Like Riding a Roller Coaster: University Teachers’ Emotional Experiences Dealing with Student Plagiarism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizing Plagiarism

2.2. Teacher’s Cognition

2.3. Teacher’s Emotions

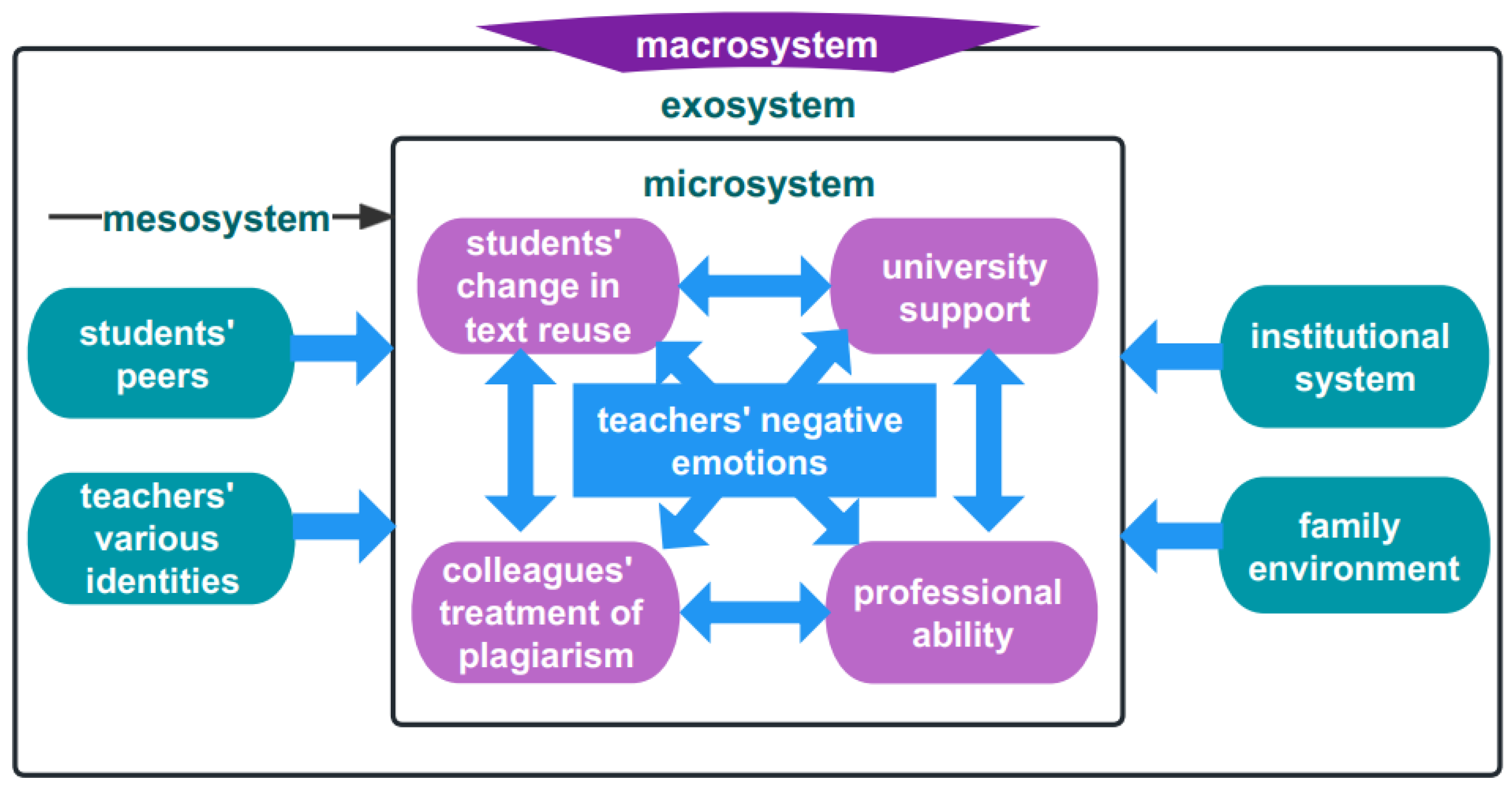

2.4. Theoretical Framework

- Do Chinese teachers of English experience any emotional challenges in their interactions with ecological systems when addressing student plagiarism in the context of academic writing?

- Do any emotional changes occur during these interactions? If so, what factors affect the emotional changes that occur in teachers when viewed from an ecological perspective?

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Participants

3.2. Research Methods

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Ethical Considerations

3.6. Trustworthiness and Limitations

4. Findings

4.1. Emotional Challenges in Different Ecological Systems

4.1.1. Microsystems

4.1.2. Mesosystems

4.1.3. Exosystems

4.1.4. Macrosystem

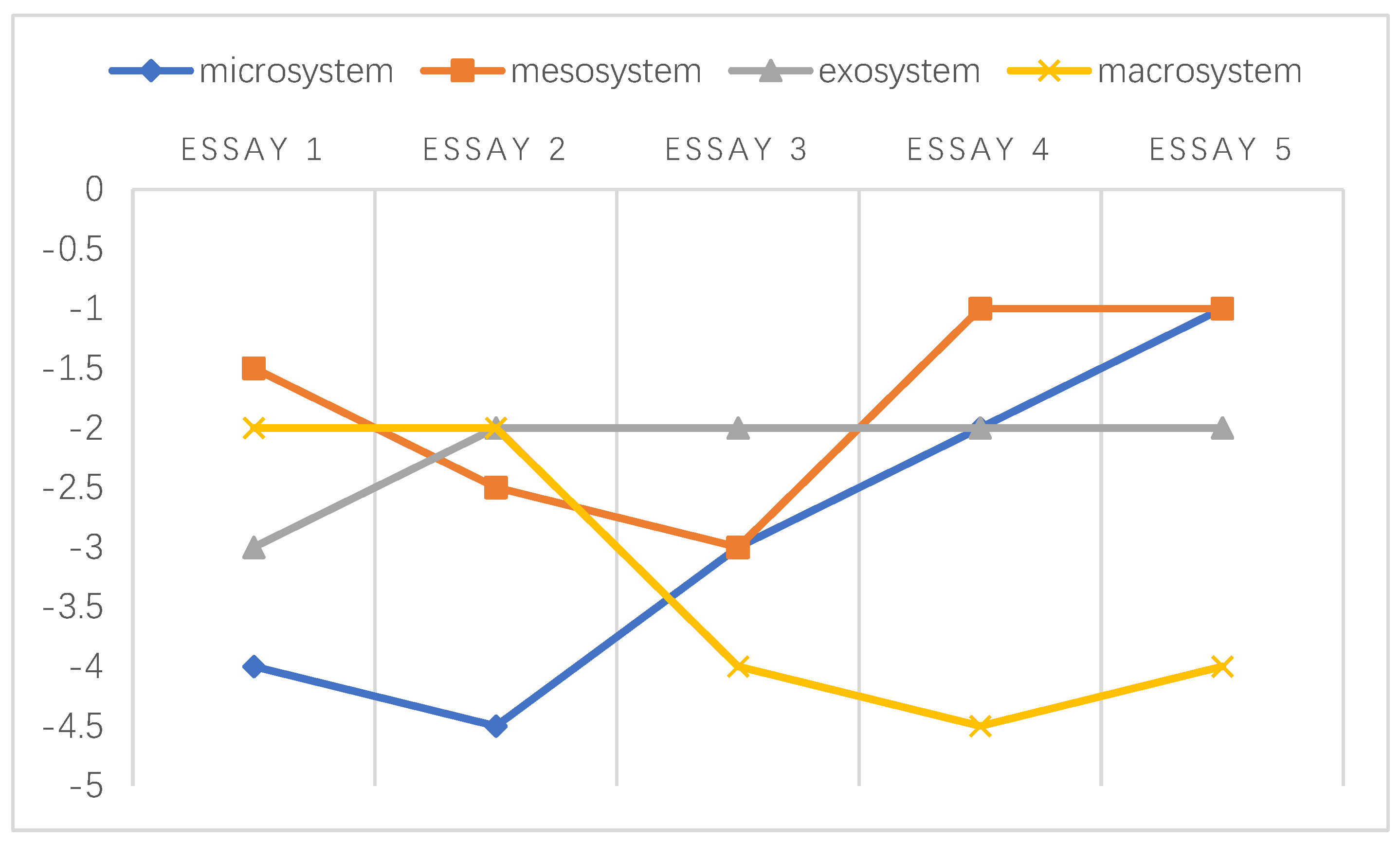

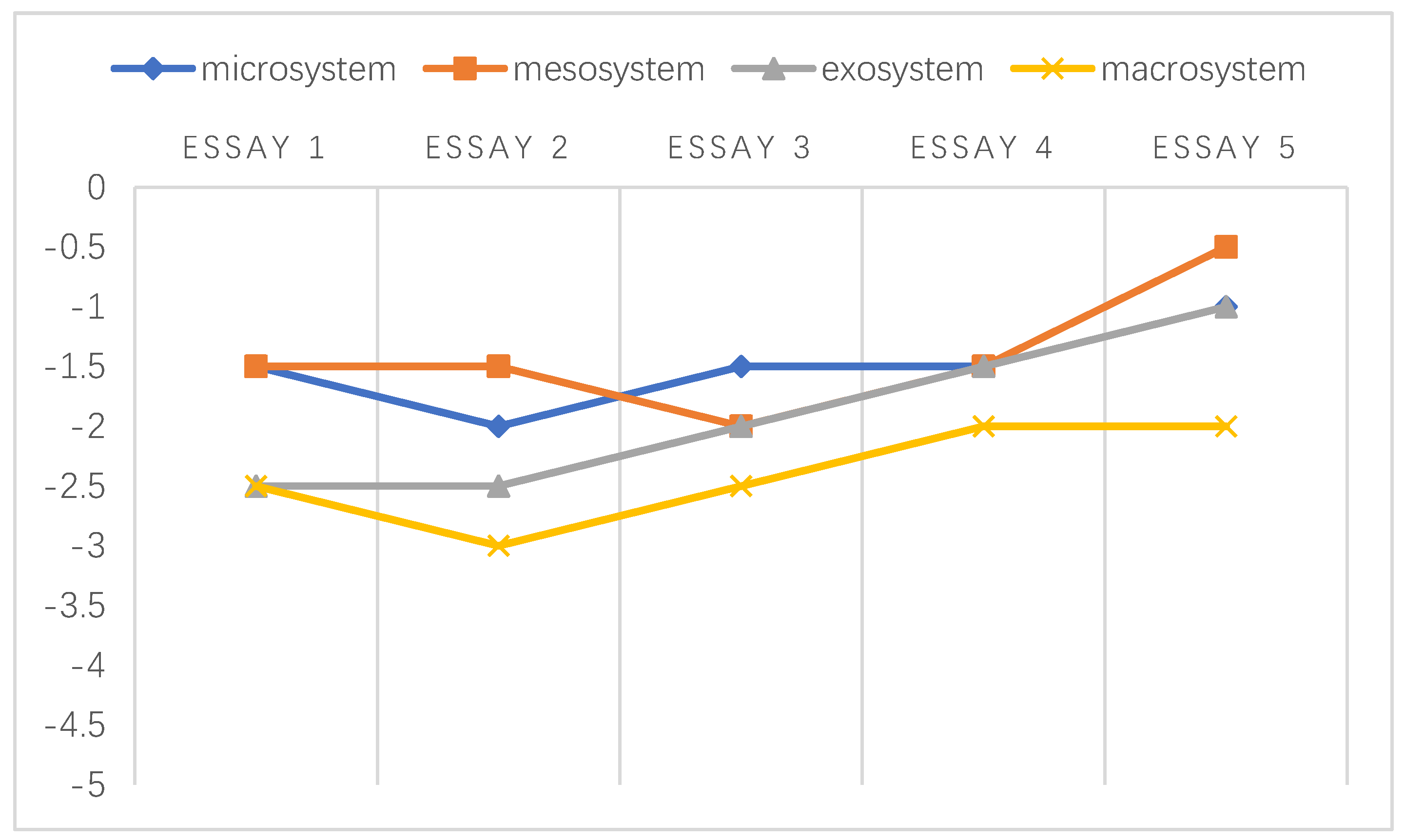

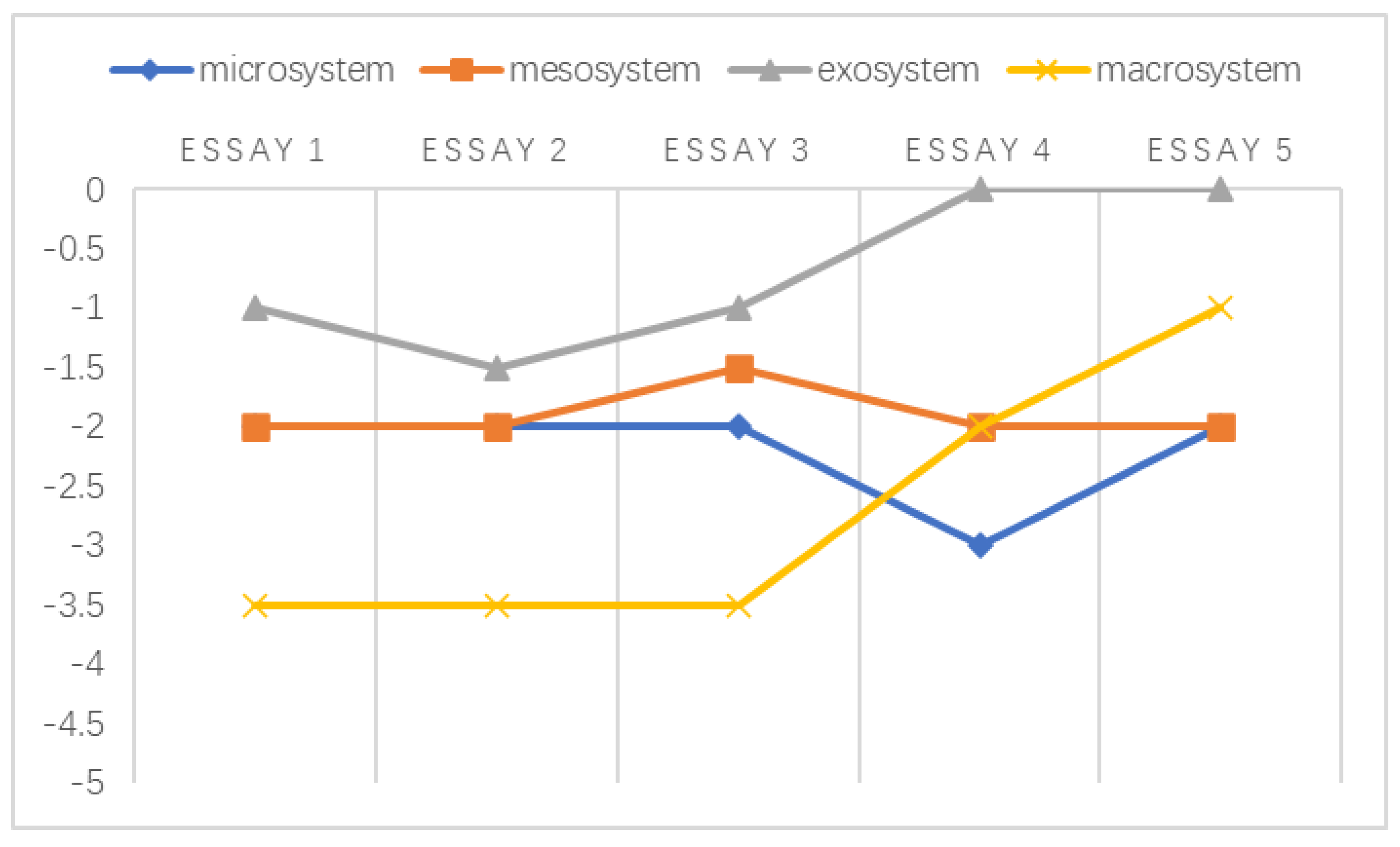

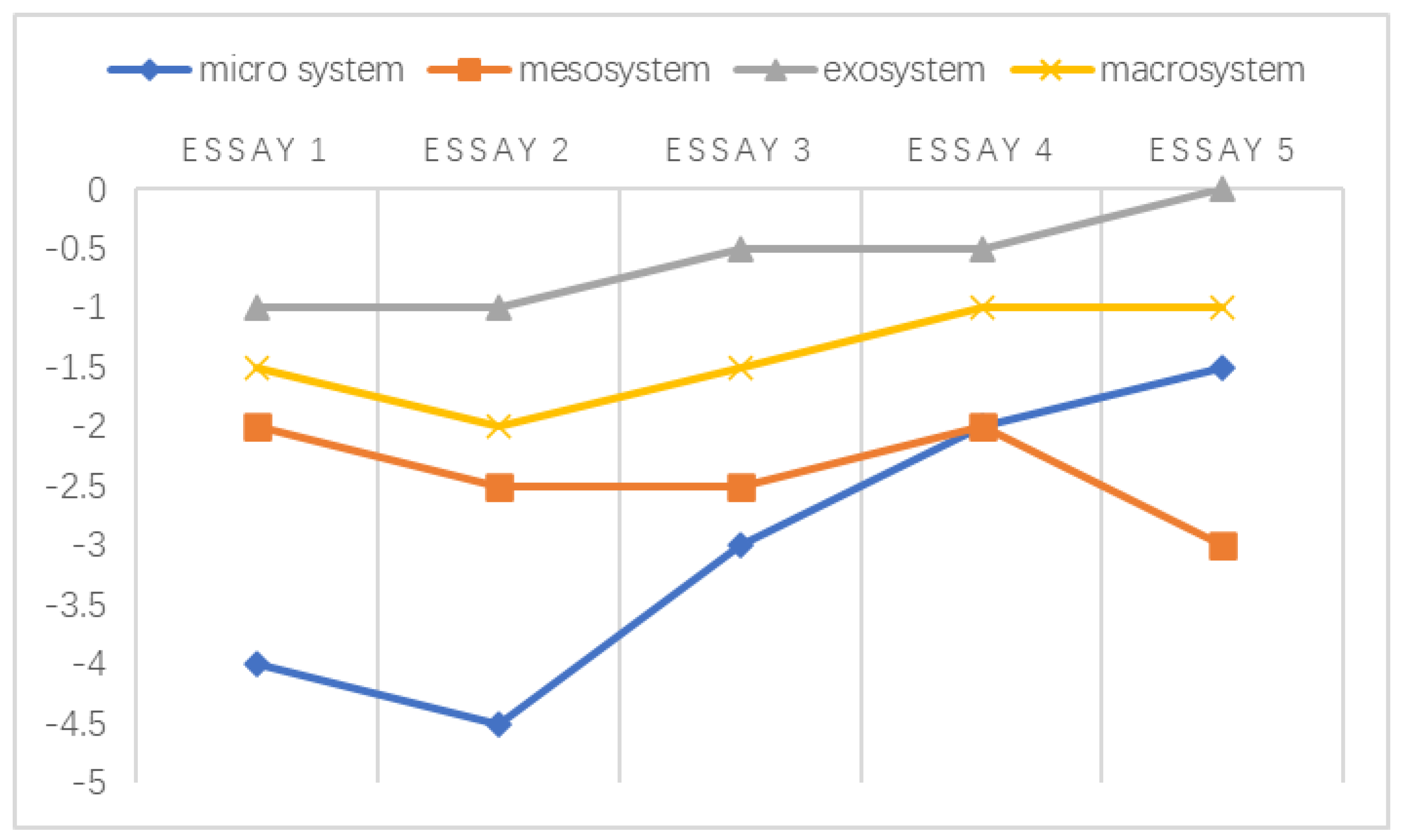

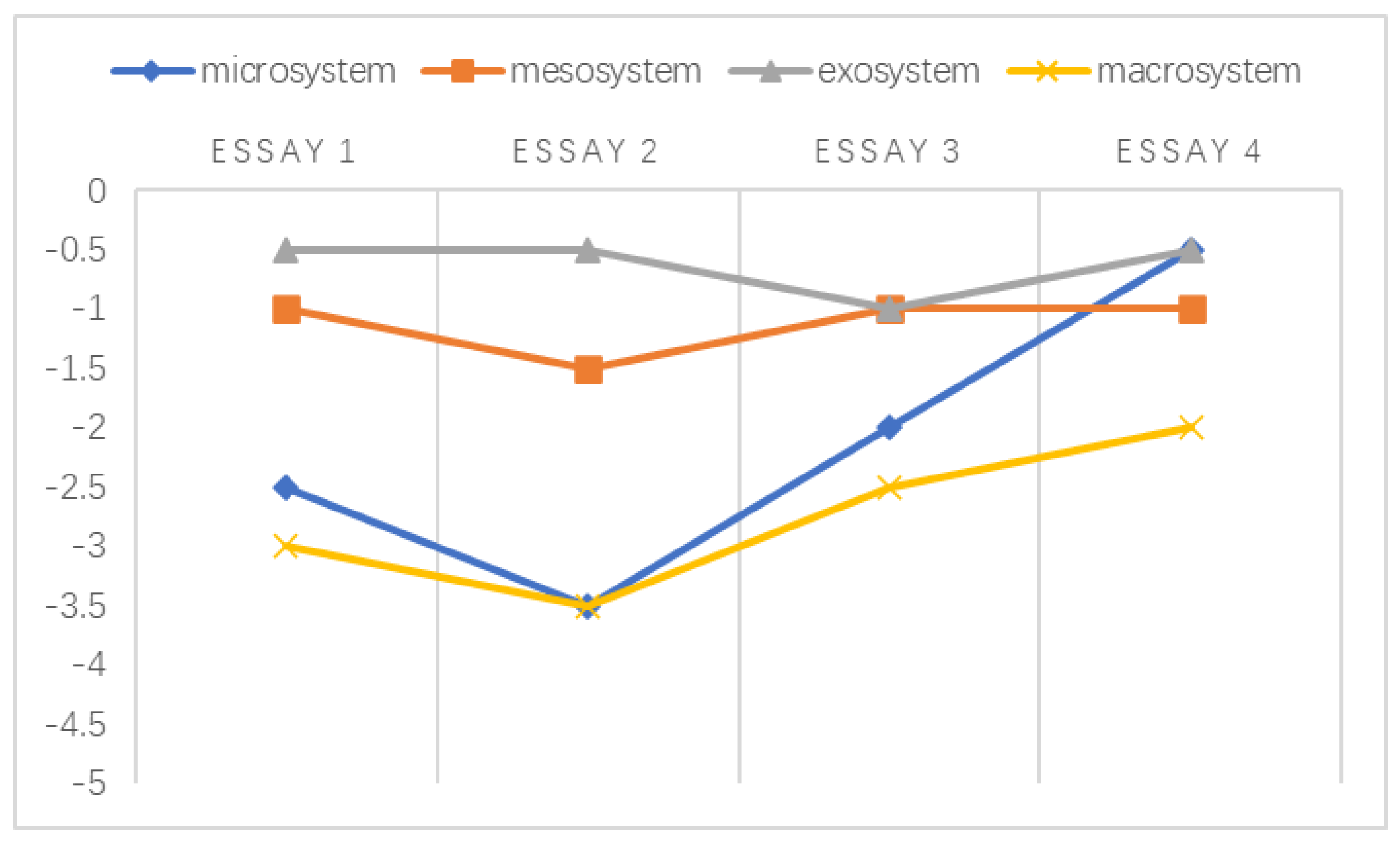

4.2. Changes in the Emotional Challenges Faced by Teachers in the Chronosystem

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sutherland-Smith, W. Pandora’s box: Academic perceptions of student plagiarism in writing. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2005, 4, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowerdew, J.; Li, Y. Plagiarism and second language writing in electronic age. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2007, 27, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Lei, J. Plagiarism in English academic writing: A comparison of Chinese university teachers’ and students’ understandings and stances. System 2016, 56, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazilatfar, A.M.; Elhambakhsh, S.E.; Allami, H. An investigation of the effects of citation instruction to avoid plagiarism in EFL academic writing assignments. SAGE Open 2018, 8, 2158244018769958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourlay, L.; Deane, J. Loss, responsibility, blame? Staff discourses of student plagiarism. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2012, 49, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehviläinen, S.; Löfström, E.; Nevgi, A. Dealing with plagiarism in the academic community: Emotional engagement and moral distress. High Educ. 2018, 75, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, D.I.; Hong, J.Y. An ecological examination of teachers’ emotions in the school context. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girn, R.; Punch, A.; Jimenez, Y.A. Diagnostic radiography students’ perceptions of working in the clinical environment: A focus on emotional challenges. Radiography 2022, 28, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S. The wellbeing of language teachers in the private sector: An ecological perspective. Lang. Teach. Res. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lin, V.; Kou, X.; Wang, H. Best practices in L2 English source use pedagogy: A thematic review and synthesis of empirical studies. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 19, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasi, A.R.; Graves, B. Academic literacy and plagiarism: Conversations with international graduate students and disciplinary professors. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2008, 7, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorari, D. Teaching to Avoid Plagiarism: How to Promote Good Source Use; Open University Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, S. Teacher Cognition and Language Education: Research and Practice; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2006; Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Academic staff’s perspectives upon student plagiarism: A case study at a university in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2015, 35, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Hu, G. What do academics know and do about plagiarism? An interview study with Chinese university teachers of English. Ethics Behav. 2020, 30, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, J. Staff and student attitudes to plagiarism at University College, Northampton. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, A. Borrowing others’ words: Text, ownership, memory, and plagiarism. TESOL Q. 1996, 30, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Lei, J. Chinese University Students’ Perceptions of Plagiarism. Ethics Behav. 2015, 25, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, C. The use of paraphrase in summary writing: A comparison of L1 and L2 writers. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2006, 15, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. Cultural backgrounds and textual appropriation. Lang. Aware. 2006, 15, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. Reworking the policing of plagiarism. J. Basic Writ. 2017, 36, 78–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H.; Leu, S.; McDonough, K. L2 writers’ use of outside sources and the related challenges. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2019, 38, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S. Cultural constructions of plagiarism in student writing: Teachers’ perceptions and responses. Res. Teach. Engl. 2014, 49, 120–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Shen, Y. Chinese university teachers’ perceptions and practices regarding plagiarism: Knowledge, stance, and intertextual competence. Ethics Behav. 2020, 31, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, J. Plagiarism across cultures: Is there a difference. In Originality, Imitation, and Plagiarism: Teaching Writing in the Digital Age? Eisner, C., Vicinus, M., Eds.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008; pp. 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.; Hu, G. Chinese ESOL lecturers’ stance on plagiarism: Does knowledge matter? ELT J. 2014, 68, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzaanin, E.I. Capturing the emotional experiences of English as a foreign language university teachers: A critical perspective. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. The Interactive Effect of EFL Teachers’ Emotions and Cognitions on Their Pedagogical Practices. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 811721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, L. A narrative case study of Chinese senior high school English teachers’ emotions: An ecological perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 792400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, C.; Xu, Y. I even feel annoyed and angry: Teacher emotional experience in giving feedback on student writing. Assess. Writ. 2021, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, I. A holistic approach to higher education plagiarism: Agency and analysis levels. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2021, 41, 1869–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, G.M.; Darragh, J.J. This worry machine: The impact of executive orders on ELL teachers. TESOL J. 2018, 9, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D.R. Responding to student writing: Teachers’ philosophies and practices. Assess. Writ. 2014, 19, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.K.; Yin, H.B. Teachers’ emotions and professional identity in curriculum reform: A Chinese perspective. J. Educ. Change 2011, 12, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.B. Knife-like mouth and tofu-like heart: Emotion regulation by Chinese teachers in classroom teaching. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.; McCallum, F. Ecological influences on teachers’ work, well-being, and “fitness”. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 43, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yan, C.; Fu, J. Exploring livestream English teaching anxiety in the Chinese context: An ecological perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 111, 103620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Riazi, A. The Routledge Encyclopedia of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed-Methods Research; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benesch, S. Emotions as agency: Feeling rules, emotion labor, and English language teachers’ decision-making. System 2018, 79, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Morley, J. Phrasal intertextuality: The responses of academics from different disciplines to students’ re-use of phrases. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2015, 28, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.Y.F.; Elander, J.; Stupple, E.J.N.; Flay, M. Academics’ understandings of the authorial academic writer: A qualitative analysis of authorial identity. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1468–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.A. How to collect and analyze qualitative data. In Research Methods in Second Language Acquisition: A Practical Guide; Alison, M., Gass, S.M., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 180–200. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gkonou, C.; Miller, E.R. An exploration of language teacher reflection, emotion labor, and emotional capital. TESOL Q. 2021, 55, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, B. Transcription quality. In Handbook of Interview Research; Gubrium, J.F., Holstein, J.A., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 628–649. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mruck, K.; Breuer, F. Subjectivity and reflexivity in qualitative research. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2003, 40, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. Rewriting and paraphrasing source texts in second language writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2012, 21, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In Development in Context: Acting and Thinking in Specific Environments; Wozniak‚, R.H., Fischer, K.W., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M. The importance and benefits of teacher collegiality in schools a literature review. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2021, 46, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G. Teacher Agency. In Encyclopedia of Teacher Education; Peters, M.A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

| Students Taught | Sex | Age | Degree | Years of Teaching | Years of Studying Abroad | University Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | NEM (non-English majors) | F | 29 | Ph.D. | 0.5 | 5 | 985/211 |

| T2 | NEM | M | 44 | Ph.D. candidate | 10 | 0.5 | / |

| T3 | NEM | F | 55 | MA | 31 | 0 | 211 |

| T4 | EM (English majors) | F | 41 | Ph.D. | 10 | 3 | 985/211 |

| T5 | EM | F | 56 | Ph.D. | 29 | 2 | / |

| T6 | EM | M | 36 | Ph.D. | 6 | 6 | 985/211 |

| Research Questions | Opening Coding | Axial Coding | Selective Coding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Do Chinese teachers of English experience any emotional challenges in their interactions with ecological systems when addressing students’ plagiarism in the context of academic writing? | I am frustrated by the need to reemphasize academic integrity in the class. | The negative emotions experienced by teachers in the context of coping with students’ textual appropriation. | Microsystem |

| I feel very angry regarding my colleagues’ lenient treatment of plagiarism. | |||

| I experience self-condemnation when addressing student plagiarism. | |||

| 2-1. Do any emotional changes occur during these interactions? | Bad text copying is a serious issue… I felt sad about the students’ poor writing ethics. (Tx-journal 1)Some work was turned in with little revision. I felt offended. (Tx-journal 2) | Teachers’ negotiations with students became more tense. | Teachers’ emotions became more negative. |

| 2-2. If so, what factors affect the emotional changes that occur in teachers when viewed from an ecological perspective? | Without Turnitin, both teachers and students hardly noticed bad text borrowing. I was sort of discouraged. | Lack of plagiarism detection software | University support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X. Like Riding a Roller Coaster: University Teachers’ Emotional Experiences Dealing with Student Plagiarism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043276

Wang X. Like Riding a Roller Coaster: University Teachers’ Emotional Experiences Dealing with Student Plagiarism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043276

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaojing. 2023. "Like Riding a Roller Coaster: University Teachers’ Emotional Experiences Dealing with Student Plagiarism" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043276

APA StyleWang, X. (2023). Like Riding a Roller Coaster: University Teachers’ Emotional Experiences Dealing with Student Plagiarism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043276