Unravelling the Association Between Trait Mindfulness and Problematic Social Media Use in Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Measures

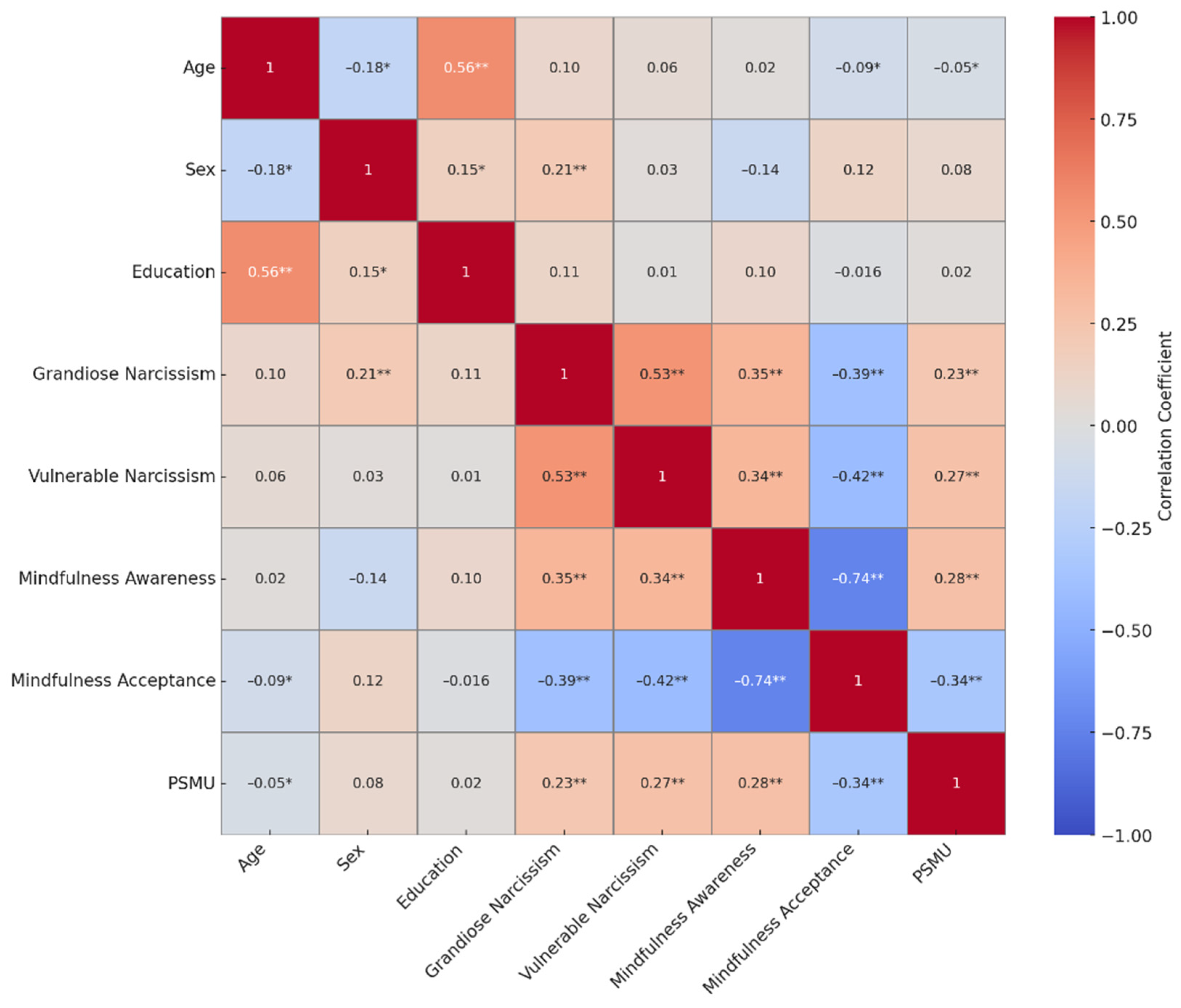

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H. Relationship Between Self-Esteem and Problematic Social Media Use Amongst Chinese College Students: A Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 679, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, P.C.-I.; Jiang, W.; Pu, G.; Chan, K.-S.; Lau, Y. Social media engagement in two governmental schemes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Macao. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Demetrovics, Z.; Elhai, J.D.; Grant, D.; Koning, I.; Rumpf, H.J.; van den Eijnden, R. Problematic social media use in childhood and adolescence. Addict. Behav. 2024, 153, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolinakou, A.; Phua, J.; Kwon, E.S. What drives addiction on social media sites? The relationships between psychological well-being states, social media addiction, brand addiction and impulse buying on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 153, 108086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.; Tynjälä, J.; Lahti, H.; Ojala, K.; Lyyra, N. Problematic social media use and health among adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancola, M.; Perazzini, M.; Bontempo, D.; Perilli, E.; D’Amico, S. Narcissism and problematic social media use: A moderated mediation analysis of fear of missing out and trait mindfulness in youth. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 8554–8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, P.; Manktelow, R.; Taylor, B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 41, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addict. Behav. 2021, 114, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.; Van Den Eijnden, R.J.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Wong, S.L.; Inchley, J.C.; Badura, P.; Stevens, G.W. Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, S89–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynadier, J.; Malouff, J.M.; Loi, N.M.; Schutte, N.S. Lower mindfulness is associated with problematic social media use: A meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 3395–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailey, S.L.; Howard, K.; Roming, S.M.; Ceballos, N.; Grimes, T. A biopsychosocial approach to understanding social media addiction. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, C.; Gini, G.; Vieno, A.; Spada, M.M. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vossen, H.G.; van den Eijnden, R.J.; Visser, I.; Koning, I.M. Parenting and problematic social media use: A systematic review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2024, 11, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.O. Social media psychology and mental health. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, S.; Noferesti, A.; Farahani, H. Investigating the Relationship Between Problematic Social Media Use and Dark Personality Traits with the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation Among Adult Instagram Users in Tehran. J. Assess. Res. Appl. Couns. 2024, 6, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Wegmann, E.; Stark, R.; Müller, A.; Wölfling, K.; Robbins, T.W.; Potenza, M.N. The I-PACE model for addictive behaviors: Update and generalization to internet-use disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 104, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Vinciguerra, M.G.; D’Amico, S. Narcissism and the risk of exercise addiction in youth: The impact of problematic social media use and fitspiration exposure. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2025, 22, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P.; Bierhoff, H.W. The Social Online Self-Regulation Theory: A framework for the psychological mechanisms underlying social media use. J. Media Psychol. 2020, 33, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Cao, B.; Sun, Q. The association between problematic internet use and social anxiety within adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1275723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, Q.; Wang, T.; Jarwar, A.H. Narcissism, perfectionism, and self-promoting behavior on social networking sites among university students in Pakistan. An. Psicol. 2024, 40, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Banchi, V. Narcissism and problematic social media use: A systematic literature review. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2020, 11, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancola, M.; Palmiero, M.; D’Amico, S. The association between Dark Triad and pro-environmental behaviours: The moderating role of trait emotional intelligence (La asociación entre la Tríada Oscura y las conductas proambientales: El papel moderador de la inteligencia emocional rasgo). PsyEcology 2023, 14, 338–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, A.; Baird, N.; Jensen, L.; Benson, A.J. Narcissism and seeing red: How perceptions of social rank conflict fuels dominance. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2023, 214, 112328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.A.; Freis, S.D.; Carroll, P.J.; Arkin, R.M. Perceived agency mediates the link between the narcissistic subtypes and self-esteem. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 90, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizan, Z.; Herlache, A.D. The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 22, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizan, Z. The narcissism spectrum model: A spectrum perspective on narcissistic personality. In Handbook Trait Narcissism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Carone, N.; Benzi, I.M.A.; Parolin, L.A.L.; Fontana, A. “I can’t miss a thing”—The contribution of defense mechanisms, grandiose narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism to fear of missing out in emerging adulthood. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2023, 214, 112333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P.; Baer, F.; Förster, J. Materialists on Facebook: The self-regulatory role of social comparisons and the objectification of Facebook friends. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; D’Amico, S.; Vinciguerra, M.G. Unveiling the dark side of eating disorders: Evidence on the role of dark triad and body uneasiness in youth. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1437510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegan, R.B.; Bland, A.R. Social media use and vulnerable narcissism: The differential roles of oversensitivity and egocentricity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, J.L.; Campbell, W.K. Narcissism and social media use: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2018, 7, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcerowska, J.M.; Sawicki, A.; Brailovskaia, J.; Zajenkowski, M. Different aspects of narcissism and social networking sites addiction in Poland and Germany: The mediating role of positive and negative reinforcement expectancies. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2023, 207, 112172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. The “Bubbles”-Study: Validation of ultra-short scales for the assessment of addictive social media use and grandiose narcissism. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 13, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Ren, S.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Song, L.; Xi, J.; Mottus, R. The longitudinal association between narcissism and problematic social networking sites use: The roles of two social comparison orientations. Addict. Behav. 2023, 145, 107786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Fioravanti, G.; Rugai, L. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissists: Who is at higher risk for social networking addiction? Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musetti, A.; Grazia, V.; Alessandra, A.; Franceschini, C.; Corsano, P.; Marino, C. Vulnerable narcissism and problematic social networking sites use: Focusing the lens on specific motivations for social networking sites use. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, J. Development and validation of the Chinese social media addiction scale. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2018, 134, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P.; Bierhoff, H.-W.; Hanke, S. Do vulnerable narcissists profit more from Facebook use than grandiose narcissists? An examination of narcissistic Facebook use in the light of self-regulation and social comparison theory. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2018, 124, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P.; Bierhoff, H.-W.; Rohmann, E. How downward and upward comparisons on Facebook influence grandiose and vulnerable narcissists’ self-esteem—A priming study. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieve, R.; March, E.; Watkinson, J. Inauthentic self-presentation on facebook as a function of vulnerable narcissism and lower self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.; Xue, J.; Chen, S. Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce burnout of college students in China? A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 880–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Xiong, W.; Liu, X.; An, J. Trait mindfulness and problematic smartphone use in Chinese early adolescents: The multiple mediating roles of negative affectivity and fear of missing out. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, E.R.; Yousaf, O.; Vitterso, A.D.; Jones, L. Dispositional mindfulness and psychological health: A systematic review. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living, 3rd ed.; Deltra Trade: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardaciotto, L.; Herbert, J.D.; Forman, E.M.; Moitra, E.; Farrow, V. The assessment of present-moment awareness and acceptance: The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment 2008, 15, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness, acceptance, and emotion regulation: Perspectives from Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, A.; Levin, M.E.; Garland, E.L.; Romanczuk-Seiferth, N. Mindfulness in treatment approaches for addiction—Underlying mechanisms and future directions. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2021, 8, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, B.; Miller, J.D.; Hoffman, B.J.; Reidy, D.E.; Zeichner, A.; Campbell, W.K. A test of two brief measures of grandiose narcissism: The Narcissistic Personality Inventory–13 and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory–16. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Ferrandes, A.; D’Amico, S. Mirror, mirror on the wall: The role of narcissism, muscle dysmorphia, and self-esteem in bodybuilders’ muscularity-oriented disordered eating. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 32697–32706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, A.; Borroni, S.; Grazioli, F.; Dornetti, L.; Marcassoli, I.; Maffei, C.; Cheek, J. Tracking the hypersensitive dimension in narcissism: Reliability and validity of the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale. Pers. Ment. Health 2009, 3, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.C.; Cardaciotto, L.; Moon, S.; Marks, D. Validation of the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale on experienced meditators and nonmeditators. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 725–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monacis, L.; De Palo, V.; Griffiths, M.D.; Sinatra, M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Liu, S.; Chen, S. The effect of trait mindfulness on social media rumination: Upward social comparison as a moderated mediator. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 931572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynadier, J.; Malouff, J.M.; Schutte, N.S.; Loi, N.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Relationships between social media addiction, social media use metacognitions, depression, anxiety, fear of missing out, loneliness, and mindfulness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Garland, E.L.; O’Brien, J.E.; Tronnier, C.; McGovern, P.; Anthony, B.; Howard, M.O. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for video game addiction in emerging adults: Preliminary findings from case reports. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 16, 928–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throuvala, M.A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Rennoldson, M.; Kuss, D.J. Mind over matter: Testing the efficacy of an online randomized controlled trial to reduce distraction from smartphone use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoensukmongkol, P.; Pandey, A. Trait mindfulness and cross-cultural sales performance: The role of perceived cultural distance. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2021, 38, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Bocchi, A.; Palmiero, M.; De Grossi, I.; Piccardi, L.; D’Amico, S. Examining cognitive determinants of planning future routine events: A pilot study in school-age Italian children (Análisis de los determinantes cognitivos de la planificación de eventos de rutina futuros: Un estudio piloto con niños italianos en edad escolar). Stud. Psychol. 2023, 44, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benucci, S.B.; Rega, V.; Boursier, V.; Casale, S.; Fioravanti, G. Impulsivity and problematic social network sites use: A meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 188, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.L.; Kwak, J.J.; Beatty-Wright, J.F. Sense of purpose and emotion regulation strategy use: A mini-review with directions for future research. J. Mood Anxiety Disord. 2025, 11, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Huang, L.; Yang, F. Social anxiety and problematic social media use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict. Behav. 2024, 153, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cingel, D.P.; Carter, M.C.; Krause, H.V. Social media and self-esteem. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Frequency (%) | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 22.16 (2.47) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 85 (47.2) | |

| Female | 95 (52.8) | |

| Education | ||

| High School | 84 (46.7) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 93 (51.7) | |

| Master’s degree | 3 (1.7) |

| B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||||

| Age | −0.17 | 0.20 | −0.07 | −0.80 | 0.42 |

| Sex | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.07 | 0.97 | 0.34 |

| Education | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.77 | 0.44 |

| R2 = 0.01 | |||||

| F(3, 176) = 0.61 | |||||

| Step 2 | |||||

| Age | −0.23 | 0.20 | −0.10 | −1.13 | 0.26 |

| Sex | 0.43 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.62 |

| Education | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.74 | 0.46 |

| Grandiose Narcissism | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.11 | 1.27 | 0.21 |

| Vulnerable Narcissism | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 2.47 | 0.01 |

| R2 = 0.09 | |||||

| F(5, 174) = 3.51 ** | |||||

| Step 3 | |||||

| Age | −0.18 | 0.20 | −0.08 | −0.91 | 0.37 |

| Sex | 1.06 | 0.87 | 0.09 | 1.22 | 0.23 |

| Education | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.77 |

| Grandiose Narcissism | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.74 |

| Vulnerable Narcissism | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 1.51 | 0.13 |

| Mindfulness Awareness | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.44 | 0.66 |

| Mindfulness Acceptance | −0.24 | 0.10 | −0.26 | −2.37 | 0.02 |

| R2 = 0.16 | |||||

| F(7, 172) = 4.50 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galli, E.; Sannino, M.; Dridi, Z.; Giancola, M. Unravelling the Association Between Trait Mindfulness and Problematic Social Media Use in Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101479

Galli E, Sannino M, Dridi Z, Giancola M. Unravelling the Association Between Trait Mindfulness and Problematic Social Media Use in Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101479

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalli, Elisa, Marta Sannino, Zidane Dridi, and Marco Giancola. 2025. "Unravelling the Association Between Trait Mindfulness and Problematic Social Media Use in Youth" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101479

APA StyleGalli, E., Sannino, M., Dridi, Z., & Giancola, M. (2025). Unravelling the Association Between Trait Mindfulness and Problematic Social Media Use in Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101479