Effectiveness of Point of Entry Health Screening Measures among Travelers in the Detection and Containment of the International Spread of COVID-19: A Review of the Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

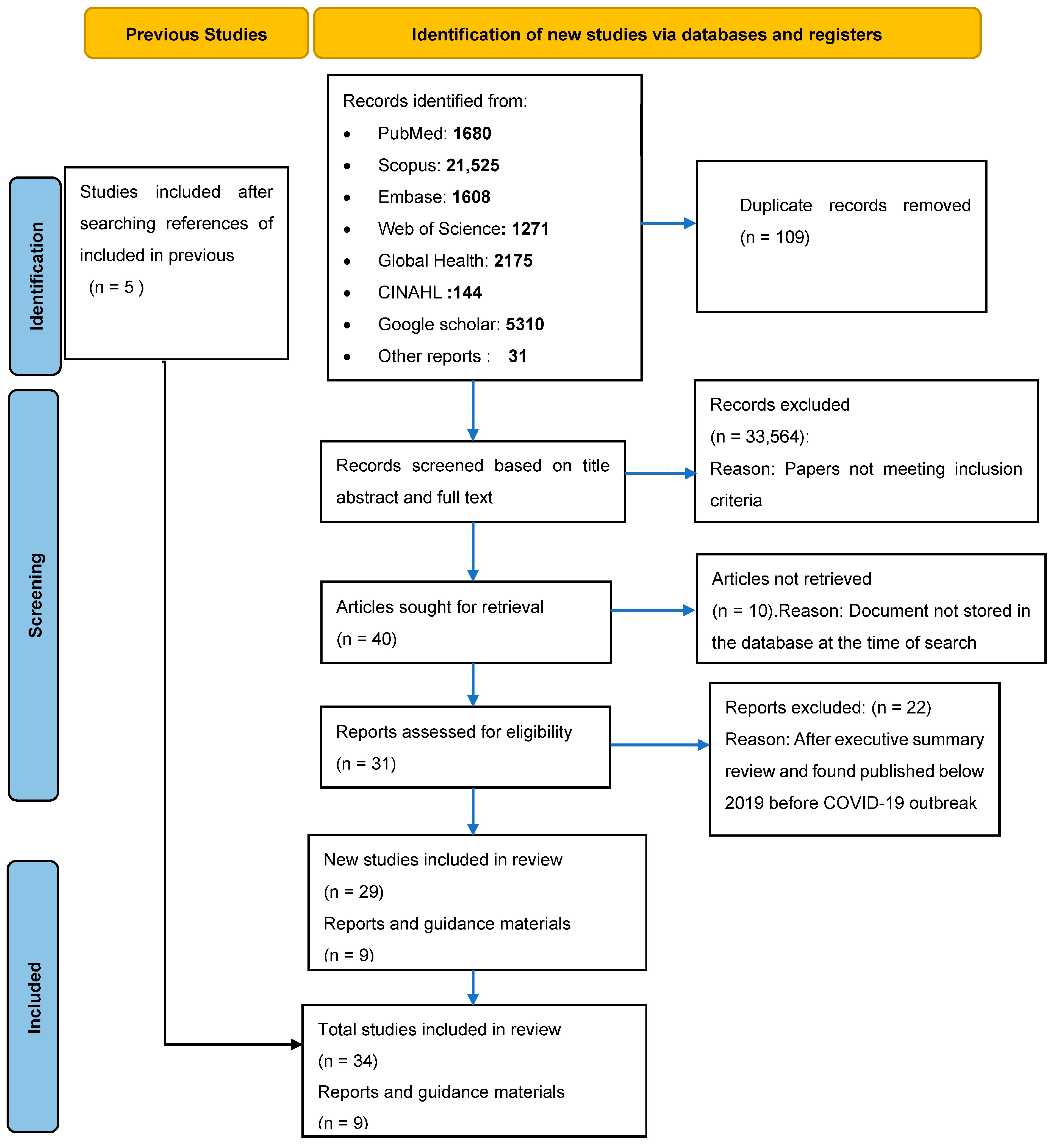

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Sources

2.5. Search Strategy

2.5.1. Search Topics and Definitions

- (a)

- Points of Entry: as defined under the IHR, 2005, as a passage for international entry or exit of travelers, baggage, cargo, containers, conveyances, goods and postal parcels as well as agencies and areas providing services to them on entry or exit;

- (b)

- Entry health screening: public health measures (such as temperature screening, visual inspection for signs of illness, exposure and travel history assessment and testing) implemented at POEs upon arrival with the purpose of identifying travelers infected with or exposed to COVID-19 to mitigate importation of COVID-19;

- (c)

- Exit health screening: public health measures (such as temperature screening, visual inspection for signs of illness, exposure and travel history assessment and testing) implemented at POEs before departure with the purpose of identifying travelers infected or exposed to COVID-19 to prevent exportation of COVID-19 to other countries;

- (d)

- COVID-19 detection: confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 virus through accepted methods;

- (e)

- Travelers: passengers and crew under international voyage.

2.5.2. Search Terms

2.6. Data Extraction (Selection and Coding)

2.7. Quality of Included Articles

2.8. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Screening Strategies Used at Points of Entry

3.2. Effectiveness of POE Screening in the Detection, Delay and Reduction in Transmission of COVID-19

3.2.1. Predictive Models on the Ability of POEs in the Detection, Delay and Reduction in Transmission of COVID-19

3.2.2. Observational Studies on the Ability of POEs to Detect COVID-19 Cases

Confirmed Cases Detected through POE Screening at Points of Entry

Comparison between COVID-19 Cases Detected through POE Screening and Other Public Health Interventions

Detection of COVID-19 Cases through POE Testing Strategy and Genetic Sequencing

Detection of COVID-19 Cases through POE Symptom and Temperature Screening Strategy

3.2.3. Guidelines and Documents Published by the WHO and CDC to Guide Screening for COVID-19 at POE

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, Y.-R.; Cao, Q.-D.; Hong, Z.-S.; Tan, Y.-Y.; Chen, S.-D.; Jin, H.-J.; Tan, K.-S.; Wang, D.-Y.; Yan, Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—An update on the status. Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royce, K. Application of a novel mathematical model to identify intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2. J. Theor. Biol. 2021, 526, 110761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Imtiaz, M.A.; Islam, M.M.; Tanzin, A.Z.; Islam, A.; Hassan, M.M. Major bat-borne zoonotic viral epidemics in Asia and Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 1787–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, H.F.; Mousa, M.; Alefishat, E.; Osman, W.; Spence, I.; Bu, D.; Feng, S.F.; Byrd, J.; Magni, P.A.; Sahibzada, S. Evolution, ecology, and zoonotic transmission of betacoronaviruses: A review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. COVID-19 Epidemiological Update; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- WHO. Statement on the Fourteenth Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2023-statement-on-the-fourteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- WHO. COVID-19 Epidemiological Update—29 September 2023, Edition 159. 2023. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/4864061/covid-19-weekly-epidemiological-update-edition-159-29-september-2023/5701117/ (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Vata, A.; Miftode, L.; Obreja, M.; Miftode, R.; Vata, L.G. Infectious diseases and the air travel—A new pandora’s box? Rom. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 23, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, T.; Daniels, B.B.; Ngandu, N.K.; Goga, A. A rapid review of the effectiveness of screening practices at airports, land borders and ports to reduce the transmission of respiratory infectious diseases such as COVID-19. S. Afr. Med. J. 2020, 110, 1105–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Evidence review—Public health measures in the aviation sector in the context of COVID-19: Quarantine and isolation (21 May 2021)—Examen des données factuelles—Mesures de santé publique dans le secteur du transport aérien dans le contexte de la COVID-19: Quarantaine et isolement (21 mai 2021). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. Relev. Épidémiologique Hebd. 2021, 96, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bitar, D.; Goubar, A.; Desenclos, J.C. International travels and fever screening during epidemics: A literature review on the effectiveness and potential use of non-contact infrared thermometers. Euro Surveill. Bull. Eur. Sur Les Mal. Transm. Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2009, 14, 19115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostic, K.M.; Kucharski, A.J.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O. Effectiveness of traveller screening for emerging pathogens is shaped by epidemiology and natural history of infection. eLife 2015, 4, e05564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiura, H.; Kamiya, K. Fever screening during the influenza (H1N1-2009) pandemic at Narita International Airport, Japan. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, H.; Griffin, S.J.; Kuhn, I.; Usher-Smith, J.A. Software tools to support title and abstract screening for systematic reviews in healthcare: An evaluation. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, S.; Monaco, D.; Turci, C.; Ursino, S.; Matera, C.; Marchini, R.; Di Giovanni, T.; Ciambella, E.; Iannucci, V.; Quintavalle, G. Prevention of the spread of SARS COV-2 by Rapid Antigenic Tests on the passengers entering an Italian seaport. Ann. Ig. Med. Prev. Comunita 2021, 33, 518–520. [Google Scholar]

- Yokota, I.; Shane, P.Y.; Teshima, T. Logistic advantage of two-step screening strategy for SARS-CoV-2 at airport quarantine. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 43, 102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavita, F.; Vairo, F.; Meschi, S.; Valli, M.B.; Lalle, E.; Castilletti, C.; Fusco, D.; Spiga, G.; Bartoletti, P.; Ursino, S.; et al. COVID-19 Rapid antigen test as screening strategy at points of entry: Experience in Lazio region, central Italy, August–October 2020. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipimo, P.J.; Barradas, D.T.; Kayeyi, N.; Zulu, P.M.; Muzala, K.; Mazaba, M.L.; Hamoonga, R.; Musonda, K.; Monze, M.; Kapata, N.; et al. First 100 Persons with COVID-19—Zambia, 18 March–28 April 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1547–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, V.; Bulir, D.; De Prophetis, E.; Jamil, M.; Rosella, L.C.; Mertz, D.; Regehr, C.; Smieja, M. COVID-19 international border surveillance at Toronto’s Pearson Airport: A cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertollini, R.; Chemaitelly, H.; Yassine, H.M.; Al-Thani, M.H.; Al-Khal, A.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. Associations of vaccination and of prior infection with positive PCR test results for SARS-CoV-2 in airline passengers arriving in Qatar. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2021, 326, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspe, R.C.; Sulbaran, Y.; Loureiro, C.L.; Moros, Z.C.; Marulanda, E.; Bracho, F.; Ramírez, N.A.; Canonico, Y.; D’Angelo, P.; Rodríguez, L.; et al. Detection of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 in international travelers returning to Venezuela. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 48, 102326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nsawotebba, A.; Ibanda, I.; Ssewanyana, I.; Ogwok, P.; Ocen, F.; Okiira, C.; Kagirita, A.; Mujuni, D.; Tugumisirize, D.; Kabugo, J.; et al. Effectiveness of thermal screening in detection of COVID-19 among truck drivers at Mutukula Land Point of Entry, Uganda. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, D.A.; Ahmed, J.Q.; Qader, M.K.; Shukur, M.S.; Zeebaree, B.K.A.; Sadeq, M.B.; Mohammed, S.N.; Masiha, H.N.; Abdullah, I.M.; Mohammed, O.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 and RT-PCR testing in travelers: Results of a cross-sectional study of travelers at Iraq’s international borders. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 2422–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekizuka, T.; Itokawa, K.; Yatsu, K.; Tanaka, R.; Hashino, M.; Kawano-Sugaya, T.; Ohnishi, M.; Wakita, T.; Kuroda, M. COVID-19 genome surveillance at international airport quarantine stations in Japan. J. Travel Med. 2020, 28, taaa217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subedee, K.C.; Poudel, K.P.; Khogali, M.; Pokhrel, A.; Chinnakali, P.; Thakur, N.; Timsina, D.; Gautam, R.; Rahman, A.; Mandal, S.K.; et al. COVID-19 Amongst Travelers at Points of Entry in Nepal: Screening, Testing, Diagnosis and Isolation Practices. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, M.; Hachiya, M.; Ohtsu, H.; Akashi, H.; Miyoshi, C.; Umeda, T. Epidemiology and Risk of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Among Travelers at Airport and Port Quarantine Stations Across Japan: A Nationwide Descriptive Analysis and an Individually Matched Case-Control Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsen, E.C.; Porter, K.A.; Mooring, E.; Cutchins, C.; Zink, A.; McLaughlin, J. Airport Traveler Testing Program for SARS-CoV-2—Alaska, June–November 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, P.; Griffin, I.; Berro, A.; Cohen, N.J.; Singler, K.; Haber, Y.; de la Motte Hurst, C.; Stolp, A.; Atti, S.; Hausman, L.; et al. Risk Assessment and Management of COVID-19 Among Travelers Arriving at Designated U.S. Airports, 17 January–13 September 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, C.; Krishnankutty, S.L.; Khader, K.; Kanmani, A.K.; Rahul, A.; Suresh, M.M.; Sudha, R.R.; Indu, P.S. Entry screening at airport as a COVID-19 surveillance tool: Evaluation of Thiruvananthapuram International Airport in Kerala, India. Int. J. Travel Med. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.W.; Kim, D.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, S. Symptoms and Characteristics Which Require Attention During COVID-19 Screening at a Port of Entry. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasi, A.R.; Gaikwad, P.B.; Aroskar, K.; Kumar, T.; Teddy, R.; Kundu, M.; Naag, R.; Khasnobis, P.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Sen, P.K. Early detection of suspected cases of COVID-19: Role of thermal screening at international airports in India. Int. J. Commun. Med. Public Health 2020, 7, 4817–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-Y.; Chen, T.-J.; Hwang, S.-J. Analysis of imported cases of COVID-19 in Taiwan: A nationwide study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamaila, U.; Afreen, S.; Khurram, S.; Baig, Z.I.; Khan, M.A.; Malik, M.W.; Jamil, A.; Nausheen, A. Descriptive analysis of health screening for COVID-19 at points of entry in Pakistan according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. Int. J. Travel Med. Glob. Health 2022, 10, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Aroskar, K.; Sahu, R.; Choudhary, S.; Pasi, A.R.; Gaikwad, P.; Dikid, T. Evaluation of point of entry surveillance for COVID-19 at Mumbai international airport, India, July 2020. Indian J. Public Health 2022, 66, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quilty, B.J.; Clifford, S.; Flasche, S.; Eggo, R.M. Effectiveness of airport screening at detecting travellers infected with novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Euro Surveill. Bull. Eur. Sur Les Mal. Transm. Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2020, 25, 2000080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, D.; Bennett, E.; Finnie, T. What effect might border screening have on preventing the importation of COVID-19 compared with other infections? A modelling study. Epidemiol. Infect. 2021, 149, e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, B.L.; Koo, J.R.; Lim, J.T.; Park, M.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Quaye, S.E.D.; Clapham, H.E.; Wee, H.L.; et al. Determining quarantine length and testing frequency for international border opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28, taab088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gostic, K.M.; Gomez, A.C.R.; Mummah, R.O.; Kucharski, A.J.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O. Estimated effectiveness of symptom and risk screening to prevent the spread of COVID-19. eLife 2020, 9, e55570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, D.; Bennett, E.; Finnie, T. What effect might border screening have on preventing importation of COVID-19 compared with other infections?: Considering the additional effect of post-arrival isolation. Epidemiol. Infect. 2022, 150, e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, S.; Pearson, C.A.; Klepac, P.; Van Zandvoort, K.; Quilty, B.J.; CMMID COVID-19 Working Group; Eggo, R.M.; Flasche, S. Effectiveness of interventions targeting air travellers for delaying local outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuckchady, D. Impact of public health interventions on the COVID-19 epidemic: A stochastic model based on data from an African island. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Bhatnagar, T.; Arinaminpathy, N.; Agarwal, A.; Chowdhury, A.; Murhekar, M.; Gangakhedkar, R.R.; Sarkar, S. Prudent public health intervention strategies to control the coronavirus disease 2019 transmission in India: A mathematical model-based approach. Indian J. Med. Res. 2020, 151, 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M.A.; Wolford, H.; Paul, P.; Diaz, P.S.; Chen, T.-H.; Brown, C.M.; Cetron, M.S.; Alvarado-Ramy, F. Reducing travel-related SARS-CoV-2 transmission with layered mitigation measures: Symptom monitoring, quarantine, and testing. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, B.L.; Koo, J.R.; Lim, J.T.; Sun, H.; Clapham, H.E.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Cook, A.R. Strategies at points of entry to reduce importation risk of COVID-19 cases and reopen travel. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.P.; Junus, A.; Zhu, X.; Jia, P.; Wen, T.; Pfeiffer, D.; Yuan, H. The effects of border control and quarantine measures on the spread of COVID-19. Epidemics 2020, 32, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, N.; Lustig, A.; Hendy, S.C.; Binny, R.N.; Plank, M.J. Effect of vaccination, border testing, and quarantine requirements on the risk of COVID-19 in New Zealand: A modelling study. Infect. Dis. Model. 2022, 7, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Tsang, T.K.; Wong, J.Y.; He, Y.; Gao, H.; Ho, F.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wu, P.; Sullivan, S.G.; Cowling, B.J. The differential importation risks of COVID-19 from inbound travellers and the feasibility of targeted travel controls: A case study in Hong Kong. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 13, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiang, M.V.; Chin, E.T.; Huynh, B.Q.; Chapman, L.A.C.; Rodríguez-Barraquer, I.; Greenhouse, B.; Rutherford, G.W.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Havlir, D.; Basu, S.; et al. Routine asymptomatic testing strategies for airline travel during the COVID-19 pandemic: A simulation study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, S.W.; Han, N.; Liu, Z.M.; Xiao, W.W.; Jiang, B.Q.; Han, M.X. The analysis of the characteristics of imported COVID-19 cases from January to April in 2020: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Technical Considerations for Implementing a Risk-Based Approach to International Travel in the Context of COVID-19: Interim Guidance: Annex to: Policy Considerations for Implementing a Risk-Based Approach to International Travel in the Context of COVID-19, 2 July 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Operational Framework for International Travel-Related Public Health Measures in the Context of COVID-19; World Health Organization; Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Policy Considerations for Implementing a Risk-Based Approach to International Travel in the Context of COVID-19, 2 July 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Considerations for Sharing Information for International Contact Tracing in the Context of COVID-19; World Health Organization; Regional Office for South-East Asia: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Management of Ill Travellers at Points of Entry (International Airports, Seaports, and Ground Crossings) in the Context of COVID-19, Interim Guidance, 19 March 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 Infection at Air, Land, and Sea Points of Entry and Complementary Measures to Limit International Spread of COVID-19: Strategies for Port Health Leaders Outside the United States. 2022. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/132848 (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- CDC. Tool to Prioritize Points of Entry and Points of Control (TOP POE/C) Considerations for Prioritizing Points of Entry and Control for Public Health Capacity Building. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/prioritize-poe-tool.html (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Cheng, H.Y.; Chueh, Y.N.; Chen, C.M.; Jian, S.W.; Lai, S.K.; Liu, D.P. Taiwan’s COVID-19 response: Timely case detection and quarantine, January to June 2020. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. Taiwan Yi Zhi 2021, 120, 1400–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, J.; Movsisyan, A.; Stratil, J.M.; Coenen, M.; Emmert-Fees, K.M.; Geffert, K.; Hoffmann, S.; Horstick, O.; Laxy, M.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; et al. Travel-related control measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 10, CD013717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cardwell, K.; Jordan, K.; Byrne, P.; Smith, S.M.; Harrington, P.; Ryan, M.; O’Neill, M. The effectiveness of non-contact thermal screening as a means of identifying cases of Covid-19: A rapid review of the evidence. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunaratnam, P.J.; Tobin, S.; Seale, H.; Marich, A.; McAnulty, J. Airport arrivals screening during pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza in New South Wales, Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 200, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, P.; Liyanage, S.; Seale, H.; Deng, Y.; Pang, X.; Tian, L.; Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q. The characteristics of imported cases and the effectiveness of outbreak control strategies of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in China. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2012, 24, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neha, M.; Joshi, N.K.; Pankaj, B.; Goel, A.D.; Gupta, M.K.; Kuldeep, S.; Sanjeev, M. Barriers and facilitators to COVID-19 screening at Jaipur International Airport, India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 5969–5982. [Google Scholar]

- Ndoungué, V.F.; Ngapagna, A.N.; Kouadio, S.A.; Djinguebey, R.; Gnigninanjouena, O.; Eyangoh, S.; Nguefack-Tsague, G.; Djeunga, H.C.N.; Njajou, O. Assessing core capacities for addressing public health emergencies of international concern at designated points of entry in Cameroon during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awoonor-Williams, J.K.; Moyer, C.A.; Adokiya, M.N. Self-reported challenges to border screening of travelers for Ebola by district health workers in northern Ghana: An observational study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastiti, R.D.; Artanti, K.D.; Faqih, A.F. Analysis of epidemiological surveillance activity of the COVID-19 at Surabaya Airport Indonesia on January 2020. Kesmas Natl. Public Health J. 2020, 1, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lokossou, V.K.; Usman, A.B.; Sombie, I.; Paraiso, M.N.; Balogun, M.S.; Umeokonkwo, C.D.; Gatua, J.; Wagai, J.; Ouendo, E.M.; Nguku, P. COVID-19 pandemic in Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) region: Implication for capacity strengthening at Point of Entry. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Intervention | Setting | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | |||

| Coronavirus | |||

| travel* | S-COVID-19 | ||

| passenger | point of entry | Coronavirus disease 2019 | |

| crew* | screen* | port of entry | SARS-CoV-2 |

| driver* | measure* | depart* | Covid infection |

| conductor* | IR system* | arriv* | 2019 Novel Coronavirus |

| truck driver* | thermal scan* | airport* | Covid disease |

| tourist* | non-contact thermometer* | point of departure | 2019-nCoV |

| non-contact infrared thermometer* | seaport* | Coronavirus Disease 2019 | |

| questionnaire* | port* | COVID-19 Virus | |

| visual observation | entry point* | Virus Infection | |

| non-contact infrared camera* | quarantine station* | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona virus2 | |

| infrared thermo* | railway station* | SARS Coronavirus2 | |

| surveillance form* | border* | Virus Disease | |

| surveillance | ground crossing* | Pandemic | |

| sign* | exit point | Epidemic | |

| symptom* | Wuhan* |

| Country/POE | Exposure Assessment | Sign and Symptom Assessment/Self-Declaration | Temperature Measurement | Testing | Other | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India: Thiruvananthapuram International Airport | NR | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | [31] |

| Republic of Korea: Incheon International Airport | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | NR | [32] |

| Italy: Sea port | NR | NR | NR | Yes | NR | [17] |

| India: Cochin, Delhi Kolkata and Mumbai airports | NR | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | [33] |

| India: Mumbai International Airport | NR | NR | Yes | NR | NR | [36] |

| Japan: Three international airports | NR | NR | NR | Yes | NR | [18] |

| Italy: international airports in Rome and port of Civitavecchia | NR | NR | NR | Yes | NR | [19] |

| Zambia: Points of entry surveillance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes for symptomatic | Daily telephone call for 14 days | [20] |

| Canada: Toronto’s Pearson International Airport | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | NR | [21] |

| Taiwan | NR | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | [34] |

| Quatar: Hamand International Airport | NR | NR | NR | Yes | Vaccination status of travelers | [22] |

| Venezuela: Maiquetia airport | NR | NR | NR | Testing and sequencing | NR | [23] |

| Uganda: Mutukula border | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | NR | [24] |

| Iraq: Ibrahim Al-Khalil border | NR | NR | NR | Yes | NR | [25] |

| Japan: Narita, Hanada, Nagoya and Kansai airports | NR | NR | NR | Testing and sequencing | NR | [26] |

| Pakistan: Seven airports | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | [35] |

| Nepal: 13 designated borders | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes for suspect travelers or without negative RT-PCR | RT-PCR test certificates | [27] |

| Japan: Five major airports | NR | Yes | NR | Yes | NR | [28] |

| Alaska: 10 airports | NR | NR | NR | Yes | NR | [29] |

| USA: 15 designated airports | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes for suspects | NR | [30] |

| (a) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title of Study | Model Type | Detection of Positive COVID-19 Cases | Ref. | |

| Exit Health Screening | Entry Health Screening | |||

| 1. Effectiveness of airport screening at detecting travelers infected with novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) | Simulation | 44% | 9% | [37] |

| 2. What effect might border screening have on preventing the importation of COVID-19 compared with other infections? A modeling study | Mathematical Modeling | NR | 8.8% | [38] |

| 3. What effect might border screening have on preventing importation of COVID-19 compared with other infections? Considering the additional effect of post-arrival isolation | Simulation | Single arrival test could detect 9% and combined with 8 days, isolation detection could reach 94% | [41] | |

| 4. Determining quarantine length and testing frequency for international border opening during the COVID-19 pandemic | Simulation | At a prevalence of 0.1% to 2% per million travelers, exit and entry testing by PCR combined with quarantine at 7, 14 and 21 days reduced missed cases at rates of 4.9%, 1.5% and 0.4%, respectively, and using rapid antigen testing, the reduction was at 3.6%, 2.8% and 0.7%, respectively. | [39] | |

| 5. Estimated effectiveness of symptom and risk screening to prevent the spread of COVID-19 | Mathematical modeling | In the growing epidemic, under the assumption that 5% were subclinical, departure and arrival screenings detected 0.3% of infected travelers. While in the stable epidemic, with 25% being subclinical, arrival screenings alone detected one third (17–53%), and departure and arrival detected half (23–63%) | [40] | |

| (b) | ||||

| Title of Study | Model Type | Delay of COVID-19 Outbreaks and Reduction in Transmission Risk of Positive Cases | Ref. | |

| 1. Effectiveness of interventions targeting air travelers for delaying local outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 | Stochastic model | POE entry and exit screenings, combined with traveler sensitization, delayed an outbreak by 8 days (50% interval: 3–14 days) | [42] | |

| 2. Impact of public health interventions on the COVID-19 epidemic: A stochastic model based on data from an African island | Stochastic model | A POE screening at 64% or 100% sensitivity delayed the onset of the COVID-19 epidemic for 10 to 20 days, respectively | [43] | |

| 3. Prudent public health intervention strategies to control the coronavirus disease 2019 transmission in India: A mathematical model-based approach | Mathematical model | If all symptomatic travelers were identified and 90% were asymptomatic, diagnosed POE screening could delay the epidemic by up to 20 days | [44] | |

| 4. Reducing travel-related SARS-CoV-2 transmission with layered mitigation measures: Symptom monitoring, quarantine and testing | Mathematical model | Symptom check at departure reduced risk of transmission for 30–35%, exit screening (testing) reduced the transmission risk by 44–72% and symptom evaluation reduced the risk of importation by 42–56% | [45] | |

| 5. Strategies at points of entry to reduce importation risk of COVID-19 cases and reopen travel | Simulation | Testing all travelers, isolating the positive and permitting entry after a negative test result at day 14 reduced importation risk by 91.7% | [46] | |

| 6. The effects of border control and quarantine measures on the spread of COVID-19 | Mathematical model | At reproductive numbers (Ros) of 1.4, 1.68 and 2.92, border control could delay (above threshold of 8 cases in the community) the onset of outbreak for 32.5, 20 and 10 days, respectively | [47] | |

| 7. Effect of vaccination, border testing and quarantine requirements on the risk of COVID-19 in New Zealand: A modeling study | Mathematical model | Three-day pre-departure PCR test, followed by two PCR tests post-arrival (at 0 and 4 days) and managed isolation quarantine (MIQ) for seven days reduced COVID-19 transmission risk to 0.35 and 0.18 among non-vaccinated and vaccinated travelers, respectively, and a fourteen-day stay in MIQ with two PCR tests reduced the transmission potential to a negligible level | [48] | |

| 8. The differential importation risks of COVID-19 from inbound travelers and the feasibility of targeted travel controls: A case study in Hong Kong | Modeling study | On arrival, testing prevented an average of 40–42% of infectious travelers at the airport from mixing with the community | [49] | |

| 9. Routine asymptomatic testing strategies for airline travel during the COVID-19 pandemic: A simulation study | Simulation | Rapid antigen testing performed on day of departure was associated with reduction in infectious days by 32% and active infections of SARS-CoV-2 by 86%; when combined with a day 5 PCR test and 5 days of quarantine, infectious days were reduced by 70% and active infections, by 86% | [50] | |

| (a) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Title of Study | International Airport | Travelers Screened | Duration | Suspects Detected at Airport | Confirmed | Ref. |

| Kerala, India | Entry screening at airport as a COVID-19 surveillance tool (pre-lockdown) | Thiruvananthapuram | 46,139 | 29 January to 24 March 2020 | 320 | 6 (1.9%) | [31] |

| Kerala, India | Entry screening at airport as a COVID-19 surveillance tool (post-lockdown) | Thiruvananthapuram | 44,263 | 13 May to 31 July 2020 | 684 | 12 (1.8%) | [31] |

| India | Early detection of suspected cases of COVID-19: Role of thermal screening at international airports in India | Cochin, Delhi, Kolkata and Mumbai | 1,587,034 | 17 January to 30 September 2020 | 151 | 0 (0%) | [33] |

| India | Evaluation of point of entry surveillance for COVID-19 at Mumbai International Airport | Mumbai | 165,882 | 1 to 22 March 2020 | 3 | 0 (0%) | [36] |

| Canada | COVID-19 international border surveillance at Toronto’s Pearson Airport: A cohort study | Pearson | 16,361 | September to October 2020 | NR | 167 | [21] |

| Quatar | Associations of vaccination and of prior infection with positive PCR test results for SARS-CoV-2 in airline passengers arriving in Qatar | Hamad | 247,091 | 18–26 February April 2021 | NR | 8319 | [22] |

| Japan | COVID-19 genome surveillance at international airport quarantine stations in Japan | Narita, Hanada, Nagoya and Kansai | 168,061 | March to 1 September 2020 | NR | 782 | [26] |

| Pakistan | Descriptive analysis of health screening for COVID-19 at points of entry in Pakistan according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines | Seven international airports | 361,737 | February 2020 to March 2021 | 375 | NR | [35] |

| Pakistan | Descriptive analysis of health screening for COVID-19 at points of entry in Pakistan according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines | Seven international airports | 74,833 | February 2020 to March 2021 | NR | 243 | [35] |

| Japan | Epidemiology and risk of coronavirus disease 2019 among travelers at airport and port quarantine stations across Japan: A nationwide descriptive analysis and an individually matched case–control study | Five major international airports | 155,087 | August to October 2020 | 558 | 0.35% | [28] |

| Alaska | Airport traveler testing program for SARS-CoV-2—Alaska, June–November 2020 | 10 participating airports | 111,370 | 6 June to 14 November 2020 | 951 | 0.8% | [29] |

| USA | risk assessment and management of COVID-19 Among travelers arriving at designated U.S. airports, 17 January–13 September 2020 | 15 designated international airports | 766,044 | 17 January to 13 September 2020 | 298 | 9 (0.001%) | [30] |

| (b) | |||||||

| Country | Title of Study | International Border/Sea Port | Travelers Screened | Duration | Suspects Detected at POE | Confirmed | Ref. |

| Italia | Prevention of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 by rapid antigenic tests on the passengers entering an Italian seaport | Sea port | 38,282 | 21 August to 27 September 2020 | 272 | 212 (77.9%) | [17] |

| Nepal | COVID-19 amongst travelers at points of entry in Nepal: Screening, testing, diagnosis and isolation practices | 13 designated borders | 337,338 | March to July 2021 | 69,886 | 3907 (6%) | [27] |

| Iraq | SARS-CoV-2 and RT-PCR testing in travelers: Results of a cross-sectional study of travelers at Iraq’s international borders | Ibrahim Al-Khalil border | 1,082,074 | 21 August 2020 to 21 August 2021 | 9873 | 0.9% | [25] |

| Uganda | Effectiveness of thermal screening in detection of COVID-19 among truck drivers at Mutukula land point of entry, Uganda | Mutukula border | 7181 | 15 May to 30 July 2020 | 83 suspected by thermal scanner | 48 (57.8%), actual confirmed cases by Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 assay, 483; thus, detection rate of 10% | [24] |

| Country, POE | Detection Strategy | Travelers Screened | Suspected/Total Imported Cases | Confirmed at POE | Proportional COVID-19 Detected at POE | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Rapid test | 38,282 | 272 | 212 | 77.9% | [18] |

| Italy | Rapid test | 73,643 | 1173 | 476 | 40.5 | [19] |

| Toronto, Canada | Rapid test | 16,361 | 248 imported | 167 | 67.30% | [21] |

| Japan | Rapid test | 88,924 | 513 | 34 | 6.60% | [18] |

| Venezuela, Maiquetia airport | Molecular test with sequencing | 256 samples of travelers | NA | Omicron B.1.1 (VOC) | NA | [23] |

| Iraq, Ibrahim Al-Khalil border | RT-PCR | 1,082,074 | NR | 9873 | 0.9% of those screened | [25] |

| Japan | Molecular test with sequencing | 168,061 | NR | 782 | 129 samples sequenced identified lineages from three foreign countries | [26] |

| Pakistan | RT-PCR and rapid antigen test | 74,833 | 243 | [35] | ||

| Japan | Antigen test | 155,087 | 558 | [28] | ||

| Nepal | Lateral flow antigen test | 69,886 | 3907 | 6% positivity | [27] |

| Country | Screening Strategy | Number Screened | Suspected | Confirmed | Proportion Confirmed among Suspects | Proportion Detected at POE among Imported | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Signs and symptoms | 5,291,039 | NR | 1610 | NA | 315 (19.6%) | [51] |

| Taiwan | Signs, symptoms and temperature checks | NR | NR | 320 | NA | 105 (32.7%) | [34] |

| Republic of Korea | Signs, symptoms and temperature checks | 348,753 | 11,074 | 388 | 3.5% | No data on total imported cases | [32] |

| India—Thiruvananthapuram airport | Signs, symptoms and temperature checks | 46,139 | 320 | 6 | 2% | No data on total imported cases | [31] |

| India—Thiruvananthapuram airport | Signs, symptoms and temperature checks | 44,263 | 683 | 45 | 6% | No data on total imported cases | [31] |

| Uganda, Mutukula border | Temperature checks | 7181 | 83 | 48 | 57.8% | 488 (10%) | [24] |

| USA airports | Exposure and symptom screening | 766,044 | 298 | 9 | 3% | No data on total imported cases | [30] |

| India airports | Temperature checks | 1,593,861 | 151 | NR | NR | NR | [33] |

| India, Mumbai International Airport | Temperature checks | 165,882 | 3 | 0 | 0 | NR | [36] |

| Publication | Title | Key Recommendations/Findings |

|---|---|---|

| WHO [52] | Technical considerations for implementing a risk-based approach to international travel in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance: Policy considerations for implementing a risk-based approach to international travel in the context of COVID-19, 2 July 2021 |

|

| WHO [11] | Evidence reviews—Public health measures in the aviation sector in the context of COVID-19: Quarantine and isolation | Through a systematic review, the WHO concluded that the evidence on usefulness of quarantine to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is of low to very low certainty at best and based on a limited number of modeling studies and a few observational series conducted up to 13 November 2020. Therefore, the implementation of international travel and health guidelines and isolation of symptomatic and/or SARS-CoV-2 test-positive travelers were endorsed as a response strategy to the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| WHO [53] | Operational framework for international travel-related public health measures in the context of COVID-19 | The following considerations should be taken onboard when deciding to implement international related public health measures:

|

| WHO [54] | Policy considerations for implementing a risk-based approach to international travel in the context of COVID-19 | Based on evolving evidence and the changing epidemiology of COVID-19, the WHO policy recommends the following for international travel-related public health measures:

|

| WHO [55] | Considerations for sharing information for international contact tracing in the context of COVID-19 | IHR’s national focal point should be used for sharing contact information internationally:

|

| WHO [56] | Management of ill travelers at points of entry (international airports, seaports and ground crossings) in the context of COVID-19 | The interim guidance provides for procedures for the detection and management of ill travelers suspected to have COVID-19 at POEs and on conveyances of all types specifically:

|

| CDC [57] | Testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection at air, land and sea points of entry and complementary measures to limit international spread of COVID-19: Strategies for port health leaders outside the United States | Designing a testing strategy at POEs should consider the following:

|

| CDC [58] | Tool to prioritize point of entry and point of control (POE/C) considerations for prioritizing points of entry and control for public health capacity building | Enhancing capacity building in the prevention of the transmission of communicable diseases through POEs (international) or points of control (domestic) can be prioritized based on the following criteria:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kakulu, R.K.; Kimaro, E.G.; Mpolya, E.A. Effectiveness of Point of Entry Health Screening Measures among Travelers in the Detection and Containment of the International Spread of COVID-19: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040410

Kakulu RK, Kimaro EG, Mpolya EA. Effectiveness of Point of Entry Health Screening Measures among Travelers in the Detection and Containment of the International Spread of COVID-19: A Review of the Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(4):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040410

Chicago/Turabian StyleKakulu, Remidius Kamuhabwa, Esther Gwae Kimaro, and Emmanuel Abraham Mpolya. 2024. "Effectiveness of Point of Entry Health Screening Measures among Travelers in the Detection and Containment of the International Spread of COVID-19: A Review of the Evidence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 4: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040410

APA StyleKakulu, R. K., Kimaro, E. G., & Mpolya, E. A. (2024). Effectiveness of Point of Entry Health Screening Measures among Travelers in the Detection and Containment of the International Spread of COVID-19: A Review of the Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(4), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040410