Smartphone Apps for Domestic Violence Prevention: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

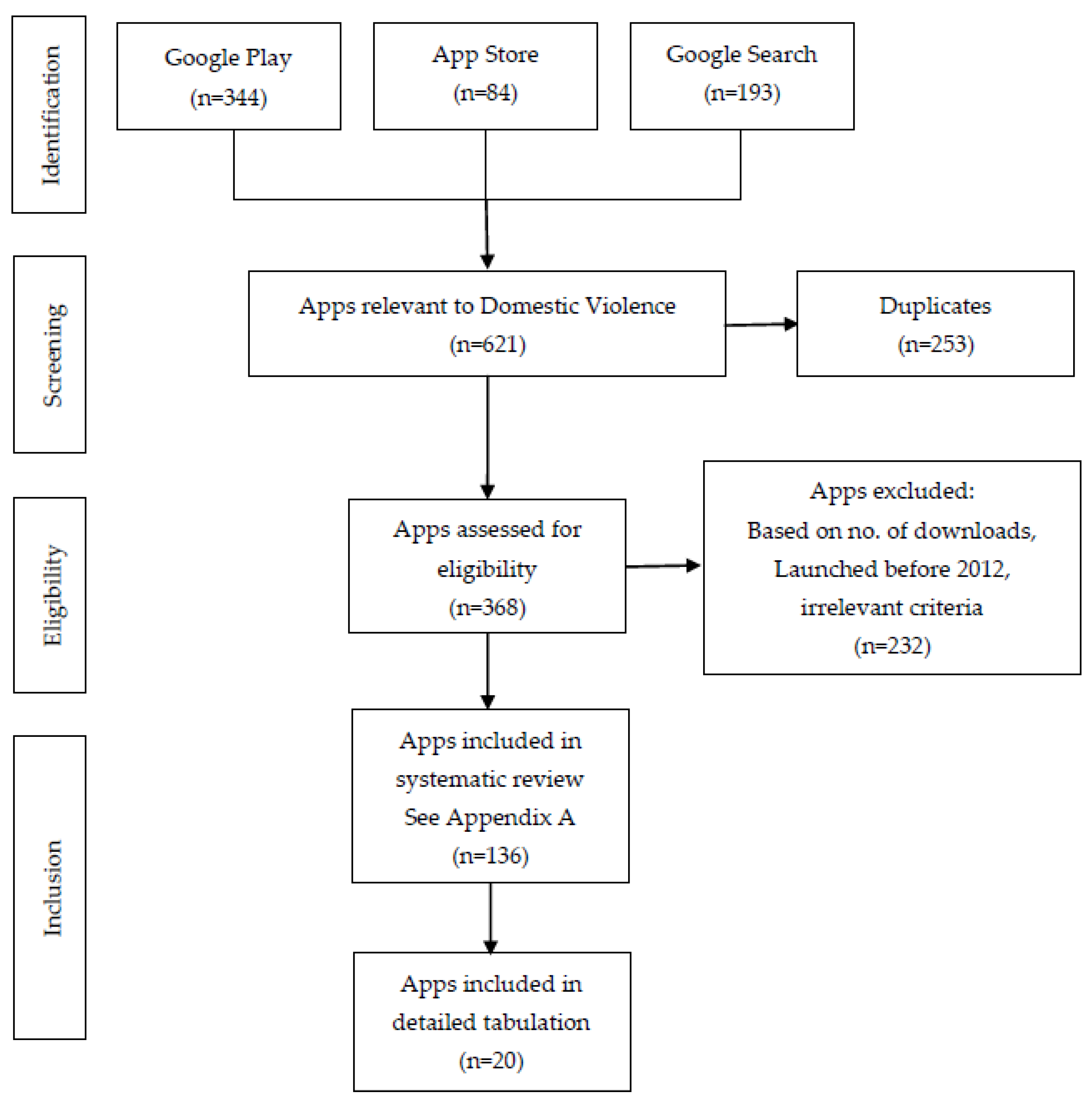

2.1. Search

2.2. Screening

2.3. Eligibility

- Apps released or updated after 2011 and till September 2022.

- The number of downloads of the apps > 100.

- The language of the apps English, Spanish, Urdu, or multilingual (English and local languages of the region).

- Applications were chosen from certain geographical regions based on the limitations placed by the download availability of apps, the lack of apps available with distinctive features and duplication of apps.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Classification of the Apps

- Emergency assistance apps was the first category that included the majority of the apps. These apps were created to keep individual users safe. Most of them worked in such a way that they asked for emergency contact numbers during registration, and the app can call these numbers in an emergency. Users can trigger Save Our Souls (SOS) alerts. Some apps allowed users to seek assistance by sharing their current location and sending an alert message to pre-selected numbers.

- Avoidance apps fell into the second category that provides victims with a strategy for avoiding domestic violence situations, as well as emergency assistance.

- Informative apps fell into the third category that educated users on how to recognize and respond to violent situations.

- Legal information apps was the fourth category that includes all the apps that provide legal information or terms related to the law. These apps assist users in understanding legal terms by providing books of law and violent acts. Victims can also contact police, law enforcement agencies, firefighters, and hospitals by pressing a designated button on these apps.

- Self-assessment apps was the final category, and these apps assist users in understanding the term violence and determining the possibility of danger or abuse in their relationship. Through these apps, users may be able to connect with services such as lawyers, shelter homes, social workers, NGOs, and hospitals.

3.2. Trends with Regard to Apps Distribution

3.3. Critical Analysis

3.4. Limitations

3.5. Open-Ended Challenges

- Apps should be supported in all smartphone platforms (iOS, Android, etc.).

- Internet connectivity issues: alternative mechanism required.

- Literacy issue: the majority of the apps are in the English language.

- Storage issue: if we store the data in a mobile phone’s memory.

- Privacy is one of the major concerns of domestic violence app users.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Year of Last Update | App Name | No. of Downloads | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidance | ||||

| 1 | 2021 | bSafe | 1,000,000 | Northeast America |

| 2 | 2020 | Guardly * | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 3 | 2022 | Life360 Family Locator App * | 50,000,000 | Northeast America |

| 4 | 2021 | StaySafe * | 10,000 | Europe |

| 5 | 2022 | LiveSafe * | 100,000 | Northeast America |

| 6 | 2013 | React Mobile * | 5000 | Northeast America |

| 7 | 2017 | Emergency Chat | 5000 | Europe |

| 8 | 2016 | The Safety Plan Navigator | 500 | Oceania |

| 9 | 2017 | Circle of 6 * | 100,000 | Northeast America |

| 10 | 2017 | My Safety Companion | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 11 | 2017 | PTSD Hub | 5000 | Europe |

| 12 | 2017 | Safety First | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 13 | 2018 | Domestic Violence Prevention | 5000 | Northeast America |

| 14 | 2018 | Tech Safety | 5000 | Northeast America |

| 15 | 2020 | Be Safe | 1000 | South Asia |

| 16 | 2019 | Family Welfare | 500 | Africa |

| 17 | 2019 | My Angel Guard * | 100 | Northeast America |

| 18 | 2021 | DocuSAFE Evidence Collection | 500 | Europe |

| 19 | 2021 | HELP App-Prevention Resources | 100 | Northeast America |

| 20 | 2021 | PSCA-Public Safety | 50,000 | South Asia |

| 21 | 2020 | Punjab Police Khidmat (Service) App | 100,000 | South Asia |

| 22 | 2020 | Purse Power | 100 | Northeast America |

| 23 | 2022 | DoD Safe Helpline | 500 | Northeast America |

| 24 | 2022 | FamilyTime Parental Controls and Screen Time App | 1,000,000 | East Asia |

| 25 | 2021 | GBV Pocket Guide | 5000 | Europe |

| 26 | 2021 | Helpseeker | 5000 | Northeast America |

| 27 | 2022 | MMGuardian Parental Control App for Child Phone | 500,000 | Northeast America |

| 28 | 2022 | Senior Safety App, GPS Tracker, Fall Alerts and More | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 29 | 2021 | Therapeer: Peer Emotional Support | 50,000 | Northeast America |

| Informative | ||||

| 30 | 2021 | SafeNight * | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 31 | 2015 | Domestic Violence Inventory | 50,000 | Northeast America |

| 32 | 2017 | Aspire News * | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 33 | 2017 | Know My Rights | 10,000 | Africa |

| 34 | 2017 | Know My Rights | 10,000 | Africa |

| 35 | 2018 | Domestic Violence Prevention | 5000 | Northeast America |

| 36 | 2018 | How to Move on | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 37 | 2021 | NFAAS | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 38 | 2018 | Rape Crisis Counseling | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 39 | 2019 | 10 Signs Your Husband Is Emotionally Abusive | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 40 | 2020 | Becoming A Better Woman-Stronger Women | 10,000 | Europe |

| 41 | 2021 | Psychopedia | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 42 | 2022 | Safe Place | 150 | Northeast America |

| 43 | 2020 | Shelter Safe * | 100,000 | Northeast America |

| 44 | 2020 | The Health and Safety App | 5000 | Europe |

| 45 | 2020 | The Slipout | 100 | Northeast America |

| 46 | 2020 | Womaze: Self-Care and Motivation | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 47 | 2022 | Best free and safe social app for women-SHEROES | 1,000,000 | South Asia |

| 48 | 2021 | Facing Violence/Rory Miller | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 49 | 2022 | Google Family Link for parents | 50,000,000 | Northeast America |

| 50 | 2021 | Homeless Resources-Shelter App | 100,000 | Northeast America |

| 51 | 2022 | My Safetipin: Complete Safety App | 50,000 | South Asia |

| 52 | 2021 | Relationship Advice for women | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 53 | 2021 | Self Help | 10,000 | Europe |

| 54 | 2022 | Teen Counseling | 50,000 | Northeast America |

| 55 | 2022 | WanderSafe Safety App | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 56 | 2021 | Domestic Violence Act (Hindi) | 10000 | South Asia |

| 57 | 2022 | DOMINO -stop domestic violence | 100 | Europe |

| 58 | 2021 | Women’s Human Rights | 10000 | Europe |

| Emergency Assistance | ||||

| 59 | 2013 | Eyewatch * | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 60 | 2015 | Easy Rescue * | 100,000 | Europe + Asia |

| 61 | 2015 | Emergencies (CH) | 5000 | Europe |

| 62 | 2020 | Emergency Call App | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 63 | 2021 | AlertNow! | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 64 | 2016 | APS Panic Button | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 65 | 2019 | Quick SOS Help-Emergency Contact Call with Siren Alert Alarm | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 66 | 2016 | Rescue Me-I Need Help | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 67 | 2016 | SOS Button-Family Locator for Safety and Care | 10,000 | Europe |

| 68 | 2016 | SOS-need help | 500 | South Asia |

| 69 | 2017 | SEND HELP-SOS Panic Button | 5000 | Northeast America |

| 70 | 2017 | SOS Watch | 100 | Northeast America |

| 71 | 2021 | AlertCops * | 500,000 | Europe |

| 72 | 2018 | NCDV | 5000 | Europe |

| 73 | 2021 | GetHomeSafe-Personal Safety | 10,000 | Oceania |

| 74 | 2019 | iProtect | 100 | Africa |

| 75 | 2021 | Mayday Safety | 5000 | Northeast America |

| 76 | 2019 | ProtectMii-Personal Safety App with Panic Alarm | 5000 | Europe |

| 77 | 2020 | B.E.S.T Emergency App | 100 | Africa |

| 78 | 2020 | Carelife-Personal Safety App | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 79 | 2020 | DV ASSIST | 1000 | Europe |

| 80 | 2021 | Emergency SOS Safety Alert Message | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 81 | 2020 | HelpCall-Emergency call | 5000 | Europe |

| 82 | 2022 | Helpline 1099-Ministry of Human Rights * | 1000 | South Asia |

| 83 | 2020 | ICE: Personal Safety App | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 84 | 2020 | NineOneOne-Emergency Dialer | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 85 | 2021 | UrSafe: Safety and Security App | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 86 | 2022 | Punjab Police-Women Safety App * | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 87 | 2020 | RAKSHA-Women Safety App | 1000 | South Asia |

| 88 | 2021 | Safety App for Silent Beacon | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 89 | 2020 | Save | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 90 | 2020 | Shake2Safety-Personal Safety | 100,000 | South Asia |

| 91 | 2022 | SOS Lifesaver-the best life saving Emergency app | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 92 | 2022 | WeHelp!-Personal Security | 100,000 | Northeast America |

| 93 | 2020 | Woman Safety Resq | 100 | South Asia |

| 94 | 2022 | App-Elles: against gender-based violence | 10,000 | Europe |

| 95 | 2022 | Baxta-Personal Safety and Family Locator and Tracker | 10,000 | Oceania |

| 96 | 2021 | bSafe * | 1,000,000 | Northeast America |

| 97 | 2021 | bSafe-Never Walk Alone | 1,000,000 | Europe |

| 98 | 2022 | Call For Help-Emergency SOS | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 99 | 2021 | Emergency Contact List | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 100 | 2021 | Emergency SOS Safety Alert-Personal Alarm App | 100,000 | Oceania |

| 101 | 2021 | Guardians-Personal and Family Safety | 100,000 | South Asia |

| 102 | 2021 | Humqadam-GBV Response Services | 100 | South Asia |

| 103 | 2022 | Microsoft Family Safety | 500,000 | Northeast America |

| 104 | 2021 | My SOS Family Emergency Alert | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 105 | 2022 | Parental Control App and Location Tracker-FamiSafe | 1,000,000 | East Asia |

| 106 | 2022 | Rosenbauer EMEREC | 500 | Northeast America |

| 107 | 2021 | Safe NYU | 5000 | Northeast America |

| 108 | 2021 | Safe Walk | 1000 | South Asia |

| 109 | 2022 | Safety-Help-SOS | 50,000 | Europe + Asia |

| 110 | 2021 | SafeUP-Women’s Safety Net | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 111 | 2022 | SHESafe | 5000 | South Asia |

| 112 | 2021 | SHESafe | 5000 | South Asia |

| 113 | 2022 | Sister-Personal safety app | 10,000 | Europe |

| 114 | 2021 | Tiger Force Awaz Pakistan-Public Safety App | 5000 | South Asia |

| 115 | 2022 | WeeCare Health|Emergency Android App|Be Safe | 10,000 | Africa |

| 116 | 2021 | WEPROTECT | 100 | Europe |

| 117 | 2021 | Women Protection Cell | 100 | South Asia |

| 118 | 2021 | Women Safety | 100,000 | South Asia |

| 119 | 2022 | Women Safety with Security Protection | 1000 | South Asia |

| Legal information | ||||

| 120 | 2016 | Domestic Violence Act, 2005 | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 121 | 2016 | Indian Family Laws | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 122 | 2022 | Domestic Violence Law | 500 | South Asia |

| 123 | 2018 | Domestic Violence in India Protection Law | 500 | South Asia |

| 124 | 2018 | Family Laws in India | 10,000 | South Asia |

| 125 | 2019 | VictimsVoice * | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 126 | 2020 | LawRights | 10,000 | Africa |

| 127 | 2021 | Family Law Books Offline | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 128 | 2022 | Law App | 100,000 | South Asia |

| 129 | 2022 | Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act2005 | 10,000 | South Asia |

| Self-Assessment | ||||

| 130 | 2022 | myPlan * | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 131 | 2019 | RUSafe * | 1000 | Northeast America |

| 132 | 2021 | Bright Sky* | 10,000 | Europe |

| 133 | 2018 | Victory for Victims | 100 | Northeast America |

| 134 | 2020 | NarcStop-Narcissistic abuse and recovery guide | 1000 | Europe |

| 135 | 2022 | United We Care-Online Counselling and Therapy | 10,000 | Northeast America |

| 136 | 2021 | JAZBA GBV Application | 100 | South Asia |

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health: Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Violence against Women; FRH/WHD/96.26; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Galvez, R.M.; Martin-Pelaez, S.; Martinez-Galiano, J.M.; Khan, K.S.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A. Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence in Pregnancy: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 707. [Google Scholar]

- Cumiskey, K.M.; Brewster, K. Mobile Phones or Pepper Spray? Fem. Media Stud. 2012, 12, 590–599. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Smartphone Subscriptions Worldwide 2016–2027. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Worldometer World Population Milestones. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Bankmycell How Many Mobile Connections Are There Worldwide? Available online: https://www.bankmycell.com/blog/how-many-phones-are-in-the-world (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- The Free Dictionary Mobile Connection. Available online: https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/mobile+connection (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Statista Number of Apps Available in Leading App Stores as of 1st Quarter 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Kwon, H.S.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.H.; Song, B.R.; Oh, J.A.; Han, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Cha, B.Y.; Lee, K.; et al. Development of web-based diabetic patient management system using short message service (SMS). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2004, 66 (Suppl. 1), S133–S137. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, J.; McPherson, A.; Hamilton, J.; Birken, C.; Coons, M.; Iyer, S.; Agarwal, A.; Lalloo, C.; Stinson, J. Mobile Apps for Weight Management: A Scoping Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016, 4, e87. [Google Scholar]

- Obermayer, J.L.; Riley, W.T.; Asif, O.; Jean-Mary, J. College smoking-cessation using cell phone text messaging. J. Am. Coll. Health 2004, 53, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, A.; Corbett, T.; Bramley, D.; Riddell, T.; Wills, M.; Lin, R.B.; Jones, M. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tob. Control. 2005, 14, 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Vidrine, D.J.; Arduino, R.C.; Lazev, A.B.; Gritz, E.R. A randomized trial of a proactive cellular telephone intervention for smokers living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS 2006, 20, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre, R.T.P.; McCoy, M.K.; Roan, M. Development guidelines from a study of suicide prevention mobile applications (Apps). J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2013, 31, 269–293. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, A.L.; Makin, J.D.; Kydd, A.S.; Biriotti, M.; Forsyth, B.W. A pilot study using interactive SMS support groups to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in South Africa. J. Telemed. Telecare 2012, 18, 399–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, K.; Dillingham, R.; Reynolds, G.; Hettema, J.; Freeman, J.; Hosseinbor, S.; Winstead-Derlega, C. Development of a personalized bidirectional text messaging tool for HIV adherence assessment and intervention among substance abusers. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2014, 46, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw, L.; Thabane, L.; Ongolo-Zogo, P.; Lester, R.T.; Mills, E.J.; Smieja, M.; Dolovich, L.; Kouanfack, C. The Cameroon Mobile Phone SMS (CAMPS) trial: A randomized trial of text messaging versus usual care for adherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46909. [Google Scholar]

- Puccio, J.A.; Belzer, M.; Olson, J.; Martinez, M.; Salata, C.; Tucker, D.; Tanaka, D. The use of cell phone reminder calls for assisting HIV-infected adolescents and young adults to adhere to highly active antiretroviral therapy: A pilot study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2006, 20, 438–444. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, R.; Shet, A.; Antony, J.; Sidney, K.; Arumugam, K.; Krishnamurthy, S.; D‘Souza, G.; DeCosta, A. Supporting adherence to antiretroviral therapy with mobile phone reminders: Results from a cohort in South India. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40723. [Google Scholar]

- Brignone, L.; Edleson, J.L. The dating and domestic violence app rubric: Synthesizing clinical best practices and digital health app standards for relationship violence prevention smartphone apps. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 1859–1869. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel, E.; Donelle, L.; Hall, J.; Rodger, S. Intimate partner violence: A review of online interventions. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2018, 44, 204–219. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhut, K.; Sauerborn, E.; García-Moreno, C.; Wild, V. Mobile applications addressing violence against women: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e001954. [Google Scholar]

- Moret, J.D.; Todd, A.; Rose, L.; Pollitt, E.; Anderson, J. Phone Apps for Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Prevention and Response: Systematic Search on App Stores. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e28959. [Google Scholar]

- O’Campo, P.; Velonis, A.; Buhariwala, P.; Kamalanathan, J.; Hassan, M.A.; Metheny, N. Design and development of a suite of intimate partner violence screening and safety planning web apps: User-centered approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24114. [Google Scholar]

- Westmarland, N.; Hardey, M.; Bows, H.; Branley, D.; Chowdhury, M.; Wheatley, K.; Wistow, R. Protecting women’s safety? The use of smartphone ‘apps’ in relation to domestic and sexual violence. Soc. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2013, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, B.S.; Schwartz, T.A.; Pawlik, T.M. MOOSE Reporting Guidelines for Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, 787–788. [Google Scholar]

- Libraries, U. Gender, Domestic Violence, and Social Justice (GSWS 3000): Choosing Keywords. Available online: https://guides.temple.edu/domesticviolence (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Punjab Police—Women Safety App, Punjab Safe Cities Authority. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.psca.ppic3.womensafety&hl=en (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- AlertCops. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.alertcops4.app&hl=en (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- HelpLine 1099. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.sos.sossystem&hl=en (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Eyewatch SOS for Women. Available online: https://apkcombo.com/eyewatch-sos-for-women/com.eyewatchw/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Easy Rescue. Available online: https://www.vodafone.com/vodafone-foundation/focus-areas/apps-against-abuse (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- LiveSafe. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.livesafe.activities&hl=en (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Life360: Family Locator & GPS Tracker for Safety. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.life360.android.safetymapd&hl=en (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Circle of 6. Available online: https://www.circleof6app.com/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- bSafe—Never Walk Alone. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.bipper.app.bsafe&hl=en (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Guardly. Available online: https://appsagainstabuse.devpost.com/submissions/4899-guardly (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Stay Safe. Available online: https://staysafeapp.com/en-us/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- My Angel Guard. Available online: https://m.apkpure.com/my-angel-guard/com.secugo.myangelguard (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- React Mobile. Available online: https://www.reactmobile.com/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Aspire News App. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.aspireapp&hl=en_US (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Shelter Safe. Available online: https://sheltersafe.ca/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- SafeNight. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.caravan.safenight (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- VictimsVoice. Available online: https://victimsvoice.app/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- RUSafe. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.newton.WomenShelter&hl=en&gl=US (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- My Plan. Available online: https://www.myplanapp.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Arnhold, M.; Quade, M.; Kirch, W. Mobile Applications for Diabetics: A Systematic Review and Expert-Based Usability Evaluation Considering the Special Requirements of Diabetes Patients Age 50 Years or Older. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e104. [Google Scholar]

- Hamine, S.; Gerth-Guyette, E.; Faulx, D.; Green, B.B.; Ginsburg, A.S. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e52. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Lum, E.; Jimenez, G.; Semwal, M.; Sloot, P.; Car, J. Medication management support in diabetes: A systematic assessment of diabetes self-management apps. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh, J.W.L.; Cox, A.; Anderson, S.; Liew, B.; Olsen, A.; Schram, B.; Furness, J. Reliability and validity of clinically accessible smartphone applications to measure joint range of motion: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215806. [Google Scholar]

- Knitza, J.; Tascilar, K.; Messner, E.M.; Meyer, M.; Vossen, D.; Pulla, A.; Bosch, P.; Kittler, J.; Kleyer, A.; Sewerin, P.; et al. German Mobile Apps in Rheumatology: Review and Analysis Using the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e14991. [Google Scholar]

- Marcolino, M.S.; Oliveira, J.A.Q.; D’Agostino, M.; Ribeiro, A.L.; Alkmim, M.B.M.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. The Impact of mHealth Interventions: Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e23. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, J.M.; Prichard, I.; Kemps, E. A Comparison of Physical Activity Mobile Apps with and Without Existing Web-Based Social Networking Platforms: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12687. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, M.A. Is Domestic Violence Endemic in Pakistan: Perspective from Pakistani Wives. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2003, 19, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mhealth: New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Respect Women: Preventing Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/violence/respect-women-framework/en/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Heise, L. What Works to Prevent Partner Violence? An Evidence Overview; STRIVE Research Consortium, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cloud Speech-to-Text. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/speech-to-text (accessed on 1 November 2022).

| Category | Features | Distinctiveness | Critical Review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency Assistance |

| App provides location review option through which a person can view the reviews against location safety before visiting that place [29]. The app has an option for deaf people to use this app and it can send a warning if the area have any security issues [30]. Complaint system against domestic violence [31]. Accelerometer based trigger is available that automatically set an alert in case the phone detect a fall [32]. App generates an alert by shaking their phones [33]. |

|

| Avoidance |

| The apps have option to report a suspicious activity by sharing pictures, audio and video of that location [34]. The app provides geo fences facility [35]. Ref. [36] has access to local hotlines such as, suicide prevention, HIV info, national domestic violence etc. Optional siren and flashlight option available [37]. App offers a support system for traumas and anxiety related responses for reassurance [38]. The battery is low or runs out of power, the app work to tackle the violent situation [39]. User’s medical information file will share in case of emergency [40]. Ref. [41] allows user to call 911 and this call can be canceled within 6 s. |

|

| Informative |

| Apps allows the user to send prerecorded voice and text messages to police or the selected person [42]. Interactive map provides a list, addresses, and contact number of shelter homes [43]. App provide the shelter details of the region to offer victims temporary emergency shelter by donating one night shelter rent [44]. |

|

| Legal Information |

| User can anonymously communicate with others. Data stored in encrypted form for the sake of security [45]. |

|

| Self-Assessment |

| The app provide relationship assessment questionnaire and user can call 911 through app [46]. The app provides a checklist of safety behaviors such as, which place is safe to go and it may suggest someone from whom survivor can ask for an emergency loan limited to USD 100 [47]. Some law related documents are available to provide awareness regarding domestic violence. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sumra, M.; Asghar, S.; Khan, K.S.; Fernández-Luna, J.M.; Huete, J.F.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A. Smartphone Apps for Domestic Violence Prevention: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075246

Sumra M, Asghar S, Khan KS, Fernández-Luna JM, Huete JF, Bueno-Cavanillas A. Smartphone Apps for Domestic Violence Prevention: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(7):5246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075246

Chicago/Turabian StyleSumra, Mehreen, Sohail Asghar, Khalid S. Khan, Juan M. Fernández-Luna, Juan F. Huete, and Aurora Bueno-Cavanillas. 2023. "Smartphone Apps for Domestic Violence Prevention: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 7: 5246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075246

APA StyleSumra, M., Asghar, S., Khan, K. S., Fernández-Luna, J. M., Huete, J. F., & Bueno-Cavanillas, A. (2023). Smartphone Apps for Domestic Violence Prevention: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075246