Association between Urban Educational Policies and Migrant Children’s Social Integration in China: Mediated by Psychological Capital

Abstract

:1. Introduction

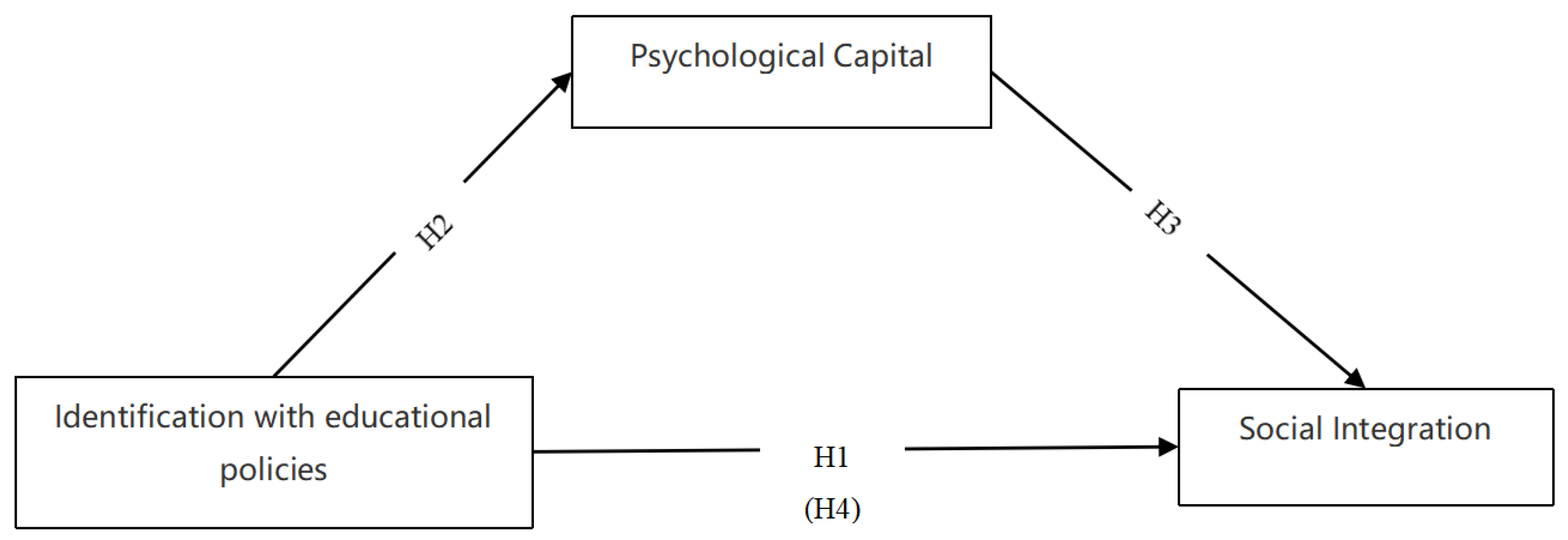

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. The Connotation of Social Integration and Its Influencing Factors

2.2. The Relationship between Social Integration and Migrant Children’s Identification with Educational Policies

2.3. The Relationship between Psychological Capital and Migrant Children’s Identification with Educational Policies

2.4. The Relationship between Migrant Children’s Psychological Capital and Social Integration

3. Research Design and Measurement of Variables

3.1. Research Samples and Data Collection

3.2. Variable Definition and Measurement

3.2.1. Migrant Children’s Psychological Capital (PC)

3.2.2. Migrant Children’s Social Integration (SI)

3.2.3. Migrant Children’s Identification with Educational Policies (IEP)

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Correlation Analysis

4.2. Regression Analysis

4.2.1. Analysis of the Regression of Migrant Children’s Identification with Educational Policies on Their Social Integration

4.2.2. Analysis of the Regression of Migrant Children’s Identification with Educational Policies on Their Psychological Capital

4.2.3. Testing of the Mediating Effects of Psychological Capital between Identification with Educational Policies and Social Integration

Testing of the Mediating Effects of Psychological Capital between Identification and Identification with Educational Policies

Testing of the Mediating Effects of Psychological Capital between Acculturation and Identification with Educational Policies

Testing of the Mediating Effects of Psychological Capital between Psychological Integration and Identification with Educational Policies

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Education Development Statistics Bulletin in 2020. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_fztjgb/202108/t20210827_555004.html (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Park, R.E. Human migration and the marginal man. Am. J. Sociol. 1928, 33, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, L.; Jaap, D.; Gerbert, K. Immigrant children’s educational achievement in western countries: Origin, destination, and community effects on mathematical performance. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 73, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, B.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Lin, D. Self-esteem, resilience, social support, and acculturative stress as predictors of loneliness in chinese internal migrant children: A model-testing longitudinal study. J. Psychol. 2021, 155, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medari, Z.; Sedmak, M.; Dean, L.; Gornik, B. Integration of migrant children in slovenian schools (la integración de los ni?os migrantes en las escuelas eslovenas). Cul. Edu. 2021, 33, 758–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlobina, A.; Basabe, N.; Paez, D.; Fumham, A. Sociocultural adjustment of immigrants: Universal and group-specific predictors. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 2006, 30, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.M.; Jia, N. Rural dispositions of floating children within the field of Beijing schools: Can disadvantaged rural habitus turn into recognised cultural capital? Brit. J. Sociol. Educ. 2016, 37, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yue, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, A. Choices or constraints: Education of migrant children in urban China. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2020, 39, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Political Psychology, 1st ed.; Jost, J.T., Sidanius, J., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 13, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N.; Knippenberg, A.; Vries, N.D.; Wilke, H. Social identification and permeability of group boundaries. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 18, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canino, S.; Raimo, S.; Boccia, M.; Di Vita, A.; Palermo, L. On the embodiment of social cognition skills: The inner and outer body processing differently contributes to the affective and cognitive theory of mind. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, P.; Williams, R.M. Social integration and longevity: An event history analysis of women’s roles and resilience. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1989, 54, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosswick, W.; Heckmann, F. Integration of migrants: Contribution of local and regional authorities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 28, 168–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Duan, X.; Li, M.; Li, Y. The Relationship between Mindfulness and Social Adaptation among Migrant Children in China: The Sequential Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Resilience. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Zhi, X.; Xu, J.; Yang, P.; Wang, X. Negative impacts of school class segregation on migrant children’s education expectations and the associated mitigating mechanism. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minello, A.; Barban, N. The education expectations of children of immigrants in Italy. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Ss. 2012, 643, 78–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palardy, G.J. High school socioeconomic segregation and student attainment. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 50, 714–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Bianchi, D.; Biasi, V.; Alivernini, F. Social inclusion of immigrant children at school: The impact of group, family and individual characteristics, and the role of proficiency in the national language. Int. J. Inclu. Edu. 2020, 27, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinjans, K.J. Family background and gender differences in educational expectations. Econ. Lett. 2010, 107, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.E.; Field, T.M.; Diego, M.A. Adolescents’ academic expectations and achievement. Adolescence 2001, 36, 795–802. [Google Scholar]

- Hannum, E. Market transition, educational disparities, and family strategies in rural china: New evidence on gender stratification and development. Demography 2005, 42, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max, W. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Lv, C. The influence of migrant children’s identification with the college matriculation policy on their educational expectations. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 963216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, A.H.; Veum, J.R.; Darity, W. The Impact of Psychological and Human Capital on Wages. Econ. Inq. 1997, 35, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.M.; Luthans, F. Relationship between entrepreneurs’ psychological capital and their authentic leadership. JMI 2006, 18, 254–273. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40604537 (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Luthans, F.; Luthans, K.W.; Luthans, B.C. Positive Psychological Capital:beyond human and social capital. Bus. Horizons 2004, 47, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerath, P.; Lynch, J.; Davidson, M. Dimensions of psychological capital in a U.S. suburb and high school: Identities for neoliberal times. Anthropol. Educ. Quart. 2008, 39, 270–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, T. Perceived Social Support, Psychological Capital, and Subjective Well-Being among College Students in the Context of Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Asia-Pacific Edu. Res. 2021, 31, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Dong, Y. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with mental health. Studies Psychol. Behav. 2010, 8, 58–64. Available online: https://psybeh.tjnu.edu.cn/CN/abstract/abstract930.shtml (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Gu, Y.; Tang, T.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W. Sustainable career development of new urban immigrants: A psychological capital perspective. J Cleaner Prod. 2019, 208, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, w.; Lin, X. Relationship between school adjustment and positive psychological characters in floating children. Chin. Mental Hlt. J. 2014, 28, 267–270. Available online: http://www.cmhj.cn/WKD2/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=61ce7fab-c927-481e-a025-804ca0690442 (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Boen, F.; Vanbeselaere, N. Responding to membership of a low-status group: The effects of stability, permeability and individual ability. Group Process. Interg. 2000, 3, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willits, F.K.; Theodori, G.L.; Luloff, A.E. Another look at likert scales. J. Rural Soc. Sci. 2016, 31, 126–139. Available online: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol31/iss3/6 (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.; Walumbwa, F.; Li, W. The psychological capital of Chinese workers: Exploring the relationship with performance. Manage. Organ. Rev. 2005, 15, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Rana-Deuba, A. Acculturation and adaptation revisited. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1999, 30, 422–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and The Adolescent Self-Image, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T.; Smelser, N. Economy and Society: A Study in the Integration of Economic, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K. Social inclusion of migrant children in the school field: An ethnographic approach. J. Sch. Stud. 2012, 9, 91–95+122. Available online: https://zhjy.cbpt.cnki.net/WKH/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=46b4da97-16b2-48dd-ad0e-d0c9466928be# (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Liu, Q.; Feng, L. Structure, current situation and influencing factors of migrant children’s social integration. J. Chin. You. Soc. Sci. 2014, 14, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Kennedy, A. The measurement of sociocultural adaptation. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 1999, 23, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, C.; Zhu, Z.; Lin, Q. Family migration and social integration of migrants: Evidence from Wuhan Metropolitan area, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hao, Q. Residential isolation in the process of rapid urbanization: An empirical study from Shanghai. Academic Mon. 2014, 46, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sun, L. Social support networks and adaptive behaviour choice: A social adaptation model for migrant children in China based on grounded theory. Child. Youth Serv. 2020, 113, 104940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Zhao, D.; Yang, W.; Tian, X. The relationship between adolescent family functioning and prosocial behavior: A moderated mediation model. Psy. Deve. Educ. 2022, 38, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, T.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Y. Peer attachment and proactive socialization behavior: The moderating role of social intelligence. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N (%) | Distribution of Samples | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZJ | FJ | JS | SD | LN | HN | GD | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 813 (45.9) | |||||||

| Male | 957 (54.1) | |||||||

| Type of household mobility | ||||||||

| “Rural-urban” mobility | 1405 (79.4) | 278 | 225 | 186 | 156 | 174 | 183 | 203 |

| “Town-town” mobility | 365 (20.6) | 75 | 80 | 66 | 35 | 39 | 38 | 32 |

| School type | ||||||||

| Voluntary school (migrant children) | 441 (24.9) | 65 | 30 | 55 | 39 | 36 | 58 | 59 |

| Local public school | 1329 (75.1) | 218 | 135 | 138 | 147 | 101 | 113 | 102 |

| Father’s level of education | ||||||||

| High school level or below | 1625 (95.6) | 203 | 277 | 247 | 209 | 184 | 266 | 239 |

| Undergraduate degree or above | 75 (4.4) | 11 | 13 | 8 | 12 | 17 | 9 | 5 |

| Duration of residence | ||||||||

| 1–3 years | 352 (19.9) | 74 | 52 | 33 | 27 | 42 | 64 | 76 |

| 3–5 years | 322 (18.2) | 75 | 67 | 60 | 45 | 39 | 15 | 21 |

| ≥5 years | 1096 (61.9) | 183 | 128 | 141 | 159 | 224 | 115 | 146 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) IEP | 1 | |||||||

| (2) Self-Confidence | 0.686 ** | 1 | ||||||

| (3) Optimistic | 0.849 ** | 0.755 * | 1 | |||||

| (4) Resilience | 0.784 ** | 0.737 ** | 0.813 ** | 1 | ||||

| (5) Hope | 0.767 ** | 0.755 ** | 0.793 ** | 0.827 ** | 1 | |||

| (6) Identification | 0.896 ** | 0.664 ** | 0.796 ** | 0.749 ** | 0.724 ** | 1 | ||

| (7) Acculturation | 0.874 ** | 0.649 ** | 0.764 ** | 0.669 ** | 0.654 ** | 0.834 ** | 1 | |

| (8) PI | 0.600 ** | 0.599 ** | 0.644 ** | 0.637 ** | 0.599 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.416 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Identification | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Sex | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.004 | 0.029 | 0.052 | 0.022 |

| Type of household mobility | 0.085 * | 0.043 | 0.095 * | 0.049 | 0.124 * | 0.054 | 0.115 * | 0.048 |

| Type of School | −0.030 | −0.048 | 0.051 | 0.054 | 0.057 | 0.052 | 0.062 | 0.055 * |

| Father’s Level of Education | 0.065 | 0.043 | 0.089 * | 0.050 | 0.123 * | 0.057 * | 0.131 * | 0.054 |

| Duration of Residence | 0.208 * | 0.028 | 0.062 | 0.004 | 0.044 | 0.002 | 0.050 | 0.001 |

| IEP | 0.777 ** | 0.737 ** | 0.732 ** | 0.782 ** | ||||

| Self-Confidence | 0.689 ** | 0.121 ** | ||||||

| Optimistic | 0.735 ** | 0.144 ** | ||||||

| Resilience | 0.689 ** | 0.158 ** | ||||||

| Hope | 0.663 ** | 0.102 ** | ||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.596 | 0.821 | 0.697 | 0.820 | 0.661 | 0.824 | 0.615 | 0.819 |

| F | 137.654 ** | 200.114 ** | 194.068 ** | 207.231 ** | 169.194 ** | 206.830 ** | 149.408 ** | 200.960 ** |

| Variables | Acculturation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Sex | 0.081 * | 0.036 | 0.081 | 0.040 | 0.076 | 0.039 | 0.116 * | 0.038 |

| Type of household mobility | 0.088 * | 0.049 | 0.099 * | 0.055 * | 0.130 | 0.052 | 0.121 * | 0.051 |

| School type | −0.033 | −0.016 | −0.010 | −0.007 | −0.004 * | −0.001 | −0.008 | −0.001 |

| Father’s Level of Education | 0.077 | 0.057 | 0.101 * | 0.063 | 0.132 * | 0.059 | 0.139 * | 0.058 * |

| Duration of Residence | 0.129 * | 0.037 * | 0.011 | 0.067 * | 0.031 | 0.077 | 0.026 | 0.030 |

| IEP | 0.709 ** | 0.699 ** | 0.698 ** | 0.715 ** | ||||

| Self-Confidence | 0.654 ** | 0.131 ** | ||||||

| Optimistic | 0.683 ** | 0.113* | ||||||

| Resilience | 0.597 ** | 0.121 * | ||||||

| Hope | 0.572 ** | 0.105 * | ||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.608 | 0.789 | 0.680 | 0.794 | 0.592 | 0.791 | 0.563 | 0.791 |

| F | 338.447 ** | 713.918 ** | 451.717 ** | 699.618 ** | 307.280 ** | 684.365 ** | 277.910 ** | 684.796 ** |

| Variables | PI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Sex | 0.078 | 0.042 | −0.076 | 0.051 | 0.063 | 0.040 | 0.107 * | 0.055 |

| Type of household mobility | 0.102 * | 0.134 * | 0.093 * | −0.121 * | 0.066 | 0.114 * | 0.075 | 0.122 * |

| Type of School | −0.013 | −0.001 | −0.007 | −0.008 | −0.012 | 0.009 | −0.016 | −0.011 |

| Father’s Level of Education | 0.085 | 0.101 * | 0.062 | −0.086 | 0.031 | −0.077 | −0.023 | 0.078 |

| Duration of Residence | 0.073 | 0.060 * | 0.063 | 0.098 * | 0.080 | 0.109 * | 0.074 | 0.110 * |

| IEP | 0.583 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.552 ** | ||||

| Self-Confidence | 0.642 ** | 0.221 * | ||||||

| Optimistic | 0.685 ** | 0.327 ** | ||||||

| Resilience | 0.647 ** | 0.273 ** | ||||||

| Hope | 0.622 ** | 0.224 ** | ||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.634 | 0.724 | 0.699 | 0.731 | 0.674 | 0.730 | 0.650 | 0.725 |

| F | 311.001 ** | 825.824 ** | 473.668 ** | 824.866 ** | 400.963 ** | 845.162 ** | 332.368 ** | 818.248 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, C.; Yang, P.; Xu, J.; Sun, J.; Ming, Y.; Zhi, X.; Wang, X. Association between Urban Educational Policies and Migrant Children’s Social Integration in China: Mediated by Psychological Capital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043047

Lv C, Yang P, Xu J, Sun J, Ming Y, Zhi X, Wang X. Association between Urban Educational Policies and Migrant Children’s Social Integration in China: Mediated by Psychological Capital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043047

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Cixian, Peijin Yang, Jingjing Xu, Jia Sun, Yuelong Ming, Xiaotong Zhi, and Xinghua Wang. 2023. "Association between Urban Educational Policies and Migrant Children’s Social Integration in China: Mediated by Psychological Capital" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043047

APA StyleLv, C., Yang, P., Xu, J., Sun, J., Ming, Y., Zhi, X., & Wang, X. (2023). Association between Urban Educational Policies and Migrant Children’s Social Integration in China: Mediated by Psychological Capital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043047