Patient-Centered Leadership and Co-Design of Services for Breast Cancer Program in Nicaragua

Abstract

1. Introduction

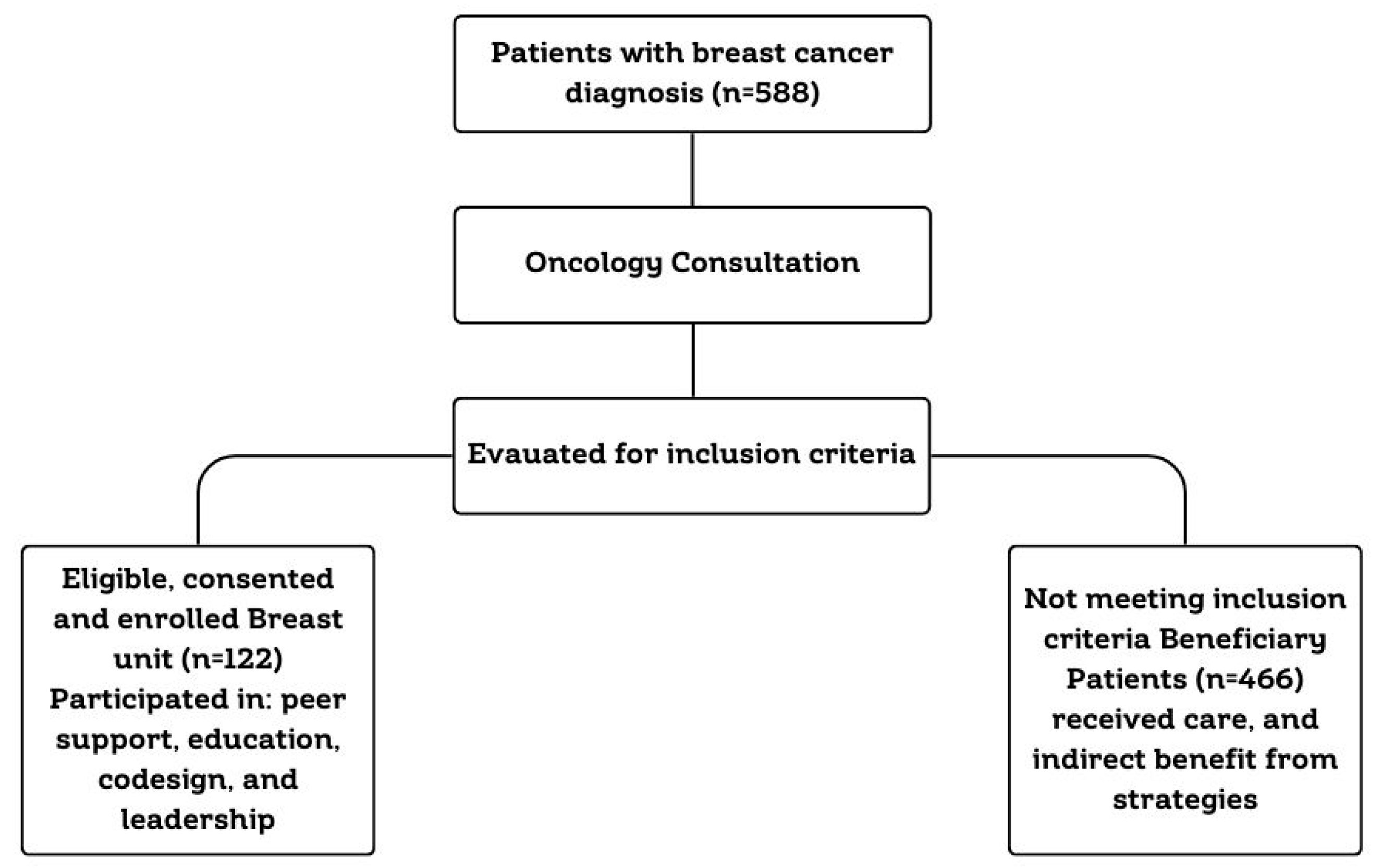

2. Materials and Methods

- Personal conversations between patients, calls to support each other.

- Attending weekly educational sessions to become permanent educators for their peers.

- Participating in technical committees to enhance patient safety and quality of care.

- Collaborating in the development and revision of educational materials, policies, and web resources.

- Providing recommendations to support the prevention of medical errors.

- Promoting activities related to Breast Cancer Awareness Month (October) within the institution, coordinating with and involving the Breast Unit’s support group.

- Organizing an activity commemorating Nicaraguan Mother’s Day (May 30th).

- Inspiration: Through structured meetings with hospital directors and multidisciplinary teams, patients shared their lived experiences, challenges, and unmet needs, providing critical insights into the realities of breast cancer care.

- Ideation: Patient feedback was instrumental in generating innovative ideas and practical solutions aimed at improving medical assistance, psychosocial support, and care coordination for breast cancer patients.

- Implementation: Patients assumed leadership roles in executing health strategies, ensuring that interventions were grounded in real-world relevance and tailored to the diverse needs of the breast cancer community.

2.1. Data Analysis

- n = required sample size

- N = population size

- p = expected frequency (proportion)

- d = desired precision (margin of error)

- Z = Z-score corresponding to the selected confidence level

- DEFF = design effect

2.2. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Patient Leadership

- Patient as a group leader: Patients with extensive diagnosis and treatment experience who mentored new members. This fostered immediate trust and relatability that professional healthcare providers, despite their expertise, cannot always replicate. This shared experience created a safe space for open dialogue.

- Talk facilitators: Patients trained in specific topics who shared information with peers who promoted improved adherence to medications, earlier symptom recognition and management, lifestyle modifications, and follow-up appointments. They profoundly influenced the knowledge, confidence, and active participation of their peers.

- Event coordinators: Responsible for organizing and managing special activities, such as Breast Cancer Awareness Month events. This was far more than an administrative delegation; it was a strategic investment in people-centered care. By leveraging their unique insights and passion, these patient leaders significantly enhanced awareness, built vital community support, and empowered their peers in their self-care.

- Advocacy voices: Group representatives who participated in forums, conferences, and outreach activities both within and outside the hospital. These patients were the embodiment of people-centered care in action. They ensure that the healthcare system was not just treating a disease but truly serving the individuals living with it, leading to more relevant, accessible, and ultimately, more effective care and improved outcomes. The patient voice was present in leadership sessions for feedback.

3.2. Co-Design and Human-Centered Innovation

3.3. Multidisciplinary Collaboration Enhanced by Patient Insight

3.4. Psychosocial Impact and Emotional Resilience

- Understanding Your Diagnosis: Simplified explanations to help patients prepare for treatment, manage side effects, and recognize warning signs.

- Mental Health and Emotional Strength: Strategies to build resilience and maintain psychological well-being.

- Family and Social Support: Emphasis on the importance of a strong support network in navigating the cancer journey.

- Spirituality as a Refuge: Reflections on how faith and personal beliefs can provide comfort and peace during treatment.

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Components | Description |

|---|---|

| Institution | Dr. Alejandro Dávila Bolaños Military Teaching Hospital (HMEADB) |

| Primary Focus | Patient leadership, co-design, Breast cancer care and support |

| Study Groups |

|

| Timeframe | June 2022–2024 |

| Frameworks Used |

|

| Inclusion Criteria (Breast Unit) |

|

| Implementation Strategy |

|

| Multidisciplinary Team | Mastologists, Oncologists, Psychologists, Nutritionists, Physiotherapists, Plastic Surgeons, and expert patients for feedback. |

| Patient Activities |

|

| Co-design Contributions |

|

| Impact Measurement (Breast Unit) |

|

| Impact Measurement (Beneficiary Group) |

|

References

- Hernández Silva, M.A.; Ruiz Martínez, A.O.; González Escobar, S.; González-Celis Rangel, A.L.M. Ansiedad, Depresión y Estrés asociados a la Calidad de Vida de Mujeres con Cáncer de Mama. Acta Investig. Psicológica 2020, 10, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella-Castillo, D.; Pech-Argüelles, R.C.; Olais-Arjona, I.; Rubio-Zapata, H.; Leal-Herrera, Y.A. Scientific evidence of the relation between breast cancer and depression: Systematic review. Rev. Medica Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2020, 58 (Suppl. 1), S91–S96. [Google Scholar]

- Bickell, N.A.; Moss, A.D.; Castaldi, M.; Shah, A.; Sickles, A.; Pappas, P.; Lewis, T.; Kemeny, M.; Arora, S.; Schleicher, L.; et al. Organizational factors affect safety-net Hospitals’ breast cancer treatment rates. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 52, 2137–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared decision making—Pinnacle of patient-centered care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNaDM México. Empoderamiento y Participación Social. Unidad 2. 2017. Available online: https://dmd.unadmexico.mx/contenidos/DCSBA/BLOQUE2/PES/05/FPSE/unidad_02/descargables/FPSE_U2_Contenido.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Tanay, M.A.L.; Armes, J.; Oakley, C.; Sage, L.; Tanner, D.; Roca, J.; Bryson, L.; Greenall, B.; Urwin, L.; Wyatt, T. Co-designing a cancer care intervention: Reflections of participants and a doctoral researcher on roles and contributions. Res. Involv. Engag. 2022, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, N.; Jongebloed, H.; Baguley, B.; Marshall, S.; White, V.M.; Livingston, P.M.; Bell, K.; Young, L.; Sabesan, S.; Swiatek, D.; et al. Meaningful consumer involvement in cancer care: A systematic review on co-design methods and processes. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkae048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlait, M.; Baes, S.; Dhaene, S.; Van Belle, S.; Leys, M. How multidisciplinary are multidisciplinary team meetings in cancer care? An observational study in oncology departments in Flanders, Belgium. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2019, 12, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, R.; Morgese, F.; Rinaldi, S.; Torniai, M.; Mentrasti, G.; Scortichini, L.; Giampieri, R. Benefits and Limitations of a Multidisciplinary Approach in Cancer Patient Management. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 9363–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermes-Moll, K.; Dengler, R.; Riese, C.; Baumann, W. Tumor Boards from the Perspective of Ambulant Oncological Care. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2016, 39, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospital Militar. 2025. Available online: https://www.hospitalmilitar.com.ni/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Phillips, R.L.; Short, A.; Kenning, A.; Dugdale, P.; Nugus, P.; McGowan, R.; Greenfield, D. Achieving patient-centred care: The potential and challenge of the patient-as-professional role. Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2015, 18, 2616–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, G.; Cornwell, J.; Locock, L.; Purushotham, A.; Sturmey, G.; Gager, M. Patients and staff as codesigners of healthcare services. BMJ 2015, 350, g7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, A. LinkedIn. 2025. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/an%C3%A1lisis-de-chats-whatsapp-texto-y-visualizaci%C3%B3n-datos-gonzalez/ (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2025. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/indicators-measurement-and-reporting/patient-reported-outcome-measures (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Zhu, H.; Doğan, B.E. American Joint Committee on Cancer’s Staging System for Breast Cancer, Eighth Edition: Summary for Clinicians. Eur. J. Breast Health 2021, 17, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Polo, J. Breastcancer.org. 2025. Available online: https://www.breastcancer.org/es/informe-patologico/cancer-mama-estadios?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiA_NC9BhCkARIsABSnSTavY_I1LoNX9nw-uRI9mwJjhuLyruCG9TlTY-o1FIpCFRzC_OOLTtoaArFwEALw_wcB (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- World Medical Association. WMA. 2024. [Adaptada por la 75ª Asamblea General, Helsinki, Finlandia, octubre 2024]. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Roberts, J.P.; Fisher, T.R.; Trowbridge, M.J. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthcare 2016, 4, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, G.; Herrera, R.I.M.; HCastro, K.V.; Chattu, V.K.; Sunil, T. Knowledge, Attitudes, Behavior, and Practices of Self Breast Examination in Nicaragua. Cureus 2022, 14, e21317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Rayo, R.; Pérez-Guzmán, B.; Silva-Arrechavala, R.; Muñoz-Gaitán, M.; Oporta-Hernández, W. Caracterización de pacientes con cáncer de mama atendidas en Hospital Bertha Calderón Roque, Managua-Nicaragua. Rev. Cienc. De La Salud Y Educ. Médica 2022, 3, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sihvola, S.P.; Kiwanuka, F.; Kvist, T.A. Promoting resilience among adult cancer patients: An integrative review of patient education methods. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 64, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvola, S.; Restelli, U.; Bonfanti, M.; Croce, D. Co-Design as Enabling Factor for Patient-Centred Healthcare: A Bibliometric Literature Review. Clin. Outcomes Res. CEOR 2023, 15, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsianakas, V.; Robert, G.; Maben, J.; Richardson, A.; Dale, C.; Griffin, M.; Wiseman, T. Implementing patient-centred cancer care: Using experience-based co-design to improve patient experience in breast and lung cancer services. Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 2639–2647. [Google Scholar]

- Diechmann, D.; van der Heijde, R. Harvard Business Review. 2016. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/12/how-design-thinking-turned-one-hospital-into-a-bright-and-comforting-place (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Andresen, M.L.; Potter, T.M. Improving Primary Care with Human-Centered Design and Partnership-Based Leadership. Interdiscip. J. Partnersh. Stud. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Myers, C.G.; Allen, L. Health care providers can use design thinking to improve patient experiences. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2017, 95, 222–229. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hendricks, S.; Conrad, N.; Douglas, T.S.; Mutsvangwa, T. A modified stakeholder participation assessment framework for design thinking in health innovation. Healthcare 2018, 6, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombard, Y.; Baker, G.R.; Orlando, E.; Fancott, C.; Bhatia, P.; Casalino, S.; Onate, K.; Denis, J.-L. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Triberti, S. Patient Engagement: A Consumer-Centered Model to Innovate Healthcare; De Gruyter Open: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gluyas, H. Patient-centered care: Improving healthcare outcomes. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 30, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwood, O.; Deb, R. Multidisciplinary team approach in breast cancer care: Benefits and challenges. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2020, 63 (Supplement), S105–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, K.S.; Taylor, C.; Ramirez, A.-J.; Palmieri, C.; Gunnarsson, U.; Schmoll, H.J.; Dolci, S.M.; Ghenne, C.; Metzger-Filho, O.; Skrzypski, M.; et al. Role of the multidisciplinary team in breast cancer management: Results from a large international survey involving 39 countries. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Qin, M.; Liao, B.; Wang, L.; Chang, G.; Wei, F.; Cai, S. Effectiveness of Peer Support on Quality of Life and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breast Care 2023, 18, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakunga, R.; Kinyanjui, A.; Ali, Z.; Ochieng’, E.; Gikaara, N.; Maluni, F.; Wata, D.; Kyeng’, M.; Korir, A.; Subramanian, S. Identifying Barriers and Facilitators to Breast Cancer Early Detection and Subsequent Treatment Engagement in Kenya: A Qualitative Approach. Oncologist 2019, 24, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.O.; Cazap, E.; El Saghir, N.S.; Yip, C.H.; Khaled, H.M.; Otero, I.V.; Adebamowo, C.A.; Badwe, R.A.; Harford, J.B. Optimisation of breast cancer management in low-resource and middle-resource countries: Executive summary of the Breast Health Global Initiative consensus, 2010. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Montori, V.M.; Del Mar, C. The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision making. JAMA 2014, 312, 1295–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiruvengadam, S.; Ashvetiya, T.; Stone, N.J.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Martin, S.S. Shared Decision-Making and Patient Empowerment in Preventive Cardiology. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2016, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.A.; Mohottige, D.; Sudore, R.L.; Smith, A.K.; Hanson, L.C. Tools to Promote Shared Decision Making in Serious Illness: A Systematic Review. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, D.M.; Shepherd, H.L.; Nutbeam, D.; Trevena, L.; McCaffery, K.J. Health Literacy and Shared Decision-making: Exploring the Relationship to Enable Meaningful Patient Engagement in Healthcare. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetković, J.; Nenadović, M. Depression in breast cancer patients. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 240, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casavilca-Zambrano, S.; Custodio, N.; Liendo-Picoaga, R.; Cancino-Maldonado, K.; Esenarro, L.; Montesinos, R.; Bertani, S.; Fejerman, L.; Guerchet, M.; Vidaurre, T. Depression in women with a diagnosis of breast cancer. Prevalence of symptoms of depression in Peruvian women with early breast cancer and related sociodemographic factors. Semin. Oncol. 2020, 47, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, I.; Hombrados-Mendieta, I.; Melguizo-Garín, A.; Martos-Méndez, M.J. The Importance of Social Support, Optimism and Resilience on the Quality of Life of Cancer Patients. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 833176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, J.L.; Roche, A.I.; Bronars, C.; Donovan, K.A.; Hassett, L.C.; Ehlers, S.L. Emotional distress and future healthcare utilization in oncology populations: A systematic review. Psychooncology 2024, 33, e6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Values | Number | Percentage (n = 93) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Under 30 years old | 8 | 11.6 |

| 30 to 50 years old | 34 | 36.6 | |

| 50 to 70 years old | 49 | 52.7 | |

| Over 70 years old | 2 | 2.1 | |

| Origin | Managua | 71 | 76.3 |

| Masaya | 12 | 13 | |

| Others | 10 | 10.8 | |

| Educational level | University | 82 | 88.2 |

| Secondary | 11 | 12 | |

| Years since breast cancer diagnosis | Less than a year | 19 | 20.4 |

| 1 to 5 years | 42 | 45.2 | |

| 5 to 10 years | 21 | 22.6 | |

| More than 10 years | 11 | 12 |

| Years | Cases | Early Cancer Detection | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 92 | 62 | 67 |

| 2023 | 186 | 141 | 76 |

| 2024 | 188 | 143 | 76 |

| Total | 466 | 346 | - |

| Time | Year 2022 | Year 2023 | Year 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than a min | 16% | 14% | 16 |

| From 1 to 5 min | 46% | 59% | 67 |

| From 5 to 15 min | 38% | 27% | 17 |

| Variable | Values | Numbers | Percentage (n = 93) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of support among patients in the virtual group | None | 2 | 2.1 |

| Little | 3 | 3.2 | |

| Moderate | 7 | 7.5 | |

| Very much | 81 | 87.1 | |

| Usefulness of advice among patients regarding healthcare | Very useful | 92 | 98.1 |

| Not useful | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Strengthening knowledge about breast cancer | Yes | 85 | 91.4 |

| No | 8 | 8.6 | |

| Degree of support to face difficult moments | None | 3 | 3.2 |

| Little | 15 | 16.1 | |

| Very much | 75 | 80.6 | |

| Depression diagnosis in the last 2 years | Yes | 0 | 0% |

| No | 93 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suárez, M.E.; Herrera, K.V.; Avilés, A.C.; Granados, G.; García, E.P.; Rivera, C. Patient-Centered Leadership and Co-Design of Services for Breast Cancer Program in Nicaragua. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101482

Suárez ME, Herrera KV, Avilés AC, Granados G, García EP, Rivera C. Patient-Centered Leadership and Co-Design of Services for Breast Cancer Program in Nicaragua. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101482

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuárez, María Esther, Karen Vanessa Herrera, Alma Celeste Avilés, Gonzalo Granados, Ena Patricia García, and Chepita Rivera. 2025. "Patient-Centered Leadership and Co-Design of Services for Breast Cancer Program in Nicaragua" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101482

APA StyleSuárez, M. E., Herrera, K. V., Avilés, A. C., Granados, G., García, E. P., & Rivera, C. (2025). Patient-Centered Leadership and Co-Design of Services for Breast Cancer Program in Nicaragua. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101482

_Garrett.png)