Abstract

Background: Cancer is the leading cause of death in Canada and a major cause of death worldwide. Environmental exposure to carcinogens and environments that may relate to health behaviors are important to examine as they can be modified to lower cancer risks. Built environments include aspects such as transit infrastructure, greenspace, food and tobacco environments, or land use, which may impact how people move, exercise, eat, and live. While environments may play a role in overall cancer risk, exposure to carcinogens or healthier environments is not equitably spread across space. Exposures to carcinogens commonly concentrate among socially and/or economically disadvantaged populations. While many studies have examined inequalities in exposure or cancer risk, this has commonly been for one exposure. Methods: This scoping review collected and synthesized research that examines inequities in carcinogenic environments and exposures. Results: This scoping review found that neighborhoods with higher proportions of low-income residents, racialized people, or same-sex couples had higher exposures to carcinogens and environments that may influence cancer risk. There are currently four main themes in research studying inequitable exposures: air pollution and hazardous substances, tobacco access, food access, and other aspects of the built environment, with most research still focusing on air pollution. Conclusions: More work is needed to understand how exposures to these four areas intersect with other factors to reduce inequities in exposures to support longer-term goals toward cancer prevention.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a major cause of death worldwide, which resulted in approximately 10 million deaths in 2020 [1]. In Canada, cancer is the leading cause of death, and cancer incidence and deaths are increasing as the population ages [2,3]. In 2022, an estimated 233,900 new cancer cases and 85,100 cancer deaths were expected in Canada [4]. In addition to the burden of illness, cancer care is costly, amounting to approximately 7.5 billion CAD in 2012 in Canada, over double the costs from 2005 [5]. There are also many indirect costs associated with cancer, including out-of-pocket costs, loss of earnings, and time costs. In total, the direct and indirect costs of cancer in 2021 in Canada were estimated at 26.2 billion CAD, with approximately one-third of this being borne by patients and their families [6]. These significant human health and economic impacts make cancer control a significant public health issue.

Environmental carcinogen exposure is an important cancer risk factor that can be modified. In Europe, an estimated 3.6% of lung cancers are due to air pollution exposure each year [7]; in Ontario, Canada, an estimated 5.8% of lung cancers are due to air pollution (PM2.5 and diesel particulate matter) [8]. When considering the most prevalent environmental carcinogen exposures in Ontario (solar ultraviolet radiation, radon, arsenic, acrylamide, asbestos, and select others), an estimated 3540–6510 cancers could have been prevented each year by controlling these exposures [8]. In addition, the built environment including aspects such as spatial proximity, transit infrastructure, greenspace, and land use can shape cancer risk by impacting how people move, exercise, eat, and live [9].

Importantly, exposure to environmental carcinogens is not evenly distributed across populations creating environmental inequity. Exposures are concentrated among socially and/or economically disadvantaged populations who may be especially vulnerable to hazardous exposures due to limited resources at the individual and community level [10]. For example, higher exposures to hazardous air pollutants have been observed in areas with greater concentrations of low-income and marginalized communities, including racialized people (Asian and Black) [11,12,13,14], same-sex male partner households [15], and isolated immigrants [16]. Disproportionate exposures among equity-deserving communities have also been observed for non-air-pollutant-related hazards, including water contaminants such as lead [17,18], lack of greenspace [19,20], and poor walkability scores [21,22].

Social demographics such as income, education, unemployment, housing conditions, and the neighborhood can play an integral role in several behavioral risk factors such as diet, physical activity and obesity, or substance use such as smoking and alcohol consumption [23,24,25,26], which are inherently related to certain types of cancer [27]. In the United States, over one-third of cancer deaths are attributed to diet, lack of physical activity, and obesity while another third relates to exposure to tobacco products [27]. Furthermore, in Europe, lower educational attainment is related to higher smoking rates, as well as lower physical activity levels and consumption of fruits and vegetables [28]. Sexual and gender minorities have been found to have higher smoking rates compared to their heterosexual counterparts in Canada and the United States [29], as well as increased risk factors for other types of cancers [30]. For example, an increased risk of anal cancer has been found among gay men, who are at increased risk of human papilloma virus infections of the anus, and an increased risk of breast and gynecological cancers has been noted among lesbian women, possibly due to fewer pregnancies and children, higher body mass indices, and less exercise, among other factors [31]. Social demographics may play a role in both higher carcinogen exposures and higher behavioral risk factors, increasing the odds of cancer for residents living in these environments.

The scope of environmental justice and environmental equality research is vast. Although previous reviews have investigated inequitable exposures via specific routes of exposure (e.g., indoor air pollution [32] and outdoor air pollution [33]), none, to our knowledge, have focused on carcinogenic exposures more broadly. CAREX (Carcinogen Exposure) Canada is a program of research that evaluates occupational and environmental carcinogen exposures in Canada by drawing on publicly available data sources [34]. Current estimates of environmental exposures include maps of predicted levels of specific carcinogens in Canada, as well as estimates of lifetime excess cancer risk [35]. These present a broad picture of Canadians’ general environmental exposures and do not capture the inequitable distribution of exposures across the social determinants of health. Thus, the objective of this scoping review was to collect and synthesize research that examines inequities in environmental exposures to carcinogens or environments that relate to cancer behavioral risk factors, relevant to the Canadian context. The overall goal of this inquiry is to support the development of new CAREX environmental exposure estimates that are policy-actionable from an equity, diversity, and inclusion perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

Search and Selection Strategy

For this scoping review, we searched both PUBMED and SCOPUS for articles on 6 October 2021 with no restrictions for dates. The search terms were environment * AND (inequ * OR dispari *) AND (cancer OR carcinogen). All articles were imported into Covidence, which is online software that streamlines the review process. Inclusion criteria selected for articles written in English, that were not review articles, that examined carcinogen exposure/environment or cancer outcomes not including mortality, that mentioned inequalities or disparities, that were environmental in nature (i.e., not occupational), and that took place in Canada, the United States, New Zealand, Australia, or western Europe. While occupational exposures are undoubtedly an important route of exposure, they were beyond the scope of this review, as the focus was on exposures in the environment.

Two team members (E.R. and K.L.) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts to reduce bias in the selection of articles for inclusion, and any disagreements were resolved by the senior author (C.E.P.). This set of articles was then moved to full-text review in Covidence.

Reasons for excluding a paper during full-text review were the same as the initial inclusion criteria and were noted in Covidence, and any disagreements between the two main reviewers (E.R. and K.L.) were also resolved by a third reviewer (C.E.P.). Papers that made it through this stage were sent for data extraction in Covidence. Data extracted included study location, objective, design, population, and spatial scale. The methods used in the study were also examined with a focus on the data sources for both carcinogenic exposure and inequalities/disparities, as well as analytical methods. We also summarized the results, including sample size and observed cancer disparities/inequalities.

The extracted data were then summarized into more concise tables to identify themes and findings more easily. Summary values were calculated to describe the body of literature with regard to the exposures, inequalities, and outcomes examined.

3. Results

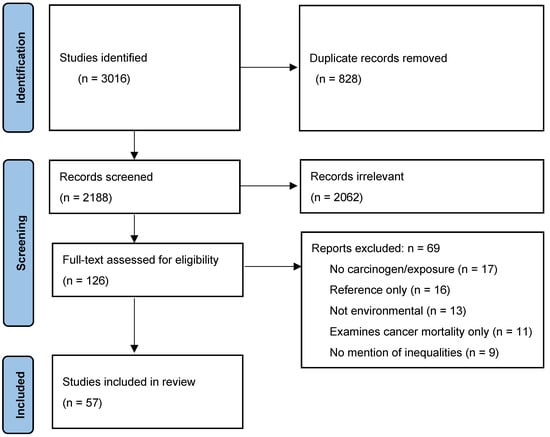

In total, 3016 papers were identified by the literature search strategy. After the removal of duplicates, a total of 2188 articles remained for title and abstract screening. Overall, the reviewers disagreed on the inclusion of 137 papers (agreement rate: 94%) and with the support of the third reviewer, consensus was reached on the included studies.

After the title and abstract review, a total of 126 papers were included in full-text review during which they were assessed in more detail on the basis of the aforementioned inclusion criteria. A total of 69 papers were excluded (Figure 1). In total, 57 manuscripts were included in the data extraction process and analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram illustrating the article selection process.

Overall, most of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 46), with five from the United Kingdom, three from New Zealand, and one each from Australia, Canada, and France. These studies were conducted at varying spatial scales, with 26 local- or city-based studies, 19 national studies, and 12 regional studies (state, provincial, or multiple study sites). The majority of papers (n = 37) examined some aspect of air pollution (hazardous air pollution (HAP), particulate matter, diesel engine exhaust, or other air pollution measures). One study examined solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR), one examined nitrate in drinking water, and one study assessed perchloroethylene in buildings with dry-cleaning facilities. In total, 14 studies examined aspects of the built environment, with four studies examining more general aspects of the built environment, while an additional four assessed the food environment, four evaluated the tobacco environment, and two studied access to greenspace.

Data Sources and Approach

To obtain demographic data to assess potential inequalities, the majority of papers relied on census data (n = 44), while eight studies used surveys, and the others used more local health-based studies, which may have included surveys and other measurement methods; one study assessed mortality records. Exposure data came from a variety of sources, with the US EPA’s NATA (National Air Toxics Assessment) being the most common (n = 29). Four studies used data on food outlet location/type (which was typically taken from business directories), four also assessed tobacco retailers’ data (obtained from government tobacco taxation records, national databases, or store types), three modeled air pollution datasets, two used land-use data, two used built environment data, and two used data from the EPA cumulative exposure dataset. The remaining studies used data from one of the following sources: environmental audit of playgrounds, California Air Resources Board health risk assessment, California Cancer Registry, California Neighborhoods Data System, community water system, measurement, National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI), Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), and National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). The analytical approaches of the 57 studies were similar, with a modeling approach (e.g., GEE, OLS, linear, or logistic models) being applied in 48 of the studies. The remaining eight papers applied descriptive analyses, including t-tests, spatial clustering, and chi-squared analysis.

4. What Did the Studies Find?

4.1. Air Pollution and Hazardous Substances

The details for each manuscript were broken into two tables. Table 1 displays all papers related to hazardous air pollution, while Table 2 includes the other studies, which mainly focused on aspects of the built environment including greenspace, along with access to healthy/unhealthy food and tobacco. Results supported the hypothesis that inequalities in carcinogen exposures exist. The majority of studies examined inequalities with respect to socioeconomic status (SES) and/or race/ethnicity. As reported in Table 1, of the 41 studies that examined some form of air pollution or toxic substances, almost all of them found that race/ethnicity and/or SES was significantly related to cancer risk. While exposures and results did vary by race/ethnicity, many studies examined predominantly Black, Hispanic, or Asian neighborhoods, where exposure or lifetime excess cancer risk was frequently higher. Interestingly, two studies examined exposure for same-sex couples, and both reported that same-sex couples had higher exposures to environmental carcinogens or carcinogenic environments [15,36]. Padilla et al. (2004) was the only study that did not report consistent findings between exposure and equity-deserving populations but did report that environmental inequalities related to the urban development and immigration patterns within cities in France [37]. For the one study that examined perchloroethylene exposure, the most important factor related to exposure was having a dry cleaner within the building, and this was consistent regardless of socioeconomic status [38]. Lastly, drinking water had higher nitrate values in predominantly Hispanic neighborhoods versus non-Hispanic areas with community water systems [39].

Table 1.

Summary of studies examining air pollution and hazardous substances.

Table 2.

Summary of papers studying remaining exposures.

4.2. Other Carcinogens or Environmental Cancer Risk Factors

Table 2 summarizes articles examining other known/potential carcinogens or environmental cancer behavioral risk factors including solar UVR exposure, food access, built environment, tobacco environment, and greenspace. For both tobacco and food, access was typically defined by proximity, either by distance to outlets or density, which assesses clustering or the number of outlets. Access to quality foods typically examined how easily residents have access to healthy food (i.e., supermarket or fruit/vegetable stand) and less healthy food such as fast-food restaurants. Greenspace was typically examined with a proximity and density calculation (i.e., distance to or density of parks/open space) but was also sometimes assessed using a vegetation index. Other built environment characteristics examined neighborhood walkability, street connectivity, traffic, sidewalks, or other aspects that may encourage or discourage physical activity. Only one study examined solar UVR exposure via access to shade structures in parks and reported that lower-SES areas had poorer access to shade than their wealthier counterparts [84]. Greater spatial exposure to fast-food restaurants was associated with higher fast-food consumption and odds of obesity [80], especially for those in the lowest income category [80]. Lower-income areas commonly had more exposure to fast-food outlets [81,82]. More general built environment measures (such as walkability and greenspace) reported varying results related to exposures and disparities. For example, one study reported breast cancer risk to be highest for high income neighborhoods, with White women having the highest odds [75], and with adjustments for more urban environment and mixed land uses decreasing the disparities for all Black and Hispanic, but not White neighborhoods. One study reported that SES, along with race/ethnicity, were not related to physical activity levels for youth [78] while, another found that socioeconomic status and some aspects of the built environment were related to obesity [83]. For tobacco environments, the highest exposure tended to occur in predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods [85,87,88] or areas of lower income [86]. Access to greenspace was typically lower for those in lower-SES neighborhoods [74].

5. Discussion

This scoping review found that neighborhoods with higher proportions of low-income residents, racialized people (e.g., Black, Hispanic, Asian), or same-sex couples had higher exposures to carcinogens and environments that may influence cancer risk. This review summarizes the available literature to examine carcinogenic exposure overall, including greenspace, food or tobacco access, solar UVR exposure, perchloroethylene, and other aspects of the built environment. The four general themes related to inequitable carcinogen exposures or environments that may relate to behavioral risk factors for cancer were air pollution and hazardous substances, access to healthy/unhealthy food, access to tobacco outlets, and more general built environment factors (i.e., walkability and access to parks/greenspace). However, the majority of studies assessing inequitable environmental exposures focused on air pollution, with little attention paid to other carcinogenic exposures or environments.

5.1. Air Pollution

Among studies of air pollution and exposure to hazardous substances, lower-income neighborhoods and/or those with a higher proportion of Black and Hispanic people commonly had higher exposures. While Black and Hispanic populations commonly had higher exposure in the United States [43,47,57,64], other countries reported similar findings for racialized populations relevant to their country [14,41]. In New Zealand, for instance, Asian and Māori populations had higher exposure to air pollution than their White counterparts [41]. One exception was reported in France, where inconsistent results were found across the four cities examined (Lille, Lyon, Marseille, and Paris), with some cities reporting evidence of inequities in racialized populations while others did not [37]. This demonstrates how the racial/ethnic and SES makeup of cities along with historical socioeconomics, immigration, and development patterns may impact exposures. For example, in Paris, census blocks with the highest income (or social status) had the highest exposure to nitrogen dioxide [37]. This finding is similar to results reported in Rome, Italy [89]. The authors suggested that these changes in exposures for higher-income areas reflect how development patterns have changed [37]. Air pollution, in some cases, is no longer largely originating from industrial emissions but rather from tail-pipe emissions from traffic, commuting, and movement of goods [37]. In France, larger industrial polluters have moved outside of Paris to other regions of France or even into Eastern Europe or developing countries [37]. Thus, air pollution in central Paris is mainly from transportation sources. On the other hand, in both Lille and Marseille, higher NO2 levels were reported in areas of highest distress (lowest income). Both Lille and Marseille were historically cities with large industrial economies. Currently, Lille has a textile industry, while Marseille has a large port along with steel and petrochemical industries [37]. The more industrial nature of these cities may relate to the higher exposures experienced closer to city cores, which is different from the situation in Paris.

In Paris and Lyon, exposure was highest in the higher-income areas, related to individual choices in which people prefer to live in particular neighborhoods within the city, where the benefits of that location (such as walkability, access to healthy foods or greenspace, etc.) may outweigh the detriment of higher air pollution exposure [37]. For example, many urban areas may have higher traffic-related air pollution, but may also have better access to healthy foods, fewer tobacco outlets, and more walkable neighborhoods with greenspace and parks. The intersectional nature of human and urban development patterns, environmental contamination, and categories of marginalization are important considerations that may vary substantially by region or jurisdiction.

5.2. Greenspace

Two studies examined access to greenspace, an aspect of the built environment, and both found that lower SES areas had poorer access to greenspace [73,74]. This is a common finding across the environmental health literature, with many studies linking lower-income areas with poorer access to parks [90,91,92]. This suggests that cities are being built or perhaps modified in an inequitable manner, allowing for parks and better greenspace in higher-income areas. It is unclear whether parks or greenspaces are being constructed with higher-income communities or being added after the fact, but overall access to greenspace and parks was inequitably distributed. With regard to health outcomes, one study from a review based in New Zealand did not find a relationship between greenspace and any health outcome (cancer or cardiovascular disease) [74], but the United Kingdom study did find a relationship with all-cause mortality [73]. Even though direct links between greenspace and cancer risk were not reported, this is an active area of investigation, and a tentative association has been noted in the broader literature. Greenspace is thought to have several health-promoting benefits [93]. This may relate to escapes from noise and pollution [94], reductions in the urban heat island effect [95], helping with anxiety levels [96] and/or overall mental health [97], improved air quality, and opportunities for physical activity [98]. Overall, the included studies demonstrate that more general interventions at the population level (i.e., changing access to or improving greenspace) will more effectively impact health behaviors than individual-level interventions [73,99]. Thus, a continued examination of the association between greenspace and cancer, and the inequitable access to greenspace will be important moving forward from a cancer prevention and health inequities perspective.

5.3. Access to Food

Inequities, especially related to income, in access to healthy food have been discussed since the early 2000s [100,101,102,103]. The clustering of fast-food outlets (also referred to as food swamps) has also been reported more frequently in equity-deserving neighborhoods [104,105]. Food access can impact cancer risk since diets low in fruits and vegetables and higher in processed foods are known risk factors for several types of cancer; it is also related to obesity and overweight, which are inherent risk factors for several cancers. Studies reviewed in this paper found that inequalities in access to food exist [79,80,81,82], as lower-SES areas commonly had the highest exposure to fast-food restaurants. Furthermore, odds of obesity were also higher for those with low income and the highest fast-food exposure [79,80]. However, evidence in the broader literature regarding the relationship between food environment and dietary consumption is inconclusive at this point, partly due to varying methodologies and issues defining “access” [106], along with cultural and policy-based differences in the various countries examined. Even so, several studies included in this review reported positive associations between fast-food exposure and both fast-food consumption [107,108,109] and body weight [110,111,112]. Thus, when considering environmental cancer risk and potential inequities, healthy food access may be an important piece to consider.

5.4. Access to Tobacco

Similar to the effects of food environments, neighborhoods with a higher density of tobacco outlets may lead to a higher purchasing of cigarettes and other tobacco-related products [113,114] and underage sales [115]. The density of tobacco outlets has also been linked to higher tobacco usage among adolescents, with lower-income neighborhoods having higher odds of smoking [116]. As reported in Table 2, race/ethnicity also played a role in tobacco access, meaning those living in predominantly Black or Hispanic areas were also overexposed, in addition to low-income residents. Tobacco remains the highest modifiable contributor to the risk for many cancers, and public health campaigns over the past several decades have been effective at lowering rates of smoking. Findings from this review suggest that smoking prevention policies should better investigate ways to more effectively reach and support people of lower SES in tobacco use reduction or elimination. It has been reported that longer distances (i.e., lower proximity) to tobacco outlets was an effective method to reduce smoking [117], but the density of outlets or clustering was not a significant factor. This suggests that not having nearby access to tobacco may be beneficial to lower smoking rates, but the feasibility of this as a policy idea is not established.

5.5. Complexities, Challenges, and Future Work

One important aspect to discuss, which is particularly pertinent for studies that examine the built environment, is that the data sources, populations under investigation, and methods are commonly different. Many studies examining access to food, walkability, physical activity, or obesity have produced mixed results, with some studies reporting positive associations, some others reporting negative associations, and some detecting significant relationships [74,75,78,80,82,83,85,86,87,118]. Given the scope of these studies, with many examining different populations, in various countries, the results are not always generalizable to each country, neighborhood, or even city. Furthermore, the methods and data utilized to examine potential relationships are also inconsistent, further complicating interpretation.

One apparently contradictory finding from our review is that White women had higher odds of breast cancer, especially in high-income neighborhoods [75]. Breast cancer epidemiology is complex, and, while there are links reported between environmental chemical exposures and the risk of breast cancer, there are several social factors relating to risk that tend to cluster in wealthier women [119,120]. These include a higher likelihood of remaining childfree, delaying childbirth until older age, use of hormone supplements, and less frequent breastfeeding [121]. Furthermore, certain genetic predispositions may put certain White populations at a higher risk of breast cancer [121]. While higher-income White women may have higher incidence rates for breast cancer, mortality rates are commonly higher among Black women [122], which likely relates to access to primary care and specialist physicians, cancer screening programs, or the type of breast cancer itself [123,124].

An important observation to make is that while we were able to discern four main themes in this scoping review (air pollution, access to foods, access to tobacco, and built environment), it is highly likely that these intersect in complex ways with environmental carcinogen exposures, human behavior, and cultural dynamics, but the topics were typically considered in isolation (i.e., independent of one another). Future work should take a broader approach to examine carcinogen exposures and the complex intersections of environmental contamination, the work people do, wealth and income inequality, racism, and cultural sensitivity. It is important to contextualize carcinogenic exposures in order to gain a better understanding of potential cancer and/or other health risks associated with the environment. This review adds to the literature by looking beyond the individual exposures, but more empirical research is needed to further fill these gaps.

Furthermore, complexities exist in how we define “healthy” environments, as neighborhoods can have, for example, higher exposure to fast food but also good access to parks, greenspace, and walkable streets. Others may have higher air pollution, while other environmental aspects of neighborhoods, such as parks, high-quality food access, or reduced tobacco access, may be protective. This may become a more common occurrence in many cities as pollution becomes more related to transportation (i.e., cars and trucks) than industrial emissions, and more walkable, older neighborhoods may experience more traffic-related air pollution.

One of the limitations of this review was the fact that most studies were completed in the United States and, thus, may not always be generalizable to Canada. While this is a limitation, it also highlights the need for future work to examine inequities in exposures in other countries to gain a better understanding of how exposure varies by country, region, city, or neighborhood. Furthermore, most of the reviewed studies were cross-sectional and ecological in nature with analysis conducted at the census tract level (or similar census boundary).

Findings from this scoping review highlighted that many lower-SES areas or neighborhoods with a higher proportion of racialized people commonly have higher exposures to carcinogens or environments that may influence behavioral risk factors for cancer. In an effort to examine these issues at the national level, as part of the CAREX Canada mandate, our next steps are to update our environmental estimates and knowledge products to summarize neighborhood-level exposures with an equity lens. Our renewed purpose as a result of this work is to generate data-driven knowledge products that can be used by policymakers and advocates to reduce inequities in spatially clustered cancer risk factors in Canada.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review synthesized research examining inequities in environmental exposures to carcinogens. The current literature examining inequitable carcinogenic exposures can be summarized into four main themes: air pollution and hazardous substances, tobacco access, food access, and other aspects of the built environment, although studies examining hazardous air pollutants are by far the most common. Findings from this review highlighted that, while some differences exist, neighborhoods with a higher percentage of lower-income and/or racialized residents typically have higher carcinogen exposures, as well as lower exposure to healthy built environments. Inequities in environmental cancer risk need to be examined and addressed by policymakers to address systemic factors influencing environmental risks related to cancer and other chronic diseases. Steps taken to improve the environment now will support longer-term goals toward cancer prevention.

Author Contributions

K.L., E.R. and C.E.P. contributed to the study conceptualization and design. K.L., E.R. and C.E.P. assisted with the review process. The first draft of the manuscript was written by K.L., while K.L., E.R. and C.E.P. contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

CAREX Canada is primarily funded by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| GEE | Generalized estimating equations |

| HAP | Hazardous air pollution |

| NAAQS | National Ambient Air Quality Standards |

| NATA | National Air Toxics Assessment |

| NPRI | National Pollutant Release Inventory |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| TRI | Toxics Release Inventory |

| UVR | Ultraviolet radiation |

References

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. 2022. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0394-01. Leading Causes of Death, Total Population, by Age Group. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1310039401 (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Xie, L.; Semenciw, R.; Mery, L. Cancer Incidence in Canada: Trends and Projections (1983–2032). Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2015, 35, 2–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.R.; Poirier, A.; Woods, R.R.; Ellison, L.F.; Billette, J.-M.; Demers, A.A.; Zhang, S.X.; Yao, C.; Finley, C.; Fitzgerald, N.; et al. Projected Estimates of Cancer in Canada in 2022. CMAJ 2022, 194, E601–E607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, C.; Phd, M.A.; Weir, S.; Dphil, M.A.; Rangrej, J.; Mmath, M.; Krahn, M.D.; Mittmann, N.; Hoch, J.S.; Chan, K.K.W.; et al. The Economic Burden of Cancer Care in Canada: A Population-Based Cost Study. Can. Med. Assoc. Open Access J. 2018, 6, E1–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaszczuk, R.; Yong, J.H.E.; Sun, Z.; De Oliveira, C. The Economic Burden of Cancer in Canada from a Societal Perspective. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 2735–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffetta, P.; Nyberg, F. Contribution of Environmental Factors to Cancer Risk. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.L.; Greco, S.L.; MacIntyre, E.; MacIntyre, E.; Young, S.; Warden, H.; Drudge, C.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Candido, E.; et al. An Approach to Estimating the Environmental Burden of Cancer from Known and Probable Carcinogens: Application to Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, A.J.D.; Minaker, L.M. Is Cancer Prevention Influenced by the Built Environment? A Multidisciplinary Scoping Review. Cancer 2019, 125, 3299–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruize, H.; Droomers, M.; van Kamp, I.; Ruijsbroek, A. What Causes Environmental Inequalities and Related Health Effects? An Analysis of Evolving Concepts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikati, I.; Benson, A.F.; Luben, T.J.; Sacks, J.D.; Richmond-Bryant, J. Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G.S.; Fox, M.A.; Trush, M.; Kanarek, N.; Glass, T.A.; Curriero, F.C. Differential Exposure to Hazardous Air Pollution in the United States: A Multilevel Analysis of Urbanization and Neighborhood Socioeconomic Deprivation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grineski, S.E.; Collins, T.W.; Morales, D.X. Asian Americans and Disproportionate Exposure to Carcinogenic Hazardous Air Pollutants: A National Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 185, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, S.; Gower, S.; Rinner, C.; Campbell, M. Identifying Inequitable Exposure to Toxic Air Pollution in Racialized and Low-Income Neighbourhoods to Support Pollution Prevention. Geospat. Health 2013, 7, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.W.; Grineski, S.E.; Morales, D.X. Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Environmental Injustice: Unequal Carcinogenic Air Pollution Risks in Greater Houston. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liévanos, R.S. Race, Deprivation, and Immigrant Isolation: The Spatial Demography of Air-Toxic Clusters in the Continental United States. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 54, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delpla, I.; Benmarhnia, T.; Lebel, A.; Levallois, P.; Rodriguez, M.J. Investigating Social Inequalities in Exposure to Drinking Water Contaminants in Rural Areas. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 207, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanphear, B.P.; Hornung, R.; Ho, M.; Howard, C.R.; Eberle, S.; Knauf, K. Environmental Lead Exposure during Early Childhood. J. Pediatr. 2002, 140, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault, L.; Christidis, T.; Toyib, O.; Crouse, D.L. Ethnocultural and Socioeconomic Disparities in Exposure to Residential Greenness within Urban Canada. Health Rep. 2021, 32, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, M.; Zhang, X.; Harris, C.D.; Holt, J.B.; Croft, J.B. Spatial Disparities in the Distribution of Parks and Green Spaces in the USA. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiron, D.; Setton, E.M.; Shairsingh, K.; Brauer, M.; Hystad, P.; Ross, N.A.; Brook, J.R. Healthy Built Environment: Spatial Patterns and Relationships of Multiple Exposures and Deprivation in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 106003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaee, M.; Echeverri, B.; Zuchowicz, Z.; Wiltfang, K.; Lucarelli, J.F. Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities of Sidewalk Quality in a Traditional Rust Belt City. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairouz, S.; Greenfield, T.K. A Comparative Multi-Level Analysis of Contextual Drinking in American and Canadian Adults. Addiction 2007, 102, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.Y.; Myers, A.E.; Isgett, L.F.; Ribisl, K.M. Neighborhood Racial, Ethnic, and Income Disparities in Accessibility to Multiple Tobacco Retailers: Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, 2015. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 17, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoufour, J.D.; de Jonge, E.A.L.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Hofman, A.; Nunn, S.P.T.; Franco, O.H. Socio-Economic Indicators and Diet Quality in an Older Population. Maturitas 2018, 107, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, T.F.; Sheetz, A.; Gurm, R.; Woodward, A.C.; Kline-Rogers, E.; Leibowitz, R.; Durussel-Weston, J.; Palma-Davis, L.; Aaronson, S.; Fitzgerald, C.M.; et al. Understanding Childhood Obesity in America: Linkages between Household Income, Community Resources, and Children’s Behaviors. Am. Heart J. 2012, 163, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushi, L.H.; Byers, T.; Doyle, C.; Bandera, E.v.; McCullough, M.; Gansler, T.; Andrews, K.S.; Thun, M.J. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention: Reducing the Risk of Cancer with Healthy Food Choices and Physical Activity. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2006, 56, 254–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, T.; Gkiouleka, A.; Reibling, N.; Thomson, K.H.; Eikemo, T.A.; Bambra, C. Educational Inequalities in Risky Health Behaviours in 21 European Countries: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014) Special Module on the Social Determinants of Health. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheldon, C.W.; Kaufman, A.R.; Kasza, K.A.; Moser, R.P. Tobacco Use Among Adults by Sexual Orientation: Findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. LGBT Health 2018, 5, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polek, C.; Hardie, T. Cancer Screening and Prevention in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Community and Asian Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Members. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, G.P.; Sanchez, J.A.; Sutton, S.K.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Nguyen, G.T.; Green, B.L.; Kanetsky, P.A.; Schabath, M.B. Cancer and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender/Transsexual, and Queer/Questioning (LGBTQ) Populations. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.; Taylor, J.; Davies, M.; Shrubsole, C.; Symonds, P.; Dimitroulopoulou, S. Exposure to Indoor Air Pollution across Socio-Economic Groups in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review of the Literature and a Modelling Methodology. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Chen, D.; Buzzelli, M.; Aronson, K.J. Environmental Equity Research: Review with Focus on Outdoor Air Pollution Research Methods and Analytic Tools. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2015, 70, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, C.E.; Ge, C.B.; Hall, A.L.; Davies, H.W.; Demers, P.A. CAREX Canada: An Enhanced Model for Assessing Occupational Carcinogen Exposure. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 72, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CAREX Canada Environmental Approach. Available online: https://www.carexcanada.ca/carcinogen-profiles/#environmental-approach (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Collins, T.W.; Grineski, S.E.; Morales, D.X. Environmental Injustice and Sexual Minority Health Disparities: A National Study of Inequitable Health Risks from Air Pollution among Same-Sex Partners. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 191, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, C.M.; Kihal-Talantikite, W.; Vieira, V.M.; Rossello, P.; LeNir, G.; Zmirou-Navier, D.; Deguen, S. Air Quality and Social Deprivation in Four French Metropolitan Areas—A Localized Spatiotemporal Environmental Inequality Analysis. Environ. Res. 2014, 134, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, J.E.; Mazor, K.A.; Shost, S.J.; Serle, J.; Aldous, K.M.; Blount, B.C. Socioeconomic Disparities in Indoor Air, Breath, and Blood Perchloroethylene Level among Adult and Child Residents of Buildings with or without a Dry Cleaner. Environ. Res. 2013, 122, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaider, L.A.; Swetschinski, L.; Campbell, C.; Rudel, R.A. Environmental Justice and Drinking Water Quality: Are There Socioeconomic Disparities in Nitrate Levels in U.S. Drinking Water? Environ. Health 2019, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, J.; Collins, T.W.; Grineski, S.E.; Montgomery, M.C.; Hernandez, M. Comparing Disproportionate Exposure to Acute and Chronic Pollution Risks: A Case Study in Houston, Texas. Risk. Anal. 2014, 34, 2005–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Kingham, S.; Zawar-Reza, P. Every Breath You Take? Environmental Justice and Air Pollution in Christchurch, New Zealand. Environ. Plann. A 2006, 38, 919–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Stuart, A.L. Exposure and Inequality for Select Urban Air Pollutants in the Tampa Bay Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 551–552, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, A.; Hartley, S.; Holder, C. Analysis of Diesel Particulate Matter Health Risk Disparities in Selected US Harbor Areas. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101 (Suppl. S1), S217–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hricko, A.; Rowland, G.; Eckel, S.; Logan, A.; Taher, M.; Wilson, J. Global Trade, Local Impacts: Lessons from California on Health Impacts and Environmental Justice Concerns for Residents Living near Freight Rail Yards. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 1914–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osiecki, K.M.; Kim, S.; Chukwudozie, I.B.; Calhoun, E.A. Utilizing Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis to Examine Health and Environmental Disparities in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods. Environ. Justice 2013, 6, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, W.; Jia, C.; Kedia, S. Uneven Magnitude of Disparities in Cancer Risks from Air Toxics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 4365–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoner, A.M.; Anderson, S.E.; Buckley, T.J. Ambient Air Toxics and Asthma Prevalence among a Representative Sample of US Kindergarten-Age Children. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.; Burwell-Naney, K.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, H.; Samantapudi, A.; Murray, R.; Dalemarre, L.; Rice, L.; Williams, E. Assessment of Sociodemographic and Geographic Disparities in Cancer Risk from Air Toxics in South Carolina. Environ. Res. 2015, 140, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liévanos, R.S. Air-Toxic Clusters Revisited: Intersectional Environmental Inequalities and Indigenous Deprivation in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Regions. Race Soc. Probl. 2019, 11, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, R.; Grineski, S.; Collins, T.; Morales, D.X. Ancestry-Based Intracategorical Injustices in Carcinogenic Air Pollution Exposures in the United States. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 33, 987–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, M., Jr.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Sadd, J.L. The Air Is Always Cleaner on the Other Side: Race, Space, and Ambient Air Toxics Exposures in California. J. Urban Aff. 2005, 27, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grineski, S.E.; Collins, T. Lifetime Cancer Risks from Hazardous Air Pollutants in US Public School Districts. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grineski, S.; Morales, D.X.; Collins, T.; Hernandez, E.; Fuentes, A. The Burden of Carcinogenic Air Toxics among Asian Americans in Four US Metro Areas. Popul. Environ. 2019, 40, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, S.H.; Marko, D.; Sexton, K. Cumulative Cancer Risk from Air Pollution in Houston: Disparities in Risk Burden and Social Disadvantage. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 4312–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; James, W.; Kedia, S. Relationship of Racial Composition and Cancer Risks from Air Toxics Exposure in Memphis, Tennessee, U.S.A. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7713–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello-Frosch, R.; Pastor, M.; Sadd, J. Environmental Justice and Southern California’s “Riskscape” The Distribution of Air Toxics Exposures and Health Risks among Diverse Communities. Urban Aff. Rev. 2001, 36, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello-Frosch, R.; Jesdale, B.M. Separate and Unequal: Residential Segregation and Estimated Cancer Risks Associated with Ambient Air Toxins in U.S. Metropolitan Areas. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.W.; Grineski, S.E.; Chakraborty, J.; McDonald, Y.J. Understanding Environmental Health Inequalities through Comparative Intracategorical Analysis: Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Risks from Air Toxics in El Paso County, Texas. Health Place 2011, 17, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, T.W.; Grineski, S.E.; Chakraborty, J.; Montgomery, M.C.; Hernandez, M. Downscaling Environmental Justice Analysis: Determinants of Household-Level Hazardous Air Pollutant Exposure in Greater Houston. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2015, 105, 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekenga, C.C.; Yeung, C.Y.; Oka, M. Cancer Risk from Air Toxics in Relation to Neighborhood Isolation and Sociodemographic Characteristics: A Spatial Analysis of the St. Louis Metropolitan Area, USA. Environ. Res. 2019, 179, 108844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loustaunau, M.G.; Chakraborty, J. Vehicular Air Pollution in Houston, Texas: An Intra-Categorical Analysis of Environmental Injustice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello-Frosch, R.; Pastor, M., Jr.; Sadd, J. Integrating Environmental Justice and the Precautionary Principle in Research and Policy Making: The Case of Ambient Air Toxics Exposures and Health Risks among Schoolchildren in Los Angeles. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 2002, 584, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apelberg, B.J.; Buckley, T.J.; White, R.H. Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities in Cancer Risk from Air Toxics in Maryland. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.H.; Evans, C.R. Intersectional Environmental Justice and Population Health Inequalities: A Novel Approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 269, 113559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, J. Automobiles, Air Toxics, and Adverse Health Risks: Environmental Inequities in Tampa Bay, Florida. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2009, 99, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.; Kolpacoff, V.; McCormack, K.; Seewaldt, V.; Hyslop, T. Using Latent Class Modeling to Jointly Characterize Economic Stress and Multipollutant Exposure. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 1940–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, J.; Collins, T.W.; Grineski, S.E. Cancer Risks from Exposure to Vehicular Air Pollution: A Household Level Analysis of Intra-Ethnic Heterogeneity in Miami, Florida. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 112–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.W.; Grineski, S.E.; Chakraborty, J. Household-Level Disparities in Cancer Risks from Vehicular Air Pollution in Miami. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 095008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, J. Cancer Risk from Exposure to Hazardous Air Pollutants: Spatial and Social Inequities in Tampa Bay, Florida. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2012, 22, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Tornero-Velez, R.; Barzyk, T.M. Associations between Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Chemical Concentrations Contributing to Cumulative Exposures in the United States. J. Expo Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, M., Jr.; Sadd, J.L.; Morello-Frosch, R. Who’s Minding the Kids? Pollution, Public Schools, and Environmental Justice in Los Angeles. Soc. Sci. Q. 2002, 83, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.G.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Jesdale, B.M.; Kyle, A.D.; Shamasunder, B.; Jerrett, M. An Index for Assessing Demographic Inequalities in Cumulative Environmental Hazards with Application to Los Angeles, California. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 7626–7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Effect of Exposure to Natural Environment on Health Inequalities: An Observational Population Study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.; Pearce, J.; Mitchell, R.; Day, P.; Kingham, S. The Association between Green Space and Cause-Specific Mortality in Urban New Zealand: An Ecological Analysis of Green Space Utility. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, S.M.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Koo, J.; Yang, J.; Keegan, T.H.; Sangaramoorthy, M.; Hertz, A.; Nelson, D.O.; Cockburn, M.; Satariano, W.A.; et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Impact of Neighborhood Social and Built Environment on Breast Cancer Risk: The Neighborhoods and Breast Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeRouen, M.C.; Schupp, C.W.; Yang, J.; Koo, J.; Hertz, A.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Cockburn, M.; Nelson, D.O.; Ingles, S.A.; Cheng, I.; et al. Impact of Individual and Neighborhood Factors on Socioeconomic Disparities in Localized and Advanced Prostate Cancer Risk. Cancer Causes Control 2018, 29, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, S.L.; Glaser, S.L.; McClure, L.A.; Shema, S.J.; Kealey, M.; Keegan, T.H.; Satariano, W.A. The California Neighborhoods Data System: A New Resource for Examining the Impact of Neighborhood Characteristics on Cancer Incidence and Outcomes in Populations. Cancer Causes Control 2011, 22, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams-White, M.M.; D’Angelo, H.; Perez, L.G.; Dwyer, L.A.; Stinchcomb, D.G.; Oh, A.Y. A National Examination of Neighborhood Socio-Economic Disparities in Built Environment Correlates of Youth Physical Activity. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 22, 101358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoine, T.; Forouhi, N.G.; Griffin, S.J.; Brage, S.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Does Neighborhood Fast-Food Outlet Exposure Amplify Inequalities in Diet and Obesity? A Cross-Sectional Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgoine, T.; Sarkar, C.; Webster, C.J.; Monsivais, P. Examining the Interaction of Fast-Food Outlet Exposure and Income on Diet and Obesity: Evidence from 51,361 UK Biobank Participants. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E.R.; Burgoine, T.; Monsivais, P. Area Deprivation and the Food Environment over Time: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study on Takeaway Outlet Density and Supermarket Presence in Norfolk, UK, 1990–2008. Health Place 2015, 33, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E.R.; Burgoine, T.; Penney, T.L.; Forouhi, N.G.; Monsivais, P. Does Exposure to the Food Environment Differ by Socioeconomic Position? Comparing Area-Based and Person-Centred Metrics in the Fenland Study, UK. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2017, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, S.M.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Yang, J.; Hertz, A.; Cockburn, M.; Shvetsov, Y.B.; Clarke, C.A.; Abright, C.L.; Haiman, C.A.; Le Marchand, L.; et al. Characterizing the Neighborhood Obesogenic Environment in the Multiethnic Cohort: A Multi-Level Infrastructure for Cancer Health Disparities Research. Cancer Causes Control 2018, 29, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Jackson, K.; Egger, S.; Chapman, K.; Rock, V. Shade in Urban Playgrounds in Sydney and Inequities in Availability for Those Living in Lower Socioeconomic Areas. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2014, 38, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, D.T.; Kawachi, I.; Melly, S.J.; Blossom, J.; Sorensen, G.; Williams, D.R. Demographic Disparities in the Tobacco Retail Environment in Boston: A Citywide Spatial Analysis. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, L.; Doscher, C.; Cameron, C.; Robertson, L.; der Deen, F.S.P. How Would the Tobacco Retail Landscape Change If Tobacco Was Only Sold through Liquor Stores, Petrol Stations or Pharmacies? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2020, 44, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker-Seeley, R.D.; Bezold, C.P.; James, P.; Miller, M.; Wallington, S.F. Retail Pharmacy Policy to End the Sale of Tobacco Products: What Is the Impact on Disparity in Neighborhood Density of Tobacco Outlets? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.Y.; Delamater, P.L.; Gottfredson, N.C.; Ribisl, K.M.; Baggett, C.D.; Golden, S.D. Sociodemographic Inequities in Tobacco Retailer Density: Do Neighboring Places Matter? Health Place 2021, 71, 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forastiere, F.; Stafoggia, M.; Tasco, C.; Picciotto, S.; Agabiti, N.; Cesaroni, G.; Perucci, C.A. Socioeconomic Status, Particulate Air Pollution, and Daily Mortality: Differential Exposure or Differential Susceptibility. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2007, 50, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.; Wilson, J.P.; Fehrenbach, J. Parks and Park Funding in Los Angeles: An Equity-Mapping Analysis. Urban Geogr. 2013, 26, 4–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.G.; Logan, T.M.; Zuo, C.T.; Liberman, K.D.; Guikema, S.D. Parks and Safety: A Comparative Study of Green Space Access and Inequity in Five US Cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 201, 103841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Flohr, T.L. Access to Parks for Youth as an Environmental Justice Issue: Access Inequalities and Possible Solutions. Buildings 2014, 4, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcherie, M.; Linn, N.; le Gall, A.R.; Thomas, M.F.; Faure, E.; Rican, S.; Simos, J.; Cantoreggi, N.; Vaillant, Z.; Cambon, L.; et al. Relationship between Urban Green Spaces and Cancer: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Oreja, J.A. Relationships of Area and Noise with the Distribution and Abundance of Songbirds in Urban Greenspaces. Landsc. Urban Plan 2017, 158, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashua-Bar, L.; Hoffman, M.E. Vegetation as a Climatic Component in the Design of an Urban Street: An Empirical Model for Predicting the Cooling Effect of Urban Green Areas with Trees. Energy Build 2000, 31, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward Thompson, C.; Aspinall, P.; Roe, J.; Robertson, L.; Miller, D. Mitigating Stress and Supporting Health in Deprived Urban Communities: The Importance of Green Space and the Social Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretty, J.; Peacock, J.; Sellens, M.; Griffin, M. The Mental and Physical Health Outcomes of Green Exercise. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2005, 15, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Henderson, K.A. Environmental Correlates of Physical Activity: A Review of Evidence about Parks and Recreation. Leis. Sci. 2007, 29, 315–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inequalities in Health in Scotland: What Are They and What Can We Do about Them–Enlighten: Publications. Available online: http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/81903/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J. Mapping the Evolution of “food Deserts” in a Canadian City: Supermarket Accessibility in London, Ontario, 1961–2005. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2008, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, N.; Warm, D.; Margetts, B.; Whelan, A. Assessing the Impact of Improved Retail Access on Diet in a “Food Desert”: A Preliminary Report. Urban Stud. 2016, 39, 2061–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Macintyre, S. “Food Deserts”—Evidence and Assumption in Health Policy Making. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2002, 325, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apparicio, P.; Cloutier, M.S.; Shearmur, R. The Case of Montréal’s Missing Food Deserts: Evaluation of Accessibility to Food Supermarkets. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2007, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, L.; Olsen, J.R.; Shortt, N.K.; Ellaway, A. Do ‘Environmental Bads’ Such as Alcohol, Fast Food, Tobacco, and Gambling Outlets Cluster and Co-Locate in More Deprived Areas in Glasgow City, Scotland? Health Place 2018, 51, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwate, N.O.A.; Yau, C.Y.; Loh, J.M.; Williams, D. Inequality in Obesigenic Environments: Fast Food Density in New York City. Health Place 2009, 15, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charreire, H.; Casey, R.; Salze, P.; Simon, C.; Chaix, B.; Banos, A.; Badariotti, D.; Weber, C.; Oppert, J.M. Measuring the Food Environment Using Geographical Information Systems: A Methodological Review. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, C.E.; Sorensen, G.; Subramanian, S.v.; Kawachi, I. The Local Food Environment and Diet: A Systematic Review. Health Place 2012, 18, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, C.; Moon, G.; Baird, J. Dietary Inequalities: What Is the Evidence for the Effect of the Neighbourhood Food Environment? Health Place 2014, 27, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoine, T.; Forouhi, N.G.; Griffin, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Associations between Exposure to Takeaway Food Outlets, Takeaway Food Consumption, and Body Weight in Cambridgeshire, UK: Population Based, Cross Sectional Study. BMJ 2014, 348, g1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky, J.Y.; Moineddin, R.; Dunn, J.R.; Glazier, R.H.; Booth, G.L. Absolute and Relative Densities of Fast-Food versus Other Restaurants in Relation to Weight Status: Does Restaurant Mix Matter? Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2016, 82, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, L.K.; Appel, L.J.; Franco, M.; Jones-Smith, J.C.; Nur, A.; Anderson, C.A.M. The Relationship of the Local Food Environment with Obesity: A Systematic Review of Methods, Study Quality, and Results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015, 23, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischhacker, S.E.; Evenson, K.R.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Ammerman, A.S. A Systematic Review of Fast Food Access Studies. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e460–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, B.R.; Kim, A.E.; Busey, A.H.; Farrelly, M.C.; Willett, J.G.; Juster, H.R. The Density of Tobacco Retailers and Its Association with Attitudes toward Smoking, Exposure to Point-of-Sale Tobacco Advertising, Cigarette Purchasing, and Smoking among New York Youth. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2012, 55, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leatherdale, S.T.; Strath, J.M. Tobacco Retailer Density Surrounding Schools and Cigarette Access Behaviors among Underage Smoking Students. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 33, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.; Banerjee, A.; Levy, D.; Manzanilla, N.; Cochrane, M. The Spatial Distribution of Underage Tobacco Sales in Los Angeles. Subst. Use Misuse 2009, 43, 1594–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, K.; To, T.; Irving, H.M.; Boak, A.; Hamilton, H.A.; Mann, R.E.; Schwartz, R.; Faulkner, G.E.J. Smoking and Binge-Drinking among Adolescents, Ontario, Canada: Does the School Neighbourhood Matter? Health Place 2017, 47, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitzel, L.R.; Cromley, E.K.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Dela Mater, R.; Mazas, C.A.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Wetter, D.W. The Effect of Tobacco Outlet Density and Proximity on Smoking Cessation. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgoine, T.; Jones, A.P.; Namenek Brouwer, R.J.; Benjamin Neelon, S.E. Associations between BMI and Home, School and Route Environmental Exposures Estimated Using GPS and GIS: Do We See Evidence of Selective Daily Mobility Bias in Children? Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, S.A.; Strombom, I.; Trentham-Dietz, A.; Hampton, J.M.; McElroy, J.A.; Newcomb, P.A.; Remington, P.L. Socioeconomic Risk Factors for Breast Cancer: Distinguishing Individual- and Community-Level Effects. Epidemiology 2004, 15, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, W.F.; Hoffman, K.; Weinberg, J.; Vieira, V.; Aschengrau, A. Community- and Individual-Level Socioeconomic Status and Breast Cancer Risk: Multilevel Modeling on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, S.; Green, S.; Rosenzweig, K.E. Affluence and Breast Cancer. Breast. J. 2016, 22, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Is Breast Cancer a Disease of Affluence, Poverty, or Both? The Case of African American Women. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoi, I.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. The Emergence of the Racial Disparity in U.S. Breast-Cancer Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2349–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, J.; Whitman, S.; Ansell, D. The Black:White Disparity in Breast Cancer Mortality: The Example of Chicago. Cancer Causes Control 2007, 18, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).