Intersectional Mentorship in Academic Medicine: A Conceptual Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Limitations of the “Mutual Marginality” Approach to Mentoring

3. Intersectionality as a Framework for Mentoring

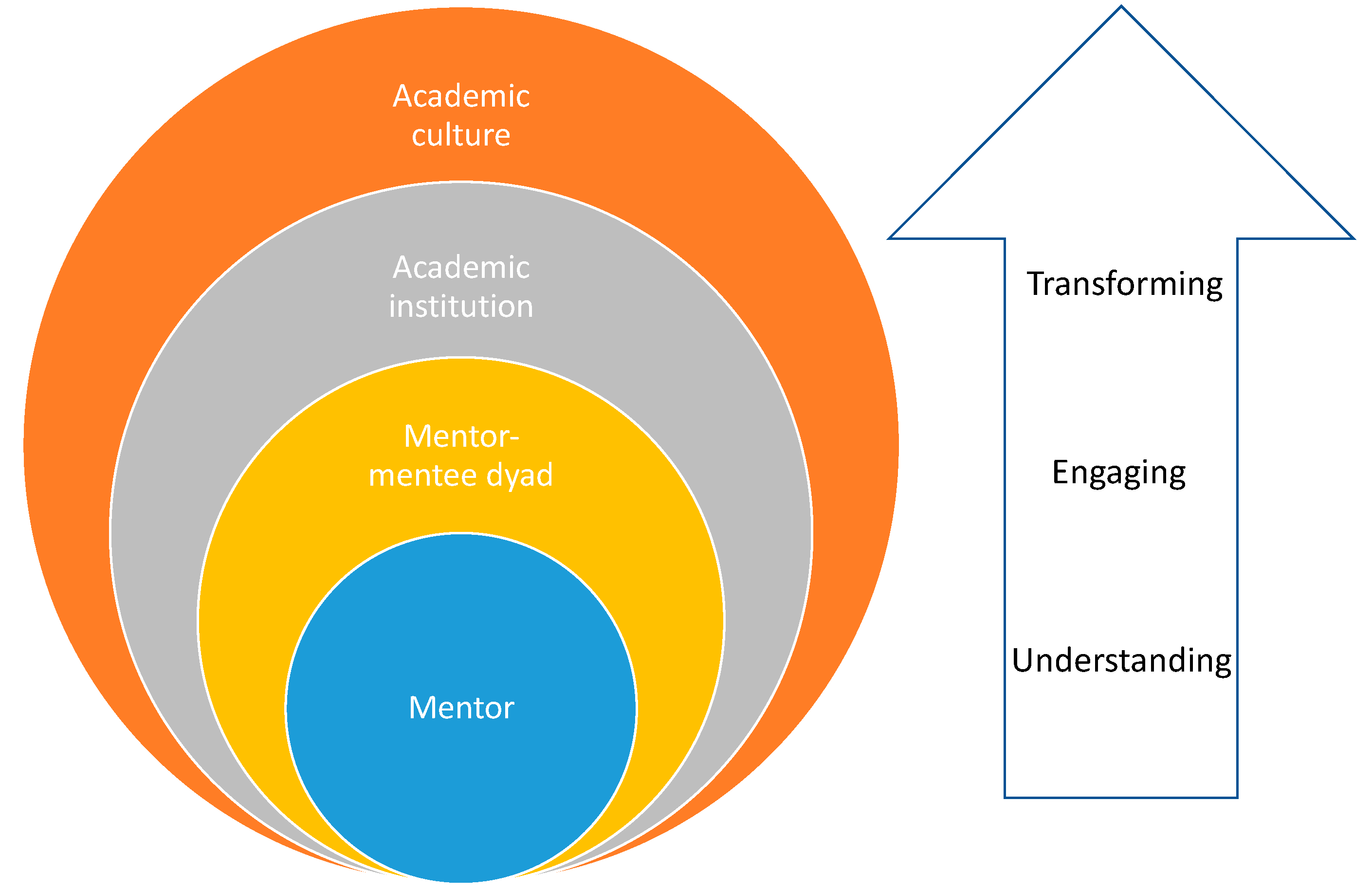

4. Understanding Intersectional Dynamics of Social Power in the Mentoring Relationship

5. Engaging with Intersectional Dynamics of Power in the Mentoring Relationship

6. Transforming Intersectional Dynamics of Power in the Mentoring Relationship and Beyond

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cashman, S.B.; Adeky, S.; Allen, A.J.; Corburn, J.; Israel, B.A.; Montaño, J.; Rafelito, A.; Rhodes, S.D.; Swanston, S.; Wallerstein, N.; et al. The Power and the Promise: Working with Communities to Analyze Data, Interpret Findings, and Get to Outcomes. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Medical Colleges. A Healthier Future for All: The AAMC Strategic Plan. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/about-us/strategic-plan/healthier-future-all-aamc-strategic-plan (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Jaakkola, E. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of California San Francisco. Faculty Mentoring Program. Available online: https://facultyacademicaffairs.ucsf.edu/faculty-life/mentoring (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Kalet, A.; Libby, A.M.; Jagsi, R.; Brady, K.; Chavis-Keeling, D.; Pillinger, M.H.; Daumit, G.L.; Drake, A.F.; Drake, W.P.; Fraser, V.; et al. Mentoring Underrepresented Minority Physician-Scientists to Success. Acad. Med. 2022, 97, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avakame, E.F.; October, T.W.; Dixon, G.L. Antiracism in Academic Medicine: Fixing the Leak in the Pipeline of Black Physicians. ATS Sch. 2021, 2, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, S.D. Writing the Conceptual Article: A Practical Guide. Digit. J. 2022, 11, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, Z.; Biskup, E.; Silet, K.; Garbutt, J.M.; Kroenke, K.; Feldman, M.D.; McGee, J.R.; Fleming, M.; Pincus, H.A. Deriving Competencies for Mentors of Clinical and Translational Scholars. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2012, 5, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.S.; Ramanan, R.A.; Feldman, M.D. Defining the Ideal Qualities of Mentorship: A Qualitative Analysis of the Characteristics of Outstanding Mentors. Am. J. Med. 2011, 124, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransdell, L.B.; Lane, T.S.; Schwartz, A.L.; Wayment, H.A.; Baldwin, J.A. Mentoring New and Early-Stage Investigators and Underrepresented Minority Faculty for Research Success in Health-Related Fields: An Integrative Literature Review (2010–2020). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.R. Pursuing Personal Passion: Learner-Centered Research Mentoring. Fam. Med. 2018, 50, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, C.; Piggott, C.; Davis, A.; Hall, M.N.; Goodell, K.; Joo, P.; South-Paul, J.E. Leadership Pathways in Academic Family Medicine: Focus on Underrepresented Minorities and Women. Fam. Med. 2020, 52, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.G.; Sherman, A.E.; Kiet, T.K.; Kapp, D.S.; Osann, K.; Chen, L.-M.; O’Sullivan, P.S.; Chan, J.K. Characteristics of success in mentoring and research productivity—A case control study of academic centers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 125, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Introduction to Mentoring: A Guide for Mentors and Mentees. Available online: https://www.apa.org/education/grad/mentoring (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Dixon, G.; Kind, T.; Wright, J.; Stewart, N.; Sims, A.; Barber, A. Factors That Influence the Choice of Academic Pediatrics by Underrepresented Minorities. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20182759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, B.M.; Calles-Escandon, J.; Hairston, K.G.; Langdon, S.E.; Latham-Sadler, B.A.; Bell, R.A. Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical centers: A systematic review of the literature. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2013, 88, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.A. The truth about mentoring minorities: Race matters. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 79, 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, K.L.; Simoni, J.M.; Evans-Campbell, T.; Udell, W.; Johnson-Jennings, M.; Pearson, C.R.; MacDonald, M.M.; Duran, B. Mentoring the Mentors of Underrepresented Racial/Ethnic Minorities Who are Conducting HIV Research: Beyond Cultural Competency. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.E.; Dimant, O.E.; Novick, R.; Adegbola, A.; Blackstock, U.; Drake, C.B.; Patenaude, M.E.; Ravenell, J.E.; Radix, A.; Greene, R.E. Gendered Expectations: Strategies for Navigating Structural Challenges in Support of Transgender and Non-Binary Trainees in Academic Medicine. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, P. Structural sexism and health in the United States: A new perspective on health inequality and the gender system. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 84, 486–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.A.; Brassel, S.T.; Perumalswami, C.R.; Johnson, T.R.B.; Jagsi, R.; Cortina, L.M.; Settles, I.H. Incidence and Group Comparisons of Harassment Based on Gender, LGBTQ+ Identity, and Race at an Academic Medical Center. J. Women’s Health 2020, 30, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.E.; Montoya, C. Intersectional Mentorship: A Model for Empowerment and Transformation. Political Sci. Politics 2020, 53, 784–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”: Ten Critical Lessons for Black and Other Health Equity Researchers of Color. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Characteristics of Postsecondary Faculty. Condition of Education. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/csc (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Zambrana, R.E.; Ray, R.; Espino, M.M.; Castro, C.; Douthirt Cohen, B.; Eliason, J. “Don’t Leave Us Behind”: The Importance of Mentoring for Underrepresented Minority Faculty. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 52, 40–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; van Diggele, C.; Mellis, C. Mentorship in the health professions: A review. Clin. Teach. 2018, 15, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Louis, G.; Ayappa, I.; Rapoport, D.; Zizi, F.; Airhihenbuwa, C.; Okuyemi, K.; Ogedegbe, G. Mentoring junior URM scientists to engage in sleep health disparities research: Experience of the NYU PRIDE Institute. Sleep Med. 2016, 18, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.; Lee, S.; Bridgman, H.; Thapa, D.K.; Cleary, M.; Kornhaber, R. Benefits, barriers and enablers of mentoring female health academics: An integrative review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H.; Bilge, S. Intersectionality, 2nd ed.; Polity Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg, L. Evolving Intersectionality Within Public Health: From Analysis to Action. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Crenshaw, K.W.; McCall, L. Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis. Signs 2013, 38, 785–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P.; Holden, K.B.; Belton, A. Strategies for Achieving Health Equity: Concern about the Whole Plus Concern about the Hole. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P. Addressing Violence Against Children Through Anti-racism Action. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Parker Dominguez, T. Abandon “Race.” Focus on Racism. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 689462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Else-Quest, N.M.; Hyde, J.S. Intersectionality in Quantitative Psychological Research: II. Methods and Techniques. Psychol. Women Q. 2016, 40, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, L. “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process and practice of reflexivity. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, J.N.; Watkins, C.E. Cultural humility: The cornerstone of positive contact with culturally different individuals and groups? Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 661–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, J.N.; Davis, D.E.; Owen, J.; Worthington, E.L., Jr.; Utsey, S.O. Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E.; Jones, R.; Tipene-Leach, D.; Walker, C.; Loring, B.; Paine, S.J.; Reid, P. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, C.H.; Williams, M.; Kaur, K.; DeBaun, M.R. Academic Medicine’s Journey Toward Racial Equity Must Be Grounded in History: Recommendations for Becoming an Antiracist Academic Medical Center. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 1507–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, U. Why Black Doctors Like Me Are Leaving Academic Medicine. STAT. 2020. Available online: www.statnews.com/2020/01/16/black-doctors-leaving-faculty-positions-academic-medical-centers/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Osseo-Asare, A.; Balasuriya, L.; Huot, S.J.; Keene, D.; Berg, D.; Nunez-Smith, M.; Genao, I.; Latimore, D.; Boatright, D. Minority Resident Physicians’ Views on the Role of Race/Ethnicity in Their Training Experiences in the Workplace. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e182723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzl, J.M.; Roberts, D.E. Structural competency meets structural racism: Race, politics, and the structure of medical knowledge. Virtual Mentor 2014, 16, 674–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, J.E.; Campbell, K.M.; Pololi, L.H. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: What of the minority tax? BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N.; Ravenell, J.; Duncan, A.F.; Butler, M.; Jean-Louis, G.; Kalet, A. Peer Mentor Development Program: Lessons Learned in Mentoring Racial/Ethnic Minority Faculty. Ethn. Dis. 2020, 30, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, J.L. The Role of Sponsorship in Achieving Workforce Diversity in Academic Pediatrics. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20191532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginther, D.K.; Schaffer, W.T.; Schnell, J.; Masimore, B.; Liu, F.; Haak, L.L.; Kington, R. Race, Ethnicity, and NIH Research Awards. Science 2011, 333, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, T.A.; Litovitz, A.; Willis, K.A.; Meseroll, R.A.; Perkins, M.J.; Hutchins, B.I.; Davis, A.F.; Lauer, M.S.; Valantine, H.A.; Anderson, J.M.; et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Ecological Mentoring Levels | Relationship to Intersectional Dynamics of Power in the Mentoring Relationship | Competencies | Praxis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mentor | Understanding | Understanding how one’s intersectional social positions shape their experiences of the institutional environment as well as the mentoring relationship (e.g., experiences of microaggressions, implicit bias) Ability to mentor with cultural humility | Actively reflecting on own lived experience in relation to social power and position Acknowledging one’s own biases and privileges Through self-awareness, actively seek opportunities for continues learning to identify cultural blind spots that might impact the mentoring relationship |

| Mentor–mentee dyad | Understanding, engaging with | Creating space and opportunities for the mentor–mentee relationship to evolve into new ways of relating Actively engaging with and understanding the evolving needs of the mentee throughout mentor/mentee relationship | Inviting open, ongoing dialogue with mentees about their experiences of the mentor/mentee relationship. Solicit feedback from the mentee on ways of improving the mentor/mentee relationship. |

| Academic institution | Engaging with | Ability to structure the mentoring relationship to minimize harmful power dynamics Ability to comfortable explore lived experience of mentees Ability to support mentees in navigating experiences of bias and discrimination | Inviting open, ongoing dialogue with mentees about their experiences of oppression Acknowledge mutual benefits of the mentoring relationship (e.g., mentee has access to mentor’s expertise and networks, mentor benefits from the labor of the trainee, both may learn new skills and content from each other) |

| Academic culture | Transforming | Ability to work collaboratively with mentees toward transforming harmful institutional practices | Advocating on behalf of mentees while centering mentees voices Contributing to decision-making processes, e.g., serving on faculty recruitment committees to ensure consideration of diversity metrics Creating opportunities for mentees and other URM investigators, e.g., helping them to build a network of mentors, providing sponsorship, creating new training programs with the needs of diverse investigators in mind, identifying funding opportunities to support URM investigators (e.g., NIH diversity supplements) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sevelius, J.M.; Harris, O.O.; Bowleg, L. Intersectional Mentorship in Academic Medicine: A Conceptual Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040503

Sevelius JM, Harris OO, Bowleg L. Intersectional Mentorship in Academic Medicine: A Conceptual Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(4):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040503

Chicago/Turabian StyleSevelius, Jae M., Orlando O. Harris, and Lisa Bowleg. 2024. "Intersectional Mentorship in Academic Medicine: A Conceptual Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 4: 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040503

APA StyleSevelius, J. M., Harris, O. O., & Bowleg, L. (2024). Intersectional Mentorship in Academic Medicine: A Conceptual Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(4), 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040503