A Scoping Review of the Current Knowledge of the Social Determinants of Health and Infectious Diseases (Specifically COVID-19, Tuberculosis, and H1N1 Influenza) in Canadian Arctic Indigenous Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

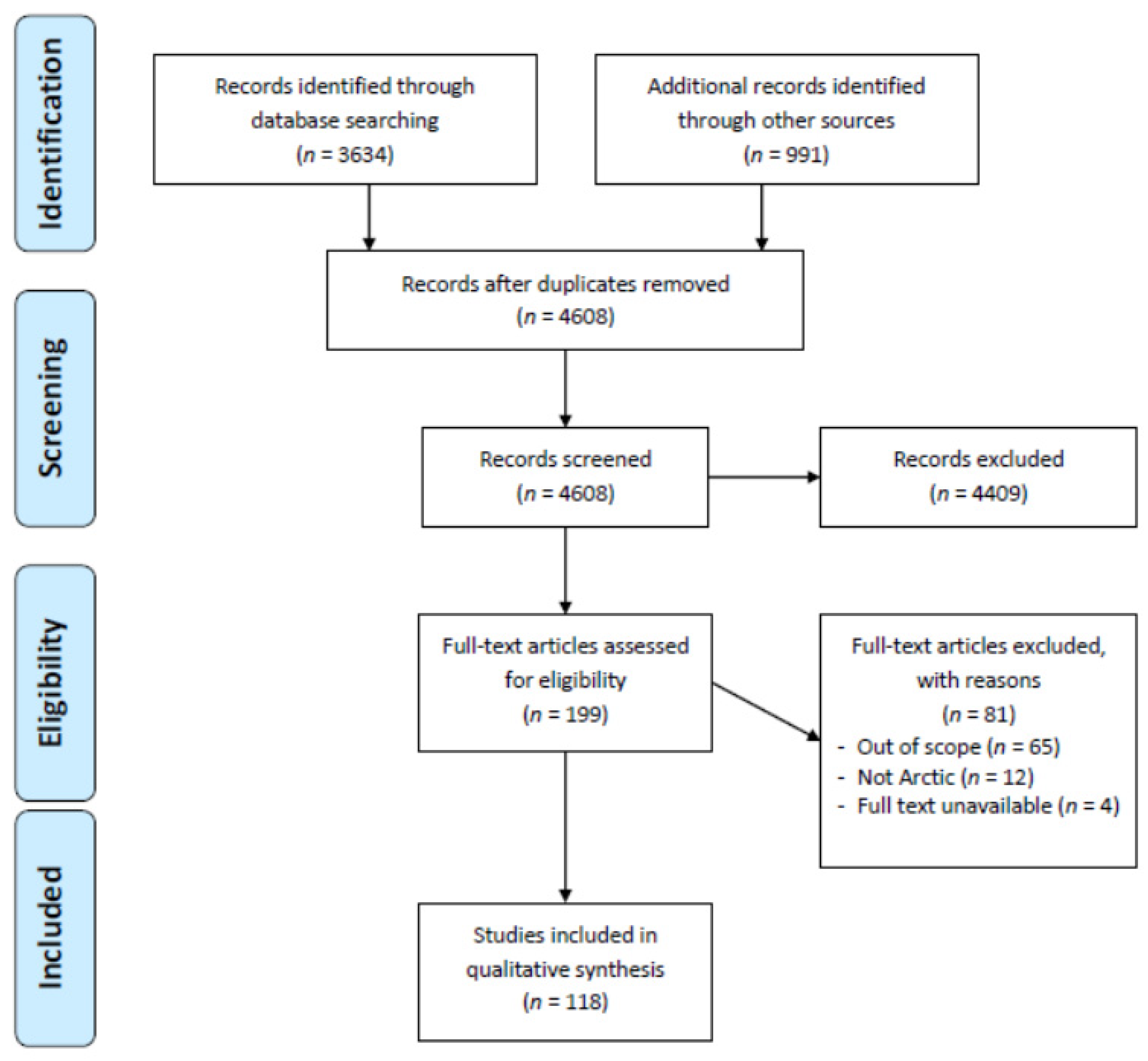

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Summarizing the Results and Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Infectious Diseases

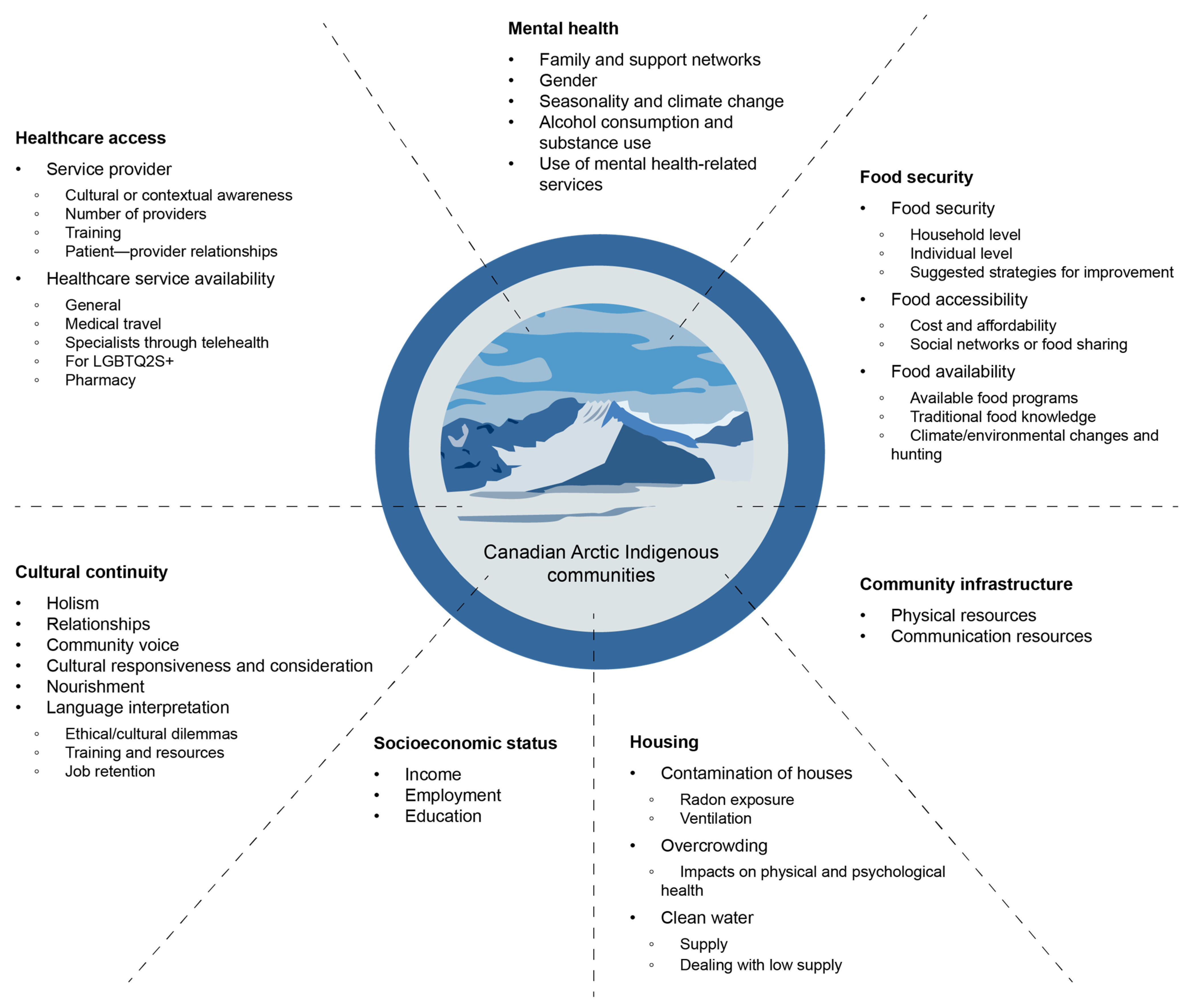

3.2. SDHs

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Results

4.2. Interpretation and Implications of Results

4.3. Shortcomings and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hansen, T. How COVID-19 Could Destroy Indigenous Communities. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200727-how-covid-19-could-destroy-indigenous-communities (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Power, T.; Wilson, D.; Best, O.; Brockie, T.; Bourque Bearskin, L.; Millender, E.; Lowe, J. COVID-19 and Indigenous Peoples: An imperative for action. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2737–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and others. The Impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous Peoples in Latin America (Abya Yala): Between Invisibility and Collective Resistance”, Project Documents; United Nations: Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, A.N.; Welford, M.; Golosov, N.; DeGroote, J.; Degai, T.; Savelyev, A. Spatiotemporal dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic in the arctic: Early data and emerging trends. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2020, 79, 1835251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leneisja Jungsberg, E.T.; Heleniak, T.; Wang, S.; Ramage, J.; Roto, J. Atlas of Population, Society and Economy in the Arctic; Nordregio: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Indigenous Population Continues to Grow and Is Much Younger than the Non-Indigenous Population, Although the Pace of Growth Has Slowed. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921a-eng.pdf?st=HxiuO8Q7 (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Young, T.K.; Bjerregaard, P. Health Transitions in Arctic Populations; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard, P.; Young, T.K.; Dewailly, E.; Ebbesson, S.O. Indigenous health in the Arctic: An overview of the circumpolar Inuit population. Scand. J. Public Health 2004, 32, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlois, A. Canada’s Arctic Tundra. Available online: https://www.hww.ca/assets/pdfs/factsheets/tundra-en.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- McNeill, W.H. Plagues and Peoples; Anchor Books/Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bonesteel, S.; Anderson, E. Canada’s Relationship with Inuit: A History of Policy and Program Development; Indian and Northern Affairs Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, S. Errors Exposed: Inuit Relocation to the High Arctic, 1953–1960. Documents on Canada’s Artic Sovereignty and Security; Centre on Foreign Policy and Federalism: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Qikiqtani Inuit Association. QTC Final Report: Achieving Saimaqatigiingniq; Inhabit Media Inc.: Iqaluit, NU, Canada, 2013; 83p. [Google Scholar]

- Vachon, J.; Gallant, V.; Siu, W. Tuberculosis in Canada, 2016. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2018, 44, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamelund, S.-E.; Sattenspiel, L.; Dimka, J. Influenza-Associated Mortality during the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic in Alaska and Labrador: A Comparison. Soc. Sci. Hist. 2013, 37, 177–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.T.; Buckeridge, D.L.; Yanyu, X.; Moghadas, S.M. The impact of geographical location of residence on disease outcomes among Canadian First Nations populations during the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic. Health Place 2014, 26, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charania, N.A.; Tsuji, L.J. The 2009 H1N1 pandemic response in remote First Nation communities of Subarctic Ontario: Barriers and improvements from a health care services perspective. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2011, 70, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.; Crawford, A. COVID-19 and the decolonization of Indigenous public health. CMAJ 2020, 192, E1098–E1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, V. The lifetime effect of residential school attendance on indigenous health status. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 2184–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, P.; Maltby, A.; Cooke, M. Residential schools and the effects on Indigenous health and well-being in Canada-a scoping review. Public Health Rev. 2017, 38, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chief Moon-Riley, K.; Copeland, J.L.; Metz, G.A.S.; Currie, C.L. The biological impacts of Indigenous residential school attendance on the next generation. SSM-Popul. Health 2019, 7, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Inuit Statistical Profile 2018; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.J. Social Determinants of Health Inequities in Indigenous Canadians Through a Life Course Approach to Colonialism and the Residential School System. Health Equity 2019, 3, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brakefield, W.S.; Olusanya, O.A.; White, B.; Shaban-Nejad, A. Social Determinants and Indicators of COVID-19 Among Marginalized Communities: A Scientific Review and Call to Action for Pandemic Response and Recovery. Disaster Med. Public 2022, 17, e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, E.M.; Szefler, S.J. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyzewski, K. Colonialism as a Broader Social Determinant of Health. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2011, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inuit Tapiirit Kanatami. Social Determinants of Inuit Health in Canada; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reading, C.; Wien, F. Health Inequalities and Social Determinants of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health; National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey Akearok, G.K.; Rana, Z. Community perspectives on COVID-19 outbreak and public health: Inuit positive protective pathways and lessons for Indigenous public health theory. Can. J. Public Health 2024, 115, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, J.G.; Clark, W.; McDonnell, L.; Nickel, N.; Dutton, R.; Kanayok, J.; Fowler-Woods, M.; Anawak, J.; Brown, N.; Voisey Clark, G.; et al. Cross-jurisdictional pandemic management: Providers speaking on the experience of Nunavut Inuit accessing services in Manitoba during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2023, 82, 2259122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Pearson, A. The systematic review: An overview. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 49–59.e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.N.; Welford, M.; Golosov, N.; DeGroote, J.; Devlin, M.; Degai, T.; Savelyev, A. The “second wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic: Regional and temporal dynamics. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2021, 80, 1925446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Petrov, A.N.; Devlin, M.; Welford, M.; Golosov, N.; DeGroote, J.; Degai, T.; Ksenofontov, S. The second year of pandemic in the Arctic: Examining spatiotemporal dynamics of the COVID-19 “Delta wave” in Arctic regions in 2021. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2022, 81, 2109562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, T.N.; Abdollahi, E.; Cipriano, L.E.; Haworth-Brockman, M.; Keynan, Y.; Sheffield, H.; Langley, J.M.; Moghadas, S.M. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions and vaccination on COVID-19 outbreaks in Nunavut, Canada: A Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, A.; Panzov, V.; Young, M.; Robinson, J.; Lee, B.; Moraes, T.; Mamdani, M.; Giles, B.L.; Jiang, D.; Bisson, D.; et al. Hospital admissions for lower respiratory tract infections among infants in the Canadian Arctic: A cohort study. CMAJ Open 2016, 4, E615–E622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charania, N.A.; Tsuji, L.J. Government bodies and their influence on the 2009 H1N1 health sector pandemic response in remote and isolated First Nation communities of sub-Arctic Ontario, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2011, 11, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charania, N.A.; Tsuji, L.J. Assessing the effectiveness and feasibility of implementing mitigation measures for an influenza pandemic in remote and isolated First Nations communities: A qualitative community-based participatory research approach. Rural Remote Health 2013, 13, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charania, N.A.; Tsuji, L.J. A community-based participatory approach and engagement process creates culturally appropriate and community informed pandemic plans after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic: Remote and isolated First Nations communities of sub-arctic Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilabuk, E.; Momoli, F.; Mallick, R.; Van Dyk, D.; Pease, C.; Zwerling, A.; Potvin, S.E.; Alvarez, G.G. Social determinants of health among residential areas with a high tuberculosis incidence in a remote Inuit community. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pease, C.; Zwerling, A.; Mallick, R.; Patterson, M.; Demaio, P.; Finn, S.; Allen, J.; Van Dyk, D.; Alvarez, G.G. The latent tuberculosis infection cascade of care in Iqaluit, Nunavut, 2012–2016. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, A.C.; Zulz, T.; Bruce, M.G.; Stenz, F.; Koch, A.; Parkinson, A.; Hennessy, T.; Cooper, M.; Newberry, C.; Randell, E.; et al. Tuberculosis in the Circumpolar Region, 2006–2012. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2018, 22, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, G.G.; Van Dyk, D.D.; Colquhoun, H.; Moreau, K.A.; Mulpuru, S.; Graham, I.D. Developing and Field Testing a Community Based Youth Initiative to Increase Tuberculosis Awareness in Remote Arctic Inuit Communities. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, G.G.; Zwerling, A.A.; Duncan, C.; Pease, C.; Van Dyk, D.; Behr, M.A.; Lee, R.S.; Mulpuru, S.; Pakhale, S.; Cameron, D.W.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis To Describe the Transmission Dynamics Among Inuit Residing in Iqaluit Nunavut Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 2187–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, V.; Chan, H.M.; Wesche, S.; Dickson, C.; Kassi, N.; Netro, L.; Williams, M. Reconciling traditional knowledge, food security, and climate change: Experience from Old Crow, YT, Canada. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2014, 8, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Ford, J.; Lardeau, M.P.; Edge, V.; Patterson, K.; Team, I.R.; Harper, S.L. Seasonal prevalence and determinants of food insecurity in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 27284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, C.; Ford, J.D.; Edge, V.L.; Shirley, J.; King, N.; Team, I.R.; Harper, S.L. Food insecurity and food consumption by season in households with children in an Arctic city: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, C.; Rosol, R.; Egeland, G.M. The prevalence of food insecurity is high and the diet quality poor in Inuit communities. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, K.; Hanning, R.M.; Desjardins, E.; Tsuji, L.J. Giving voice to food insecurity in a remote indigenous community in subarctic Ontario, Canada: Traditional ways, ways to cope, ways forward. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, K.; Hanning, R.M.; Tsuji, L.J. Prevalence and severity of household food insecurity of First Nations people living in an on-reserve, sub-Arctic community within the Mushkegowuk Territory. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, E. Sharing-based social capital associated with harvest production and wealth in the Canadian Arctic. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, L.; Pirkle, C.; Furgal, C.; Fillion, M.; Lucas, M. Psychometric validation of the household food insecurity access scale among Inuit pregnant women from Northern Quebec. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Lardeau, M.P.; Vanderbilt, W. The characteristics and experience of community food program users in arctic Canada: A case study from Iqaluit, Nunavut. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Lardeau, M.P.; Blackett, H.; Chatwood, S.; Kurszewski, D. Community food program use in Inuvik, Northwest Territories. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Lys, C.; Sokolovic, N.; Malama, K.; Mackay, K.I.; McNamee, C.; Lad, A.; Kanbari, A. Examining Pathways from Food Insecurity to Safer Sex Efficacy Among Northern and Indigenous Adolescents in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2024, 31, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeland, G.M.; Pacey, A.; Cao, Z.; Sobol, I. Food insecurity among Inuit preschoolers: Nunavut Inuit Child Health Survey, 2007–2008. CMAJ 2010, 182, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeland, G.M.; Johnson-Down, L.; Cao, Z.R.; Sheikh, N.; Weiler, H. Food insecurity and nutrition transition combine to affect nutrient intakes in Canadian arctic communities. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Germain, A.F.; Galloway, T.; Tarasuk, V. Food insecurity in Nunavut following the introduction of Nutrition North Canada. CMAJ 2019, 191, E552–E558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Berrang-Ford, L. Food security in Igloolik, Nunavut: An exploratory study. Polar Rec. 2009, 45, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.M.; Fediuk, K.; Hamilton, S.; Rostas, L.; Caughey, A.; Kuhnlein, H.; Egeland, G.; Loring, E. Food security in Nunavut, Canada: Barriers and recommendations. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2006, 65, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambden, J.; Receveur, O.; Kuhnlein, H.V. Traditional food attributes must be included in studies of food security in the Canadian Arctic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2007, 66, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambden, J.; Receveur, O.; Marshall, J.; Kuhnlein, H.V. Traditional and market food access in Arctic Canada is affected by economic factors. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2006, 65, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, K.; Hanning, R.M.; Tsuji, L.J. Barriers and supports for healthy eating and physical activity for First Nation youths in northern Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2006, 65, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, P.; Marten, M.G.; Pearce, T.; Young, A.G. Country food sharing networks, household structure, and implications for understanding food insecurity in Arctic Canada. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2016, 55, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, C.D.B.; Steegeman, P.; Voss, C.; Sonneveld, B. Food in the cold: Exploring food security and sovereignty in Whitehorse, Yukon. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2022, 81, 2025992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, J.; Castleden, H.; Furgal, C.; Sheldon, T.; Hart, C. Contemporary programs in support of traditional ways: Inuit perspectives on community freezers as a mechanism to alleviate pressures of wild food access in Nain, Nunatsiavut. Health Place 2014, 30, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelaar, N.F.; Tsuji, L.J. Impact of Euro-Canadian agrarian practices: In search of sustainable import-substitution strategies to enhance food security in subarctic Ontario, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2013, 13, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancarrow, T.L.; Chan, H.M. Observations of environmental changes and potential dietary impacts in two communities in Nunavut, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2010, 10, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesche, S.D.; Chan, H.M. Adapting to the impacts of climate change on food security among Inuit in the Western Canadian Arctic. Ecohealth 2010, 7, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, S.Z.; Walsh, D.E.; Levy, S.N.; Maksagak, B.; Milton, M.I.; Ford, J.D.; Hawley, N.L.; Dubrow, R. Determinants, effects, and coping strategies for low-yield periods of harvest: A qualitative study in two communities in Nunavut, Canada. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumier, M.C.; Ford, J.D.; Tagalik, S. The food security of Inuit women in Arviat, Nunavut: The role of socio-economic factors and climate change. Polar Rec. 2015, 51, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, L.; Lavoie, J.G.; Healy, G.; Wong, S.; Goulet, S.; Clark, W. Non-clinical determinants of Medevacs in Nunavut: Perspectives from northern health service providers and decision-makers. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2019, 78, 1571384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarlier, D.S.; Browne, A.J.; Johnson, J. The influence of geographical and social distance on nursing practice and continuity of care in a remote First Nations community. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2007, 39, 126–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, O.K.; Estey, E.A.; Rasooly, I.R.; Harris, S.; Zwarenstein, M.; Barnsley, J. Providers’ perceptions of barriers to the management of type 2 diabetes in remote Aboriginal settings. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2011, 70, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterveer, T.M.; Young, T.K. Primary health care accessibility challenges in remote indigenous communities in Canada’s North. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 29576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romain, S.J.; Kohler, J.C.; Young, K. Policy versus practice: A community-based qualitative study of the realities of pharmacy services in Nunavut, Canada. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2015, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.K.; Fedkina, N.; Chatwood, S.; Bjerregaard, P. Comparing health care workforce in circumpolar regions: Patterns, trends and challenges. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2018, 77, 1492825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T.; Horlick, S.; Cherba, M.; Cole, M.; Woodgate, R.L.; Healey Akearok, G. Perspectives of Nunavut patients and families on their cancer and end of life care experiences. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2020, 79, 1766319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, S.M.; Wiles, J.L.; Okalik, L.; Kilabuk, J.; Egeland, G.M. Living with diabetes on Baffin Island: Inuit storytellers share their experiences. Can. J. Public Health 2008, 99, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logie, C.H.; Lys, C.L.; Dias, L.; Schott, N.; Zouboules, M.R.; MacNeill, N.; Mackay, K. “Automatic assumption of your gender, sexuality and sexual practices is also discrimination”: Exploring sexual healthcare experiences and recommendations among sexually and gender diverse persons in Arctic Canada. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 1204–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, N.; Jensen, K.; MacNiven, I.; Pollock, N.; D’Hont, T.; Chatwood, S. Exploring the impact of rural health system factors on physician burnout: A mixed-methods study in Northern Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, S.L.; Nadeau, L. Experience and representations of health and social services in a community of Nunavik. Contemp. Nurse 2015, 51, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.; Pollock, N.J.; Affleck, Z.; Bain, L.; Hansen, N.L.; Robertson, K.; Chatwood, S. Patient healthcare experiences in the Northwest Territories, Canada: An analysis of news media articles. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2021, 80, 1886798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.; Topstad, D. Surgery in the western Canadian Arctic: The relative impact of family physicians with enhanced surgical skills working collaboratively with specialist surgeons. Can. J. Rural Med. 2023, 28, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.; Topstad, D.; Lee, L. Surgical Task-Sharing in the Western Canadian Arctic: A Networked Model Between Family Physicians with Enhanced Surgical Skills and Specialist Surgeons. World J. Surg. 2022, 46, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.T.; Trenholm, R. Cancer-related health behaviours and health service use among Inuit and other residents of Canada’s north. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, O.K.; Rasooly, I.R.; Naqshbandi, M.; Estey, E.A.; Esler, J.; Toth, E.; Macaulay, A.C.; Harris, S.B. Challenges to the provision of diabetes care in first nations communities: Results from a national survey of healthcare providers in Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Lys, C. The process of developing a community-based research agenda with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 28188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Lys, C.L.; Schott, N.; Dias, L.; Zouboules, M.R.; Mackay, K. ‘In the North you can’t be openly gay’: Contextualising sexual practices among sexually and gender diverse persons in Northern Canada. Glob. Public Health 2018, 13, 1865–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddy, C.; McKellips, F.; Armstrong, C.D.; Afkham, A.; Fraser-Roberts, L.; Keely, E. Improving access to specialists in remote communities: A cross-sectional study and cost analysis of the use of eConsult in Nunavut. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2017, 76, 1323493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerber, K.; Kolahdooz, F.; Otway, M.; Laboucan, M.; Jang, S.L.; Lawrence, S.; Aronyk, S.; Quinn, M.; Irlbacher-Fox, S.; Milligan, C.; et al. Opportunities for improving patient experiences among medical travellers from Canada’s far north: A mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T.K.; Tabish, T.; Young, S.K.; Healey, G. Patient transportation in Canada’s northern territories: Patterns, costs and providers’ perspectives. Rural Remote Health 2019, 19, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, M.; Barclay, K. Psychosocial costs of transferring indigenous women from their community for birth. Midwifery 2000, 16, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, H.A.; Sheffield, C.A. Nasal CPAP on paediatric air transport in the Canadian Arctic: A case series. Paediatr. Child. Health 2019, 24, e94–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jull, J.; Sheppard, A.J.; Hizaka, A.; Inuit Medical Interpreter, T.; Barton, G.; Doering, P.; Dorschner, D.; Edgecombe, N.; Ellis, M.; Graham, I.D.; et al. Experiences of Inuit in Canada who travel from remote settings for cancer care and impacts on decision making. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, I.; Jong, M.; Keays-White, D.; Turner, G. The use of remote presence for health care delivery in a northern Inuit community: A feasibility study. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 21112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.; Lavoie, J.G.; McDonnell, L.; Nickel, N.; Anawak, J.; Brown, L.; Clark, G.; Evaluardjuk-Palmer, M.; Ford, F.; Dutton, R.; et al. Trends in Inuit health services utilisation in Manitoba: Findings from the Qanuinngitsiarutiksait study. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2022, 81, 2073069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Boothroyd, L.J.; Hodgins, S. Attempted suicide among Inuit youth: Psychosocial correlates and implications for prevention. Can. J. Psychiatry 1998, 43, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, M.; Muckle, G.; Anassour-Laouan-Sidi, E.; Jacobson, S.W.; Jacobson, J.L.; Belanger, R.E. Trajectories of Alcohol Use and Binge Drinking Among Pregnant Inuit Women. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016, 51, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decaluwe, B.; Fortin, M.; Moisan, C.; Muckle, G.; Belanger, R.E. Drinking motives supporting binge drinking of Inuit adolescents. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggarty, J.M.; Cernovsky, Z.; Bedard, M.; Merskey, H. Suicidality in a sample of Arctic households. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2008, 38, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.S. Alcohol controls and violence in Nunavut: A comparison of wet and dry communities. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2011, 70, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, S.F.; Hutton, E.M. Community Psychiatry in the Canadian Arctic—Reflections From A 1-year Continuous Consultation Series in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2007, 26, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, V.; Seguin, M.; Chawky, N.; Affleck, W.; Chachamovich, E.; Turecki, G. Protective Factors in the Inuit Population of Nunavut: A Comparative Study of People Who Died by Suicide, People Who Attempted Suicide, and People Who Never Attempted Suicide. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, J.G.; Clark, W.; McDonnell, L.; Toor, J.; Nickel, N.; Anang, P.; Kusugak, M.A.; Evaluardjuk-Palmer, T.; Brown, N.; Voisey Clark, G.; et al. Inuit mental health service utilisation in Manitoba: Results from the qanuinngitsiarutiksait study. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2024, 83, 2413228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.Y.; Delgado, R.A., Jr.; Apok, C.; Baez, L.; Bjerregaard, P.; Chatwood, S.; Chipp, C.; Crawford, A.; Crosby, A.; Dillard, D.; et al. RISING SUN: Prioritized Outcomes for Suicide Prevention in the Arctic. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrasek MacDonald, J.; Cunsolo Willox, A.; Ford, J.D.; Shiwak, I.; Wood, M.; Team, I.; Rigolet Inuit Community, G. Protective factors for mental health and well-being in a changing climate: Perspectives from Inuit youth in Nunatsiavut, Labrador. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 141, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, M.J. “The weight on our shoulders is too much, and we are falling”: Suicide among Inuit male youth in Nunavut, Canada. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2013, 27, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.; George, S.; Koehn, C.; Shepard, B. Informal and formal mental health: Preliminary qualitative findings. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 21203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poliakova, N.; Riva, M.; Fletcher, C.; Desrochers-Couture, M.; Courtemanche, Y.; Moisan, C.; Fraser, S.; Pepin, C.; Belanger, R.E.; Muckle, G. Sociocultural factors in relation to mental health within the Inuit population of Nunavik. Can. J. Public Health 2024, 115, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, M.; Belanger, R.E.; Boucher, O.; Muckle, G. Temporal trends of alcohol and drug use among Inuit of Northern Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 29146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Malus, M.; Boothroyd, L.J. Suicide attempts among Inuit youth: A community survey of prevalence and risk factors. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1996, 94, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, N.J.; Mulay, S.; Valcour, J.; Jong, M. Suicide Rates in Aboriginal Communities in Labrador, Canada. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.C.; Maranzan, K.A.; Boone, M.; Vander Velde, J.; Levy, S. Caller characteristics, call contents, and types of assistance provided by caller sex and age group in a Canadian Inuit crisis line in Nunavut, 1991–2001. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2012, 42, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Lys, C.L.; Sokolovic, N.; Mackay, K.I.; Donkers, H.; Kanbari, A.; Pooyak, S.; Loppie, C. Contextual factors associated with depression among Northern and Indigenous adolescents in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Glob. Ment. Health (Camb.) 2021, 8, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affleck, W.; Oliffe, J.L.; Inukpuk, M.M.; Tempier, R.; Darroch, F.; Crawford, A.; Séguin, M.S. Suicide amongst young Inuit males: The perspectives of Inuit health and wellness workers in Nunavik. SSM-Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggarty, J.M.; Cernovsky, Z.; Husni, M.; Minor, K.; Kermeen, P.; Merskey, H. Seasonal affective disorder in an Arctic community. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2002, 105, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.; Cunsolo, A.; Pollock, N.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Wood, M.; Shiwak, I.; Flowers, C.; Harper, S.L. Temperature and place associations with Inuit mental health in the context of climate change. Environ. Res. 2021, 198, 111166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willox, A.C.; Harper, S.L.; Edge, V.L.; Landman, K.; Houle, K.; Ford, J.D.; Govt, R.I.C. The land enriches the soul: On climatic and environmental change, affect, and emotional health and well-being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Emot. Space Soc. 2013, 6, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T.; Johnson-Down, L.; Egeland, G.M. Socioeconomic and Cultural Correlates of Diet Quality in the Canadian Arctic: Results from the 2007–2008 Inuit Health Survey. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zienczuk, N.; Egeland, G.M. Association between socioeconomic status and overweight and obesity among Inuit adults: International Polar Year Inuit Health Survey, 2007–2008. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2012, 71, 18419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basham, C.A.; Karim, M.E. Multimorbidity prevalence in Canada: A comparison of Northern Territories with Provinces, 2013/14. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2019, 78, 1607703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopping, B.N.; Erber, E.; Mead, E.; Sheehy, T.; Roache, C.; Sharma, S. Socioeconomic indicators and frequency of traditional food, junk food, and fruit and vegetable consumption amongst Inuit adults in the Canadian Arctic. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 23 (Suppl. S1), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Hrenchuk, C.; Bopp, J.; Poole, N. Trajectories of women’s homelessness in Canada’s 3 northern territories. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 29778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, M.; Riva, M.; Fletcher, C. The social determinants of healthy ageing in the Canadian Arctic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2019, 78, 1630234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Lys, C.L.; Mackay, K.; MacNeill, N.; Pauchulo, A.; Yasseen, A.S., 3rd. Syndemic Factors Associated with Safer Sex Efficacy Among Northern and Indigenous Adolescents in Arctic Canada. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 26, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.K. Sociocultural and behavioural determinants of obesity among Inuit in the central Canadian Arctic. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 43, 1665–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.G.; Manion, K. Harm reduction through housing first: An assessment of the Emergency Warming Centre in Inuvik, Canada. Harm Reduct. J. 2017, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesi, T.; Gilbert, N.L.; Stocco, C.; Fugler, D.; Dales, R.E.; Guay, M.; Miller, J.D. Indoor air quality and the risk of lower respiratory tract infections in young Canadian Inuit children. CMAJ 2007, 177, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, V.; Sabo, A.; Korn, J.; MacLean, D.; Riget, F.F.; Clausen, D.S.; Cubley, J. Indoor radon survey in Whitehorse, Canada, and dose assessment. J. Radiol. Prot. 2023, 43, 011515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepin, C.; Muckle, G.; Moisan, C.; Forget-Dubois, N.; Riva, M. Household overcrowding and psychological distress among Nunavik Inuit adolescents: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2018, 77, 1541395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T.K.; Mollins, C.J. The impact of housing on health: An ecologic study from the Canadian Arctic. Arctic Med. Res. 1996, 55, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Castell, M.; Muckle, G.; Dewailly, E.; Jacobson, J.L.; Jacobson, S.W.; Ayotte, P.; Riva, M. Household crowding and food insecurity among Inuit families with school-aged children in the Canadian Arctic. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e122–e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, K.; Castleden, H.; Jamieson, R.; Furgal, C.; Ell, L. Municipal water quantities and health in Nunavut households: An exploratory case study in Coral Harbour, Nunavut, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2014, 73, 23843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, K.; Castleden, H.; Jamieson, R.; Furgal, C.; Ell, L. Water systems, sanitation, and public health risks in remote communities: Inuit resident perspectives from the Canadian Arctic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 135, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassivi, A.; Carabin, A.; Dorea, C.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Guilherme, S. Domestic access to water in a decentralized truck-to-cistern system: A case study in the Northern Village of Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik (Canada). J. Water Health 2024, 22, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatwood, S.; Paulette, F.; Baker, G.R.; Eriksen, A.M.A.; Hansen, K.L.; Eriksen, H.; Hiratsuka, V.; Lavoie, J.; Lou, W.; Mauro, I.; et al. Indigenous Values and Health Systems Stewardship in Circumpolar Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, M.J.; Idlout, L.; Minore, J.B.; Dyck, R.J.; Kirmayer, L.J. Unikkaartuit: Meanings of well-being, unhappiness, health, and community change among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.L.; Dion, M.L.; Doubleday, N.C. Cultural continuity and Inuit health in Arctic Canada. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuelsen, K.; Pearce, T.; Oakes, J.; Harper, S.L.; Ford, J.D. Sewing and Inuit women’s health in the Canadian Arctic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, C.T.R.; Giles, A.R. Community-based risk messaging in Inuvik, Northwest Territories, Canada. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, H. “Double culturedness”: The “capital” of Inuit nurses. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 21266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordyk, S.R.; Macdonald, M.E.; Brassard, P. Inuit interpreters engaged in end-of-life care in Nunavik, Northern Quebec. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2017, 76, 1291868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, V.O.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Kremers, S.P.J. Environmental and Motivational Determinants of Physical Activity among Canadian Inuit in the Arctic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, M.; Fletcher, C.; Riva, M. Aging, Health and Place from the Perspective of Elders in an Inuit Community. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2020, 35, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, V.O.; Fawehinmi, T.O.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Kremers, S.P.J. Healthy Dietary Choices and Physical Activity Participation in the Canadian Arctic: Understanding Nunavut Inuit Perspectives on the Barriers and Enablers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Hoxhaj, I.; Zaçe, D.; Ferranti, M.; Di Pietro, M.L.; Boccia, S.; Ricciardi, W. How health systems approached respiratory viral pandemics over time: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e003677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, Y.P.; Kammerer, J.S.; Silk, B.J.; Langer, A.J. Tuberculosis in Indigenous Persons—United States, 2009–2019. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 1750–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, T.; Bruden, D.; Castrodale, L.; Komatsu, K.; Erhart, L.; Thompson, D.; Bradley, K.; O’LEARY, D.; McLaughlin, J.; Landen, M. A case-control study of risk factors for death from 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1): Is American Indian racial status an independent risk factor? Epidemiol. Infect. 2016, 144, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SteelFisher, G.K.; Blendon, R.J.; Kang, M.; Ward, J.R.; Kahn, E.B.; Maddox, K.E.; Lubell, K.M.; Tucker, M.; Ben-Porath, E.N. Adoption of preventive behaviors in response to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic: A multiethnic perspective. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2015, 9, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, R.; Aguiar, A.; Pinto, M.; Furtado, I.; Tiberi, S.; Lönnroth, K.; Migliori, G.B. Different disease, same challenges: Social determinants of tuberculosis and COVID-19. Pulmonology 2021, 27, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; Department of Economic and Social Affairs Indigenous Peoples. COVID-19 and Indigenous Peoples. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/covid-19.html (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Petrov, A.N.; Dorough, D.S.; Tiwari, S.; Welford, M.; Golosov, N.; Devlin, M.; Degai, T.; Ksenofontov, S.; DeGroote, J. Indigenous health-care sovereignty defines resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2023, 401, 1478–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta-Cortijo, C.; Ford, J.D.; Galappaththi, E.K.; Namanya, D.B.; Nkwinti, N.; George, B.; Togarepi, C.; Akugre, F.A.; Arotoma-Rojas, I.; Pickering, K.; et al. Indigenous knowledge, community resilience, and health emergency preparedness. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e641–e643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services Authority. PUBLIC NOTICE: Service Update – Stanton Territorial Hospital and Medical Travel. Available online: https://www.nthssa.ca/en/newsroom/public-notice-service-update-stanton-territorial-hospital-and-medical-travel (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Government of Nunavut. COVID-19 GN Update—19 March 2020. Available online: https://gov.nu.ca/executive-and-intergovernmental-affairs/news/covid-19-gn-update-march-19-2020 (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Vose, J.M. Delay in Cancer Screening and Diagnosis During the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Is the Cost? Oncology (Williston Park) 2020, 34, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, M.D.; Brezin, A.P.; Burdon, M.; Cummings, A.B.; Evren Kemer, O.; Malyugin, B.E.; Prieto, I.; Teus, M.A.; Tognetto, D.; Tornblom, R.; et al. Early impact of COVID-19 outbreak on eye care: Insights from EUROCOVCAT group. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapum, J.; Nguyen, M.; Fredericks, S.; Lai, S.; McShane, J. “Goodbye … Through a Glass Door”: Emotional Experiences of Working in COVID-19 Acute Care Hospital Environments. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 53, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, P. Intergenerational Trauma from a Mental Health Perspective. Nativ. Soc. Work. J. 2010, 7, 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bombay, A.; Matheson, K.; Anisman, H. The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcult. Psychiatry 2014, 51, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talevi, D.; Socci, V.; Carai, M.; Carnaghi, G.; Faleri, S.; Trebbi, E.; di Bernardo, A.; Capelli, F.; Pacitti, F. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Riv. Psichiatr. 2020, 55, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagacé-Wiens, P.; Bullard, J.; Cole, R.; Van Caeseele, P. Seasonality of coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses in Canada: Implications for COVID-19. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2021, 47, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banning, J. How Indigenous people are coping with COVID-19. Cmaj 2020, 192, E787–E788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotıì ts’eeda Northwest Territories SPOR Support Unit. COVID-19 Resources for the NWT. Available online: https://nwtspor.ca/supported-projects/covid-19-resources-nwt (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Hayward, A.; Cidro, J.; Dutton, R.; Passey, K. A review of health and wellness studies involving Inuit of Manitoba and Nunavut. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2020, 79, 1779524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiris, D.; Brown, A.; Cass, A. Addressing inequities in access to quality health care for indigenous people. CMAJ 2008, 179, 985–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, S. Understanding barriers to health care: A review of disparities in health care services among indigenous populations. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2007, 66, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Thompson, S.C. An overview of cancer and beliefs about the disease in Indigenous people of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the US. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2009, 33, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, R.; Batal, M.; Johnson-Down, L.; Johnson, S.; Louie, C.; Terbasket, E.; Terbasket, P.; Wright, H.; Willows, N.; Okanagan Nation Salmon Reintroduction, I. An Indigenous food sovereignty initiative is positively associated with well-being and cultural connectedness in a survey of Syilx Okanagan adults in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahdooz, F.; Jang, S.L.; Corriveau, A.; Gotay, C.; Johnston, N.; Sharma, S. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards cancer screening in indigenous populations: A systematic review. Lancet. Oncol. 2014, 15, e504–e516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.J.; Landais, E.; Kolahdooz, F.; Sharma, S. Factors influencing the health and wellness of urban aboriginal youths in Canada: Insights of in-service professionals, care providers, and stakeholders. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, F.; Kolahdooz, F.; Sharma, S. Assessing Health Care Access and Use among Indigenous Peoples in Alberta: A Systematic Review. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2017, 28, 1286–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolahdooz, F.; Launier, K.; Nader, F.; Yi, K.J.; Baker, P.; McHugh, T.; Vallianatos, H.; Sharma, S. Canadian Indigenous Women’s Perspectives of Maternal Health and Health Care Services: A Systematic Review. Divers. Equal. Health Care 2016, 13, 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Household Food Insecurity, 2017/2018. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2020001/article/00001-eng.htm (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Polsky, J.Y.; Gilmour, H. Food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Rep. 2020, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.; Hossain, I.; Mullick, A.R.; Khan, M.H. Food Security and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2020, 8, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Elsahoryi, N.; Al-Sayyed, H.; Odeh, M.; McGrattan, A.; Hammad, F. Effect of COVID-19 on food security: A cross-sectional survey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 40, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, K.; Murray, S.; Penrose, B.; Auckland, S.; Visentin, D.; Godrich, S.; Lester, E. Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Predictors of Food Insecurity in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayasari, N.R.; Ho, D.K.N.; Lundy, D.J.; Skalny, A.V.; Tinkov, A.A.; Teng, I.C.; Wu, M.C.; Faradina, A.; Mohammed, A.Z.M.; Park, J.M.; et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Security and Diet-Related Lifestyle Behaviors: An Analytical Study of Google Trends-Based Query Volumes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Hopping, B.N.; Roache, C.; Sheehy, T. Nutrient intakes, major food sources and dietary inadequacies of Inuit adults living in three remote communities in Nunavut, Canada. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, T.; Kolahdooz, F.; Schaefer, S.E.; Douglas, D.N.; Corriveau, A.; Sharma, S. Traditional food patterns are associated with better diet quality and improved dietary adequacy in Aboriginal peoples in the Northwest Territories, Canada. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, R.; Powell-Hellyer, S.; Chan, H.M. Impacts of decline harvest of country food on nutrient intake among Inuit in Arctic Canada: Impact of climate change and possible adaptation plan. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2016, 75, 31127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakseresht, M.; Lang, R.; Rittmueller, S.; Roache, C.; Sheehy, T.; Batal, M.; Corriveau, A.; Sharma, S. Food expenditure patterns in the Canadian Arctic show cause for concern for obesity and chronic disease. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erber, E.; Beck, L.; Hopping, B.N.; Sheehy, T.; De Roose, E.; Sharma, S. Food patterns and socioeconomic indicators of food consumption amongst Inuvialuit in the Canadian Arctic. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 23, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.; Oliveira, A.M. Poverty and food insecurity may increase as the threat of COVID-19 spreads. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 3236–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, M.; Gurney, J.; Harris, R.; Cormack, D.; King, P. COVID-19: We must not forget about Indigenous health and equity. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2023, 44, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.; Akearok, G.H.; Cueva, K.; Lavoie, J.G.; Larsen, C.V.; Johannsdottir, L.; Cook, D.; Nilsson, L.M.; Rautio, A.; Timlin, U.; et al. Public health restrictions, directives, and measures in Arctic countries in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2023, 82, 2271211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Archived: Guidance on the Prioritization of Initial Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine(s). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/guidance-prioritization-initial-doses-covid-19-vaccines.html (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Young, T.K.; Broderstad, A.R.; Sumarokov, Y.A.; Bjerregaard, P. Disparities amidst plenty: A health portrait of Indigenous peoples in circumpolar regions. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2020, 79, 1805254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Further studies |

|

| Public health policies and programmes |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolahdooz, F.; Jang, S.L.; Deck, S.; Ilkiw, D.; Omoro, G.; Rautio, A.; Pirkola, S.; Møller, H.; Ferguson, G.; Evengård, B.; et al. A Scoping Review of the Current Knowledge of the Social Determinants of Health and Infectious Diseases (Specifically COVID-19, Tuberculosis, and H1N1 Influenza) in Canadian Arctic Indigenous Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010001

Kolahdooz F, Jang SL, Deck S, Ilkiw D, Omoro G, Rautio A, Pirkola S, Møller H, Ferguson G, Evengård B, et al. A Scoping Review of the Current Knowledge of the Social Determinants of Health and Infectious Diseases (Specifically COVID-19, Tuberculosis, and H1N1 Influenza) in Canadian Arctic Indigenous Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolahdooz, Fariba, Se Lim Jang, Sarah Deck, David Ilkiw, Gertrude Omoro, Arja Rautio, Sami Pirkola, Helle Møller, Gary Ferguson, Birgitta Evengård, and et al. 2025. "A Scoping Review of the Current Knowledge of the Social Determinants of Health and Infectious Diseases (Specifically COVID-19, Tuberculosis, and H1N1 Influenza) in Canadian Arctic Indigenous Communities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010001

APA StyleKolahdooz, F., Jang, S. L., Deck, S., Ilkiw, D., Omoro, G., Rautio, A., Pirkola, S., Møller, H., Ferguson, G., Evengård, B., Mantla-Look, L., DeLancey, D., Corriveau, A., Irlbacher-Fox, S., Wagg, A., Roache, C., Rittenbach, K., Conter, H. J., Falk, R., & Sharma, S. (2025). A Scoping Review of the Current Knowledge of the Social Determinants of Health and Infectious Diseases (Specifically COVID-19, Tuberculosis, and H1N1 Influenza) in Canadian Arctic Indigenous Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010001