An Examination of Underlying Domains in Childhood Adversity: A Scoping Review of Studies Conducting Factor Analyses on Adverse Childhood Experiences

Abstract

1. An Examination of the Underlying Domains in Childhood Adversity: A Scoping Review of Studies That Have Conducted Factor Analyses on Adverse Childhood Experiences

1.1. Events Assessed

1.2. Models of Risk

1.3. The Current Study

- To provide researchers and policymakers with a list of adversity measurement tools that have undergone factor analysis, along with sample characteristics and reported factor structures, to assist them with selecting a tool that meets their measurement needs. We expect this will be a helpful resource considering the myriad available tools, measurement methods, and conceptual models represented in the current literature.

- To explore trends in underlying factor structures that may further clarify how the construct of “early life adversity” emerges across studies. We expect this will be useful for those looking to test conceptual models of adversity in future research. It is anticipated our analysis will be complicated by the inconsistent definitions of what constitutes the measurement of adversity, the problem of cross-sample validation in factor analysis, as well as the diversity of research interests discovered (e.g., relating adversity to health outcomes, to economic hardships, to neuroendocrine functioning, etc.).

2. Method

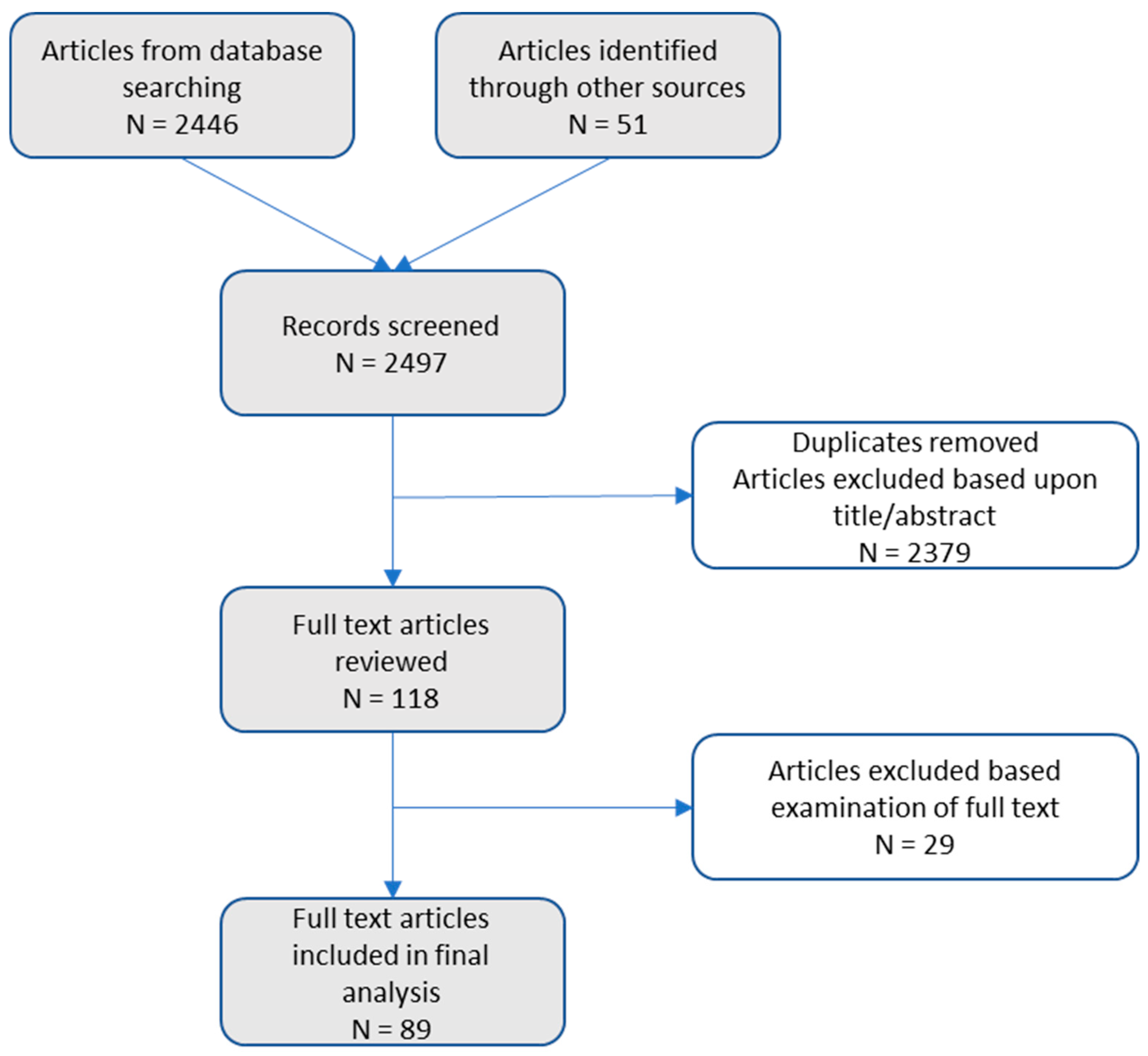

2.1. Search and Identification of Studies

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Events Investigated

3.3. Sexual Abuse

3.4. Neglect (Physical and Emotional) and Financial Hardship/Poverty

3.5. Physical Abuse

3.6. Emotional Abuse

3.7. Household Dysfunction (Parental Stress and Absence)

3.8. Other Notable Adversities

3.9. Conceptual Models Tested

3.10. Positive Childhood Experiences

4. Discussion

4.1. Common Approaches to Early Life Adversity Measurement

4.2. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

4.3. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey

4.4. Retrospective Versus Prospective Measurement

4.5. Conceptual Models

4.6. Neglect

4.7. Considering Sexual Abuse

4.8. Household Dysfunction

5. Future Research

5.1. Conceptualizing Positive Childhood Experiences

5.2. Disentangling Neglect and Financial Hardship/Poverty

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, M.; Soares, S.; Abrahamyan, A.; Severo, M.; Fraga, S. Patterns of childhood adversity and health outcomes in early adolescence: Results from the Generation XXI cohort. Prev. Med. 2023, 171, 107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrick, M.T.; Ford, D.C.; Ports, K.A.; Guinn, A.S. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011-2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Ford, K.; Ramos Rodriguez, G.; Sethi, D.; Passmore, J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e517–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.D.; Solloway, M.R.; Guinosso, S.; Hassink, S.; Srivastav, A.; Ford, D.; Simpson, L.A. Prioritizing possibilities for child and family health: An agenda to address adverse childhood experiences and foster the social and emotional roots of well-being in pediatrics. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S36–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center on the Developing Child. The Impact of Early Adversity on Child Development (InBrief). 2007. Available online: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-the-impact-of-early-adversity-on-childrens-development/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Rith-Najarian, L.R.; Triplett, N.S.; Weisz, J.R.; McLaughlin, K.A. Identifying intervention strategies for preventing the mental health consequences of childhood adversity: A modified Delphi study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 33, 748–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Mersky, J.P.; Janczewski, C.E.; Lee, C.T.P.; Davies, W.H.; Lang, A.C. Validity of an expanded assessment of adverse childhood experiences: A replication study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 117, 105216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, P.; Maguire-Jack, K.; Lombardi, B.; Frey, J.; Rose, R.A. Adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes: Comparing cumulative risk and latent class approaches. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.N.; Swedo, E.A.; Clayton, H.B.; Niolon, P.H.; Shelby, D.; Harrison, K.M. Building infrastructure for surveillance of adverse and positive childhood experiences: Integrated, multimethod approaches to generate data for prevention action. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 62, S31–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronholm, P.F.; Forke, C.M.; Wade, R.; Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Davis, M.; Harkins-Schwarz, M.; Pachter, L.M.; Fein, J.A. Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatekin, C.; Hill, M. Expanding the original definition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2019, 12, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meraj, N.; Arbeau, K.; Fadiya, B.; Ketelaars, T.; St Pierre, J.; Swart, G.T.; Zayed, R. Introducing the Adverse Life Events Inventory for Children (ALEIC): An examination of adverse experiences and related impacts in a large clinical sample of children and youth. Traumatology 2023, 29, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A.C.; Van Hooff, M. Impact of childhood exposure to a natural disaster on adult mental health: 20-year longitudinal follow-up study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Kuendig, J.; Prasad, K.; Sexter, A. Exposure to racism and other adverse childhood experiences among perinatal women with moderate to severe mental illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opaas, M.; Varvin, S. Relationships of childhood adverse experiences with mental health and quality of life at treatment start for adult refugees traumatized by pre-flight experiences of war and human rights violations. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015, 203, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Terry, J. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on mental disorders in young adulthood: Latent classes and community violence exposure. Prev. Med. 2020, 134, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanski, J. Bullying is an adverse childhood experience. J. Health Sci. Educ. 2019, 3, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Li, D.; Whipple, S.S. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 1342–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 840, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartier, M.J.; Walker, J.R.; Naimark, B. Separate and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences in predicting adult health and health care utilization. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liming, K.W.; Brook, J.; Akin, B. Cumulative adverse childhood experiences among children in foster care and the association with reunification: A survival analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2021, 113, 104899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Sheridan, M.A. Beyond cumulative risk: A dimensional approach to childhood adversity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 25, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Pollak, S.D. Rethinking concepts and categories for understanding the neurodevelopmental effects of childhood adversity. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, R.E.; Minnis, H. Practitioner review: Twenty years of research with adverse childhood experience scores–advantages, disadvantages and applications to practice. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Sheridan, M.A.; Humphreys, K.L.; Belsky, J.; Ellis, B.J. The value of dimensional models of early experience: Thinking clearly about concepts and categories. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.; Wright, L.; Finegold, K.E. The effects of early life adversity on children’s mental health and cognitive functioning. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.L.; Jerman, P.; Boparai, S.K.P.; Koita, K.; Briner, S.; Bucci, M.; Harris, N.B. Review of tools for measuring exposure to adversity in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2018, 32, 564–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, K.M.; Stillerman, A.J.; Chandrasekar, L.; Went, N.S.; Niebuhr, D.W. Recommendations for population-based applications of the adverse childhood experiences study: Position statement by the American College of Preventive Medicine. AJPM Focus 2022, 1, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, R.S.; Dempsey, M.T.; Overstreet, S. Conceptualizing exposure to community violence: An application of confirmatory factor analysis. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2003, 18, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Wetzel, A. Factor analysis: A means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2020, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, London, UK, 13–14 May 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, G.W.K.; Bressington, D.; Karatzias, T.; Chien, W.T.; Inoue, S.; Yang, P.J.; Chan, A.C.Y.; Hyland, P. Patterns of exposure to adverse childhood experiences and their associations with mental health: A survey of 1346 university students in East Asia. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloba, O.; Opakunle, T.; Ogunrinu, O. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF): Dimensionality, validity, reliability and gender invariance among Nigerian adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 101, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Ahluvalia, T.; Pogge, D.; Handelsman, L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Stein, J.A.; Newcomb, M.D.; Walker, E.; Pogge, D.; Ahluvalia, T.; Stokes, J.; Handelsman, L.; Medrano, M.; Desmond, D.; et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003, 27, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charak, R.; Koot, H.M. Abuse and neglect in adolescents of Jammu, India: The role of gender, family structure, and parental education. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charak, R.; De Jong, J.T.V.M.; Berckmoes, L.H.; Ndayisaba, H.; Reis, R. Assessing the factor structure of the childhood trauma questionnaire, and cumulative effect of abuse and neglect on mental health among adolescents in conflict-affected Burundi. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 72, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daalder, A.L.; Bogaerts, S. Measuring childhood abuse and neglect in a group of female indoor sex workers in the Netherlands: A confirmatory factor analysis of the Dutch version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form. Psychol. Rep. 2011, 108, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovran, A.; Winje, D.; Øverland, S.N.; Breivik, K.; Arefjord, K.; Dalsbø, A.S.; Jentoft, M.B.; Hansen, A.L.; Waage, L. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in high-risk groups. Scand. J. Psychol. 2013, 54, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudeck, M.; Vasic, N.; Otte, S.; Streb, J.; Wingenfeld, K.; Grabe, H.J.; Freyberger, H.J.; Schroder, T.; Von Schonfeld, C.E.; Driessen, M.; et al. Factorial validity of the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ—SF) in German psychiatric patients, inmates, and university students. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 116, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, D.R.; Baron, S.W.; Scher, C.D.; Stein, M.B. Factor structure and reliability of the childhood trauma questionnaire and prevalence estimates of trauma for male and female street youth. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 27, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi-Oliveira, R.; Cogo-Moreira, H.; Salum, G.A.; Brietzke, E.; Viola, T.W.; Manfro, G.G.; Kristensen, C.H.; Arteche, A.X. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) in Brazilian samples of different age groups: Findings from confirmatory factor analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güleç, M.Y.; Altintaş, M.; İnanç, L.; Bezgin, Ç.H.; Koca, E.K.; Güleç, H. Effects of childhood trauma on somatization in major depressive disorder: The role of alexithymia. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 146, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhong, X.; Gao, Y.; Xiong, G.; Yao, S. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF) among undergraduates and depressive patients. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 91, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.; Gallardo-Pujol, D.; Pereda, N.; Arntz, A.; Bernstein, D.P.; Gaviria, A.M.; Labad, A.; Valero, J.; Gutiérrez-Zotes, J.A. Initial validation of the Spanish Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form: Factor structure, reliability and association with parenting. J. Interpers. Violence 2013, 28, 1498–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karos, K.; Niederstrasser, N.; Abidi, L.; Bernstein, D.P.; Bader, K. Factor structure, reliability, and known groups validity of the German version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Short-Form) in Swiss patients and nonpatients. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2014, 23, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongerslev, M.T.; Bach, B.; Rossi, G.; Trauelsen, A.M.; Ladegaard, N.; Løkkegaard, S.S.; Bo, S. Psychometric validation of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF) in a Danish clinical sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 94, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, M.; Hori, H.; Itoh, M.; Lin, M.; Kawanishi, H.; Narita, M.; Kim, Y. Validation of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form in Japanese clinical and nonclinical adults. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paivio, S.C.; Cramer, K.M. Factor structure and reliability of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in a Canadian undergraduate student sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2004, 28, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrikova, M.; Kascakova, N.; Furstova, J.; Hasto, J.; Tavel, P. Validation and adaptation of the Slovak version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scher, C.D.; Stein, M.B.; Asmundson, G.J.; McCreary, D.R.; Forde, D.R. The childhood trauma questionnaire in a community sample: Psychometric properties and normative data. J. Trauma. Stress 2001, 14, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.; Schmidt, C.O.; Appel, K.; Mahler, J.; Spitzer, C.; Wingenfeld, K.; Barnow, S.; Driessen, M.; Freyberger, H.J.; Volzke, H.; et al. Psychometric functioning, socio-demographic variability of childhood maltreatment in the general population and its effects of depression. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 23, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinhoven, P.; Penninx, B.W.; Hickendorff, M.; van Hemert, A.M.; Bernstein, D.P.; Elzinga, B.M. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: Factor structure, measurement invariance, and validity across emotional disorders. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombs, B.D.; Lewis, C.; Bernstein, D.P.; Medrano, M.A.; Hatch, J.P. An evaluation of the measurement equivalence of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form across gender and race in a sample of drug-abusing adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 63, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombs, B.D.; Bernstein, D.P.; Lobbestael, J.; Arntz, A. A validation study of the Dutch Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form: Factor structure, reliability, and known-groups validity. Child Abuse Negl. 2009, 33, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.D.; Asmundson, G.J.; McCreary, D.R.; Scher, C.; Hami, S.; Stein, M.B. Factorial validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in men and women. Depress. Anxiety 2001, 13, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.H.; Chow, A.; Wang, L.L.; Yu, J.H.; Dai, Y.F.; Lu, X.; Good, M.J.D.; Good, B.J.; Xiao, Z.P. Childhood maltreatment profile in a clinical population in China: A further analysis with existing data of an epidemiologic survey. Compr. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lundgren, K.; Gerdner, A.; Lundqvist, L.O. Childhood abuse and neglect in severely dependent female addicts: Homogeneity and reliability of a Swedish version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2002, 11, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdner, A.; Allgulander, C. Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form (CTQ-SF). Nord. J. Psychiatry 2009, 63, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, C.L.; Cleland, C.; Rosenblum, A.; Fong, C.; Nuttbrock, L.; Marthol, M.; Wallace, J. Psychometric utility of the childhood trauma questionnaire with female street-based sex workers. J. Trauma Dissociation 2004, 5, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrusi, B.; Nakhaee, N. Validity and reliability of a Persian version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Psychol. Rep. 2009, 104, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.; Aas, M.; Klungsøyr, O.; Agartz, I.; Mork, E.; Steen, N.E.; Barrett, E.A.; Lagerberg, T.V.; Rossberg, J.I.; Melle, I.; et al. Patterns of childhood adverse events are associated with clinical characteristics of bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuttler, H.; Schwendemann, H.; Bitzer, E.M. Familial risk and protective factors in alcohol intoxicated adolescents: Psychometric evaluation of the family domain of the Communities That Care Youth Survey (CTC) and a new short version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innamorati, M.; Erbuto, D.; Venturini, P.; Fagioli, F.; Ricci, F.; Lester, D.; Amore, M.; Girardi, P.; Pompili, M. Factorial validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in Italian psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 245, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hock, R.S.; Bryce, C.P.; Waber, D.P.; McCuskee, S.; Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Henderson, D.C.; Galler, J.R. Relationship between infant malnutrition and childhood maltreatment in a Barbados lifespan cohort. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2017, 12, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, G.; Kidd, M.; Seedat, S. A factor analytic study of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form in an all-female South African sample with and without HIV infection. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 92, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.; Slack, K.S. Exploring the relationship between childhood adversity and adult depression: A risk versus strengths-oriented approach. Child Abuse Negl. 2021, 120, 105207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afifi, T.O.; Ford, D.; Gershoff, E.T.; Merrick, M.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Ports, K.A.; MacMillan, H.L.; Holden, G.W.; Taylor, C.A.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 71, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Salmon, S.; Davila, I.G.; Stewart-Tufescu, A.; Fortier, J.; Struck, S.; Asmundson, G.J.G.; Sareen, J.; MacMillan, H.L. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), peer victimization, and substance use among adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 106, 104504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini-Tehrani, M.; Nasiri, M.; Jalali, T.; Sadeghi, R.; Mehrmanesh, M.; Zamanian, H. Relational adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: Development and retrospective validation among young Iranian people. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 5306–5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, Z.; Konstantakopoulos, G.; Tzinieri-Coccosis, M.; Sinodino, C. Rates of childhood trauma in a sample of university students in Greece: The Greece version of the Early Trauma Inventory–Self Report. Psychiatriki 2017, 28, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bailey, H.N.; DeOliveira, C.A.; Wolfe, V.V.; Evans, E.M.; Hartwick, C. The impact of childhood maltreatment history on parenting: A comparison of maltreatment types and assessment methods. Child Abuse Negl. 2012, 36, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.; Blackwell, C.K.; Gombojav, N.; Davis, M.B.; Bruner, C.; Garner, A.S. Toward measurement for a whole child health policy: Validity and national and state prevalence of the Integrated Child Risk Index. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 22, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, A.; Moran, P.M.; Baines, R.; Bunn, A.; Stanford, K. Exploring psychological abuse in childhood: II. Association with other abuse and adult clinical depression. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2002, 66, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremner, J.D.; Bolus, R.; Mayer, E.A. Psychometric properties of the early trauma inventory–self report. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieant, A.; Vannucci, A.; Nakua, H.; Harris, J.; Lovell, J.; Brundavanam, D.; Tottenham, N.; Gee, D.G. Characterizing the dimensional structure of early-life adversity in the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2022, 61, 101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumley, L.D.; Brumley, B.P.; Jaffee, S.R. Comparing cumulative index and factor analytic approaches to measuring maltreatment in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 87, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chegeni, M.; Haghdoost, A.; Shahrbabaki, M.E.; Shahrbabaki, P.M.; Nakhaee, N. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Abuse Short Form. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Cline, H.; Jones, K.G.; Kulkarni-Rajasekhara, S.; Polonsky, H.M.; Vartanian, K.B. Identifying underlying constructs of childhood adversity in a low-income population. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collings, S.J.; Valjee, S.R.; Penning, S.L. Development and preliminary validation of a screen for interpersonal childhood trauma experiences among school-going youth in Durban, South Africa. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2013, 25, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, C.A.; Lewin, A. Development and psychometric properties of the ACE-I: Measuring adverse childhood experiences among Latino immigrant youth. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro, S.L.; Cleary, S.D.; Wan, C.R.; Broussard, B.; Chapman, C.; Haggard, P.J.; Neely, S.J.; Myers, N.L.; Compton, M.T. Measuring trauma and stressful events in childhood and adolescence among patients with first-episode psychosis: Initial factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Trauma Experiences Checklist. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D.C.; Merrick, M.T.; Parks, S.E.; Breiding, M.J.; Gilbert, L.K.; Edwards, V.J.; Dhingra, S.S.; Barile, J.P.; Thompson, W.W. Examination of the factorial structure of adverse childhood experiences and recommendations for three subscale scores. Psychol. Violence 2014, 4, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacaman, R.; Shannon, H.S.; Saab, H.; Arya, N.; Boyce, W. Individual and collective exposure to political violence: Palestinian adolescents coping with conflict. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Vazquez, A.I.; Mosquera-Barral, D.; Leeds, A.M.; Santed-German, M.A. Initial validation of an instrument to evaluate early trauma: The EARLY Scale. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2019, 3, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.G.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Berglund, P.A.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörberg, N.; Kouros, I.; Ekselius, L.; Cunningham, J.; Willebrand, M.; Ramklint, M. Early Trauma Inventory Self-Report Short Form (ETISR-SF): Validation of the Swedish translation in clinical and non-clinical samples. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2019, 73, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iob, E.; Baldwin, J.R.; Plomin, R.; Steptoe, A. Adverse childhood experiences, daytime salivary cortisol, and depressive symptoms in early adulthood: A longitudinal genetically informed twin study. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishfaq, N.; Kamal, A. Explaining the predictive relationship between early life trauma and comorbid psychiatric symptoms among convicts in Pakistan. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2022, 37, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.R.; Lee, E.H.; Lee, S.W.; Jeong, E.G.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, D.; Jeon, H.J. The Early Trauma Inventory Self Report-Short Form: Psychometric properties of the Korean version. Psychiatry Investig. 2012, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidman, R.; Smith, D.; Piccolo, L.R.; Kohler, H.P. Psychometric evaluation of the adverse childhood experience international questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in Malawian adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 92, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, S.M.; Cho, J.; Oshri, A. The influence of childhood adversity on rural black men’s sexual risk behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2016, 50, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristjansson, S.; McCutcheon, V.V.; Agrawal, A.; Lynskey, M.T.; Conroy, E.; Statham, D.J.; Madden, P.A.F.; Henders, A.K.; Todorov, A.A.; Bucholz, K.K.; et al. The variance shared across forms of childhood trauma is strongly associated with liability for psychiatric and substance use disorders. Brain Behav. 2016, 6, e00432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlois, S.; Zern, A.; Kelley, M.E.; Compton, M.T. Adversity in childhood/adolescence and premorbid tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use among first-episode psychosis patients. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Kiely, K.M.; Anstey, K.J. Cumulative risk, factor analysis, and latent class analysis of childhood adversity data in a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2022, 125, 105486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Mejia-Lancheros, C.; Lachaud, J.; Latimer, E.; Aubry, T.; Somers, J.; Distasio, J.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Hwang, S.W. Overall and gender-specific associations between dimensions of adverse childhood experiences and mental health outcomes among homeless adults. Can. J. Psychiatry 2021, 66, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbestael, J.; Arntz, A.; Harkema-Schouten, P.; Bernstein, D. Development and psychometric evaluation of a new assessment method for childhood maltreatment experiences: The interview for traumatic events in childhood (ITEC). Child Abuse Negl. 2009, 33, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggiora Vergano, C.; Lauriola, M.; Speranza, A.M. The Complex Trauma Questionnaire (ComplexTQ): Development and preliminary psychometric properties of an instrument for measuring early relational trauma. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Revington, N.; Seedat, S. The 39-item Child Exposure to Community Violence (CECV) Scale: Exploratory factor analysis and relationship to PTSD symptomatology in trauma-exposed children and adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2013, 20, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinck, F.; Murray, A.L.; Dunne, M.P.; Schmidt, P.; Nikolaidis, G. Factor structure and internal consistency of the ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool Parent Version (ICAST-P) in a cross-country pooled data set in nine Balkan countries. Child Abuse Negl. 2021, 115, 105007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinck, F.; Cosma, A.P.; Mikton, C.; Baban, A. Psychometric properties of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Abuse Short Form (ACE-ASF) among Romanian high school students. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 72, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersky, J.P.; Janczewski, C.E.; Topitzes, J. Rethinking the measurement of adversity: Moving toward second-generation research on adverse childhood experiences. Child Maltreatment 2017, 22, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, M.I.; Schulz, M.S.; Nevarez, M.D.; Preacher, K.J.; Waldinger, R.J. Assessing within-and between-family variations in an expanded measure of childhood adversity. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osório, F.L.; Salum, G.A.; Donadon, M.F.; Forni-dos-Santos, L.; Loureiro, S.R.; Crippa, J.A.S. Psychometrics properties of Early Trauma Inventory Self Report–Short Form (ETISR-SR) for the Brazilian context. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, M.B.; Serrano-Lomelin, J.A.; Amjad, S.; Hicks, A.; Giesbrecht, G.F. Latent factors of adverse childhood experiences and adult-onset asthma. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2021, 12, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatmand, F.; Harrison, R.; Bronson, J.; Dearfield, C.; Crouse, D.; Douglas, M.; Maxwell, C. Violence exposure, drug use and HIV/AIDS risk taking behaviors: The role of gender. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2020, 112, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlechter, P.; Fritz, J.; Cassels, M.; Neufeld, S.A.; Wilkinson, P.O. The Youth and Childhood Adversity Scale: A step towards developing a new measure of adversity and its severity. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1981573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, B.G.; Burke, N.J.; Weems, C.F.; Hellman, J.L.; Carrión, V.G. The interrelation of adverse childhood experiences within an at-risk pediatric sample. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2013, 6, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, D.W.; Rojo-Wissar, D.M.; Smail, E.J.; Musci, R.J.; Wilcox, H.C.; Johnson, S.B. Expanding on threat and deprivation: Empirical examination of adversity dimensions and psychiatric outcomes among emerging adults. Emerg. Adulthood 2023, 11, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swingen, J.K. Psychometric Developments of the ACE-IQ: Understanding the Trauma History of Latine Immigrants. Doctoral Dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6187/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Thompson, R.; Proctor, L.J.; Weisbart, C.; Lewis, T.L.; English, D.J.; Hussey, J.M.; Runyan, D.K. (2007). Children’s self-reports about violence exposure: An examination of the Things I Have Seen and Heard Scale. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2007, 77, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, H.; Bell, J.F.; Induni, M. Community-level adverse experiences and emotional regulation in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 42, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usacheva, M.; Choe, D.; Liu, S.; Timmer, S.; Belsky, J. Testing the empirical integration of threat-deprivation and harshness-unpredictability dimensional models of adversity. Dev. Psychopathol. 2022, 34, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo-Medina, P.; Pineda-Marín, C.; Soler, F.; Saaverdra-Roa, A.; Ortega, L.A. Validation of the Early Trauma Inventory Self Report-Short Form and trauma prevalence in Colombia. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2021, 13, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vederhus, J.K.; Timko, C.; Haugland, S.H. Adverse childhood experiences and impact on quality of life in adulthood: Development and validation of a short difficult childhood questionnaire in a large population-based health survey. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, B.E.; Conrad, J.K.; Wilburn, V.G.; Ramamonjiarivelo, Z.; Gladden, J. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health conditions among multiracial adolescents. Ethn. Health 2021, 27, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Krueger, K.R.; Arnold, S.E.; Barnes, L.L.; de Leon, C.F.M.; Bienias, J.L.; Bennett, D.A. Childhood adversity and psychosocial adjustment in old age. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Fink, L.; Handelsman, L.; Foote, J.; Lovejoy, M.; Wenzel, K.; Sapareto, E.; Ruggiero, J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgieva, S.; Tomás, J.M.; Navarro-Pérez, J.J.; Samper-García, P. Systematic review and critical appraisal of five of the most recurrently validated child maltreatment assessment instruments from 2010 to 2020. Trauma Violence Abuse 2023, 24, 2448–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Józsa, K.; Morgan, G.A. Reversed items in Likert scales: Filtering out invalid responders. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. 2017, 25, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, P.G. Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 66, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, S.; Tomas, J.M.; Navarro-Pérez, J.J. Systematic review and critical appraisal of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form (CTQ-SF). Child Abuse Negl. 2021, 120, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, S.; Hall, T.; Constable, L.; Paton, K.; Sanci, L.; Goldfeld, S.; Hiscock, H. Screening for adverse childhood experiences in children: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021051884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Porter, L.E.; Brown, D.W. Inside the adverse childhood experience score: Strengths, limitations, and misapplications. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iragorri, N.; Spackman, E. Assessing the value of screening tools: Reviewing the challenges and opportunities of cost-effectiveness analysis. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cassis, T.; D’Arcy, C.; Low, N.; Meng, X. Development and validation of a brief form of the Childhood Adversities Questionnaire among a population of mood disorders. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP2288–NP2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardt, J.; Rutter, M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, K.; Rossen, E.; Koriakin, T.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Resnick, C. A systematic review of trauma screening measures for children and adolescents. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2018, 33, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.L. Comparison of parent and child reports on child maltreatment in a representative household sample in Hong Kong. J. Fam. Violence 2012, 27, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tingberg, B.; Bredlov, B.; Ygge, B.M. Nurses’ experience in clinical encounters with children experiencing abuse and their parents. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 2718–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M.; Tutty, L.M.; McConnell, S.; Barter, K.; Fairholm, J. What Canadian youth tell us about disclosing abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2009, 33, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, F.W.; Amaya-Jackson, L.; Putnam, K.T.; Briggs, E.C. Synergistic adversities and behavioral problems in traumatized children and adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 106, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, M.A.; McLaughlin, K.A. Dimensions of early experience and neural development: Deprivation and threat. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, N.; Larson, K.; Son, J.; Lu, M.; Bethell, C. Income inequality and the differential effect of adverse childhood experiences in US children. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S70–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, D.; McCartney, G.; Smith, M.; Armour, G. Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D. Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children—Past, present, and future perspectives. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 402–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Stein, J.A.; Handelsman, L. Predicting personality pathology among adult patients with substance use disorders: Effects of childhood maltreatment. Addict. Behav. 1998, 23, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Measure(s)/PCE | Sample Size, Age, and Modality of Assessment | Factor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aloba et al. (2020) [39] | CTQ-SF | n = 1337 Adolescent Self-Report | Emotional Abuse Physical Abuse Sexual Abuse Emotional Neglect Physical Neglect |

| Bernstein et al. (1997) [40] | CTQ (70 item) | n = 398 Adolescent Self-Report | |

| Bernstein et al. (1998) [41] | CTQ administered CTQ-SF 25 item scored | n = 339 Adult Retrospective | |

| Charak and Koot (2014) [42] | CTQ-SF | n = 702 Adolescent Self-Report | |

| Charak et al. (2017) [43] | CTQ-SF (French adaptation, translated to Kirundi. 25 item) | n = 231 Adolescent Self-Report and Adult Retrospective | |

| Daalder and Bogaerts (2011) [44] | CTQ-SF (Dutch version) | n = 123 Adult Retrospective | |

| Dovran et al. (2013) [45] | CTQ-SF (Norwegian version) | n = 445 n = 517 Adolescent Self-Report and Adult Retrospective | |

| Dudeck et al. (2015) [46] | CTQ-SF (German version) | n = 1524 n = 224 Adult Retrospective | |

| Forde et al. (2012) [47] | CTQ-SF | n = 397 Adolescent Self-Report | |

| Grassi-Oliveira et al. (2014) [48] | CTQ-SF (Brazilian version) | n = 1925 Adolescent Self-Report and Adult Retrospective | |

| Güleç et al. (2013) [49] | CTQ-SF | n = 150 Adult Retrospective | |

| He et al. (2019) [50] | CTQ-SF (Chinese version) | n = 3431 n = 234 Adult Retrospective | |

| Hernandez et al. (2013) [51] | CTQ-SF (Spanish version) | n = 185 Adult Retrospective | |

| Karos et al. (2014) [52] | CTQ-SF (German version) | n = 661 Adult Retrospective | |

| Kongerslev at al., (2019) [53] | CTQ-SF (Danish version) | n = 393 Adolescent Self-Report and Adult Retrospective | |

| Nakajima et al. (2022) [54] | CTQ-SF (Japanese version) | n = 762 n = 111 Adult Retrospective | |

| Paivio and Cramer (2004) [55] | CTQ | n = 470 Adult Retrospective | |

| Petrikova et al. (2021) [56] | CTQ-SF (Slovak version) | n = 1018 Adult Retrospective | |

| Scher et al. (2001) [57] | CTQ-SF | n = 1007 Adult Retrospective | |

| Schulz et al. (2014) [58] | CTQ-SF (German version) | n = 2265 Adult Retrospective | |

| Spinhoven et al. (2014) [59] | CTQ-SF | n = 2308 Adult Retrospective | |

| Thombs et al. (2007) [60] | CTQ-SF | n = 693 Adult Retrospective | |

| Thombs et al. (2009) [61] | CTQ-SF (Dutch version) | n = 261 n = 227 Adult Retrospective | |

| Wright et al. (2001) (Men) [62] | CTQ-SF | n= 916 Adult Retrospective | |

| Zhang et al. (2013) [63] | CTQ-SF | n = 2090 Adult Retrospective | |

| Lundgren et al. (2002) [64] | CTQ (Swedish version, 53 item) | n = 55 Adult Retrospective | Emotional/Physical Abuse Sexual Abuse Emotional Neglect Physical Neglect Factor 1 Factor 2 |

| Scher et al. (2001) [57] | CTQ-SF | n = 1007 Adult Retrospective | Emotional and Physical Neglect Sexual Abuse Emotional Abuse and Physical Neglect Physical Abuse |

| Gerdner and Allgulander (2009) [65] | CTQ-SF (Swedish version) | n = 659 Adult Retrospective | Emotional Abuse Emotional Neglect Physical Abuse Sexual Abuse |

| Villano et al. (2004) [66] | CTQ-SF | n = 171 Adult Retrospective | |

| Garrusi and Nakhaee (2009) [67] | CTQ-SF (Persian version) | n = 1000 Adult Retrospective | Emotional/Physical Abuse Sexual Abuse Emotional Neglect Physical Neglect |

| Lundgren et al. (2002) [64] | CTQ (Swedish version, 53 item) | n = 55 Adult Retrospective | |

| Wright et al. (2001) (Women) [62] | CTQ-SF | n = 916 Adult Retrospective | |

| Larsson et al. (2013) [68] | CTQ-SF (Norwegian version) | n = 141 Adult Retrospective | Emotional Abuse/Neglect-Revised Sexual Abuse-Revised Physical Abuse-Revised |

| Kuttler et al. (2015) [69] | CTQ-SF (six-item short version) | n = 342 Adolescent Self-Report | Physical Abuse Emotional Abuse Emotional Neglect |

| Innamorati et al. (2016) [70] | CTQ-SF (Italian version) | n = 471 Adult Retrospective | Emotional Neglect/Abuse Sexual Abuse Physical Neglect/Abuse |

| Hock et al. (2017) [71] | CTQ-SF | n = 139 Adult Retrospective | Emotional/Physical Abuse Sexual Abuse Emotional/Physical Neglect |

| Spies et al. (2019) [72] | CTQ-SF | n = 314 Adult Retrospective |

| Article | Measure(s) | Sample Size, Age, and Modality of Assessment | Factor(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott and Slack, (2021) [73] | Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale (Abbreviated by authors—8 Items) Childhood Caregiving Environment scale | n = 618 Adult Retrospective | Unnamed Factor 1 Unnamed Factor 2 | |

| Afifi et al. (2017) [74] | Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale (ACE-10) | n = 8316 Adult Retrospective | Physical/Emotional Abuse | |

| Afifi et al. (2020) [75] | ACE-10 Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire | n = 2002 Adolescent (Self and Caregiver Report) | Child Maltreatment and Peer Victimization Household Challenges | |

| Amini-Tehrani et al. (2021) [76] | Relational Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire | n = 487 Adult Retrospective | Adverse parent/caregiver–child relationship Adverse parent–parent relationship Adverse school relationships Sexual abuse | |

| Antonopoulou et al. (2017) [77] | Early Trauma Inventory Self-Report Short Form (ETI-SR-SF) (Greek version) | n = 605 Adult Retrospective | Unnamed Factor | |

| Bailey et al. (2012) [78] | History of Maltreatment and Trauma Form | n = 90 Adult Retrospective and Child (Caregiver Report) | Neglect and emotional maltreatment Sexual abuse Physical abuse Witnessing family violence | |

| Bethell et al. (2021) [79] | NSCH (National Survey of Children’s Health)-ACEs | n = 95,677 Child (Caregiver Report) | Overall adversity | |

| Bifulco et al. (2002) [80] | Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA) | n = 204 Adult Retrospective | Care Control | |

| Bremner et al. (2007) [81] | Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report (ETI-SR) | n = 288 Adult Retrospective | ETI General Trauma Factor 1 General Trauma Factor 2 Physical Abuse Factor 1 Physical Abuse Factor 2 Emotional Abuse Sexual Abuse | ETI(SF) General Trauma Random Events Dysfunctional Family Family Accidents Physical Abuse Factor 1 Physical Abuse Factor 2 Emotional Abuse |

| Brieant et al. (2022) [82] | NSCH (National Survey of Children’s Health)-ACEs | n = 7115 Child (Self and Caregiver Report) | Caregiver psychopathology Socioeconomic disadvantage and neighborhood safety Secondary caregiver lack of support Primary caregiver lack of support Youth report of family conflict Caregiver substance use and separation from biological parent Family anger arguments Family aggression Trauma exposure Lack of supervision | |

| Brumley et al. (2019) [83] | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (6 items) | n = 27,088 Adult Retrospective | Unnamed Factor 1 Unnamed Factor 2 | |

| Chegeni et al. (2020) [84] | Adverse Childhood Experiences Abuse Short Form (ACE-ASF)—Persian version | n = 494 Adult Retrospective | Physical-emotional abuse Sexual abuse | |

| Choi et al. 2020 [10] | Childhood Experiences Survey (CES) | n = 2413 Adult Retrospective | ACE-10: Child Maltreatment Household dysfunction | CES: Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 |

| Cohen-Cline et al. (2019) [85] | Unnamed measure | n = 9176 Adult Retrospective | Instability Inadequate emotional support | |

| Collings et al. (2013) [86] | Developmental Trauma Inventory (DTI) | n = 720 Adolescent (Self Report) | Emotional abuse Domestic neglect Poverty Witnessing domestic violence Witnessing community violence Community assault Indecent assault Rape Domestic assault Domestic injury | |

| Conway and Lewin, (2022) [87] | ACE-Immigration (ACE-I) | n = 338 Adolescent (Self Report) | Unrest/Violence in Home Country Dangerous Journey Immigration instability | |

| Cristofaro, (2013) [88] | Trauma Experience Checklist (TEC) | n = 205 Adult Retrospective | Interpersonal abuse and family stress Violence, death and legal involvement | |

| Ford et al. (2014) [89] | Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (ACE module) | n = 85,248 Adult Retrospective | Household dysfunction Physical/emotional abuse Sexual abuse | |

| Giacaman et al. (2007) [90] | Unnamed measure | n = 3415 Adolescent (Self Report) | Individual: Home Personal | Collective: Strangers Friends/neighbors Tear gas/sound bombs Shelling/shooting/explosions |

| Gonzalez-Vazquez et al. (2019) [91] | EARLY Scale | n = 522 Adult Retrospective | Early-FP: Positive experiences Early-FN: Emotional neglect Overprotection Physical abuse Witnessing problems Role reversal High demand Emotional abuse | |

| Green et al. (2010) [92] | National Co-morbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) 12 adversity items | n = 9282 Adult Retrospective | Maladaptive Family functioning Other childhood adversities: Unnamed factor 1 Unnamed factor 2 | |

| Hörberg et al. (2019) [93] | Early Trauma Inventory-SR—Short form (ETISR-SF) Swedish translation | n = 299 Adolescent (Self Report) | General trauma Physical abuse Emotional abuse Sexual abuse | |

| Iob et al. (2021) [94] | Unnamed composite measure | n = 300 Child (Caregiver Report) | Negative parental experiences Divorce/separation Bullying Abuse | |

| Ishfaq and Kamal (2020) [95] | Early Trauma Inventory-SR Short Form (ETISR-SF) Urdu translation | n = 479 Adult Retrospective | Physical abuse Emotional abuse Sexual abuse | |

| Jeon et al. (2012) [96] | Early Trauma Inventory Self Report-Short Form (ETISR-SF) Korean translation | n = 304 Adult Retrospective | General trauma Physical abuse Emotional abuse Sexual abuse | |

| Karatekin and Hill (2019) [14] | “Expanded ACES” Items from Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ) and ACEs scale | n = 4179 Adult Retrospective | Child maltreatment Household dysfunction Community dysfunction Peer dysfunction/property victimization | |

| Kidman et al. (2019) [97] | ACE International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) | n = 410 Adolescent (Self Report) | Household disruption Abuse Neglect | |

| Kogan et al. (2016) [98] | Adverse Childhood Events Scale (11 items) | n = 505 Adult Retrospective | Abusive Parenting Neglect Witnessing Maternal Abuse | |

| Kristjansson et al. (2016) [99] | Christchurch Trauma Assessment Neglect Scale (Modified) | n = 2594 Adult Retrospective | Childhood physical abuse Childhood sexual abuse Parental partner abuse | |

| Landis et al. (2003) [34] | Things I Have Seen and Heard Scale | n = 242 Child (Self Report) | Model 1: Witnessing Victimization | Model 2: Indirect factor Traumatic factor Abuse factor |

| Langlois et al. (2021) [100] | Original Composite Measure | n = 247 Adult Retrospective | Violence and environmental adversity Interpersonal abuse Neglect and lack of connectedness | |

| Lian et al. (2022) [101] | Personality and Total Health (PATH) Through Life Project | n = 210 Adult Retrospective | Threat Deprivation | |

| Liu et al. (2021) [102] | Interview for Traumatic Events in Childhood (ITEC) | n = 2235 Adult Retrospective | Maltreatment Sexual abuse Neglect Divorce Household Dysfunction | |

| Lobbestael et al. (2009) [103] | Interview for Traumatic Events in Childhood (ITEC) | n = 579 Adult Retrospective | Sexual abuse Physical abuse Emotional abuse Physical neglect Emotional neglect | |

| Maggiora Vergano et al. (2015) [104] | Complex Trauma Questionnaire (ComplexTQ) | n = 229 Adult Retrospective | Mother: Role reversal Physical abuse Psychological abuse/rejection Emotional neglect Failure of protection Material neglect | Father: Emotional neglect Failure of protection Material neglect Psychological abuse/rejection Physical abuse |

| Martin et al. (2013) [105] | Child Exposure to Community Violence Checklist (CECV) | n = 231 Adolescent (Self Report) | Witnessing general violent/criminal acts Directly experiencing and witnessing both family and non-family violence and threats of physical harm Directly experiencing non-family sexual abuse and general feelings of unsafety | |

| Meinck et al. (2021) [106] | International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN) Child Abuse Screening Tool Parent Version (ICAST-P) | n = 25,202 Child (Caregiver Report) | General Factor Physical violence Psychological violence Neglect Sexual violence | |

| Meinck et al. (2017) [107] | Adverse Childhood Experiences—Abuse Short Form (ACE-ASF) | n = 1668 Adolescent (Caregiver Report) | Physical/emotional abuse Sexual abuse | |

| Mersky et al. (2017) [108] | Childhood Experiences Survey (CES) ACE-10 ACE-17 | n = 1241 Adult Retrospective | 10 item model: Child maltreatment Household dysfunction | 16 item model: Unnamed factor 1 Unnamed factor 2 Unnamed factor 3 Unnamed factor 4 |

| Morrill et al. (2019) [109] | Unnamed composite measure | n = 1194 Adult Retrospective | Chaotic families Stressful environment Poor family–environment fit | |

| Osório et al. (2013) [110] | Early Trauma Inventory Self Report (ETISR-SR)—Short Form Portuguese translation | n = 253 Adult Retrospective | General traumas Physical abuse Emotional abuse Sexual abuse | |

| Ospina et al. (2021) [111] | Alberta ACE survey | n = 1207 Adult Retrospective | Relational Violence Negative home environment Illness at home Sexual abuse | |

| Saadatmand et al. (2020) [112] | Unnamed measure | n = 440 Adult Retrospective | Having witnessed violence Childhood sexual abuse Personal attacks Witnessing violence amongst adults Direct violence from peers and adults Having witnessed murder | |

| Schlechter et al. (2021) [113] | Youth and Childhood Adversity Scale (YCAS) Childhood Traumatic Events Scale | n = 1047 Adult Retrospective | Unnamed factor | |

| Scott et al. (2013) [114] | ACE-10 | n = 184 Child and Adolescent (Chart Review) | Abuse Household Dysfunction Mixed | |

| Sosnowski et al. (2022) [115] | Unnamed composite measure | n = 1662 Adolescent (Self Report) | Threat—non-betrayal Emotional deprivation Sexual assault Threat—Betrayal | |

| Swingen (2020) [116] | ACE-IQ—Spanish Translation | n = 184 Adult Retrospective | Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 | |

| Thompson et al. (2007) [117] | Things I Have Seen and Heard Scale | n = 784 Child (Self Report) | Community Violence Domestic Violence | |

| Thurston et al. (2018) [118] | ACE-10 | n = 65,680 Child (Caregiver Report) and Adult Retrospective | Household Community | |

| Usacheva et al. (2022) [119] | Unnamed composite measure | n = 5000 Child (Self and Caregiver Report) | Threat Unpredictability Deprivation | |

| Vallejo-Medina et al. (2021) [120] | Early Trauma Inventory Self Report-Short Form | n = 2080 Adult Retrospective | General Physical Emotional Sexual | |

| Vederhus et al. (2021) [121] | Difficult Childhood Questionnaire (DCQ) | n = 28,074 Adult Retrospective | Unnamed Factor | |

| Weller et al. (2021) [122] | NSCH (National Survey of Children’s Health)-ACEs | n = 1231 Adolescent (Self-Report) | Unnamed Factor | |

| Wilson et al. (2006) [123] | Unnamed composite measure | n = 235 Adult Retrospective | Emotional neglect Parental intimidation Parental violence Family turmoil Financial need | |

| Study Category | Age and Modality of Assessment a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Retrospective | Adolescent Self-Report | Adolescent Caregiver Report | Child Caregiver Report | Child Self Report | Child and Adolescent Chart Review | |

| Non-CTQ | 36 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 1 |

| CTQ | 32 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 68 | 18 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 1 |

| Study Category | Sample Size a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <100 | 101–499 | 500–999 | 1000+ | |

| Non-CTQ | 1 | 22 | 6 | 25 |

| CTQ | 2 | 21 | 7 | 11 |

| Total | 3 | 43 | 13 | 36 |

| Factor | # of Studies Loaded as Its Own Factor | # of Studies Combined into Another Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTQ | Non-CTQ | CTQ | Non-CTQ | |

| Sexual Abuse | 34 | 20 | 0 | 23 |

| Physical Neglect | 29 | 1 (4 a) | 6 | 27 |

| Emotional Neglect | 30 | 7 | 5 | 22 |

| Financial hardship/Poverty | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| Physical Abuse | 30 | 14 | 7 | 36 |

| Emotional Abuse | 28 | 3 | 9 | 37 |

| Household Dysfunction | 0 | 33 | 0 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Willoughby, K.; Atallah, S.; Arbeau, K.; Pearce, J.; Ketelaars, T.; St. Pierre, J. An Examination of Underlying Domains in Childhood Adversity: A Scoping Review of Studies Conducting Factor Analyses on Adverse Childhood Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21111441

Willoughby K, Atallah S, Arbeau K, Pearce J, Ketelaars T, St. Pierre J. An Examination of Underlying Domains in Childhood Adversity: A Scoping Review of Studies Conducting Factor Analyses on Adverse Childhood Experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(11):1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21111441

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilloughby, Keith, Serena Atallah, Kim Arbeau, Jenn Pearce, Thomas Ketelaars, and Jeff St. Pierre. 2024. "An Examination of Underlying Domains in Childhood Adversity: A Scoping Review of Studies Conducting Factor Analyses on Adverse Childhood Experiences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 11: 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21111441

APA StyleWilloughby, K., Atallah, S., Arbeau, K., Pearce, J., Ketelaars, T., & St. Pierre, J. (2024). An Examination of Underlying Domains in Childhood Adversity: A Scoping Review of Studies Conducting Factor Analyses on Adverse Childhood Experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(11), 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21111441