The Senior Companion Program Plus (SCP Plus): Examining the Preliminary Effectiveness of a Lay Provider Program to Support African American Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) Caregivers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Examine whether the SCP Plus helped senior companions gain more knowledge of dementia, preparedness of caregiving and sense of competence. We hypothesized that senior companions will improve significantly on these three outcomes.

- Investigate whether the SCP Plus helped African American family caregivers after the intervention when compared to the service as usual (SAU) control group on the major study outcomes. We hypothesized that the SCP Plus will significantly reduce caregiving burden/stress and appraisal of problem behaviors, increase knowledge of ADRD, as well as improve coping skills, level of social support, positive aspects of caregiving, cultural justifications for caregiving, and overall well-being in caregivers.

- Explore the experiences of family caregivers and senior companions with the SCP Plus after intervention.

2. Methods

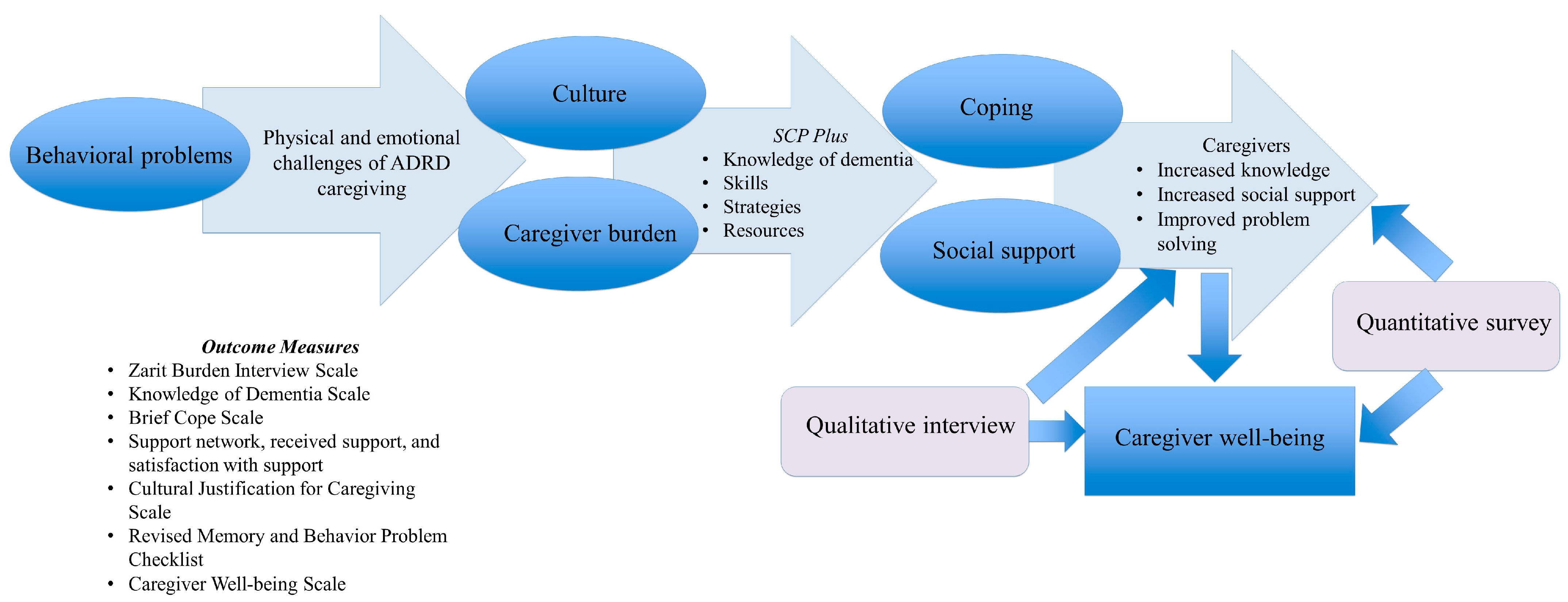

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Intervention

| Modules |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.3. Sample

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Outcomes Measures for Senior Companions

2.4.2. Outcomes Measures for Caregivers

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

“Well…[name of a senior companion] had a good suggestion for me that was perfect. …because Mom would have all these clothes all in her room and she was still pretty much dressing herself and [name of a senior companions] told me to start to kind of remove some of those clothes, but to start putting her outfits together, pants and shirt, you know, and then, you know, put it all together and that’ll make it easier for her [care recipient] to continue to dress herself. And so, yes, I learned that from her. I learned too some little things, especially when she was moving towards her dementia things… I say they like to ‘fiddle with things.’ So I learned some little traits to have her to do to occupy her fingers and that would would settle her down. So I learned some of those things as well.”(Caregiver, Dallas)

“It turned around a lot of things that I was doing that I found out I was doing incorrectly as far as taking care of Mom. For instance. Uh, trying to make her remember things when she couldn’t, and I learned in the I learned in the program that that was not the thing to do. It was more or less to allow her to remember it the way that she remembered it and not try to force her to remember something that she couldn’t. And so. But I yeah, that was just one of the things that stood out with me. So there were several things that that I that it helped me with that I changed in taking care of her that helped out a whole lot. I mean a whole lot it. It was a a lifesaver. The program was a lifesaver.”(Caregiver, Dallas)

“A lot of things cleared up and a lot of things learned. How to handle a person with dementia, Alzheimer’s. You know, sometimes it takes for you to walk through their delusions for them to get to a better place, like even with that.”(Caregiver, Baton Rouge)

“Ohh man ohh it to be honest with you it was very eye opening about a lot of misconceptions about dementia and and honestly not just the misconceptions, but just some things that’s just not known., I mean it, it was so much in that that you learn about. Dementia. Alzheimer’s that you either ever knew. If it wasn’t that you never knew the the myth and the misconception of it”(Caregiver, Baton Rouge)

“I do feel like when we did that [SCP Plus], that it helped us both…I want to say it helped us better bond, to talk, to deal with grandmother…It helped us both to be able to talk to somebody else…that made a difference…It made a difference for her and I to be on the same page at the same time talking about Grandmother.”(Caregiver, Little Rock)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures; Alzheimer’s Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agénor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Feldman, J.M.; Bassett, M.T. How structural racism works—Racist policies as a root cause of US racial health inequities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collins, R.N.; Kishita, N. Prevalence of depression and burden among informal care-givers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 2355–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeken, F.; Rezo, A.; Hinz, M.; Discher, R.; Rapp, M.A. Evaluation of technology-based interventions for informal caregivers of patients with dementia—A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 426–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kaddour, L.; Kishita, N.; Schaller, A. A meta-analysis of low-intensity cognitive behavioral therapy-based interventions for dementia caregivers. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilworth-Anderson, P.; Brummett, B.H.; Goodwin, P.; Williams, S.W.; Williams, R.B.; Siegler, I.C. Effect of race on cultural justifications for caregiving. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2005, 60, S257–S262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A.L.; Roberts, T.J.; King, B.J.; Kennelty, K.A.; Kind, A.J.H. Transitions from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities for persons with dementia: A challenging convergence of patient and system-level needs. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewster, G.S.; Bonds, K.; McLennon, S.; Moss, K.O.; Epps, F.; Lopez, R.P. Missing the mark: The complexity of African American dementia family caregiving. J. Fam. Nurs. 2020, 26, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, G.S.; Epps, F.; Dye, C.E.; Hepburn, K.; Higgins, M.K.; Parker, M.L. The effect of the “Great Village” on psychological outcomes, burden, and mastery in African American caregivers of persons living with dementia. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, L.; Stevens, A.; Guy, D.; Roth, D.L.; Haley, W.E. Impact of two psychosocial interventions on white and African American family caregivers of individuals with dementia. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Drennan, V.; Mackenzie, A.; Greenwood, N. The impact of befriending and peer support on family carers of people living with dementia: A mixed methods study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 76, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corporation for National and Community Service. SCP Operational Handbook. 2020. Available online: https://nationalservice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/SCP%20Complete.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- AmeriCorps. Senior Corps Volunteers Receive Stipend Increase. Available online: https://americorps.gov/newsroom/press-release/2020/senior-corps-volunteers-receive-stipend-increase (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Fields, N.L.; Roark, E.M.; Xu, L. Leveraging volunteers to support dementia family caregivers: An innovative approach to care and support. In Bridging the Family Care Gap; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, E.J.; Georges, A.; Gabbard, S.M.; Pratt, D.J.; Nerino, A.; Roberts, A.S.; Wrightsman, S.M.; Hyde, M. The 2013–2014 Senior Corps study: Foster grandparents and senior companions. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2016, 26, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, C.L.; King, M.D. Lessons learned from implementing a psycho-educational intervention for African American dementia caregivers. Dementia 2010, 9, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, N.L.; Xu, L.; Richardson, V.E.; Parekh, R.; Ivey, D.; Feinhals, G.; Calhoun, M. The Senior Companion Program Plus: A culturally tailored psychoeducational training program (innovative practice). Dementia 2020, 19, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, N.L.; Xu, L.; Richardson, V.E.; Parekh, R.; Ivey, D.; Calhoun, M. Utilizing the Senior Companion Program as a platform for a culturally informed caregiver intervention: Results from a mixed methods pilot study. Dementia 2021, 20, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Badana, A.N.; Burgdorf, J.; Fabius, C.D.; Roth, D.L.; Haley, W.E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of racial and ethnic differences in dementia caregivers’ well-being. Gerontologist 2021, 61, e228–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, M.P.; Knight, B.G. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, B.G.; Sayegh, P. Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2010, 65, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.S.; Connell, C.M. Illness representations among first-degree relatives of people with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2000, 14, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.L.; Jimenez, D.E.; Cucciare, M.A.; Tong, H.-Q.; Gallagher-Thompson, D. Ethnic differences in beliefs regarding Alzheimer disease among dementia family caregivers. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, W.S.O.; De Haan, R.J.; Pijnenborg, J.M.A.; Limburg, M.; Van den Bos, G.A.M. Assessment of burden in partners of stroke patients with the sense of competence questionnaire. Stroke 1998, 29, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, A.P.; van Hout, H.P.; van Marwijk, H.W.; Nijpels, G.; Gundy, C.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.J.; de Vet, H.C.; Schellevis, F.G.; Stalman, W.A. Sense of competence questionnaire among informal caregivers of older adults with dementia symptoms: A psychometric evaluation. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2007, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M.J.; Persoon, J.M.; Felling, A.J. Predictors of sense of competence in caregivers of demented persons. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 43, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archbold, P.G.; Stewart, B.J.; Greenlick, M.R.; Harvath, T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res. Nurs. Health 1990, 13, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.L.; Hayman-White, K. Measuring the psychosocial characteristics of family caregivers of palliative care patients: Psychometric properties of nine self-report instruments. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2006, 31, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucciarelli, G.; Savini, S.; Byun, E.; Simeone, S.; Barbaranelli, C.; Vela, R.J.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Psychometric properties of the Caregiver Preparedness Scale in caregivers of stroke survivors. Heart Lung 2014, 43, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontol. 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachner, Y.G.; O’rourke, N. Reliability generalization of responses by care providers to the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging Ment. Health 2007, 11, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, G.J. Religious coping, positive aspects of caregiving, and social support among Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. Clin. Gerontol. 2014, 37, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn Longmire, C.V.; Knight, B.G. Confirmatory factor analysis of a brief version of the Zarit Burden Interview in Black and White dementia caregivers. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Katona, C.; Livingston, G. Validity and reliability of the brief COPE in carers of people with dementia: The LASER-AD Study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2008, 196, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M.; Sandler, I.N.; Ramsay, T.B. Preliminary development of a scale of social support: Studies on college students. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1981, 9, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N. Negative interaction and satisfaction with social support among older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 1995, 50, P59–P73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N.; Markides, K. Measuring social support among older adults. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1990, 30, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubben, J.E. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam. Community Health 1988, 11, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle, S.H.; Burgio, L.; Burns, R.; Coon, D.; Czaja, S.J.; Gallagher-Thompson, D.; Gitlin, L.N.; Klinger, J.; Koepke, K.M.; Lee, C.C.; et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.; Czaja, S.J.; Schulz, R. The moderating influence of demographic characteristics, social support, and religious coping on the effectiveness of a multicomponent psychosocial caregiver intervention in three racial ethnic groups. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2010, 65, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teri, L.; Truax, P.; Logsdon, R.; Uomoto, J.; Zarit, S.; Vitaliano, P.P. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychol. Aging 1992, 7, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Durkin, D.W.; Hilgeman, M.M.; Harris, G.; Gaugler, J.E.; Wardian, J.; Allen, R.S.; Burgio, L.D. Predicting desire for institutional placement among racially diverse dementia family caregivers: The role of quality of care. Gerontol. 2013, 53, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.L.; Burgio, L.D.; Gitlin, L.N.; Gallagher-Thompson, D.; Coon, D.W.; Belle, S.H.; Stevens, A.B.; Burns, R. Psychometric analysis of the Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist: Factor structure of occurrence and reaction ratings. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgeman, M.M.; Allen, R.S.; DeCoster, J.; Burgio, L.D. Positive aspects of caregiving as a moderator of treatment outcome over 12 months. Psychol. Aging 2007, 22, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarlow, B.J.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Belle, S.H.; Rubert, M.; Ory, M.G.; Gallagher-Thompson, D. Positive aspects of caregiving: Contributions of the REACH project to the development of new measures for Alzheimer’s caregiving. Res. Aging 2004, 26, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilworth-Anderson, P.; Goodwin, P.Y.; Williams, S.W. Can culture help explain the physical health effects of caregiving over time among African American caregivers? J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2004, 59, S138–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebb, S. An aid to empowerment: A caregiver well-being scale. Health Soc. Work 1995, 20, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebb, S.S.; Berg-Weger, M.; Rubio, D.M. The Caregiver Well-Being Scale: Developing a short-form rapid assessment instrument. Health Soc. Work 2013, 38, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosebush, C.E.; Stabler, H.; Nkimbeng, M.; Louwagie, K.; Fields, N.L.; Jutkowitz, E.; Shippee, T.P.; Gaugler, J.E. The Porchlight Project: A Pilot Study to Adapt the Senior Companion Program to Enhance Memory Care Services and Supports. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211017651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, D.R.; Brady, E.; Wilkerson, D.; Yi, E.-H.; Karanam, Y.; Callahan, C.M. Comparing crowdsourcing and friendsourcing: A social media-based feasibility study to support Alzheimer disease caregivers. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 6, e6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, E.; Semple, A.C.; de Waal, H. Quantifying the benefits of peer support for people with dementia: A Social Return on Investment (SROI) study. Dementia 2018, 17, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, L.K.L.; Min, S.H.; Dennis, C.-A.; Østbye, T.; Johnson, K.S.; Xu, H. Interventions to promote dementia knowledge among racial/ethnic minority groups: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, V.E.; Fields, N.; Won, S.; Bradley, E.; Gibson, A.; Rivera, G.; Holmes, S.D. At the intersection of culture: Ethnically diverse dementia caregivers’ service use. Dementia 2019, 18, 1790–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.C.; Rocco, T.S. Disparities in healthcare for racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2014, 2014, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, L.K.; Welter, E.; Leverenz, J.; Lerner, A.J.; Udelson, N.; Kanetsky, C.; Sajatovic, M. A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: Can we move the stigma dial? Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teahan, A.; Lafferty, A.; McAuliffe, E.; Phelan, A.; O’Sullivan, L.; O’Shea, D.; Nicholson, E.; Fealy, G. Psychosocial interventions for family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Aging Health 2020, 32, 1198–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Ji, M.; Leng, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Comparative efficacy of 11 non-pharmacological interventions on depression, anxiety, quality of life, and caregiver burden for informal caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 129, 104204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, S.E.; Clarke, C.L.; Wilkinson, H.; Alexjuk, E.J.; Wilcockson, J.; Robinson, L.; Reynolds, J.; McClelland, S.; Corner, L.; Cattan, M. “We’re all thrown in the same boat…”: A qualitative analysis of peer support in dementia care. Dementia 2016, 15, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epps, F.; Rose, K.M.; Lopez, R.P. Who’s your family?: African American caregivers of older adults with dementia. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2019, 12, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desin, P.J.; Caban-Holt, A.M.; Abner, E.L.; Van Eldik, L.J.; Schmitt, F.A. Factors associated with unmet needs among African-American dementia care providers. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2016, 5, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Samus, Q.M.; Gaugler, J.E.; Rebok, G.W. Going for the win-win-win: Harnessing the power of senior volunteerism to address dementia care and promote health. Innov. Aging 2019, 3 (Suppl. S1), S794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-T.; Mak, E.P.M.; Kwok, T.; Fung, H.; Lam, L.C.W. Benefit-finding intervention delivered individually to Alzheimer family caregivers: Longer-term outcomes of a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 75, 1884–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzarano, F.; Moxley, J.; Pillemer, K.; Czaja, S.J. Family matters: Cross-cultural differences in familism and caregiving outcomes. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitlin, L.N.; Marx, K.; Stanley, I.H.; Hodgson, N. Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: State-of-the-science and next steps. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Key Measurements | Pre-Test | Post-Test | Mean Differences (95% CI) | Statistical Test, p-Values * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium (Range) | Medium (Range) | |||

| Knowledge of AD/Dementia (Control) | 8.00 (6–10) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Knowledge of AD/Dementia (SCP Plus) | 10.00 (5–11) | 12.00 (10–14) | 2.82 (1.45–4.19) | z = −2.97, p = 0.003 ** |

| Sense of Competence (Control) | 46.0 (29–53) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sense of Competence (SCP Plus) | 46.00 (36–55) | 45.00 (37–55) | 0.64 (−0.90–2.18) | z = −0.67, p = 0.501 |

| Preparedness for Caregiving (Control) | 28.00 (23–32) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Preparedness for Caregiving (SCP Plus) | 24.0 (21–39) | 31.00 (23–40) | 3.82 (1.72–5.92) | z = −2.81, p = 0.005 ** |

| Key Measurements | Pre-Test (n = 11) | Post-Test (n =9) | Follow-Up Test (n =7) | Statistical Test a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Range) | Median (Range) | Median (Range) | ||

| ADLs of CR | 2.5 (0–6) | 3.0 (0–6) | 6.0 (1–6) | χ2(2) = 3.12, p = 0.21 |

| IADLs of CR | 8.0 (6–8) | 8.0 (7–8) | 8.0 (7–8) | χ2(2) = 2.00, p = 0.37 |

| Knowledge of AD/Dementia (KAD) | 9.0 (7–13) | 12.0 (8–14) | 11.0 (10–14) | χ2(2) = 8.72, p = 0.01 3,* |

| Caregiving burden (Zarit burden) | 39.0 (8–63) | 22.0 (10–45) | 13.5 (4–30) | F(2,10) = 20.47, p < 0.001 1,3,*** |

| Social support | ||||

| Social support network | 14.0 (3–30) | 19.0 (10–28) | 21.0 (17–27) | χ2(2) = 0.96, p = 0.62 |

| Received social support | 5.0 (3–7) | 5.0 (4–7) | 4.0 (3–4) | χ2(2) =3.90, p = 0.14 |

| Satisfaction with social support (SSS) | 6.0 (0–12) | 12.0 (3–12) | 12.0 (5–12) | χ2(2) = 6.33, p = 0.04 1,3,* |

| Negative interactions | 3.0 (0–11) | 1.0 (0–6) | 0.0 (0–6) | χ2(2) = 3.36, p = 0.19 |

| Coping skills | 75.0 (55–98) | 85.0 (74–101) | 85.0 (61–101) | F(2,12) = 4.10, p = 0.04 1,3,* |

| RMBPC | 10.0 (7–13) | 10.0 (1–18) | 11.5 (3–17) | F(2,10) = 0.28, p = 0.76 |

| RMBPC_bother | 8.0 (0–36) | 10.0 (0–32) | 4.5 (0–40) | F(2,10) = 0.12, p = 0.89 |

| Positive aspect of caregiving (PAC) | 36.0 (23–49) | 49.0 (30–55) | 52.0 (36–55) | χ2(2) = 10.16, p = 0.006 1,3,** |

| Cultural justifications for caregiving (CJC) | 31.0 (21–37) | 36.0 (13–40) | 39.0 (26–40) | χ2(2) = 4.88, p = 0.09 £ |

| Well-being of caregiver (WBC) | 63.0 (31–76) | 67.0 (42–80) | 70.0 (43–76) | χ2(2) = 4.75, p = 0.09 £ |

| Key Measurements | Pre-Test | Post-Test | Follow Up-Test | Statistical Test a,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Median | Median | ||

| KAD (Control) | 9.0 | 10.5 | 12.0 | χ2(2) = 3.20, p = 0.20 |

| KAD (SCP Plus) | 9.5 | 12.0 | 11.0 | χ2(2) = 6.53, p = 0.04 1,* |

| ZBI (Control) | 18.0 | 18.5 | 7.0 | F(2,2) = 2.94, p = 0.25 |

| ZBI (SCP Plus) | 40.0 | 32.0 | 15.0 | F(2,6) = 17.65, p = 0.003 3,** |

| Coping (Control) | 73.0 | 82.0 | 90.0 | F(2,4) = 0.42, p = 0.68 |

| Coping (SCP Plus) | 81.0 | 96.0 | 79.0 | F(2,6) = 4.44, p = 0.07 £ |

| SSS (Control) | 9.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | χ2(2) = 0.67, p = 0.72 |

| SSS (SCP Plus) | 3.5 | 4.0 | 11.5 | χ2(2) = 6.53, p = 0.04 1,3,* |

| PAC (Control) | 42.0 | 49.0 | 52.0 | χ2(2) = 3.8, p = 0.15 |

| PAC (SCP Plus) | 33.5 | 49.0 | 52.5 | χ2(2) = 6.53, p = 0.04 1,3,* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Fields, N.L.; Williams, I.C.; Gaugler, J.E.; Kunz-Lomelin, A.; Cipher, D.J.; Feinhals, G. The Senior Companion Program Plus (SCP Plus): Examining the Preliminary Effectiveness of a Lay Provider Program to Support African American Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075380

Xu L, Fields NL, Williams IC, Gaugler JE, Kunz-Lomelin A, Cipher DJ, Feinhals G. The Senior Companion Program Plus (SCP Plus): Examining the Preliminary Effectiveness of a Lay Provider Program to Support African American Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) Caregivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(7):5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075380

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ling, Noelle L. Fields, Ishan C. Williams, Joseph E. Gaugler, Alan Kunz-Lomelin, Daisha J. Cipher, and Gretchen Feinhals. 2023. "The Senior Companion Program Plus (SCP Plus): Examining the Preliminary Effectiveness of a Lay Provider Program to Support African American Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) Caregivers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 7: 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075380

APA StyleXu, L., Fields, N. L., Williams, I. C., Gaugler, J. E., Kunz-Lomelin, A., Cipher, D. J., & Feinhals, G. (2023). The Senior Companion Program Plus (SCP Plus): Examining the Preliminary Effectiveness of a Lay Provider Program to Support African American Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) Caregivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075380