A Scoping Review of Instruments Used in Measuring Social Support among Refugees in Resettlement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Support Measurement

1.2. Social Support among Refugees in Resettlement

1.3. Best Practices in Scale Development

1.4. Study Aims

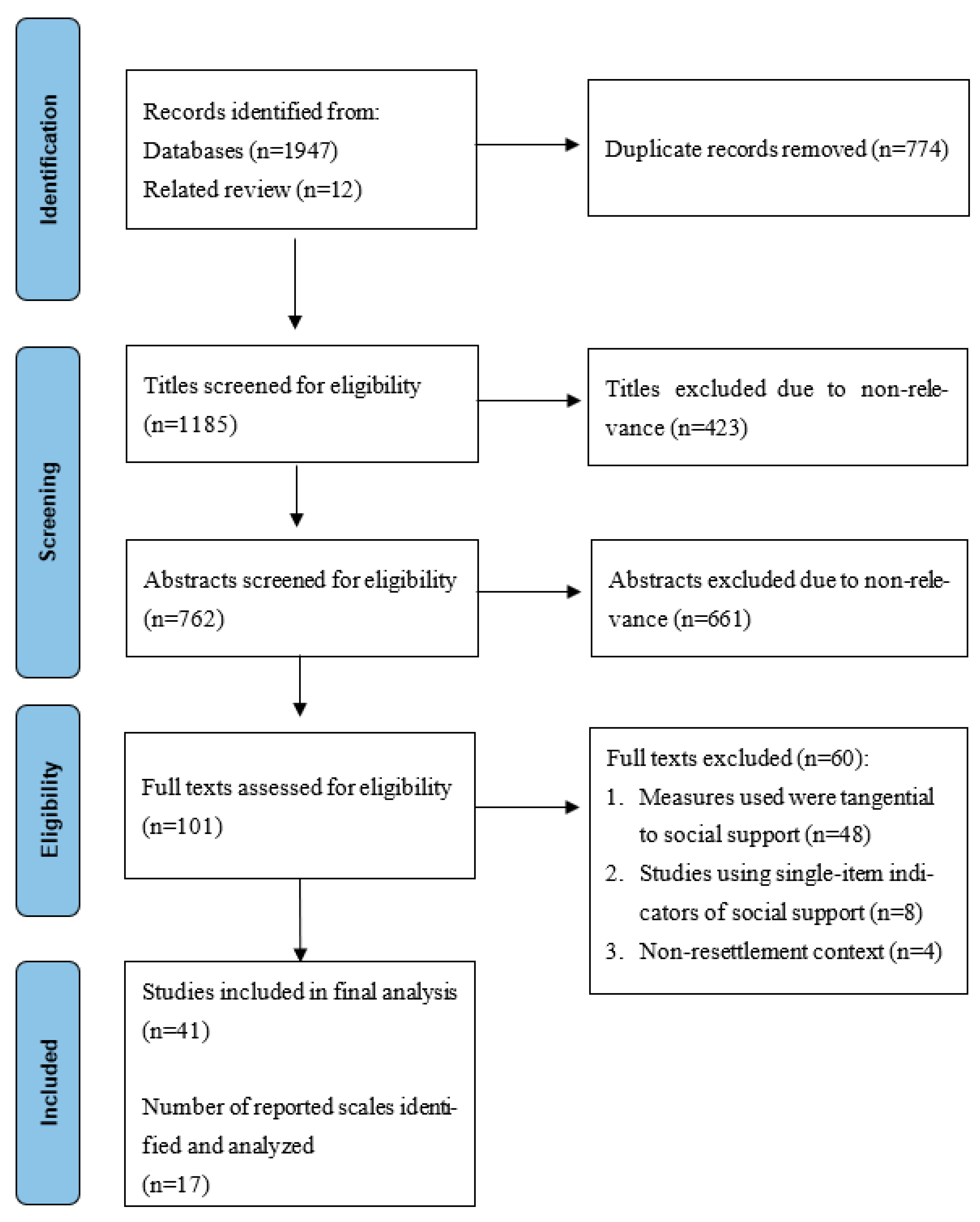

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Step 1: Formulating Research Questions

2.2. Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Step 3: Study Selection

2.4. Step 4: Charting and Analyzing Data

3. Results

3.1. Social Support Instruments Identified in the Literature

3.2. Populations and Countries of Resettlement in Which Studies Were Conducted

3.3. Domains and Formats of the Instruments

3.4. Psychometric Assessments of the Original Social Support Instruments

3.5. Adaptation of Social Support Instruments in Studies with Resettled Refugees

3.6. Assessments of Social Support Instruments Validated in Studies with Resettled Refugees

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, P.; Barclay, L.; Schmied, V. Defining Social Support in Context: A Necessary Step in Improving Research, Intervention, and Practice. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 942–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, K.; Bunn, M.; Schuster, R.C.; Boateng, G.O.; Cameli, K.; Johnson-Agbakwu, C.E. A Scoping Review of Social Support Research among Refugees in Resettlement: Implications for Conceptual and Empirical Research. J. Refug. Stud. 2022, 35, 368–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarason, I.G.; Levine, H.M.; Basham, R.B.; Sarason, B.R. Assessing Social Support: The Social Support Questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, E.; Allen, L.; Aber, J.L.; Mitchell, C.; Feinman, J.; Yoshikawa, H.; Comtois, K.A.; Golz, J.; Miller, R.L.; Ortiz-Torres, B.; et al. Development and Validation of Adolescent-Perceived Microsystem Scales: Social Support, Daily Hassles, and Involvement. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 355–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubow, E.F.; Ullman, D.G. Assessing Social Support in Elementary School Children: The Survey of Children’s Social Support. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1989, 18, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A.; Mattimore, L.K.; King, D.W.; Adams, G.A. Family Support Inventory for Workers: A New Measure of Perceived Social Support from Family Members. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procidano, M.E.; Heller, K. Measures of Perceived Social Support from Friends and from Family: Three Validation Studies. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1983, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The MOS Social Support Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Dunkel Schetter, C.; Kerney, M. The Multidimensional Nature of Received Social Support in Gay Men at Risk of HIV Infection and AIDS. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1994, 22, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çürük, G.N.; Kartin, P.T.; Şentürk, A.; Çürük, G.N.; Kartin, P.T.; Şentürk, A. A Survey of Social Support and Psychosocial Compliance in Patients with Breast Cancer. Arch. Nurs. Pract. Care 2020, 6, 013–018. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, D.L.; Mittelman, M.S.; Clay, O.J.; Madan, A.; Haley, W.E. Changes in Social Support as Mediators of the Impact of a Psychosocial Intervention for Spouse Caregivers of Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease. Psychol. Aging 2005, 20, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.D.; Collins, S.M.; Boateng, G.O.; Widen, E.M.; Natamba, B.; Achoko, W.; Acidri, D.; Young, S.L.; Martin, S.L. Pathways Linking Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Exclusive Breastfeeding among Women in Northern Uganda. Glob. Public. Health 2022, 17, 3506–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, N.; Borawski-Clark, E. Social Class Differences in Social Support Among Older Adults1. Gerontol. 1995, 35, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, B.H.; Bergen, A.E. Social Support Concepts and Measures. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, S. Social Support as a Moderator of Life Stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, J.S. Work Stress and Social Support; Addison-Wesley Series on Occupational Stress; Addison-Wesley Publishing: Melbourne, WC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Syme, S.L. Issues in the Study and Application of Social Support. Soc. Support Health 1985, 3, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Gottlieb, B.H.; Underwood, L.G. Social Relationships and Health: Challenges for Measurement and Intervention. Adv. Mind-Body Med. 2001, 17, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barrera, M. Distinctions between Social Support Concepts, Measures, and Models. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 413–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Psychological Stress and the Coping Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Transactional Theory and Research on Emotions and Coping. Eur. J. Pers. 1987, 1, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Shinar, O. Measuring Perceived and Received Social Support. In Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists; Cohen, S., Underwood, L.G., Gottlieb, B.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 86–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, D.D.; Pack, A.; Uhrig Castonguay, B.; Stewart, J.L.; Schalkoff, C.; Cherkur, S.; Schein, M.; Go, M.; Devadas, J.; Fisher, E.B. Validity of Social Support Scales Utilized among HIV-Infected and HIV-Affected Populations: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 2155–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortney, J.C.; Garcia, N.; Simpson, T.L.; Bird, E.R.; Carlo, A.D.; Rennebohm, S.; Campbell, S.B. A Systematic Review of Social Support Instruments for Measurement-Based Care in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 20056–20073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Anderson, J.; Beiser, M.; Mwakarimba, E.; Neufeld, A.; Simich, L.; Spitzer, D. Multicultural Meanings of Social Support among Immigrants and Refugees. Int. Migr. 2008, 46, 123–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, M.; Samuels, G.; Higson-Smith, C. Ambiguous Loss of Home: Syrian Refugees and the Process of Losing and Remaking Home. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2023, 4, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, N.; Schnyder, U.; Schick, M.; Nickerson, A.; Bryant, R.A. Attachment Style and Interpersonal Trauma in Refugees. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haene, L.; Grietens, H.; Verschueren, K. Adult Attachment in the Context of Refugee Traumatisation: The Impact of Organized Violence and Forced Separation on Parental States of Mind Regarding Attachment. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2010, 12, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachter, K.; Gulbas, L.E. Social Support under Siege: An Analysis of Forced Migration among Women from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 208, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidinger, E. Bridging Distance: Transnational and Local Family Ties in Refugees’ Social Support Networks. J. Refug. Stud. 2024, feae043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briozzo, E.; Vargas-Moniz, M.; Ornelas, J. Critical Insights on Social Connections in the Context of Resettlement for Refugees and Asylum Seekers. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bletscher, C.; Spiers, S. “Step by Step We Were Okay Now”: An Exploration of the Impact of Social Connectedness on the Well-Being of Congolese and Iraqi Refugee Women Resettled in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, K.; Gulbas, L.E.; Snyder, S. Connecting in Resettlement: An Examination of Social Support among Congolese Women in the United States. Qual. Soc. Work 2022, 21, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Corcoran, J.; Zahnow, R. The Resettlement Journey: Understanding the Role of Social Connectedness on Well-Being and Life Satisfaction among (Im)Migrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1993, 530, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simich, L. Negotiating Boundaries of Refugee Resettlement: A Study of Settlement Patterns and Social Support*. Can. Rev. Sociol. /Rev. Can. Sociol. 2003, 40, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrickson, M.; Brown, D.B.; Fouché, C.; Poindexter, C.C.; Scott, K. ‘Just Talking About It Opens Your Heart’: Meaning-Making among Black African Migrants and Refugees Living with HIV. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). United National High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/refugees (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Zimet, G.; Dahlem, N.; Zimet, S.; Farley, G. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.H.; Powell, L.; Blumenthal, J.; Norten, J.; Ironson, G.; Pitula, C.R.; Froelicher, E.S.; Czajkowski, S.; Youngblood, M.; Huber, M. A Short Social Support Measure for Patients Recovering from Myocardial Infarction: The ENRICHD Social Support Inventory. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2003, 23, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Russell, D. The Provisions of Social Relationships and Adaptation to Stress. Adv. Pers. Relatsh. 1987, 1, 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Doma, H.; Tran, T.; Rioseco, P.; Fisher, J. Understanding the Relationship between Social Support and Mental Health of Humanitarian Migrants Resettled in Australia. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, V. Psychological Distress and Neuroticism among Syrian Refugee Parents in Post-Resettlement Contexts. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1149–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layne, C.M.; Warren, J.S.; Hilton, S.; Lin, D.; Pašalić, A.; Fulton, J.; Pašalić, H.; Katalinski, R.; Pynoos, R.S. Measuring Adolescent Perceived Support amidst War and Disaster: The Multi-Sector Social Support Inventory. In Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, US, 2009; pp. 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, P.A.; Weinert, C. The PRQ—A Social Support Measure. Nurs. Res. 1981, 30, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norbeck, J.S.; Lindsey, A.M.; Carrieri, V.L. The Development of an Instrument to Measure Social Support. Nurs. Res. 1981, 30, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadhead, W.E.; Gehlbach, S.H.; De Gruy, F.V.; Kaplan, B.H. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire: Measurement of Social Support in Family Medicine Patients. Med. Care 1988, 16, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, J.A.; Gaviria, F.M.; Pathak, D.S. The Measurement of Social Support: The Social Support Network Inventory. Compr. Psychiatry 1983, 24, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaliano, P.P.; Russo, J.; Carr, J.E.; Maiuro, R.D.; Becker, J. The Ways of Coping Checklist: Revision and Psychometric Properties. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1985, 20, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaux, A.; Phillips, J.; Holly, L.; Thomson, B.; Williams, D.; Stewart, D. The Social Support Appraisals (SS-A) Scale: Studies of Reliability and Validity. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Mermelstein, R.; Kamarck, T.; Hoberman, H.M. Measuring the Functional Components of Social Support. In Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications; Sarason, I.G., Sarason, B.R., Eds.; NATO ASI Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T.; Marcoulides, G.A. Introduction to Psychometric Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsing, K.N. Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Among Resettled Burmese in the United States. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 4077–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Othman, N.; Hynie, M.; Bayoumi, A.M.; Oda, A.; McKenzie, K. Depression-Level Symptoms among Syrian Refugees: Findings from a Canadian Longitudinal Study. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Jacelon, C.S.; Rai, S.; Ramdam, P.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Hollon, S.D. Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEW) Intervention for Mental Health Promotion Among Resettled Bhutanese Adults in Massachusetts. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsing, K.N.; Vungkhanching, M. The Relationship between Postmigration Living Difficulties, Social Support, and Psychological Distress of Burmese Refugees in the United States. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2020, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghaziri, N.; Blaser, J.; Darwiche, J.; Suris, J.-C.; Sanchis Zozaya, J.; Marion-Veyron, R.; Spini, D.; Bodenmann, P. Protocol of a Longitudinal Study on the Specific Needs of Syrian Refugee Families in Switzerland. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2019, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Chandler, G.E.; Jacelon, C.S.; Gautam, B.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Hollon, S.D. Resilience and Anxiety or Depression among Resettled Bhutanese Adults in the United States. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2019, 65, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumley, M.; Katsikitis, M.; Statham, D. Depression, Anxiety, and Acculturative Stress Among Resettled Bhutanese Refugees in Australia. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J.R.; Hess, J.M.; Isakson, B.; LaNoue, M.; Githinji, A.; Roche, N.; Vadnais, K.; Parker, D.P. Reducing Refugee Mental Health Disparities: A Community-Based Intervention to Address Postmigration Stressors with African Adults. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, N.; Mathilde, S.; Øivind, S. Post-Migration Stressors and Subjective Well-Being in Adult Syrian Refugees Resettled in Sweden: A Gender Perspective. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 717353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Younes, J.; Strømme, E.M.; Igland, J.; Abildsnes, E.; Kumar, B.; Hasha, W.; Diaz, E. Use of Health Care Services among Syrian Refugees Migrating to Norway: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haj-Younes, J.; Strømme, E.M.; Igland, J.; Kumar, B.; Abildsnes, E.; Hasha, W.; Diaz, E. Changes in Self-Rated Health and Quality of Life among Syrian Refugees Migrating to Norway: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, A.; Cauley, P.; Saboonchi, F.; Andersen, A.; Solberg, Ø. Cohort Profile: Cohort Profile: Resettlement in Uprooted Groups Explored (REFUGE)—A Longitudinal Study of Mental Health and Integration in Adult Refugees from Syria Resettled in Norway between 2015 and 2017. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottvall, M.; Sjölund, S.; Arwidson, C.; Saboonchi, F. Health-Related Quality of Life among Syrian Refugees Resettled in Sweden. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottvall, M.; Vaez, M.; Saboonchi, F. Social Support Attenuates the Link between Torture Exposure and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Male and Female Syrian Refugees in Sweden. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2019, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.A.; Poulin, P.; Crump, K. Implementing Psychosocial Support Groups in U.S. Refugee Resettlement. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2022, 48, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.B.; Daniulaityte, R.; Bhatta, D.N. Demographic and Psychosocial Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation among Resettled Bhutanese Refugees. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 23, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Othman, N.; Lou, W. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Social Support and Coping Among Afghan Refugees in Canada. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, T.; Huber, S.; Maier, T.; Maercker, A. Differential Associations Among PTSD and Complex PTSD Symptoms and Traumatic Experiences and Postmigration Difficulties in a Culturally Diverse Refugee Sample. J. Trauma. Stress 2018, 31, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frounfelker, R.L.; Mishra, T.; Carroll, A.; Brennan, R.T.; Gautam, B.; Ali, E.A.A.; Betancourt, T.S. Past Trauma, Resettlement Stress, and Mental Health of Older Bhutanese with a Refugee Life Experience. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 2149–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.M.; Callahan, J.L.; Moyer, D.N.; Connally, M.L.; Holtz, P.M.; Janis, B.M. Nepali Bhutanese Refugees Reap Support through Community Gardening. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2017, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitschke, D.B.; Aguirre, R.T.P.; Sharma, B. Common Threads: Improving the Mental Health of Bhutanese Refugee Women Through Shared Learning. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2013, 11, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J.R.; Bybee, D.; Hess, J.M.; Amer, S.; Ndayisenga, M.; Greene, R.N.; Choe, R.; Isakson, B.; Baca, B.; Pannah, M. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Multilevel Intervention to Address Social Determinants of Refugee Mental Health. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 65, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soller, B.; Goodkind, J.R.; Greene, R.N.; Browning, C.R.; Shantzek, C. Ecological Networks and Community Attachment and Support Among Recently Resettled Refugees. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 61, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charney, M.E.; Keane, T.M. The Psychological, Psychosocial, and Physical Health Status of HIV-Positive Refugees: A Comparative Analysis. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2013, 5, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, C.D.; Birman, D. Acculturation and Psychological Adjustment of Vietnamese Refugees: An Ecological Acculturation Framework. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 56, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birman, D.; Tran, N. Psychological Distress and Adjustment of Vietnamese Refugees in the United States: Association with Pre- and Postmigration Factors. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2008, 78, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, E.J.; Birman, D. Acculturation, School Context, and School Outcomes: Adaptation of Refugee Adolescents from the Former Soviet Union. Psychol. Sch. 2005, 42, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMaster, J.W.; Broadbridge, C.L.; Lumley, M.A.; Arnetz, J.E.; Arfken, C.; Fetters, M.D.; Jamil, H.; Pole, N.; Arnetz, B.B. Acculturation and Post-Migration Psychological Symptoms among Iraqi Refugees: A Path Analysis. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2018, 88, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weine, S.M.; Raina, D.; Zhubi, M.; Delesi, M.; Huseni, D.; Feetham, S.; Kulauzovic, Y.; Mermelstein, R.; Campbell, R.T.; Rolland, J. The TAFES Multi-Family Group Intervention for Kosovar Refugees: A Feasibility Study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2003, 191, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.E.; Gagnon, A.J.; Merry, L.A.; Dennis, C.-L. Risk Factors and Health Profiles of Recent Migrant Women Who Experienced Violence Associated with Pregnancy. J. Womens Health 2012, 21, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.; Simich, L.; Beiser, M.; Makumbe, K.; Makwarimba, E.; Shizha, E. Impacts of a Social Support Intervention for Somali and Sudanese Refugees in Canada. Ethn. Inequal. Health Soc. Care 2011, 4, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsbury, D.M.; Bhatta, M.P.; Castellani, B.; Khanal, A.; Jefferis, E.; Hallam, J.S. Factors Associated with the Presence of Strong Social Supports in Bhutanese Refugee Women during Pregnancy. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, T.K.; Skar, A.-M.S.; Andersson, E.S.; Birkeland, M.S. Long-Term Mental Health in Unaccompanied Refugee Minors: Pre- and Post-Flight Predictors. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1671–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, G.O.; Sun, F.; Hodge, D.R.; Androff, D.K. Religious Coping and Acculturation Stress among Hindu Bhutanese: A Study of Newly-Resettled Refugees in the United States. Int. Soc. Work 2012, 55, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.L.; Halcon, L.; Hoffman, S.J.; Osman, N.; Mohamed, A.; Areba, E.; Savik, K.; Mathiason, M.A. Health Realization Community Coping Intervention for Somali Refugee Women. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, K.; Blackburn, P.; Barker, C. The Relationship Between Trauma, Post-Migration Problems and the Psychological Well-Being of Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2011, 57, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.J.; Stoll, K. Remittance Patterns of Southern Sudanese Refugee Men: Enacting the Global Breadwinner Role*. Fam. Relat. 2008, 57, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumathipala, A.; Murray, J. New Approach to Translating Instruments for Cross-cultural Research: A Combined Qualitative and Quantitative Approach for Translation and Consensus Generation. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2000, 9, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbillis-Kolp, S.; Yotebieng, K.; Farmer, E.; Freidman, E.; Hollifield, M. Community Participatory Translation Processes for Mental Health Screening among Refugees and Forced Migrants. Traumatology 2023, 29, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, M.; Khanna, D.; Farmer, E.; Esbrook, E.; Ellis, H.; Richard, A.; Weine, S. Rethinking Mental Healthcare for Refugees. SSM-Ment. Health 2023, 3, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunn, M.; Zolman, N.; Smith, C.P.; Khanna, D.; Hanneke, R.; Betancourt, T.S.; Weine, S. Family-Based Mental Health Interventions for Refugees across the Migration Continuum: A Systematic Review. SSM-Ment. Health 2022, 2, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Instrument | # Studies |

|---|---|

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; [41]) | 8 |

| ENRICHD Social Support Instrument (ESSI; [42]) | 7 |

| Social Provisions Scale (SPS; [43]) | 4 |

| Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS SSS; [8]) | 3 |

| Multisector Social Support Inventory (MSSI; [46]) | 3 |

| Social Support Microsystems Scales (SSMS; [4]) | 3 |

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation Checklist (ISEL; [17]) | 2 |

| Personal Resource Questionnaire ([47]) | 2 |

| Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (NSSQ; [48]) | 1 |

| Duke–UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (FSSQ; [49]) | 1 |

| Social Support Network Inventory ([50]) | 1 |

| Refugee Social Support Inventory (RSSI; [45]) | 1 |

| Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA) Social Support Scale (BNLA; [44]) | 1 |

| Seeking social support subscale from the Ways of Coping Questionnaire ([51]) | 1 |

| Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ6; [3]) | 1 |

| Social Support Appraisal Scale ([52]) | 1 |

| Perceived Social Support Scale—Friend Version (PSS-Fr; [7]) | 1 |

| Instrument | Original # Items | Final # Items | Domains (# Subscales, Description) | Perceived/Received | Sources of Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; [41]) | 24 | 12 | 3, by source | Perceived | Family, friends, and significant other |

| ENRICHD Social Support Instrument (ESSI; [42]) | 7 | 7 | None specified | Perceived | 1 item asks if currently married or living with a partner/spouse |

| Social Provisions Scale [43] | 12 | 24 | 6, attachment, social integration, reassurance of worth, reliable alliance, guidance, opportunity for nurturance | Perceived | None specified |

| Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS SSS; [8]) | 50 | 19 | 5, emotional, informational, affection, tangible, positive interaction | Perceived | None specified |

| Multisector Social Support Inventory (MSSI; [46]) | 15 | 11 | 4, by source | Perceived | Nuclear family, extended family, peer support, adult mentor support |

| Social Support Microsystems Scales [4] | 28 | 21 | 3, support/cohesion, daily hassles, involvement | Perceived | Family, peer, school, neighborhood context |

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation Checklist (ISEL-12 items; [53]) | 20 | 12 | 3, appraisal, belonging, tangible | Perceived | Close confidant |

| Personal Resource Questionnaire [47] | 25 | 25 | 5, intimacy, social integration, nurturance, worth, assistance | Perceived | None specified (specified in part 2) |

| Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (NSSQ; [48]) | 9 | 9 | 6, affect, affirmation, aid short term/long term, duration, frequency of contact, recent loss | Perceived and Received | Network members |

| Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (FSSQ; [49]) | 14 | 8 | 2, affective and confidant support | Perceived | Confidant |

| Social Support Network Inventory [50] | 20 | 11 | 5, availability, practical help, reciprocity, emotional, event-related | Perceived and Received | None specified |

| Refugee Social Support Inventory (RSSI; [45]) | 24 | 24 | 5, informational and instrumental support from institutions and instrumental, informational, and emotional support from family | Received | Family/relatives, institutions |

| Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA) Social Support Scale [44] | 10 | 10 | 2, emotional/instrumental, informational | Received | National or ethnic community, religious community, community groups |

| Seeking social support subscale from the Ways of Coping Questionnaire [51] | 6 | 6 | None specified | Received (sought) | Relative/friend, professional help |

| Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ6; [3]) | 27 | 27, 6 | 3, appraisal, belonging, tangible | Perceived (satisfaction) | None specified |

| Social Support Appraisal Scale [52] | 23 | 23 | 2, adequacy, satisfaction | Perceived | Friends and family relations |

| Perceived Social Support Scale—Friend Version (PSS-Fr; [7]) | 20 | 20 | 2, perceived social support (from friends) | Perceived | Friends |

| Reported Tests of Validity | Reported Tests of Reliability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Sample | Criterion Concurrent | Criterion Predictive | Convergent | Discriminant or Divergent | Comparison between Known Groups | Internal Consistency | Test-Retest Reliability |

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; [41]) | 275 undergraduate students (136 female, 139 male; 17–22 years old) | Not reported | Depression, anxiety | Not reported | Depression and anxiety | Gender differences | α = 0.91, 0.87, 0.85 (SO, family, friends); composite: 0.88 | r = 0.72, r = 0.85, 0.75; composite: 0.85 |

| ENRICHD Social Support Instrument (ESSI; [42]) | 196 patients after myocardial infarction (121 male, 74 female, 67% White) | Perceived social support | Mortality in cardiovascular patients | Inventory of socially supportive behaviors | Social network questionnaire | Gender, minority status | α = 0.86 | Not reported |

| Social Provisions Scale [43] | 1792 (1183 university students, 303 teachers, 306 nurses) | Not reported | Loneliness, social integration, satisfaction with friends, depression, physical health | Satisfaction with support, attitude towards support, # of supportive persons, # of helping behaviors | Social desirability, depression, extraversion, neuroticism | Sex, age | α = 0.65–0.76; composite: 0.915 | Multiple studies reported reliability analyses |

| Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS SSS; [8]) | 2987 patients (39% male, 80% White, aged 18–98) | Not reported | Loneliness, emotional ties, physical functioning and pain intensity | Loneliness and family functioning | Physical and mental health status | Not reported | Emotional: α = 0.96; tangible α = 0.92; positive α = 0.94; affection α = 0.91; composite: 0.97 | r = 0.72; tangible r = 0.74; positive r = 0.72; affection r = 0.76; emotional composite: 0.78 |

| Multisector Social Support Inventory (MSSI; [46]) | 618 Sarajevo secondary school students (30% male, 63% female) | Perceived social support | Depression | Provision of social relations scale | Anxiety, somatic distress, grief, post-traumatic stress | Not reported | α = 0.80–0.93 | r = 0.59–0.81 |

| Social Support Microsystems Scales [4] | 988 youth (59% female, 26% Black, 26% White, 37% Latinos; low SES) | Not reported | Sexual activity | Not reported | Not reported | Gender, ethnicity | α = 0.74–0.81 | r = 0.48, r = 0.40, and r = 0.35 over 10 months |

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation Checklist (ISEL-12 items; [53]) | Multiple samples (mostly college students) | Not reported | Psychological symptomatology—depression scale; physical symptomatology | Inventory of socially supportive behaviors; emotional support subscales; Rosenberg self-esteem scale | Social desirability; social anxiety | Not reported | α = 0.77–0.86; composite: 0.88–0.90 | r = 0.82–0.87 over 6 weeks to six months; 6 months—0.45–0.72 |

| Personal Resource Questionnaire [47] | 149 white middle-class spouses of individuals with multiple sclerosis | Not reported | Marital adjustment and family functioning | Not reported | Self-help ideology | Not reported | α = 0.89 | r = 0.61–0.77 |

| Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (NSSQ; [48]) | 135 graduate and undergraduate nursing students (128 female, 7 male) | Not reported | Psychiatric symptomatology, life stress | Social support questionnaire (Cohen/Lazarus) | Not reported | Age, educational level, ethnic background | α = 0.95–0.98 | r = 0.85–0.92; r = 0.88–0.96 |

| Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (FSSQ; [49]) | 401 patients (28% Black, 72% White, 78% female, 22% male, 18+ years old) | Not reported | Physical function, emotional function, and symptom status | Social contacts and social activities questionnaire | Not reported | Sex, marital status, age, race, employment status, education, SES, and living situation | α = 0.52–0.73 | r = 0.66 over 13.1 days, range of 6 to 30 days |

| Social Support Network Inventory [50] | 207 nonpatients (100 students, 74 from an urban community, 32 members of a religious commune) | Not reported | Unipolar depression, social adjustment scale, Hamilton depression rating scale | Unipolar patient–clinician ratings | Not reported | Network of support, age, sex, and SES | Kuder–Richardson-20: α = 0.821, 0.76–0.91 | r = 0.87, over two weeks |

| Seeking social support subscale from the Ways of Coping Questionnaire [51] | 83 psychiatric outpatients, 62 spouses of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, 425 medical students | Not reported | Appraisal, anxiety, depression, and distress | Not reported | Not reported | Gender | 0.75—medical students, 0.79—spouse of patient, 0.81—psychiatric outpatients | Not reported |

| Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ6; [3]) | 182 undergraduate students (108 female, 74 male) | Not reported | Anxiety, depression, hostility, social competence, loneliness | Inventory of socially supportive behaviors, social network list, family environment | Not reported | Not reported | α = 0.75, α = 0.79 | r = 0.44, 0.39 |

| Social Support Appraisal Scale [52] | 5 university student samples (N = 517); 5 community samples (N = 462) | Not reported | Psychological distress, CES-depression scale, loneliness, negative affect | Social support questionnaire; provision of social relations scale; revised Kaplan scale; network orientation scale | Reported satisfaction with number of current friends; satisfaction with the quality of current friends; feeling different from friends | Not reported | α = 0.90, α = 80, α = 0.84 | Multiple studies reported reliability analyses |

| Perceived Social Support Scale—Friend Version (PSS-Fr; [7]) | Study 1: 222 undergraduate students; Study 2: 105 undergraduate students | Not reported | Life stress, symptomatology, depression, psychasthenia, schizophrenia | Social desirability; social network | Not reported | Positive and negative self-statement groups | α = 0.88, α = 0.90 | r = 0.83 over 1 month |

| Instrument | Study Citation | Population and Resettlement Country | Sample | Translation | Tests of Validity | Tests of Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; [41]) | [55] | Burmese refugees in the U.S. | 242 adults (18+); 53.3% male | English into Chin-Burmese, two bilingual translators, translated, back-translated | Construct validity, concurrent/predictive validity | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96 friends, 0.94 family, 0.96 significant other |

| [56] | Syrian refugees in Canada | 1924 adults (18+); 48.8% males; 51.2% females | Arabic translation and back-translation by two bilingual Syrian Canadians | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87 | |

| [57] | Bhutanese refugees in the U.S. | 44: adults (18+); 68.1% female | Back-translation by one bilingual Nepali and two bilingual Bhutanese | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92 | |

| [58] | Chin-Burmese refugees in the U.S. | 242: adults (18+) 53% male, 79% female | Back-translation by bilingual Chin-Burmese translators | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94 | |

| [59] | Syrian refugees and asylum seekers in Switzerland | 15: families (8+) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| [60] | Bhutanese refugees in the U.S. | 225 adults (18+), 113 male, 112 female | Not reported | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92 | |

| [61] | Bhutanese refugees in Australia | 148 adults (18+), 51.4% male, 48.6 female | Nepali nationally accredited translator and bilingual translators | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80–0.93 | |

| [62] | Refugees in the U.S. from the Great Lakes region of Africa | 36 adults (18+), 19 female, 17 male | Oral translations | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82–0.94 | |

| ENRICHD Social Support Instrument (ESSI; [42]) | [63] | Syrian refugees in Sweden | 1215 adults (18+); 475 male, 250 female | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| [64] | Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Norway | 353 adults (18+); 181 female, 171 male | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| [65] | Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Norway | 353 adults (18+); 181 female, 171 male | 2 independent forward translations, reconciliation of forward translations, back-translation, harmonization | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85 | |

| [66] | Syrian refugees in Norway | 902 adults (18+); 35.5% female, 64.5% male | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| [67] | Syrian refugees in Sweden | 1215 adults (18+) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| [68] | Syrian refugees in Norway | 1215 adults (18+); 475 male, 250 female | Not reported | Construct validity, comparison between known groups | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.906 | |

| Social Provisions Scale [43] | [69] | Refugees in the U.S. from east and central Africa | 97 adults (18+) | Not reported | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.915 |

| [70] | Bhutanese refugees in the U.S. | 200 adults (18+) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| [71] | Afghan refugees in the U.S. | 49 adults (18+), 41% male, 59% female | Not reported | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96 | |

| [72] | Refugees from multiple countries of origin in Switzerland | 94 adults (18+), 85.1% male | Translated by native speakers or trained translators and back-translated in blind written form | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77 | |

| Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS SSS; [8]) | [73] | Bhutanese refugees in the U.S. and Canada | 190 older adults (50+) | Forward- and back-translated from English to Nepali by Bhutanese team members | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89 |

| [74] | Bhutanese in the U.S. | 50 adults (18+), 62% female | Forward and back-translation into Nepali | Not reported | Not reported | |

| [75] | Bhutanese refugees in the U.S. | 65 adults (18+), all female | Translated to Nepali by a professional translation service | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Multisector Social Support Inventory (MSSI; [46]) | [76] | Refugees in the U.S. from Afghanistan, Great Lakes region in Africa, Iraq, Syria | 290 adults (18+); 52% female | Translated and back-translated from English into Arabic, Dari, French, Kiswahili, and Pashto | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85–0.89 family, 0.91–0.93 ethnic community, 0.88–0.90 non-ethnic community |

| [77] | Refugees in the U.S. from Afghanistan, Great Lakes region in Africa, Iraq, and Syria | 178 adults (18+), 46.6% male | Not reported | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.905 | |

| [78] | Refugees in the U.S. from Burma, Cameroon, Liberia, Uganda | 84 HIV-positive adults (18+), 26 refugees | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Social Support Microsystems Scales [4] | [79] | Vietnamese refugees in the U.S. | 203 adults (18+) | Translated into Vietnamese and back-translated into English | Not reported | Not reported |

| [80] | Vietnamese refugees in the U.S. | 212 adults (18+), 103 females and 108 males | Translated into Vietnamese and back-translated by a different set of translators | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86 spouse, 0.83 other family, 0.75 Vietnamese friends, 0.79 American friends | |

| [81] | Refugees from the former Soviet Union in the U.S. | 110 adolescents | Not reported | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76 | |

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation Checklist (ISEL-12 items; [53]) | [82] | Iraqi migrants and refugees in the U.S. | 298 newly arrived, average age: 33.4 years | Translated by an Arabic bilingual psychiatrist and back-translated to English by a separate language expert | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89 |

| [83] | Kosovar refugees in the U.S. | 61 adults (18+), 38 male, 48 female | Not reported | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.67 | |

| Personal Resource Questionnaire [47] | [84] | Pregnant asylum seekers, refugees, and non-refugee immigrants in Canada | 774 adults (18+), all female | Translated and back-translated into 13 languages and pretested with monolingual individuals to assess the clarity of the questions in each language | Not reported | Not reported |

| [85] | Somali and South Sudanese refugees in Canada | 58 adults (18+), 31 male, 27 female | Translated into Arabic, Sudanese, and Somali | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (NSSQ; [48]) | [86] | Bhutanese refugee in the U.S. | 45 adults (18+), all female | Written at a 5.5-grade English reading level then translated to Nepali; back-translated by Nepali-speaking staff | Not reported | Not reported |

| Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (FSSQ; [49]) | [87] | Unaccompanied refugee minors in Norway | 95 adolescents (<16), 76 male, 19 female | Not reported | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86 |

| Social Support Network Inventory [50] | [86] | Bhutanese refugees in the U.S. | 45 adults (18+), all women | Translated and back-translated | Not reported | Not reported |

| [88] | Bhutanese in the U.S. | 112 adults | Translated into Nepali by a Bhutanese professional interpreter and back-translated by another community leader | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77 | |

| Refugee Social Support Inventory (RSSI; [45]) | [45] | Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan | 1000 parents (456 fathers, 544 mothers, 25–67 years old) | Original scale created for refugees presumably in Arabic, no report on translation processes | Content, construct, and predictive validity | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.98 |

| Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA) Social Support Scale [44] | [44] | Humanitarian migrants in Australia from Africa, Middle East, southeast, central, and southern Asia | 2264 adults (18+); 55.2% men, 44.8% women | Items were translated into multiple languages (e.g., Arabic, Persian, Dari) in the original surveys | Construct validity | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80 |

| Seeking social support in Ways of Coping [51] | [89] | Somali refugees in the U.S. | 65 women | Translated and back-translated by skilled Somali study staff and external readers. | Not reported | Not reported |

| Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ6; [3]) | [90] | Refugees/asylum seekers in the U.S. from Middle East, Africa, Europe, Asia, and South America | 48 adults (18+), 27 women, 20 men | No written translations | Not reported | Not reported |

| Social Support Appraisal Scale [52] | [91] | South Sudanese refugees in the U.S. | 172 adults (18+), all men | Translated into Arabic by a Sudanese professional and reviewed for accuracy | Not reported | Not reported |

| Perceived Social Support Scale—Friend Version (PSS-Fr; [7]) | [7] | Refugees from the former Soviet Union in the U.S. | 226 adolescents | Not reported | Not reported | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.67 |

| CB-MSPSS [55] | ESSI [42] | BNLA Social Support Scale [44] | RSSI [45] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensionality | Multidimensional

| Unidimensional scale of perceived support (seven items) | Multidimensional

| Multidimensional

|

| Original sample | College students [41] | Patients after myocardial infarction [42] | Humanitarian migrants in Australia from Africa, Middle East, southeast/central/south Asia (items identified deductively in a secondary analysis) | Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan (deductive and inductive approaches to item identification) |

| Validation sample | Chin-Burmese refugees in U.S. | Syrian refuges in Sweden | ||

| Assessments of validity | Indications of face validity, construct validity, concurrent validity | Indications of predictive validity, discriminant validity | Indications of construct validity, predictive validity, discriminant validity | Indications of face validity, content validity, construct validity, predictive validity |

| Assessments of reliability | Excellent internal consistency | Excellent internal consistency | Good to excellent internal consistency by subscale | Excellent internal consistency (reported on all items) |

| Sample items | My friends really try to help me; I obtain the emotional help and support I need from my family; I have a special person who is a real source of comfort to me. | Is there someone available to whom you can count on to listen to you when you need to talk? Is there someone available to you to give you good advice about a problem? Is there someone available to help with daily chores? | Given support/comfort from national or ethnic community; know how to look for job; know how to use public transport | Did anyone from your family or relatives give you a place to stay? Did anyone from your family or your relatives express interest and concern in your well-being or psychological condition? Did anyone from the concerned institutions help you to secure clothing? |

| Response options | Very strongly disagree; strongly disagree; mildly disagree; neutral; mildly agree; strongly agree; very strongly agree | None of the time; a little of the time; some of the time; most of the time; all of the time | Emotional/instrumental support: no, sometimes, yes; informational support: would not know at all, would know a little, would know fairly well, would know very well | Never; rarely; sometimes; most of the time |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boateng, G.O.; Wachter, K.; Schuster, R.C.; Burgess, T.L.; Bunn, M. A Scoping Review of Instruments Used in Measuring Social Support among Refugees in Resettlement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060805

Boateng GO, Wachter K, Schuster RC, Burgess TL, Bunn M. A Scoping Review of Instruments Used in Measuring Social Support among Refugees in Resettlement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(6):805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060805

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoateng, Godfred O., Karin Wachter, Roseanne C. Schuster, Tanya L. Burgess, and Mary Bunn. 2024. "A Scoping Review of Instruments Used in Measuring Social Support among Refugees in Resettlement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 6: 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060805

APA StyleBoateng, G. O., Wachter, K., Schuster, R. C., Burgess, T. L., & Bunn, M. (2024). A Scoping Review of Instruments Used in Measuring Social Support among Refugees in Resettlement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(6), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060805