Sexual Minorities and Loneliness: Exploring Sexuality through Social Media and Gender–Sexuality Alliance (GSA) Supports

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Developing One’s Sexual Orientation Identity

1.2. Social Isolation of LGBTQ+ Youth and Mental Health

1.3. Social Supports for Identity Development of Young Sexual Minority Youth

1.3.1. Online Peer Support via Social Media

1.3.2. Gender–Sexuality Alliances

1.4. LGBTQ+ Youth and Online Community Engagement

1.5. Online Community and Civic Engagement

1.6. Current Study

1.7. Research Questions

- Are LGBTQ+ youth significantly lonelier?

- 2.

- In what ways are less lonely LGBTQ+ youth significantly different from more lonely LGBTQ+ counterparts, such as (a) exploring sexual orientation (e.g., the strength of identifying with sexual orientation, what sources of social support and education do they receive about their sexual orientation) and (b) online community support (e.g., social media platforms used, social media help-seeking preferences, giving and receiving online social support, and online civic engagement)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sexual Orientation

2.2.2. Loneliness

2.2.3. Strength of Sexual Identity

2.2.4. Sources of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Education

2.2.5. Social Media Help-Seeking Preferences

2.2.6. Positive Social Media Engagement

2.2.7. Giving and Receiving Emotional Support on Social Media

2.2.8. Gender

2.3. Sample Description

2.4. Analysis Plan

Covariates

3. Results

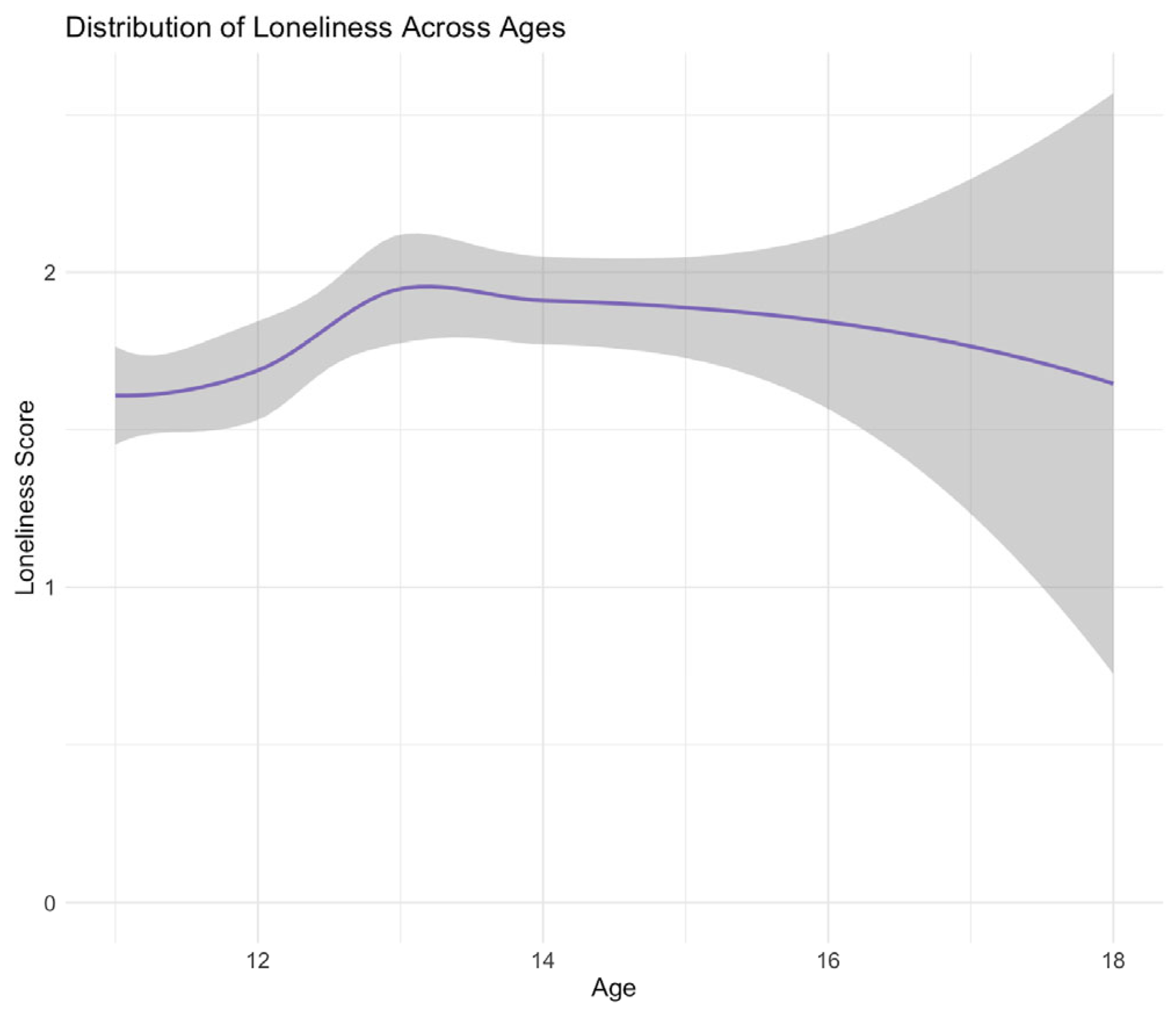

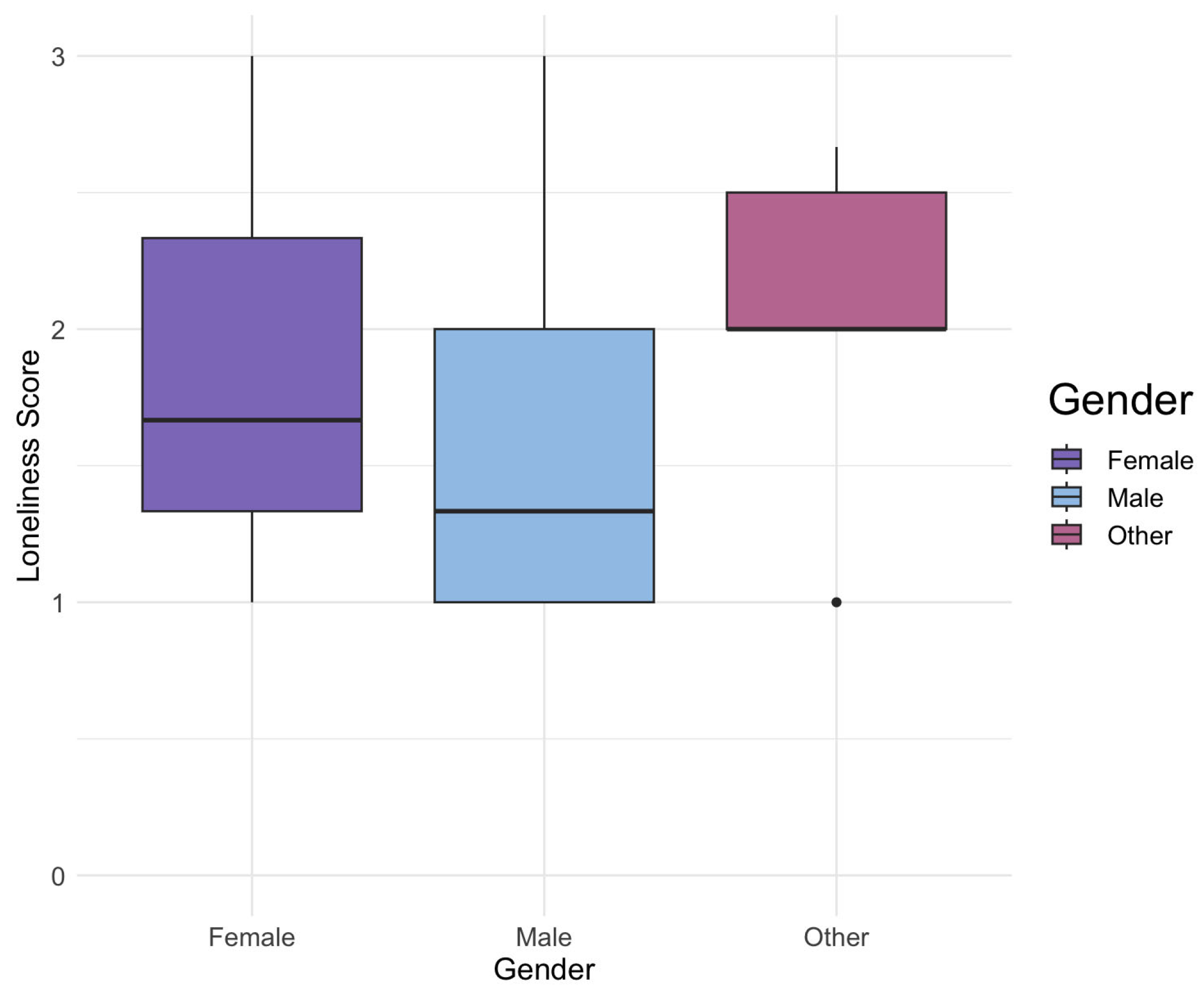

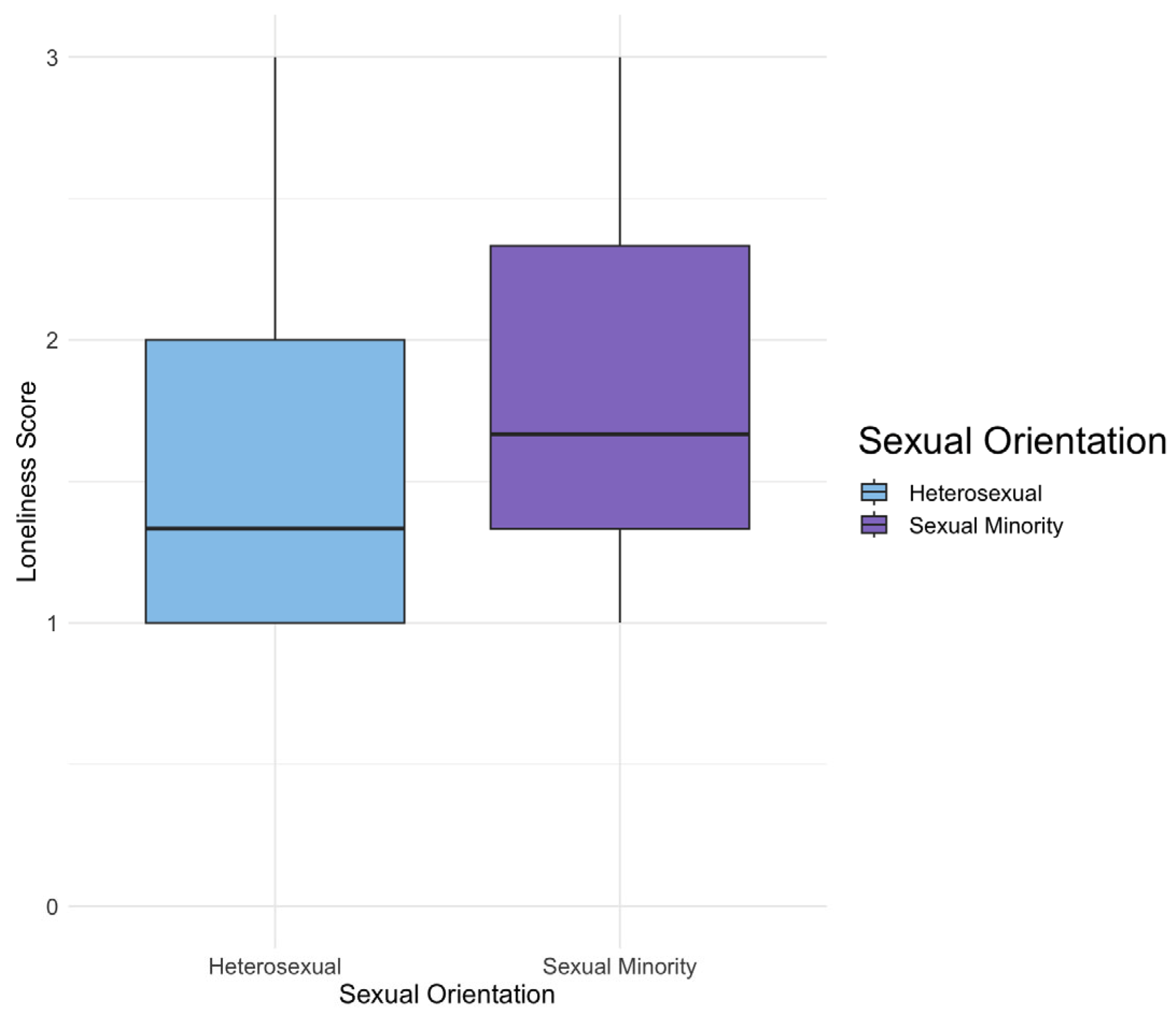

3.1. Are LGBTQ+ Youth More Lonely?

3.2. Sexual Orientation Exploration and Education

3.3. Support and Engagement within Online Communities

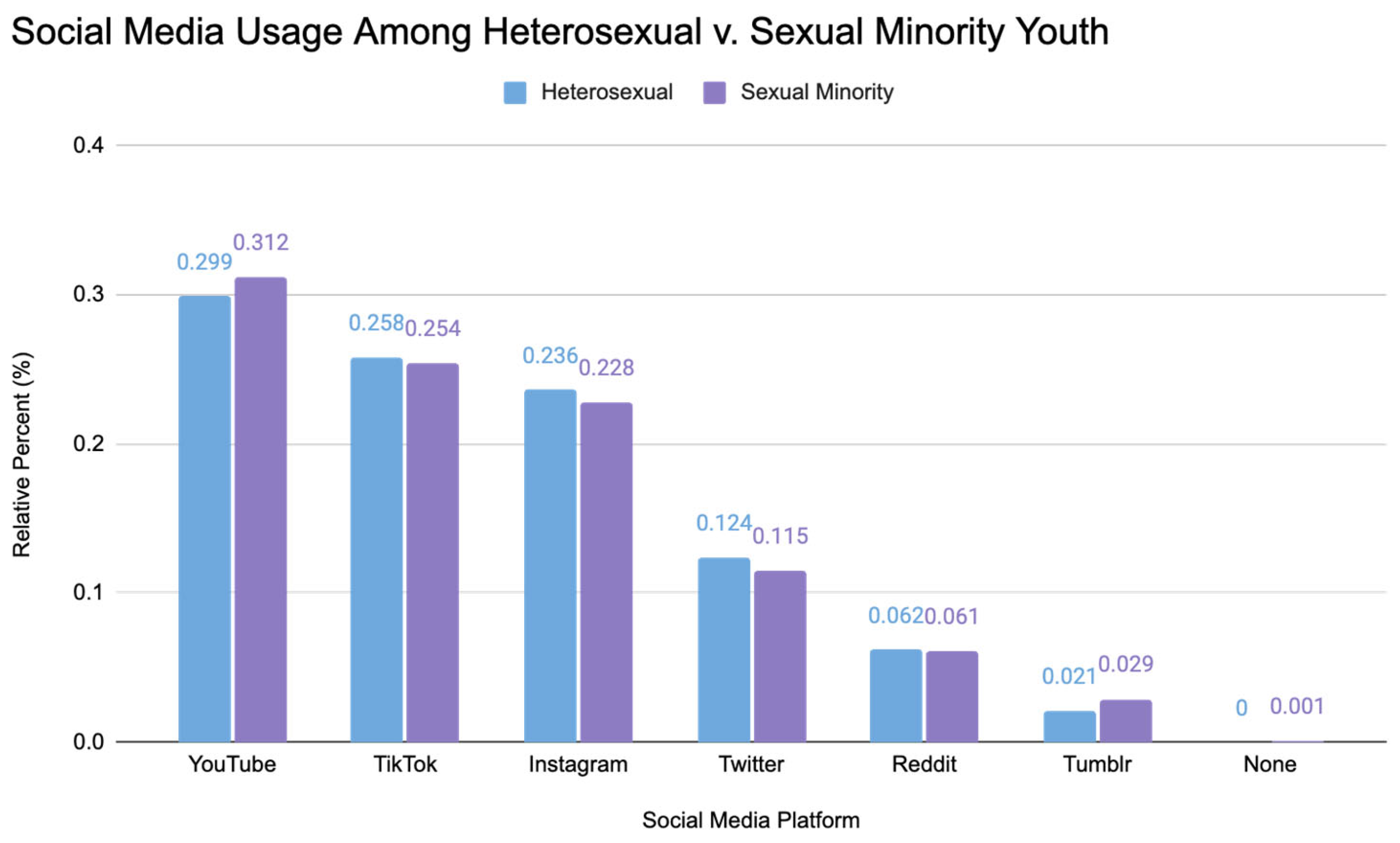

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murthy, V. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The, U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. Office of the Surgeon General. 2023. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Herrmann, W.J.; Oeser, P.; Buspavanich, P.; Lech, S.; Berger, M.; Gellert, P. Loneliness and depressive symptoms differ by sexual orientation and gender identity during physical distancing measures in response to COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2023, 15, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, G.; Loret de Mola, E.; Gavulic, K.A.; McKay, T.; Purcell, C. Mental Health Needs Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaraman, L.; Hernandez, J.M.; Hodes, R. Marginalized and understudied populations using digital media. In Handbook of Adolescent Digital Media Use and Mental Health; Nesi, J., Telzer, E.H., Prinstein, M.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeus, W.; Iedema, J.; Helsen, M.; Vollebergh, W. Patterns of Adolescent Identity Development: Review of Literature and Longitudinal Analysis. Dev. Rev. 1999, 19, 419–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenaway, K.H.; Haslam, S.A.; Cruwys, T.; Branscombe, N.R.; Ysseldyk, R.; Heldreth, C. From “we” to “me”: Group identification enhances perceived personal control with consequences for health and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D.T.; Kwang, T. When the Relationship Becomes Her: Revisiting Women’s Body Concerns from a Relationship Contingency Perspective. Psychol. Women Q. 2007, 31, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Hogg, M.A.; Oakes, P.J.; Reicher, S.D.; Wetherell, M.S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987; Volume 10, p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Trevor Project. Age of Sexual Orientation Outness and Suicide Risk. 2022. Available online: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/age-of-sexual-orientation-outness-and-suicide-risk-oct-2022/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Dubé, E.M.; Savin-Williams, R.C. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual-minority male youths. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaraman, L.; Grossman, J.M.; Richer, A.M. Same-Sex Attraction Disclosure and Sexual Communication Topics within Families. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2021, 17, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, V.P.; Anderson, C.J. Developmental changes in sexual prejudice from early to late adolescence: The effects of gender, race, and ideology on different patterns of change. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’augelli, A.R. Mental Health Problems among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths Ages 14 to 21. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 7, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, R.L.; Kenny, M.C. Cyberbullying and LGBTQ Youth: A Systematic Literature Review and Recommendations for Prevention and Intervention. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2017, 11, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valido, A.; Rivas-Koehl, M.; Rivas-Koehl, D.; Espelage, D.L.; Lawrence, T.I.; Robinson, L.E. Latent Class Analysis of Victimization Patterns and Associated Protective Factors among LGBTQ Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardas, E.J.; Ladd, B.A.; Maheux, A.J.; Choukas-Bradley, S.; Salk, R.H.; Thoma, B.C. Testing the minority stress model across gender identity, race, and ethnicity among, U.S. gender minority adolescents. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 2023, 132, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaraman, L.; Hodes, R.; Richer, A.M. Young Sexual Minority Adolescent Experiences of Self-expression and Isolation on Social Media: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e26207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Vargas, N.; Clark, J.L.; Magaña Álvarez, M.; Nelons, D.A.; Parker, R.G. Social isolation and connectedness as determinants of well-being: Global evidence mapping focused on LGBTQ youth. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevor Project. U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People. 2023. Available online: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2023/# (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Perrin, P.B.; Sutter, M.E.; Trujillo, M.A.; Henry, R.S.; Pugh, M. The minority strengths model: Development and initial path analytic validation in racially/ethnically diverse LGBTQ individuals. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.J.; Feinstein, B.A.; Meanley, S.; Flores, D.D.; Watson, R.J. The Role of LGBTQ Identity Pride in the Associations among Discrimination, Social Support, andDepression in a Sample of LGBTQ Adolescents. Ann. LGBTQ Public Popul. Health 2020, 2, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLSEN; CiPHR; CCRC. Out Online: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth on the Internet; GLSEN: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/Out_Online_Full_Report_2013.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Craig, S.L.; McInroy, L.; McCready, L.T.; Alaggia, R. Media: A Catalyst for Resilience in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth. J. LGBT Youth 2015, 12, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, E.A.; Janulis, P.; Phillips, G., 2nd; Truong, R.; Birkett, M. Multiple Minority Stress and LGBT Community Resilience among Sexual Minority Men. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2018, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Mitchell, K.J.; Palmer, N.A.; Reisner, S.L. Online social support as a buffer against online and offline peer and sexual victimization among, U.S. LGBT and non-LGBT youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2015, 39, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceglarek, P.J.D.; Ward, L.M. A tool for help or harm? How associations between social networking use, social support, and mental health differ for sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Taba, M.; Marino, J.; Lim, M.; Skinner, S. Social Media Use and Health and Well-being of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e38449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, V.P.; Rivers, I.; Vecho, O. Membership experiences in gender-sexuality alliances (GSAs) predict increased hope and attenuate the effects of victimization. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 79, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.D.; Poteat, V.P.; Marx, R.A. Holding the space: Individual- and group-level factors predicting member retention in gender-sexuality alliances. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2023, 10, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosciw, J.G.; Clark, C.M.; Truong, N.L.; Zongrone, A.D. The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools; GLSEN: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/NSCS-2019-Full-Report_0.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Poteat, V.P.; Calzo, J.P.; Sherwood, S.H.; Marx, R.A.; O’Brien, M.D.; Dangora, A.; Salgin, L.; Lipkin, A. Gender-Sexuality Alliance meeting experiences predict weekly variation in hope among LGBTQ+ youth. Child Dev. 2023, 94, e215–e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, V.P.; Calzo, J.P.; Yoshikawa, H. Gay-Straight Alliance Involvement and Youths’ Participation in Civic Engagement, Advocacy, and Awareness-Raising. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 56, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.F.; Wachs, S.; Gámez-Guadix, M. The Role of Perceived Gay-Straight Alliance Social Support in the Longitudinal Association between Homophobic Cyberbullying and LGBTQIA Adolescents’ Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, A. Gay–straight alliance (GSA) members’ engagement with sex education in Canadian high schools. Sex Educ. 2014, 14, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Lee, C.M.; Yang, J.; Al-Shoaibi, A.A.A.; Ganson, K.T.; Testa, A.; Jackson, D.B. Associations between sexual orientation and early adolescent screen use: Findings from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2023, 82, 54–58.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillig, T.K.; Murphy, S.T. Fostering Support for LGBTQ Youth? The Effects of A Gay Adolescent Media Portrayal on Young Viewers. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Selkie, E.; Adkins, V.; Masters, E.; Bajpai, A.; Shumer, D. Transgender Adolescents’ Uses of Social Media for Social Support. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, P.; Robards, B.; Hanckel, B.; Vivienne, S.; Churchill, B. “Hey, I’m having these experiences”: Tumblr use and young people’s queer (dis)connections. Int. J. Commun. 2019, 13, 2239–2259. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X.; Fisher, C. Associations Among Web-Based Civic Engagement and Discrimination, Web-Based Social Support, and Mental Health and Substance Use Risk Among LGBT Youth: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e46604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInroy, L.B.; McCloskey, R.J.; Craig, S.L.; Eaton, A.D. LGBTQ+ youths’ community engagement and resource-seeking online versus offline. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2019, 37, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.L.; Eaton, A.D.; McInroy, L.B.; Leung, V.W.; Krishnan, S. Can Social Media Participation Enhance LGBTQ+ Youth Well-Being? Development of the Social Media Benefits Scale. Soc. Media Soc. 2021, 7, 2056305121988931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaraman, L.; Lynch, A.D.; Richer, A.M.; Grossman, J.M. Associations of early social media initiation on digital behaviors and the moderating role of limiting use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, J.M.; Charmaraman, L.; Schaefer, H.S. Conceptualizing the role of racial–ethnic identity in, U.S. adolescent social technology use and well-being. Trans. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2023, 9, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results from Two Population-Based Studies. Res. Aging 2004, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Truong, N.L.; Clark, C.M.; Rosenbach, S.; Kosciw, J.G. The GSA Study: Results of National Surveys about Students’ and Advisors’ Experiences in Gender and Sexuality Alliance Clubs; GLSEN: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.glsen.org/gsa-study (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Inagaki, T.K.; Bryne Haltom, K.E.; Suzuki, S.; Jevtic, I.; Hornstein, E.; Bower, J.E.; Eisenberger, N.I. The Neurobiology of Giving Versus Receiving Support: The Role of Stress-Related and Social Reward-Related Neural Activity. Psychosom. Med. 2016, 78, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; Zuckerman, A.; Kessler, R.C. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevor Project. LGBTQ Young People of Color in Online Spaces. 19 July 2023. Available online: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/lgbtq-young-people-of-color-in-online-spaces-jul-2023/ (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Map of Countries That Criminalise LGBT People. Human Dignity Trust. Available online: https://www.humandignitytrust.org/lgbt-the-law/map-of-criminalisation/?type_filter_submitted=&type_filter%5B%5D=crim_lgbt (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Brown, A. ‘Sometimes people kill you emotionally’: Policing inclusion, experiences of self-identified homosexual youth in secondary schools in Namibia. Afr. Identities 2017, 15, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezza, F.; Mezzalira, S.; Pizzo, R.; Maldonato, N.M.; Bochicchio, V.; Scandurra, C. Minority stress and mental health in European transgender and gender diverse people: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 107, 102358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, F.; Scandurra, C.; Mezzalira, S.; Bochicchio, V.; Salerno, M.; Di Mase, R.; Capalbo, D. Unmet Needs of Pediatricians in Transgender-Specific Care: Results of a Short-Term Training. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M. Perspectives of LGBTQ Youth and Pediatricians in the Primary Care Setting: A Systematic Review. J. Prim. Care Commun. Health 2021, 12, 21501327211044357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDanal, R.; Schleider, J.L.; Fox, K.R.; Eaton, N.R. Loneliness in Gender-Diverse and Sexual Orientation-Diverse Adolescents: Measurement Invariance Analyses and Between-Group Comparisons. Assessment 2023, 30, 706–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Participants |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Value, range | 10–17 |

| Value, mean (SD) | 13.09 (1.52) |

| Gender n (%) | |

| Female | 515 (53.26) |

| Male | 437 (45.19) |

| Other | 15 (1.55) |

| Sexual minority (yes; n = 837 with known sexual orientation), n (%) | 253 (26.16) |

| Not sure or questioning | 119 (47.04) |

| Attracted to both sexes | 75 (29.64) |

| Not attracted to either sex | 13 (5.14) |

| Attracted to the same sex | 22 (8.7) |

| Other | 24 (9.49) |

| Grade n (%) | |

| Sixth | 239 (24.72) |

| Seventh | 204 (21.1) |

| Eighth | 224 (23.16) |

| Ninth | 155 (16.03) |

| Tenth | 144 (14.89) |

| Missing Information | 1 (0.1) |

| Race or ethnicity n (%) | |

| White | 499 (51.6) |

| Black | 81 (8.38) |

| Hispanic | 157 (16.24) |

| Asian | 55 (5.69) |

| Native American | 41 (4.24) |

| Biracial | 63 (6.51) |

| Middle Eastern | 30 (3.1) |

| Other | 38 (3.93) |

| Missing Information | 3 (0.31) |

| Free or reduced-price lunch eligibility, n (%) | 386 (39.92) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charmaraman, L.; Zhang, A.; Wang, K.; Chen, B. Sexual Minorities and Loneliness: Exploring Sexuality through Social Media and Gender–Sexuality Alliance (GSA) Supports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030300

Charmaraman L, Zhang A, Wang K, Chen B. Sexual Minorities and Loneliness: Exploring Sexuality through Social Media and Gender–Sexuality Alliance (GSA) Supports. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(3):300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030300

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharmaraman, Linda, Alice Zhang, Kaitlyn Wang, and Becky Chen. 2024. "Sexual Minorities and Loneliness: Exploring Sexuality through Social Media and Gender–Sexuality Alliance (GSA) Supports" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 3: 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030300

APA StyleCharmaraman, L., Zhang, A., Wang, K., & Chen, B. (2024). Sexual Minorities and Loneliness: Exploring Sexuality through Social Media and Gender–Sexuality Alliance (GSA) Supports. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(3), 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030300