Abstract

Common mental health disorders (CMDs) disproportionately affect people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage. Non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as ‘social prescribing’ and new models of care and clinical practice, are becoming increasingly prevalent in primary care. However, little is known about how these interventions work and their impact on socioeconomic inequalities in health. Focusing on people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage, this systematic review aims to: (1) explore the mechanisms by which non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions impact CMD-related health outcomes and inequalities; (2) identify the barriers to, and facilitators of, their implementation in primary care. This study is a systematic review of qualitative studies. Six bibliographic databases were searched (Medline, ASSIA, CINAHL, Embase, PsycInfo and Scopus) and additional grey literature sources were screened. The included studies were thematically analysed. Twenty-two studies were included, and three themes were identified: (1) agency; (2) social connections; (3) socioeconomic environment. The interventions were experienced as being positive for mental health when people felt a sense of agency and social connection. The barriers to effectiveness and engagement included socioeconomic deprivation and underfunding of community sector organisations. If non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions for CMDs are to avoid widening health inequalities, key socioeconomic barriers to their accessibility and implementation must be addressed.

1. Introduction

The treatment of common mental health disorders (CMDs) such as depression and anxiety form a significant part of the primary care workload. In the United Kingdom (UK), 40% of general practice (GP) appointments have a mental health component [], and in many high-income countries, most people with a mental health problem are seen only in primary care [,,].

The association between socioeconomic disadvantage and CMDs is well established []. Low income, debt, unemployment, and low social class are all associated with higher rates of mental health problems, and those experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage suffer disproportionately from CMD-related adverse health outcomes [,,,]. In addition to experiencing higher rates of CMDs, there is evidence that people living with socioeconomic disadvantage are less able to access and benefit from the treatments for these difficulties [].

Medications such as antidepressants are sometimes effective in the management of CMDs. However, there are growing concerns about the over-prescription or inappropriate use of pharmaceutical interventions [,]. Antidepressant prescribing has increased over the past three decades—a trend that has outpaced the rise in CMD prevalence [,]. Given the associations between CMDs and socioeconomic disadvantage, there are concerns that the overreliance on pharmaceutical treatments may be ineffective and result in the medicalisation of the distress that represents a normal reaction to adverse social and economic conditions []. In the UK, certain indicators of socioeconomic disadvantage, such as unemployment, poor housing, or living in an area of deprivation, are associated with higher antidepressant prescription rates (often independent of a diagnosis of depression) [,,], but poorer access to primary care consultations and other treatments, such as talking therapies [,,].

Non-pharmaceutical interventions represent alternative treatment options for mental distress. Psychological ‘talking’ therapies have become widely embedded in primary care; for example, England’s National Health Service Improving Access to Psychological Treatment (IAPT) service []. The IAPT service has been thoroughly evaluated and found to lead to improvements in depression and anxiety; however, there is also evidence that less advantaged patients struggle to access IAPT services [].

A range of new non-pharmaceutical options for treating CMDs in primary care are now also being introduced. In the UK, ‘social prescribing’, which aims to address the social determinants of mental ill health, is being formally embedded within primary care []. Social prescribing enables people to access a range of support, such as housing and financial advice, bereavement support, and arts activities []. Primary care professionals can refer directly to community services, but most often social prescribing involves link workers, whose role is to connect patients with sources of support in the community [,]. New methods of clinical practice have also been introduced in some areas; for example, integrating clinical psychologists within general practice teams []. In addition, ‘new models of care’ for mental health were introduced in NHS England’s Five Year Forward review []; these aim to improve care for CMDs by, for example, integrating primary and secondary services.

Non-pharmaceutical interventions are increasingly prevalent in primary care practice. Health inequalities and mental ill health both currently represent key policy objectives in the UK and other high-income countries, particularly post-COVID-19 [,]. For these reasons, it is important to review and synthesise the qualitative studies to identify the potential mechanisms by which primary care interventions improve the mental health of people living with socioeconomic disadvantage, as well as the facilitators and barriers affecting people’s engagement with these interventions. A focus on the experiences of people living with socioeconomic disadvantage is necessary to facilitate the design of effective services, to help improve access for marginalised groups, and to mitigate the risk that the interventions may increase health inequalities. This systematic review was undertaken alongside a quantitative review that aimed to synthesise the evidence for the effects of non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions on CMDs in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups []. The quantitative data was extracted on to a range of CMD-related health outcomes, including anxiety and depression, distress, wellbeing, self-reported mental health, and healthcare utilisation for CMDs. Together, the review findings will guide the commission of more equitable mental health services.

Focusing on people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage, this qualitative systematic review aims to: (1) explore the mechanisms by which non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions impact CMD-related health outcomes and inequalities; (2) identify barriers and facilitators to the implementation of non-pharmaceutical CMD interventions in primary care.

2. Methods

The full methodology has been previously described in the published protocol []. The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021281166) []. The methods are reported in accordance with the ‘ENTREQ’ statement for enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research [].

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

The following databases were searched from inception until 1 June 2021: Medline; ASSIA; CINAHL; Embase; PsycInfo; and Scopus (example search strategy in Supplementary File S1). In addition, the resource list of the Social Prescribing Network [], the Social Interventions Research and Evaluations Network [], and third sector websites were purposefully searched for relevant articles. Backwards and forwards citation chaining of the included studies was undertaken and the relevant systematic reviews were assessed.

2.2. Screening and Selection

Following de-deduplication, the titles and abstracts were screened, and the potentially relevant full texts were assessed for eligibility (see Table 1). One reviewer screened each record, and a second reviewer checked a random 10% sample at both stages of the screening process. Screening conflicts were resolved via discussion and adjudication by a third reviewer.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

Socioeconomic disadvantage was assessed according to individual-level socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., income, employment status) or aggregate area-level measures of deprivation (e.g., Index of Multiple Deprivation score).

Any interventions meeting our stated inclusion criteria were included and we did not exclude any interventions based on an assessment by the authors of the evidence base behind any given intervention.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Appraisal

The data extraction and quality appraisal were undertaken by one reviewer and checked in full by another. A modified version of the relevant CASP tool was used to quality appraise the included studies [].

2.4. Thematic Synthesis

Thomas and Harden’s [] three-stage approach to thematic synthesis was used in the data analysis. Using the NVIVO software [], the text from the findings sections of each study was coded line by line and then grouped into descriptive themes according to the similarities and differences. The analytical themes were initially generated by KB through a reflection and return to the original data. They were adapted iteratively on discussion with the wider team until consensus was achieved.

3. Results

3.1. Findings from Systematic Searches

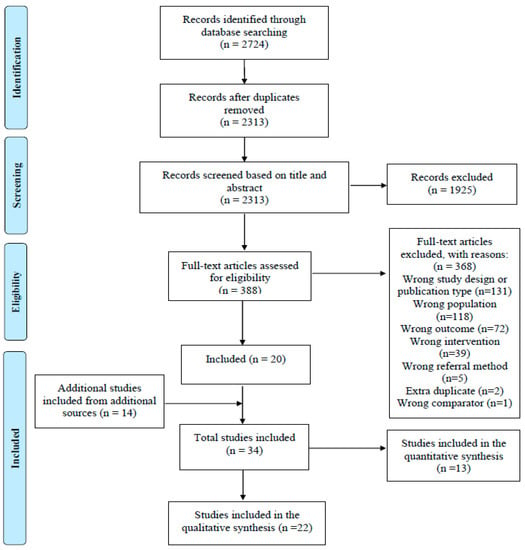

Following de-duplication, a total of 2313 studies were identified from the six databases. After screening, 22 qualitative studies met the inclusion criteria (including five employing mixed methods). The characteristics of included studies are shown in. A PRISMA diagram detailing the search and selection process is displayed in Figure 1 [].

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram [].

Sixteen studies were rated as being high quality using CASP, as well as three medium and three low. Twelve studies were set in England, six in Scotland, one in Ireland, two in Canada, and one in the United States.

None of the studies focused exclusively on people living with CMDs. Instead, they involved wider groups of service users (such as people living with long-term conditions, multimorbidity, ‘complex needs’, or ‘unmet social needs’) that included some people living with CMDs—most commonly anxiety and depression.

Eighteen studies took place in an area of socioeconomic deprivation. Two studies involved the majority of participants being described as low income, one involved participants who were recipients of Medicaid services in the United States of America (US), and one involved a citizens advice service predominantly accessed by people with financial or employment issues.

Nineteen studies involved social prescribing interventions, of which thirteen involved link workers. Two studies involved new methods of clinical practice, both designed to integrate depression care within the management of long-term conditions. One concerned a programme of Behavioural Activation delivered by practice nurses; the other was a pilot intervention of psychological wellbeing practitioners acting as case managers alongside practice nurses. One study involved a new model of care: a large-scale system redesign to deliver integrated care for those with complex needs on Medicaid in the US (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies (* FGD = Focus Group Discussion).

Individuals participating in an intervention will be referred to as ‘people’ or ‘service users’; those working to directly deliver the intervention as ‘providers’, and healthcare professionals as ‘HCPs’.

3.2. Findings from Thematic Analysis

Three themes emerged:

- Agency

- Social connections

- Socioeconomic environment

All three themes can be understood as mechanisms by which non-pharmaceutical interventions impact upon CMD-related health outcomes and inequalities. Each encompasses both the facilitators of, and barriers to, people accessing and engaging with the interventions.

3.2.1. Theme 1: Agency

Agency is broadly understood as individuals having power to make choices and to act on them. The interventions helped people feel that they were able to make their own choices, act independently, and affect change, which was experienced as being positive for their mental health.

Sense of Control and Choice

People described the benefits from the sense of control and choice they experienced when engaging with the interventions in which they were given the opportunity to choose activities and dictate the nature and pace of their engagement [,,,,,,]. For example, a service user taking part in a community hub project explained:

“You can come in here [community hub—LifeRooms] for say 10 minutes, 20 minutes, half an hour… you are in charge of what you’re doing. I think it’s really really important and just that little bit of control can make you feel on top of the world”.[]

“Being able to take an active role in decision making was contrasted with interactions with HCPs that often felt more prescriptive and less collaborative”.[,,]

Confidence, Motivation and Purpose

Many people felt that their involvement in the interventions had increased their confidence, particularly in social interactions and physical activity [,,,,,,,]. Motivation levels also increased during the interventions [,,], while some people reported a new sense of purpose [,,,,]. This often occurred against a backdrop of previous feelings of worthlessness: “so this is kind of giving me a feeling of, you know, you’re not useless” [].

Understanding of Health and Self-Management

Some people felt that the interventions allowed them to gain a better understanding of their own conditions, such as enabling the identification of patterns and triggers of spells of poor mental health [,,,,,]. This improved understanding was often discussed in parallel with the development of condition-management [,,,,,,,]; for example, the recognition of mood patterns, allowing for better communication of needs []. Some interventions improved the insights and coping strategies for both mental and physical health conditions [,,,]. Indeed, a number of people had gained insights into the links between their physical and mental health, both in terms of how physical health impacted upon mental health (e.g., recurrent urinary tract infections contributing to low mood) [,], as well as vice versa (e.g., effect of emotional eating on diabetes control) [].

Functioning and Achieving Goals

People felt that their involvement in the interventions helped them to structure their days, develop routine, and achieve daily activities and functions [,,,,,,]: “I am out of bed, I am dressed, depending on the day whether I’m able to cope with the shower, but certainly washed, dressed and today I am out the house, I am here” []. Managing everyday tasks could help people regain a sense of normality, which for some was seen as central to ‘recovery’ []. Some of the interventions resulted in enjoyment, relaxation, and respite from other life challenges [,,,,]. Several people felt able to look towards wider long-term goals—most commonly education and employment [,,,,,,]. Support from the providers played an important role in this: “An’ I’m contemplating maybe college next year, but I actually feel safe in the fact o’ doing that because I know I’ve got [the link worker] helping me” [].

Improved control, confidence, purpose, motivation, self-management of health, and functioning can all be understood as contributing to individuals gaining or regaining a sense of agency—the power to make choices, and to act on them. However, for some people, factors hindering a sense of agency acted as barriers to accessing and engaging with the interventions. Poor health and a lack of awareness around the interventions curtailed people’s power to make choices and act upon them, thereby acting as barriers to their sense of agency (see below).

Health Conditions

Some people who would have otherwise engaged in the interventions felt unable to do so due to their health [,,,]: “I want to do stuff but my body won’t let me” []. This included physical health conditions [,], as well as the symptoms of CMDs, such as low energy associated with depression:

“You get the days where you are feeling dead down and you can’t be bothered…There are things I want to do, but over these last few months I just haven’t had the energy.”.[]

Lack of Awareness

Many people did not know about the interventions or understand why they had been referred, which may have prevented them from making informed choices about their engagement [,,,]. This was also commented on by GPs: “they [patients] still, similar to me, to begin with, don’t really understand the idea of social prescribing” [].

3.2.2. Theme 2: Social Connections

The interventions helped people to connect with others, to feel cared for, and to feel less alone.

Information Sharing

The benefits of information sharing were discussed by the service users, HCPs, and providers. Information sharing was facilitated by the providers working in teams alongside the HCPs in the general practice setting [,,], as well as administrative aids—such as advice workers having access to medical records in order to help the service users with application forms []. The HCPs widely valued the intervention providers’ expertise on social interventions as being beneficial to holistic care [,,,,,]. For the service users, information sharing helped them feel their care was joined-up:

“I think it’s a good idea that they should know that you’ve got a bit of depression because when I go in there and she says your blood sugar, I said well, I’ve been a bad boy, I’ve eaten this, that and the other, she shouldn’t start saying, oh, what are you doing that for?”.[]

Positive Relationships

Their relationships with the intervention providers, and the social prescribing link workers in particular, were frequently described as being central to people’s experiences of the intervention. People reported that the providers listened to them, understood them, and cared about them [,,,,,,,,,,,,]. The perception that the providers had time to spend with them was contrasted with medical consultations, who frequently felt rushed [,,,]. Accepting and non-judgemental attitudes were particularly valued [,,,,,]:

“Another thing that I find for which I’m very grateful and surprised is how understanding people here are. It’s about one of the very few places that I feel welcome and respected as I am”.[]

Indeed, a couple of service users viewed their relationship with the providers in terms of companionship that was otherwise lacking for them [,]. The providers’ practical support, such as accompanying service users to activities and appointments, was also widely appreciated [,,,,,,,,,].

The GP/patient relationship also facilitated engagement with the interventions, with several people feeling encouraged to participate in the interventions recommended by a trusted GP [,]. Others emphasised the acceptability of the interventions that took place in the setting of a GP surgery. For some, this was due to convenience [,], but was more commonly discussed as being due to privacy and the avoidance of the stigma related to mental health difficulties [,,,]:

“It’s very much more acceptable for our patients to see someone regarding mood at the practice as opposed to going externally to see a counsellor… more acceptable when it’s seen to be the nurse… People like to hang hooks on names, patients don’t generally go round talking about their depression, but you do hear them going around all the time talking about their diabetes or angina or whatever”.[]

However, such preferences were not universal, and some participants preferred keeping physical health management settings separate from mental health (Knowles et al., 2015).

Difficulties in Relationships with Providers

A small number of people described difficulties in their relationships with the intervention providers [,,]. Strong service user/provider relationships, when disrupted, could lead to disengagement, with service users feeling abandoned when the providers moved on [,]:

“My first worker left, I used to see her a lot. I was put onto another one… Now she’s left and they’ve put me onto somebody else who I’ve never seen…I just feel as though I’ve been let down… pushed to one side”.[]

Dependency on link workers, given the intense nature of the support role, was also identified as a difficulty by link workers themselves [].

3.2.3. Theme 3: Socioeconomic Environment

Some of the interventions enabled improvements in people’s socioeconomic circumstances, which was experienced as being positive for mental health. For others, their socioeconomic circumstances presented a barrier to engaging with the interventions. On an organisational level, the socioeconomic environment could present a barrier to implementation.

Help with Social Needs

People found help with finances—including benefits, debts, and returning to work—extremely valuable [,,,,]. Some described the palpable impact this had on their mental health:

“Whatever money I owed like electricity and TV licence was in my mind always eating me from inside. I sorted out that and it just changed so many things … It changed my attitude, it changed my behaviour and it changed my mood … I am not depressed like before”.[]

Some of the link workers viewed helping with social needs as a central aspect of their role []. GPs also described adapting their practice to better cater to the needs outside of the biomedical model [,]:

“My consultation had to move away from this sort of biomedical model of depression…and see the patient a bit more in the wider family and community… Talk about appetite or sleep leads quite smoothly to antidepressants and sleeping tablets but doesn’t move to social prescribing… So I had to change my consultation style … I find it easier now”.[]

Socioeconomic Deprivation

Low income could act as a barrier to engagement with interventions. One study reported that a social prescribing intervention was viewed as being similar to schemes designed to remove people from receiving state benefits, and thus was seen as a potential threat to welfare entitlement:

“Now there is a big drive to get people off benefits—rightly or wrongly—so they are reluctant to go anywhere where it says Job Centre Plus. I think they (patients) saw a little bit of similarity between social prescribing and Discover Opportunities and that put the brakes on”.[]

Low incomes made accessing the interventions problematic [,]. Poor transport access in rural areas was described as contributing to a “cycle of deprivation” for those who could not travel outside of the area for work, compounding their mental health problems []. Others were put off accessing the suggested interventions that were not affordable or did not offer enough free sessions [,].

Social Needs beyond HCP Capacity

Some HCPs did not view social concerns as being part of their role “Is it really my job to refer people to the Citizens Advice Bureau? Is it really my job to tell them about their weight? They’re social things …we don’t really have the expertise” []. More often, HCPs felt they did not have the power or capacity to address wider social problems and were already overwhelmed by other demands [,]. This included a sense that social problems were too complicated and that it was too late for HCPs to fix them: “We have a problem with underage drinking … as doctors I’m not sure that there’s hellish much that I can do, by the time people walk in through my door it’s probably too late” []. HCPs also expressed a lack of awareness of social sources of support [,,,].

Feeling Failed by the System

For several people, feeling failed, let down, and excluded by both the healthcare and welfare systems affected their willingness to engage in the interventions [,]. People described experiences of being ‘passed’ around between doctors’ appointments and the Job Centre (UK government offices providing advice for the unemployed) without feeling heard or helped by either, causing hesitancy to engage further in the system:

“There’s nobody for the likes o’ me. You’re just left tae, I don’t know, vegetate… No, the system’s totally wrong… As I say, they told me… “You’ll never work again.” So, where do you get the hope fae? Where dae you get the faith fae?”.[]

Sustainability and Funding

People felt concerned about the short-term nature of the interventions, and what would happen afterwards [,,,], including concerns about being “hung out to dry” when the programme ended []. For one service user, worries about the programme’s sustainability became a new source of mental distress: “I’ve got a big fear that [the Links Worker Programme] stops. That is actually part o’ my anxiety” []. Funding problems were also frequently discussed as a barrier to implementation—mostly by the providers and HCPs in relation to community sector programmes [,,,]. This was closely tied to sustainability, in that the programmes were not guaranteed to last due to constantly “chasing funding” []. One GP discussed the risk of unstable programmes (often shutting down quickly due to short-term funding) leading to GPs’ reluctance to refer people only for them to experience further disappointment by the system [].

Link workers were also described as having stretched capacity in their roles, as well as being limited in their ability to refer onwards to community organisations due to their reduced availability [,]. There were resulting concerns about the quality of the services provided due to the demand being unmatched by resources:

“I’m seeing more and more of the time, the resources demand, the stretch on organisations in terms of the amount of people that seem to be getting referred to these organisations now. And I think potentially the quality of service of these organisations could suffer”.[]

The above concerns were frequently discussed in the context of austerity [,,,]—an economic policy, prominent in the UK from 2010, that cut social spending and increased taxation, resulting in reduced public and community services [].

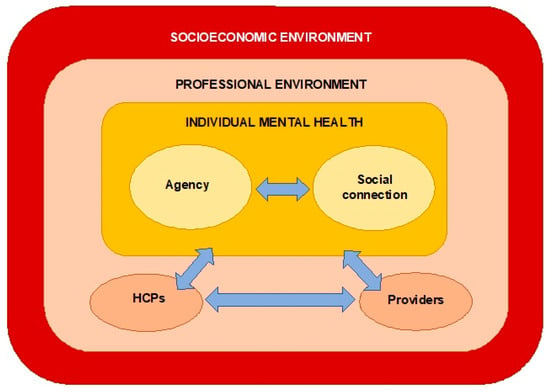

3.2.4. Interactions between Themes

Figure 2 illustrates the interactions between the three themes. Agency and social connection are understood as being central mechanisms by which people experienced positive mental health outcomes from the interventions. These two mechanisms can be interpreted as being mutually reinforcing: it is likely that individuals’ sense of agency helped to enable social connection, and vice versa. These mechanisms can be understood as being influenced by the ‘professional environment’ (for example, the roles of HCPs, and the professional relationships between the HCPs and providers), which in turn created barriers and facilitators to positive outcomes. At the wider level, the outcomes were influenced by the socioeconomic environment in which the individuals and the healthcare system operate—with poverty, organisational funding and resources affecting both the professional environment and individual mental health. These interactions suggest that people’s agency (ability to make choices and act independently) was influenced by socioeconomic forces, which shape the choices available to people.

Figure 2.

Interactions between themes.

4. Discussion

Non-pharmaceutical approaches to treating and managing CMDs are increasingly prevalent in primary care. People living with socioeconomic disadvantage experience the highest burden of CMDs, and it is therefore vital that these interventions are acceptable and accessible to this group of service users. Our review aimed to explore the mechanisms, barriers, and facilitators by which non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions impact on CMD-related health outcomes for people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage. Twenty-two papers were included in the review, and three themes emerged from the analysis.

The interventions were experienced as being positive for mental health when people felt they could gain a sense of agency and social connection. People living with CMDs in more deprived areas are also more likely to have more complex health needs, including comorbidities []. Many of the interventions included in this review had benefits beyond improving mental health, resulting in the improved management of physical comorbidities. The key barriers to positive outcomes included individual socioeconomic disadvantage affecting accessibility and wider socioeconomic factors affecting implementation.

Our findings on the importance of agency and social connections support those of the previous reviews of social prescribing interventions across a range of patient groups [,,,,]. For example, Tierney et al. [] draw on theories of ‘social capital’ and ‘patient activation’ as mechanisms by which link worker programmes had an impact, whilst Pescheny et al. [] emphasise ‘self concepts and feelings’, ‘day-to-day functioning’, and ‘social interactions’ as key elements of service users’ experiences of social prescribing. Moreover, several of the primary studies reviewed found value in the ‘self-determination theory’ to explain the intervention impacts based on the psychological need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness [,]. The importance of emphasizing basic human relationships and social connection in supporting people’s health and social needs also echoes previous work by Cottam [] on re-imagining the models of healthcare and the welfare state.

In contrast with previous evidence, our review finds explicit evidence of the wider socioeconomic environment affecting intervention impact—going beyond the level of the individual. On an individual level, we find that the support to address social needs was important for improving mental health, whilst socioeconomic disadvantage negatively affected engagement. On a wider level, we find that the resource constraints linked to austerity affected the ability of the community sector organisations to implement interventions. Link workers were overstretched, often unable to refer people on due to the demand being unmatched by resources, and funding for programmes was discussed as being short term and unpredictable. It is worth noting that in the context of mental ill health and pre-existing disadvantage, uncertainty around funding is likely to be particularly harmful for this group of service users.

Given the majority of studies reviewed were set in the UK after 2010, the context of austerity represents a crucial backdrop to these findings. The instability of the community sector, as well as people’s sense of being failed by ‘the system’, should arguably be understood through a wider structural lens. This lens takes into account how political and economic choices, and the distribution of power and resources in society, have a significant effect on people’s health. Our review supports the idea that addressing the mental health needs of those at the sharp end of severe social and economic inequality requires a decided emphasis on the structural determinants of health [].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to synthesise the literature on the experiences of non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions for CMDs in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. The findings provide useful insights into the mechanisms by which non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions may improve people’s mental health, as well as the facilitators of, and barriers to, people’s engagement with these types of intervention. A strength of using a qualitative design was that we were able to uncover some of the complexities involved in the delivery and experiences of interventions in this space [].

Our study has a number of limitations. Due to resource constraints, and a desire for a generalisability of findings across similar primary healthcare settings, only studies conducted in high-income countries were included. We may have missed valuable insights into non-pharmaceutical interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Important findings from studies in other languages may also have been missed due to only including literature published in English.

The current evidence base is also limited. While we set out to explore a range of non-pharmaceutical interventions, most of the included studies focused on social prescribing, making it harder to draw conclusions about new models of care and new methods of clinical practice. Although all of the studies involved one or more participants with CMDs, none of them focused exclusively on CMDs—instead involving people with a wider range of health and social needs. This limits our ability to draw conclusions about CMDs specifically, with the findings likely to instead be more generalised. Similarly, although all of the studies involved a majority of participants living with socioeconomic disadvantage, several also included a minority of participants who were not, which may have diluted our findings with regard to this specific subgroup. All of the studies focused on the experiences of people who had actively engaged with interventions. We are therefore likely to be missing important perspectives on the barriers to access and engagement, which was often mentioned as a limitation by the authors themselves [,]. Finally, we originally intended to review several dimensions of inequality, as described in the protocol, but focused on socioeconomic disadvantage only due to resource constraints.

4.2. Implications

Our review underlines several gaps in the literature on non-pharmaceutical interventions for CMDs in primary care. Firstly, we recommend a need for more research involving participants who did not engage with interventions, or those who only engaged briefly. This would help to discern more accurately the barriers to access and engagement, and further inform policies to reduce inequalities in this area.

Secondly, we recommend further research exploring other dimensions of disadvantage and marginalisation, beyond a socioeconomic focus. Given that significant inequalities in mental health exist according to gender [], race and ethnicity [,,], age [], disability status [], and sexual orientation [], a better understanding of the mechanisms, barriers, and facilitators of non-pharmaceutical interventions in a range of marginalised groups is needed.

Thirdly, we recommend further research focusing on new models of care and new methods of clinical practice for CMDs in primary care. An improved understanding of these types of interventions is likely to become increasingly necessary as their prominence increases.

Our review emphasises that interventions that are difficult to access for those most in need of them, which risks widening health inequalities. We also bring to light systemic problems with funding for the community sector organisations—an integral part of delivery for the interventions reviewed—linked to austerity. Finally, the review highlights a general lack of awareness of non-pharmaceutical mental health interventions in primary care. The implications for policy are summarised as follows:

- If existing inequalities are to be seriously addressed, the experiences of those living with socioeconomic disadvantage must become a central part of decision-making processes.

- For interventions to be effective, the community sector organisations they rely upon need to be adequately and sustainably funded., This is likely to require pressure on policy makers to provide sustained funding for community organisations that provide non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions for CMDs.

- Raising awareness of non-pharmaceutical interventions among both healthcare professionals and service users is likely to be beneficial for engagement and implementation.

5. Conclusions

As non-pharmaceutical interventions for mental health become more embedded in UK primary care, there is a need to consider the experiences of people living with socioeconomic disadvantage as a central part of policy decision-making, in order to avoid widening the existing health inequalities. Future research should focus on exploring the barriers to accessibility for those who have not engaged with interventions, as well as exploring the experiences of other disadvantaged and marginalised groups. There is also a need for sustainable funding of the community sector organisations that are frequently relied upon to deliver such interventions. Addressing the mental health needs of those affected by social and economic inequality requires a decided focus on the structural determinants of health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph20075237/s1, File S1: Example search strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.M.W., K.H.T. and S.S.; Methodology: J.M.W., K.H.T., S.S., L.M.T., M.S. and A.S.; Analysis and interpretation K.B, J.M.W., L.M.T., A.S., M.S., R.G., C.E., S.S. and K.H.T. K.B. wrote the manuscript and all authors have been included in the drafting and revision process. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the NIHR Research Capability Funding (RCF) from the NHS North of England Care System Support (NECS). S.S. is supported by Health Education England (HEE) and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) through an Integrated Clinical Academic Lecturer Fellowship (Ref CA-CL-2018-04-ST2-010) and RCF funding, NHS North of England Care System Support (NECS). This project is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) for the Northeast and North Cumbria (NENC). K.B. undertook the research as part of her Academic Foundation Programme (employed by the NHS, Health Education England). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mind. Mental Health in Primary Care: A Briefing for Clinical Commissioning Groups; Mind: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, T.; Burns, T.; Garland, C.; Greenwood, N.; Smith, P. Are specialist mental health services being targeted on the most needy patients? The effects of setting up special services in general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2000, 50, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reilly, S.; Planner, C.; Hann, M.; Reeves, D.; Nazareth, I.; Lester, H. The role of primary care in service provision for people with severe mental illness in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundquist, J.; Ohlsson, H.; Sundquist, K.; Kendler, K.S. Common adult psychiatric disorders in Swedish primary care where most mental health patients are treated. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Social Determinants of Mental Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R.; Bhugra, D.; Bebbington, P.; Brugha, T.; Farrell, M.; Coid, J.; Fryers, T.; Weich, S.; Singleton, N.; Meltzer, H. Debt, income and mental disorder in the general population. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryers, T.; Melzer, D.; Jenkins, R.; Brugha, T. The distribution of the common mental disorders: Social inequalities in Europe. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2005, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S.; Bebbington, P.; Jenkins, R.; Brugha, T. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014; NHS Digital: Leeds, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.; Balfour, R.; Bell, R.; Marmot, M. Social determinants of mental health. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K.; Stafford, M.; Fisher, R.; Docherty, M.; Deeny, S. Inequalities in Health Care for People with Depression and/or Anxiety; The Health Foundation UK: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, I.; Woodward, L. The medicalisation of unhappiness? The management of mental distress in primary care. In Constructions of Health and Illness; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, C. Decolonizing Global Mental Health: The Psychiatrization of the Majority World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, R.; Roberts, A.; Ariti, C.; Bardsley, M. Focus On: Antidepressant Prescribing; The Health Foundation & Nuffield Trust: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bogowicz, P.; Curtis, H.J.; Walker, A.J.; Cowen, P.; Geddes, J.; Goldacre, B. Trends and variation in antidepressant prescribing in English primary care. BJGP Open 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C. The Psychiatrization of Poverty: Rethinking the Mental Health-Poverty Nexus. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2015, 9, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, P.; Ashworth, M.; Tylee, A. Ethnic density, physical illness, social deprivation and antidepressant prescribing in primary care: Ecological study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 193, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopfert, A.; Deeny, S.R.; Fisher, R.; Stafford, M. Primary care consultation length by deprivation and multimorbidity in England: An observational study using electronic patient records. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, e185–e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K. Inequalities in English NHS Talking Therapy Services: What Can the Data Tell Us?: Examining NHS Digital Annual Reports to Look at Deprivation; The Health Foundation: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, S.; Kellett, S.; Simmonds-Buckley, M.; Stockton, D.; Bradbury, A.; Delgadillo, J. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) in the United Kingdom: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 10-years of practice-based evidence. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 60, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonker, L.; Thwaites, R.; Fisher, S. Patient referral from primary care to psychological therapy services: A cohort study. Fam. Pract. 2020, 37, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drinkwater, C.; Wildman, J.; Moffatt, S. Social prescribing. BMJ 2019, 364, l1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husk, K.; Blockley, K.; Lovell, R.; Bethel, A.; Lang, I.; Byng, R.; Garside, R. What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.C.H.; Mahtani, K.; Turk, A.; Tierney, S. Social Prescribing in National Health Service Primary Care: What Are the Ethical Considerations? Milbank Q. 2021, 99, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood-Everett, S.; Schlosser, A.; Lavis, P.; Howell, S.; Ibison, J. Clinical Psychology in Primary Care—How Can We Afford to Be without It?: A Briefing for Clinical Commissioners and Integrated Care Systems; British Psychological Society: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, C.; Taggart, H.; Charles, A. Mental Health and New Models of Care: Lessons from the Vanguards; King’s Fund: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NHS. NHS Long Term Plan. Available online: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Stevens, S.; Pritchard, A. Third Phase of NHS Response to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/07/20200731-Phase-3-letter-final-1.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Tanner, L.M.; Wildman, J.M.; Stoniute, A.; Still, M.; Bernard, K.; Green, R.; Eastaugh, C.H.; Thomson, K.H.; Sowden, S. Non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions to improve mental health in deprived populations: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2023, bjgp.2022.0343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, L.; Sowden, S.; Still, M.; Thomson, K.; Bambra, C.; Wildman, J. Which Non-Pharmaceutical Primary Care Interventions Reduce Inequalities in Common Mental Health Disorders? A Protocol for a Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIHR. Which Non-Pharmaceutical Primary Care Interventions Reduce Inequalities in Common Mental Health Disorders? A Protocol for a Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies (PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021281166) 2021. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=281166 (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Tong, A.; Flemming, K.; McInnes, E.; Oliver, S. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTRE. Q. BMC Med. Res. Methodology 2012, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Social Prescribing Network. Resources. Available online: https://www.socialprescribingnetwork.com/resources (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- SIREN (Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network). Make Health Whole. Integrating Care. Improving Lives. Available online: https://makehealthwhole.org/resource/siren-social-interventions-research-evaluation-network/ (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Long, H.A.; French, D.P.; Brooks, J.M. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res. Methods Med. Health Sci. 2020, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International. Best Qualitative Data Analysis Software for Researchers|NVivo. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Altman, D.G.; Booth, A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertotti, M.; Frostick, C.; Hutt, P.; Sohanpal, R.; Carnes, D. A realist evaluation of social prescribing: An exploration into the context and mechanisms underpinning a pathway linking primary care with the voluntary sector. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2018, 19, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, S.; Rayner, J.; Pinto, A.D.; Mulligan, K.; Cole, D.C. Using self-determination theory to understand the social prescribing process: A qualitative study. BJGP Open 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnes, D.; Sohanpal, R.; Matthur, R.; Homer, K.; Hull, S.; Bertotti, M.; Frostick, C.; Netuveli, G.; Tong, J.-J.; Findlay, G.; et al. City and Hackney Social Prescribing Service: Evaluation Report; QMUL: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chng, N.R.; Hawkins, K.; Fitzpatrick, B.; O’Donnell, C.; Mackenzie, M.; Wyke, S.; Mercer, S.W. Implementing social prescribing in primary care in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation: Process evaluation of the ‘Deep End’ community links worker programme. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, e912–e920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedli, L.; Themessl-Huber, M.; Butchart, M. Evaluation of Dundee Equally Well Sources of Support: Social Prescribing in Maryfield; Evaluation Report Four; Dundee Partnership Prescribing: Dundee, Scotland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, K.; Sharples, A.; Jackson, D. Citizens Advice Bureaux in general practice: An illuminative evaluation. Health Soc. Care Community 2000, 8, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanlon, P.; Gray, C.M.; Chng, N.R.; Mercer, S.W. Does Self-Determination Theory help explain the impact of social prescribing? A qualitative analysis of patients’ experiences of the Glasgow ‘Deep-End’ Community Links Worker Intervention. Chronic Illn. 2021, 17, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.M.; Giebel, C.; Morasae, E.K.; Rotheram, C.; Mathieson, V.; Ward, D.; Reynolds, V.; Price, A.; Bristow, K.; Kullu, C. Social prescribing for people with mental health needs living in disadvantaged communities: The Life Rooms model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, B.; Connolly, D.; Clyne, B.; Boland, F.; O’Donnell, P.; Shea, E.O.; Smith, S.M. Primary care-based link workers providing social prescribing to improve health and social care outcomes for people with multimorbidity in socially deprived areas (the LinkMM trial): Pilot study for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J. Multimorb. Comorbidity 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S.E.; Chew-Graham, C.; Adeyemi, I.; Coupe, N.; Coventry, P.A. Managing depression in people with multimorbidity: A qualitative evaluation of an integrated collaborative care model. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, S.; Gask, L. ‘Getting back to normal’: The added value of an art-based programme in promoting ‘recovery’ for common but chronic mental health problems. Chronic Illn. 2012, 8, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffatt, S.; Steer, M.; Lawson, S.; Penn, L.; O’Brien, N. Link Worker social prescribing to improve health and well-being for people with long-term conditions: Qualitative study of service user perceptions. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, K.; Hsiung, S.; Bhatti, S.; Rehel, J.; Rayner, J. Social Prescribing in Ontario: Final Report; AHC: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, K.; Walton, E.; Burton, C. Steps to benefit from social prescription: A qualitative interview study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e36–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescheny, J.; Randhawa, G.; Pappas, Y. Patient uptake and adherence to social prescribing: A qualitative study. BJGP Open 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siantz, E.; Henwood, B.; Gilmer, T. Patient Experience With a Large-Scale Integrated Behavioral Health and Primary Care Initiative: A Qualitative Study. Fam. Syst. Health 2020, 38, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, J. The Deep End Advice Worker Project: Embedding an Advice Worker in General Practice Settings; GCPH: Glasgow, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Skivington, K.; Smith, M.; Chng, N.R.; Mackenzie, M.; Wyke, S.; Mercer, S.W. Delivering a primary care-based social prescribing initiative: A qualitative study of the benefits and challenges. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 68, e487–e494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, L.A.D.; Ekers, D.; Chew-Graham, C.A. Feasibility of training practice nurses to deliver a psychosocial intervention within a collaborative care framework for people with depression and long-term conditions. BMC Nurs. 2016, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.M.; Cornish, F.; Kerr, S. Front-line perspectives on ‘joined-up’ working relationships: A qualitative study of social prescribing in the west of Scotland. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildman, J.M.; Moffatt, S.; Steer, M.; Laing, K.; Penn, L.; O’Brien, N. Service-users’ perspectives of link worker social prescribing: A qualitative follow-up study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildman, J.M.; Moffatt, S.; Penn, L.; O’Brien, N.; Steer, M.; Hill, C. Link workers’ perspectives on factors enabling and preventing client engagement with social prescribing. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckler, D.; Reeves, A.; Loopstra, R.; Karanikolos, M.; McKee, M. Austerity and health: The impact in the UK and Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescheny, J.; Pappas, Y.; Randhawa, G. Facilitators and barriers of implementing and delivering social prescribing services: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescheny, J.; Randhawa, G.; Pappas, Y. The impact of social prescribing services on service users: A systematic review of the evidence. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tierney, S.; Wong, G.; Roberts, N.; Boylan, A.-M.; Park, S.; Abrams, R.; Reeve, J.; Williams, V.; Mahtani, K.R. Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: A realist review. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidovic, D.; Reinhardt, G.Y.; Hammerton, C. Can Social Prescribing Foster Individual and Community Well-Being? A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottam, H. Radical Help: How We Can Remake the Relationships between Us and Revolutionise the Welfare State; Virago: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, J.M.; Goldner, E.M.; Waraich, P.; Hsu, L. Prevalence and Incidence Studies of Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Can. J. Psychiatry 2006, 51, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentell, T.; Shumway, M.; Snowden, L. Access to mental health treatment by English language proficiency and race/ethnicity. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.; Campbell, C.; Cornish, F. African-Caribbean interactions with mental health services in the UK: Experiences and expectations of exclusion as (re)productive of health inequalities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, T.; Sewell, H.; Shapiro, G.; Ashraf, F. Mental health inequalities facing U.K. minority ethnic populations: Causal factors and solutions. J. Pyschol. Issues Organ. Cult. 2013, 3, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, E.; Hatton, C. Contribution of socioeconomic position to health inequalities of British children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2007, 112, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semlyen, J.; King, M.; Varney, J.; Hagger-Johnson, G. Sexual orientation and symptoms of common mental disorder or low wellbeing: Combined meta-analysis of 12 UK population health surveys. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).