The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Palestinian Patients Attending Selected Governmental Hospitals: An Analysis of Hospital Records

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Patients and Setting

2.3. Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Age and Gender

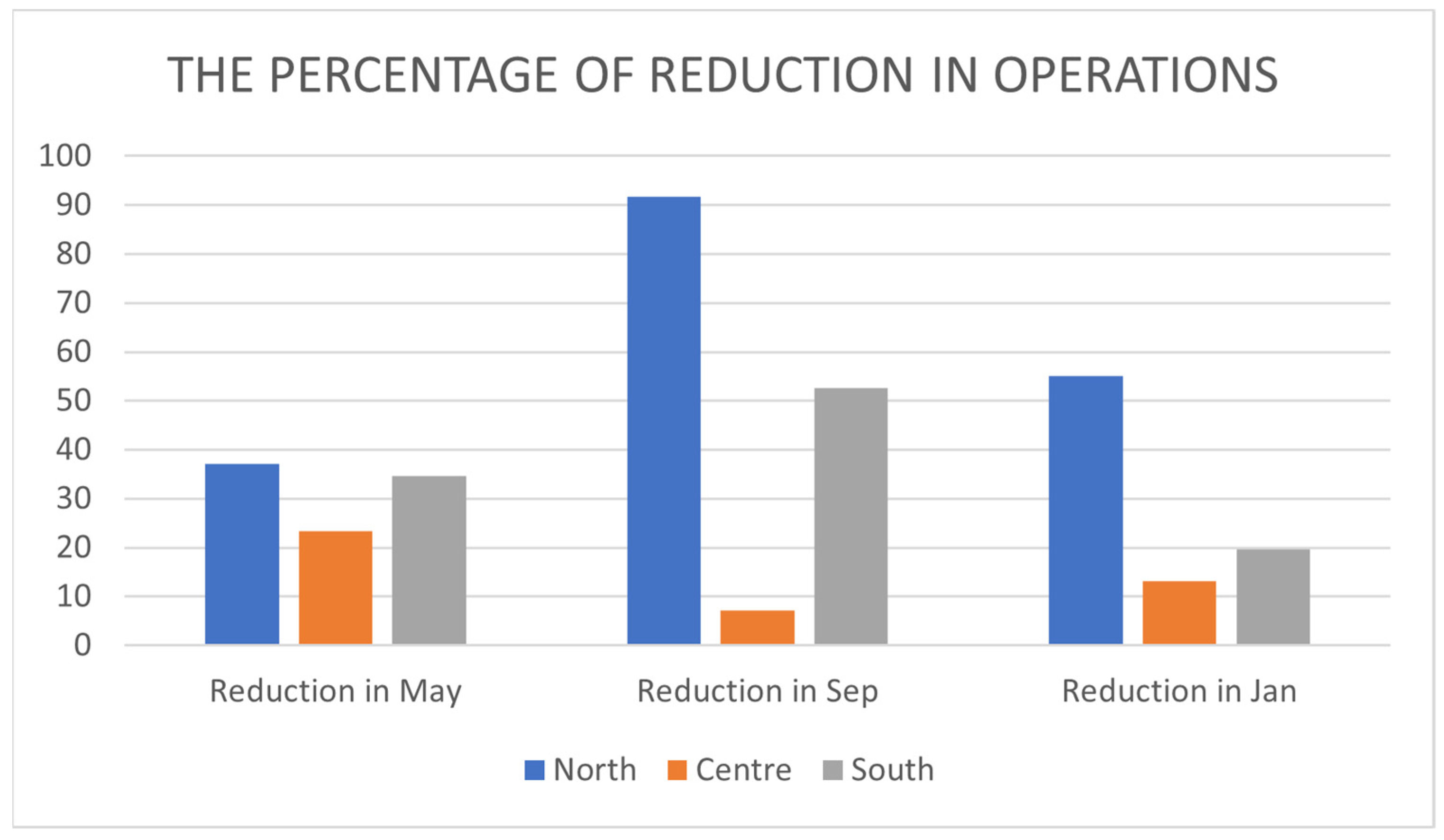

3.2. Number, Type, and Gender Distribution of Operations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Study Strengths and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chanchlani, N.; Buchanan, F.; Gill, P.J. Addressing the indirect effects of COVID-19 on the health of children and young people. CMAJ 2020, 192, E921–E927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJong, C.; Katz, M.H.; Covinsky, K. Deferral of Care for Serious Non–COVID-19 Conditions: A Hidden Harm of COVID-19. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, C.A.; Satchell, L.P.; Fido, D.; Latzman, R.D. Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 19, 1875–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzerini, M.; Barbi, E.; Apicella, A.; Marchetti, F.; Cardinale, F.; Trobia, G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, e10–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantica, G.; Riccardi, N.; Terrone, C.; Gratarola, A. Non-COVID-19 visits to emergency departments during the pandemic: The impact of fear. Public Health 2020, 183, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzia, T.M.; Angelico, R.; Parente, A.; Muiesan, P.; Tisone, G.; Al Alawy, Y.; Arif, A.J.; Attia, M.; Bhati, C.; Battula, R.N.; et al. Global management of a common, underrated surgical task during the COVID-19 pandemic: Gallstone disease—An international survery. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 57, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luizeti, B.O.; Perli, V.A.S.; da Costa, G.G.; Eckert, I.d.C.; Roma, A.M.; da Costa, K.M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical procedures in Brazil: A descriptive study. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prachand, V.N.; Milner, R.; Angelos, P.; Posner, M.C.; Fung, J.J.; Agrawal, N.; Jeevanandam, V.; Matthews, J.B. Medically Necessary, Time-Sensitive Procedures: Scoring System to Ethically and Efficiently Manage Resource Scarcity and Provider Risk During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2020, 231, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabir, A.; Kerwan, A.; Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Khan, M.; Sohrabi, C.; O’Neill, N.; Iosifidis, C.; Griffin, M.; Mathew, G.; et al. Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on surgical practice—Part 1. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 79, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Jiang, F.; Su, W.; Chen, C.; Chen, J.; Mei, W.; Zhan, L.-Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 21, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, K.E.; Brown, K.G.M.; Fisher, O.M.; Steffens, D.; Yeo, D.A.; Koh, C.E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical services: Early experiences at a nominated COVID-19 centre. ANZ J. Surg. 2020, 90, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojoub, A. Corona...Palestinian Lockdown. Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/ar/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A9/%D9%83%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%88%D9%86%D8%A7-%D9%81%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B7%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%AA%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A5%D8%BA%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%82-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%84-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B6%D9%81%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%BA%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A9-5-%D8%A3%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%85/2175024 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Outpatient Clinic Opening Protocol. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/mohps/photos/pcb.2854667007992492/2854666904659169 (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Palestinian Ministry of Health Services Map. Available online: https://site.moh.ps/index/Map/Language/ar (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Health Annual Report, Palestine. Available online: https://site.moh.ps/Content/Books/mv2fIO4XVF1TbERz9cwytaKoWKAsRfslLobNuOmj7OPSAJOw2FvOCI_DQYaIXdf2i8gCmPHbCsav29dIHqW26gZu9qJDiW2QsifZt6FrdS4H2.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Abdulah, D.M.; Abdulla, B.M.O.; Liamputtong, P. Psychological response of children to home confinement during COVID-19: A qualitative arts-based research. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 67, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestinian Ministry of Health, Annual Health Report. Available online: https://site.moh.ps/Content/Books/chup6JkjmKecG8zGx6hnXjILuGecGmPq7Bt4Q4HsFj6vv7tW2W4aGE_ZiCEqSMuZx7v6kHVcDAjC59QDCVuSXx3NmUfwX6Ciqm4OxQrB4xAE6.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Newspaper, A.-A. Palestie Medical Complex (Bee Nest in Changing Times). Available online: https://www.al-ayyam.ps/ar_page.php?id=13d0a9a5y332442021Y13d0a9a5 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Carr, A.; Smith, J.A.; Camaradou, J.; Prieto-Alhambra, D. Growing backlog of planned surgery due to COVID-19. BMJ 2021, 372, n339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shringare, A.; Fernandes, S. COVID-19 Pandemic in India Points to Need for a Decentralized Response. State Local Gov. Rev. 2020, 52, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsi, G.; Seidenari, A.; Diglio, J.; Bellussi, F.; Pilu, G.; Bellussi, F. Obstetrics and gynecology emergency services during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Population Fund. The Impact of COVID-19 on Sexual and Reproductive, Including Maternal Health in Palestine. Available online: https://www.un.org/unispal/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/HEALTCLUSTERRPT_170420.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- United Nations Population Fund. Sexual & Reproductive Health. Available online: https://palestine.unfpa.org/en/node/22582 (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Ralli, M.; Mannelli, G.; Bonali, M.; Capasso, P.; Guarino, P.; Iannini, V.; Mevio, N.; Russo, G.; Scarpa, A.; Spinato, G. Impact of COVID-19 on otolaryngology in Italy: A commentary from the COVID-19 task force of the Young Otolaryngologists of the Italian Society of Otolaryngology. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 7516–7518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kurtzman, J.T.; Moran, G.W.; Anderson, C.B.; McKiernan, J.M. A novel and successful model for redeploying urologists to establish a closed intensive care unit within the emergency department during the COVID-19 crisis. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 901–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahim, H.F.A.; Wick, L.; Halileh, S.; Hassan-Bitar, S.; Chekir, H.; Watt, G.; Khawaja, M. Maternal and child health in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet 2009, 373, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, R.; Althabe, M.; Krynski, M.; Montonati, M.; Pilan, M.L.; Desocio, B.; Moreno, G.; Salgado, G.; Cornelis, J.; Lenz, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a pediatric cardiovascular surgery program of a public hospital from Argentina. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2021, 119, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- GPnotebook. Grades of Complexity of Surgery (Classification According to NICE). Available online: https://gpnotebook.com/simplepage.cfm?ID=x20160504175310544321 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Al-Jabir, A.; Kerwan, A.; Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Khan, M.; Sohrabi, C.; O’Neill, N.; Iosifidis, C.; Griffin, M.; Mathew, G.; et al. Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on surgical practice—Part 2 (surgical prioritisation). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 79, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atary, M.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.E. Deferral of elective surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on Palestinian patients: A cross-sectional study. Confl. Health 2023, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name of hospital | Rafedia | Palestine Medical Complex | Alia |

| Location | North | Center | South |

| Number of beds | 201 | 279 | 252 |

| Allocated COVID-19 beds during waves | 50 | 118 | 98 |

| Number of beds in the COVID-19 hospital in the same governorate | 66 | 26 | 77 |

| Date or outpatient clinic reopening | October 2020 | June 2020, partial closure in September 2020–March 2021 | October 2020 |

| Hospital | Rafedia | PMC | Alia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Period | Mean | Std. Deviation | p-Value * | Mean | Std. Deviation | p-Value * | Mean | Std. Deviation | p-Value * |

| No. of operations per period | Pandemic periods | 132.3 | 93.19 | 0.017 | 316.0 | 88.50 | 0.487 | 214.7 | 26.08 | 0.017 |

| Previous periods | 346.3 | 10.69 | 366.3 | 71.70 | 342.0 | 50.03 | ||||

| Total | 239.3 | 131.37 | 341.2 | 77.14 | 278.3 | 78.34 | ||||

| Type of operations per period | Pandemic periods | 107.3 | 76.79 | 0.020 | 232.0 | 61.49 | 0.307 | 181.3 | 26.31 | 0.026 |

| Previous periods | 278.0 | 18.19 | 282.7 | 42.91 | 294.3 | 50.16 | ||||

| Total | 192.7 | 105.97 | 257.3 | 54.95 | 237.8 | 71.51 | ||||

| No. of female patients in operations | Pandemic periods | 84.3 | 64.81 | 0.030 | 167.7 | 37.75 | 0.208 | 122.7 | 5.13 | 0.012 |

| Previous periods | 210.3 | 12.70 | 212.3 | 35.23 | 189.0 | 25.53 | ||||

| Total | 147.3 | 80.67 | 190.0 | 40.81 | 155.8 | 39.89 | ||||

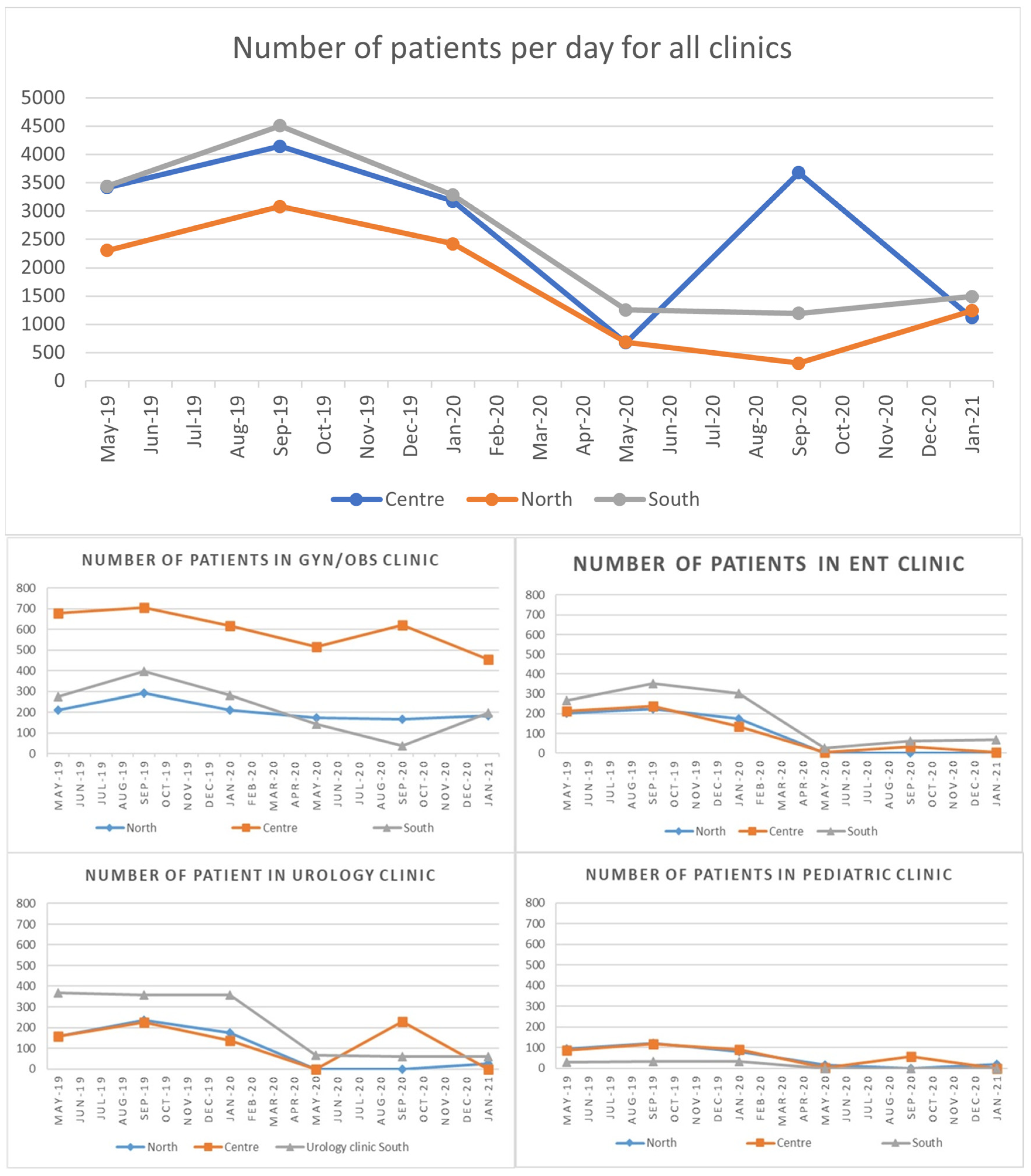

| No. of patients per day in all outpatient clinics | Pandemic periods | 745.7 | 466.37 | 0.007 | 1823.3 | 1620.53 | 0.148 | 1312.7 | 156.87 | 0.004 |

| Previous periods | 2603.7 | 418.50 | 3578.0 | 503.45 | 3742.3 | 665.88 | ||||

| Total | 1674.7 | 1092.11 | 2700.7 | 1440.66 | 2527.5 | 1399.35 | ||||

| No. of female patients in all clinics | Pandemic periods | 62.7 | 10.65 | 0.154 | 72.8 | 13.74 | 0.229 | 53.9 | 4.21 | 0.642 |

| Previous periods | 51.8 | 1.33 | 61.5 | 0.53 | 55.1 | 0.21 | ||||

| Total | 57.3 | 9.04 | 67.2 | 10.66 | 54.5 | 2.75 | ||||

| Average age of patients in all clinics | Pandemic periods | 37.8 | 1.33 | 0.352 | 34.1 | 2.33 | 0.049 | 38.0 | 3.06 | 0.227 |

| Previous periods | 38.7 | 0.38 | 37.9 | 0.56 | 35.4 | 0.57 | ||||

| Total | 38.3 | 0.99 | 36.0 | 2.60 | 36.7 | 2.42 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atary, M.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.E. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Palestinian Patients Attending Selected Governmental Hospitals: An Analysis of Hospital Records. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020196

Atary M, Abu-Rmeileh NME. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Palestinian Patients Attending Selected Governmental Hospitals: An Analysis of Hospital Records. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(2):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020196

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtary, Mousa, and Niveen M. E. Abu-Rmeileh. 2024. "The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Palestinian Patients Attending Selected Governmental Hospitals: An Analysis of Hospital Records" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 2: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020196

APA StyleAtary, M., & Abu-Rmeileh, N. M. E. (2024). The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Palestinian Patients Attending Selected Governmental Hospitals: An Analysis of Hospital Records. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(2), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020196