and access to healthcare, were found to play a crucial role in shaping health outcomes and coping mechanisms |

| Myers et al. (2019) [53] | South Africa | Mixed methods | 60 | Single-arm feasibility test and interviews via a group-based intervention | Community-based interviews | Participants reported reductions in substance use (methamphetamine, cannabis, and methaqualone), sexual risk behaviors (fewer sexual partners and less condomless sex), and symptoms of trauma-related mental health concerns, including depression, PTSD, and psychological distress |

| Pegram & Abbey (2019) [54] | USA (suburban and semi-rural communities in southeastern Michigan) | Quantitative study | 221 participants (121 African American and 100 Caucasian women) | Standardized self-report measures | In-person interviews in various settings (e.g., participants’ homes, restaurants, coffee shops) | Examines racial differences in psychological and physical health outcomes among sexual assault survivors and highlights the need for racially responsive trauma-informed care |

| Ricks et al. (2023) [55] | USA | Mixed Methods | 138 Black trans women | Interviews | In-person structured interviews | Black transgender women in the study reported high rates of childhood sexual abuse and intimate partner violence. Social gender affirmation was associated with improved mental health outcomes, but these benefits were weakened by recent or lifetime experiences of IPV |

| Samuel (2024) [56] | USA | Mixed methods | 98 Black women | Rating scales and interviews | Online | Explores Black women’s experiences of sexual trauma and healing and emphasizes the role of racialized stressors and culturally specific coping strategies |

| Sherman et al. (2023) [57] | USA | Analyzation of cross-sectional data from a retrospective cohort study | 236 Black women | Assisted self-interview | Recruited from STD clinics | Explores the exacerbation of mental health disorders associated with sexual victimization amongst black women |

| Sikkema et al. (2018) [58] | Cape Town, South Africa | Pilot clinical trial | 64 women | Psychological intervention sessions | Primary health care clinic | Evaluated the feasibility of a coping intervention for HIV infected women with sexual abuse histories, preliminary findings show potential to reduce PTSD symptoms and increase ART adherence motivation |

| Stockman et al. (2023) [59] | USA | Pilot randomized control trial | 80 Black women | LinkPositively intervention (mobile app) | In-person and online | Evaluated the feasibility of LinkPositively, a trauma-informed, tech-based HIV care intervention for Black women affected by interpersonal violence; found high acceptability and preliminary improvements in care engagement and treatment adherence |

| Ullman & Lorenz (2020) [60] | USA | Mixed methods | 836 African American women | Standardized self-report measures and structured interviews | Surveys distributed via mail; interviews conducted in-person | Explored mental health help-seeking among African American sexual assault survivors, identifying key barriers including stigma, mistrust, and provider bias, and highlighting the importance of culturally sensitive care |

| Willie et al. (2023) [36] | USA | Qualitative | 44 (37 Black women participants and 7 clinical staff members) | Semi-structured interviews | Community healthcare clinics | Identified key components for trauma-informed PrEP implementation based on perspectives from Black women and clinical staff in Mississippi; emphasized intimate partner violence (IPV) screening, staff training, and culturally relevant care |

| Xu et al. (2024) [61] | USA | Cross-sectional study | 560 African American women | Standardized self-report measures administered via Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) | Community locations (e.g., beauty salons, shopping malls) | Assessed associations between trauma history and adverse psychosocial outcomes among young African American women; found that trauma was linked to higher substance misuse, risky sexual behavior, IPV, and poor mental health |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Troutman, A.; Are, F.; Okoye, A.; Chiang, S.; Craig, D.; Akande, A.; Stafford, I. Breaking the Silence: A Scoping Literature Review on Trauma-Informed Care for Black Women Navigating Sexual Health-Related Trauma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101484

Troutman A, Are F, Okoye A, Chiang S, Craig D, Akande A, Stafford I. Breaking the Silence: A Scoping Literature Review on Trauma-Informed Care for Black Women Navigating Sexual Health-Related Trauma. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101484

Chicago/Turabian StyleTroutman, Ayanna, Funlola Are, Ashley Okoye, Sarah Chiang, Destiny Craig, Anthony Akande, and Irene Stafford. 2025. "Breaking the Silence: A Scoping Literature Review on Trauma-Informed Care for Black Women Navigating Sexual Health-Related Trauma" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101484

APA StyleTroutman, A., Are, F., Okoye, A., Chiang, S., Craig, D., Akande, A., & Stafford, I. (2025). Breaking the Silence: A Scoping Literature Review on Trauma-Informed Care for Black Women Navigating Sexual Health-Related Trauma. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1484. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101484