The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Depression among Chinese Junior High School Students: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Cognitive Failures and Mindfulness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Meaning in Life and Depression in Junior High School Students

1.2. Cognitive Failures as a Mediator

1.3. Mindfulness as a Moderator

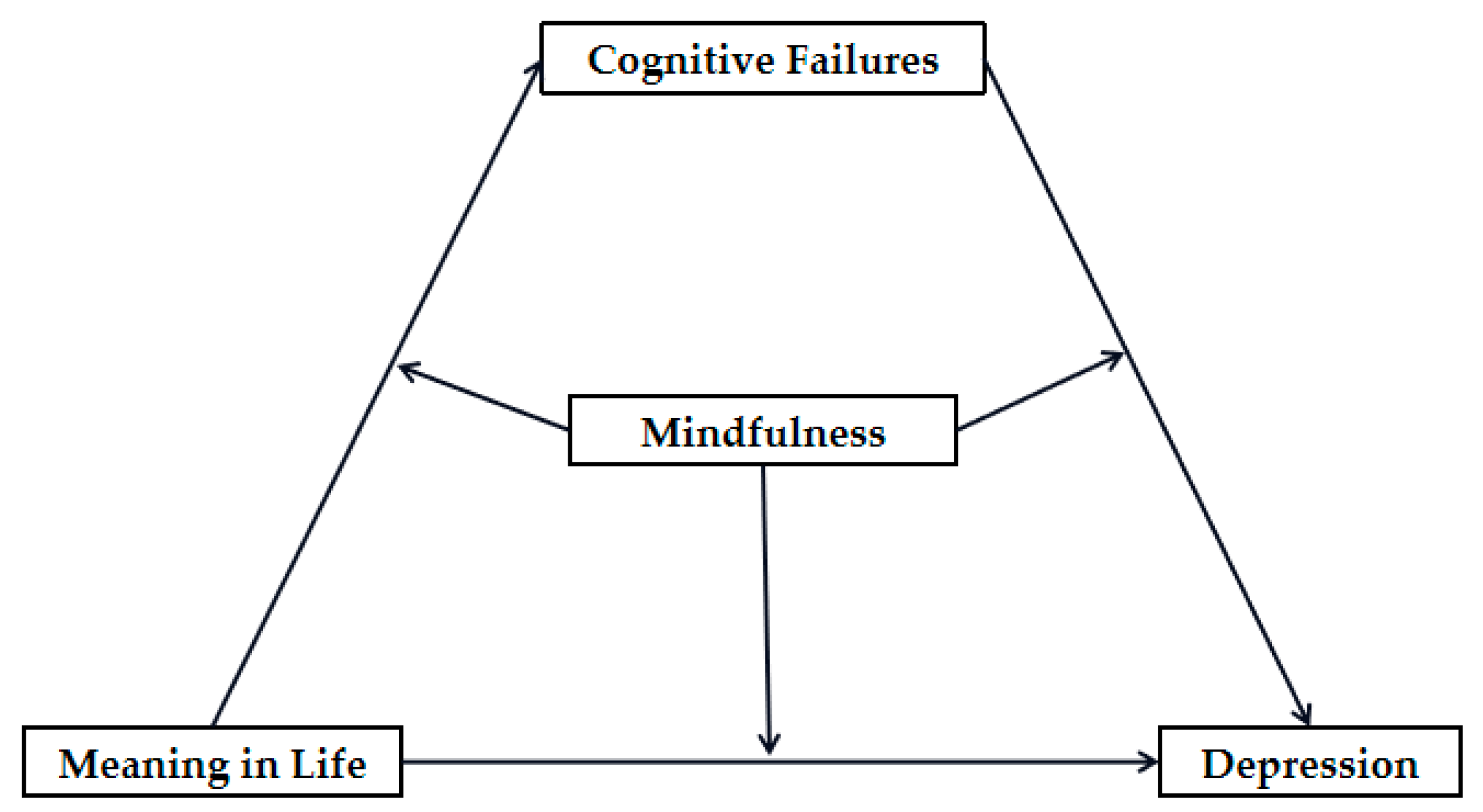

1.4. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Meaning in Life

2.3.2. Depression

2.3.3. Cognitive Failures

2.3.4. Mindfulness

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

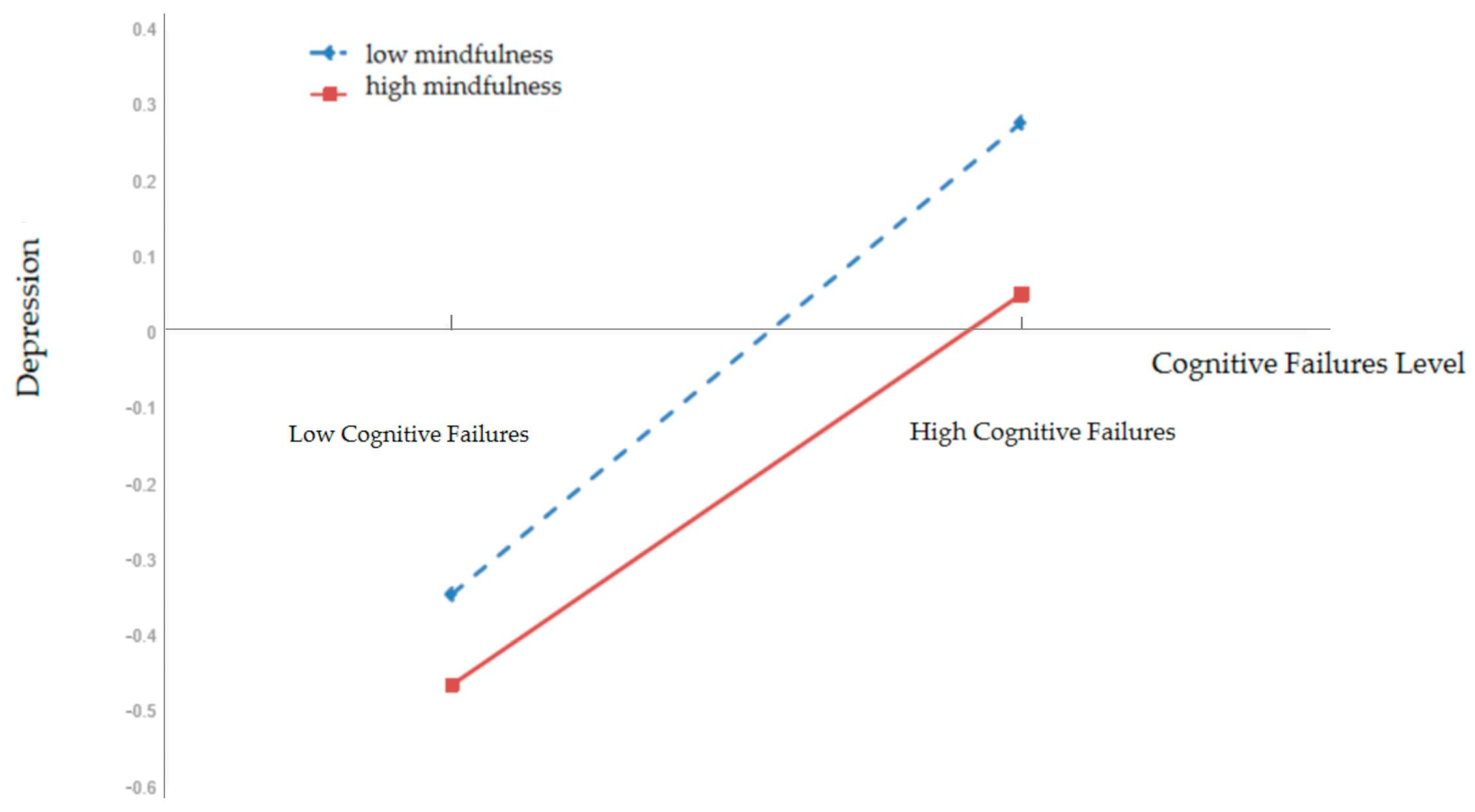

3.3. Testing for Moderated Mediation Effect

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Depression

4.2. The Mediating Role of Cognitive Failures

4.3. The Moderating Role of Mindfulness

4.4. Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global Prevalence of Depression and Elevated Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wu, M.; Dong, Y.; Yue, X.; Shang, X.; Sui, M.; Liu, X. A Meta-Analysis of the Detection Rate of Depressive Symptoms among Primary School Students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2020, 34, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hong, Y.; Yang, S. Relationships among Adolesents’ Life Events, Self-Esteem, Depression and Suicide Ideation. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 18, 190–191+164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Zou, Y.; Gu, F.; Meng, J.; Gao, L.; Shen, Y. Influencing Factors of Depressive Symptoms in Zhejiang Adolescents. Prev. Med. 2021, 33, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Universal Health Coverage Collaborators. Measuring Universal Health Coverage Based on An index of Effective Coverage of Health Services in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1250–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy, 4th ed.; Beacon Press: Boston, MI, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tongeren, D.R.; Green, J.D. Combating Meaninglessness: On the Automatic Defense of Meaning. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 1372–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.B.; Salcuni, S.; Delvecchio, E. Meaning in Life, Self-Control and Psychological Distress among Adolescents: A Cross-National Study. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wong, P.T.P.; Li, D. The Effects of Relationship and Self-Concept on Meaning in Life: A Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y. Relationship between Parental Emotional Maltreatment and Inattention-Hyperativity Symptoms in Adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 27, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Fitch-Martin, A.R.; Donnelly, J.; Rickard, K.M. Meaning in Life and Health: Proactive Health Orientation Links Meaning in Life to Health Variables among American Undergraduates. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Ji, L.; Liu, M.; Ye, B. The Relationship between Search for Meaning in Life and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Key Roles of the Presence of Meaning in Life and Life Events among Chinese Adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Yao, X. The Relationship between College Freshmen’s Meaning in Life and Depression: Examining the Interacting and Mediating Effects. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2015, 31, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Netzer, P. Prioritizing Meaning as a Pathway to Meaning in Life and Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 20, 1863–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Motivation, Meaning, and Wellness: A Self-Determination Perspective on the Creation and internalization of Personal Meanings and Life Goals. In The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Wong, P.T.P., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Damon, W.; Menon, J.; Bronk, K.C. The Development of Purpose during Adolescence. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2010, 7, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Jiang, S. Life Meaning and Well-Being in Adolescents. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2013, 27, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Süß, H.M. Measuring Slips and Lapses When They Occur—Ambulatory Assessment in Application to Cognitive Failures. Conscious. Cogn. 2014, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrigan, N.; Barkus, E. A Systematic Review of Cognitive Failures in Daily Life: Healthy Populations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 63, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, T.W.; Schnapp, M.A. The Relationship between Negative Affect and Reported Cognitive Failures. Depress. Res. Treat. 2014, 2014, 396195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelm, O.; Witthöft, M.; Schipolowski, S. Self-reported Cognitive Failures: Competing Measurement Models and Self-Report Correlates. J. Individ. Differ. 2010, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, A.; Dalby, J.; King, M. Cognitive Failures and Stress. Psychol. Rep. 1998, 82, 1432–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z. A Review of research on cognitive failures.C onception Measurement and related research. Psychol. Explor. 2011, 31, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C. The Mediating Effect of Negative Emotions between Mobile Phone Dependence and Cognitive Failures. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 25, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Li, L. Relationship between Mobile Phone Dependence and Cognitive Failure in College Students: A Chain Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Depression. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2018, 32, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Feng, C.; Wang, Y. Parental Psychological Control and Adolescents Depression during the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Mediating and Moderating Effect of Self-Concept Clarity and Mindfulness. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, L.Y.; Seligman, M.E.; Teasdale, J.D. Learned Helplessness in Humans: Critique and Reformulation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1978, 87, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Yu, G. The Association between Boredom Proneness and College Students’ Cognitive Failures: The Moderating and Mediating Role of Effortful Control. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2020, 36, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resource Caravans and Engaged Settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Dong, X. Influence of Core Self-Evaluations on Cognitive Failures: Mediation of Boredom Proneness. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 25, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzelman, S.J.; Trent, J.; King, L.A. Encounters with Objective Coherence and the Experience of Meaning in Life. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markett, S.; Reuter, M.; Sindermann, C.; Montag, C. Cognitive Failure Susceptibility and Personality: Self-Directedness Predicts Everyday Cognitive Failure. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020, 159, 109916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, D.E.; Cooper, P.F.; Fitzgerald, P.; Parkes, K.R. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and Its Correlates. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, S.A.; Masters, K.S.; Park, C.L. A Meaningful Life Is a Healthy Life: A Conceptual Model Linking Meaning and Meaning Salience to Health. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2018, 22, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.D.; Lindsay, E.K. How Does Mindfulness Training Affect Health? A Mindfulness Stress Buffering Account. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, B.; Robins, R.W.; Pande, N. Mediating Role of Self-Esteem on the Relationship between Mindfulness, Anxiety, and Depression. Pers. Individ. 2016, 96, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Liu, X.; Du, J.; Xu, W. The Relationship between Mindfulness and Intimate Relationship Satisfaction: Dynamic Evidence. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 26, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; He, J.; Chen, H. A Meta-Analysis of Effect of Mindfulness Therapy in Patients with Postpartum Depression. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2020, 34, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Zhang, J.; Song, C.; Gao, B.; Yang, Y.; Yu, X. Drug Combined with Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Treatment of Residual Symptoms of Recurrent Depressive Disorder. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2019, 33, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, Z.A.; Soh, K.L.; Mukhtar, F.; Soh, K.Y.; Oladele, T.O.; Soh, K.G. Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy among Depressed Individuals with Disabilities in Nigeria: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 296, 113680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Effectiveness Mindfulness Cognitive Therapy Intervention on Sleep Quality of College Graduates with Depression. Chin. J. School Health 2019, 40, 1345–1347+1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Cao, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, R.; Li, C.; Ru, S.; Tan, Y.; Li, Y. Effect of Resilience in Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Patients with Depression. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2021, 35, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J. Empirical Explorations of Mindfulness: Conceptual and Methodological Conundrums. Emotion 2010, 10, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holas, P.; Jankowski, T. A Cognitive Perspective on Mindfulness. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.; Malinowski, P. Meditation, mindfulness, and cognitive flexibility. Conscious. Cogn. 2009, 18, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, T.; Bak, W. Mindfulness as a Mediator of the Relationship between Trait Anxiety, Attentional Control, and Cognitive Failures. A Multimodal Inference Approach. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2019, 142, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Fang, P.; Wu, D.; Jiang, J.; Liu, B.; Yang, Q.; Xiao, W. Study on the Improvement of Mental Cognitive Function and Learning Efficiency by Mindfulness Training. J. Mod. Med. Health 2020, 36, 1576–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Bott, E.M.; Suh, H. Connecting Mindfulness and Meaning in Life: Exploring the Role of Authenticity. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, B.L.; Abramson, L.Y.; Miller, N.; Haeffel, G. Cognitive Vulnerability-Stress Theories of Depression: Examining Affective Specificity in the Prediction of Depression Versus Anxiety in Three Prospective Studies. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2004, 28, 309–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gan, Y. Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2010, 24, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Fan, C.; Liu, Q.; Lian, S.; Cao, M.; Zhou, Z. The Mediating Role of Boredom Proneness and the Moderating Role of Meaning in Life in the Relationship between Mindfulness and Depressive Symptoms. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4635–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q. Psychometric evaluation of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire in Chinese middle school students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 21, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wei, L.; Lianggue, G.; Guochen, Z.; Chenggue, W. Applicability of the Chinese beck depression inventory. Compr. Psychiatry 1988, 29, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Q.; Xie, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Jia, Q.; Fang, Z. Influencing Factors of Depression Tendency among High School Students: A Nested Case-Control Study. Chin. J. Public. Health 2022, 38, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhu, L.; Yan, T. Validity and Reliability of the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire in Chinese College Students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 24, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Peng, Y.; Luo, X.; Mao, H.; Luo, Y.; Hu, R.; Xiong, S. Mobile Phone Addiction and Cognitive Failures in Chinese Adolescents: The Role of Rumination and Mindfulness. J. Psychol. Afr. 2021, 31, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Peng, Y.; Mao, H.; Zhang, B. Relationship between Adolescents’ Smart Phone Addiction and Interpersonal Adaptation: Mediating Effect of Emotion Regulation Efficacy and Cognitive Failures. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 29, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cui, H.; Zhou, R.; Jia, Y. Revision of Mindful Attention Awareness Scale(MAAS). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 20, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zeng, B.; Chen, P.; Mai, Y.; Teng, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J.; Yang, X.; Zhao, J. Mindfulness and Suicide Risk in Undergraduates: Exploring the Mediating Effect of Alexithymia. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qu, G.; Kong, H.; Ma, X.; Cao, L.; Li, T.; Wang, Y. Rumination and “Hot” Executive Function of Middle School Students during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Moderated Mediation Model of Depression and Mindfulness. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 989904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Duan, X.; Li, M.; Li, Y. The Relationship between Mindfulness and Social Adaptation among Migrant Children in China: The Sequential Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Different Methods for Testing Moderated Mediation Models: Competitors or Backups? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugan, G. Meaning-in-Life in Nursing-Home Patients: A Correlate with Physical and Emotional Symptoms. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 1030–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. The Relationships between Self-Identity and Meaning in Life: The Role of Psychological Capital. Adv. Psychol. 2016, 6, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michl, L.C.; Mclaughlin, K.A.; Shepherd, K.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Rumination as a Mechanism Linking Stressful Life Events to Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Longitudinal Evidence in Early Adolescents and Adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 122, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsaksen, T.; Grimholt, T.K.; Skogstad, L.; Lerdal, A.; Ekeberg, Ø.; Heir, T.; Schou-Bredal, I. Self-Diagnosed Depression in the Norwegian General Population—Associations with Neuroticism, Extraversion, Optimism, and General Self-Efficacy. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D. Middle-School Students’ Meaning in Life: The Characteristics of Its Development and Relationship with Learning Motivation and Academic Achievement. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 35, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.; Helton, W.S. Sustained Attention Failures Are Primarily Due to Sustained Cognitive Load, Not Task Monotony. Acta Psychol. 2014, 153, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary Magic. Resilience Processes in Development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, P.; Lim, H.J. Mindfulness at Work: Positive Affect, Hope, and Optimism Mediate the Relationship between Dispositional Mindfulness, Work Engagement, and Well-Being. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1250–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keye, M.D.; Pidgeon, A.M. Investigation of the Relationship between Resilience, Mindfulness, and Academic Self-Efficacy. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, K.; Li, T.; Lu, L. The Impact of Mindfulness on Subjective Well-Being of College Students: The Mediating Effects of Emotion Regulation and Resilience. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 38, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbilt-Adriance, E.; Shaw, D.S. Conceptualizing and Re-Evaluating Resilience across Levels of Risk, Time, and Domains of Competence. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 11, 30–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Xiao, T.; Liu, H.; Hu, W. The Relationship between Parental Rejection and Internet Addiction in Left-Behind Children: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Age | 13.70 | 1.22 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 Gender | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| 3 Meaning in life | 38.78 | 8.06 | −0.05 | −0.09 ** | 1 | - | - | - |

| 4 Cognitive failures | 68.51 | 16.51 | 0.14 ** | 0.07 * | −0.1 5 ** | 1 | - | - |

| 5 Mindfulness | 54.09 | 12.70 | −0.18 ** | −0.00 | 0.14 ** | −0.64 ** | 1 | - |

| 6 Depression | 10.27 | 7.25 | 0.19 ** | 0.05 | −0.25 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.41 ** | 1 |

| Depression | Cognitive Failures | Depression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | |

| Gender | 0.04 | 1.09 | [−0.03, 0.10] | 0.06 | 1.91 | [−0.00, 0.12] | 0.01 | 0.36 | [−0.05, 0.06] |

| Age | 0.17 | 5.66 *** | [0.11, 0.24] | 0.13 | 4.29 *** | [0.07, 0.19] | 0.11 | 3.85 *** | [0.05, 0.16] |

| Meaning in life | −0.24 | −7.73 *** | [−0.30, −0.18] | −0.14 | −4.42 *** | [−0.20, −0.08] | −0.17 | −6.04 *** | [−0.22, −0.11] |

| Cognitive failures | 0.31 | 8.25 *** | [0.24, 0.39] | ||||||

| Mindfulness | −0.17 | −4.66 *** | [−0.25, −0.10] | ||||||

| Cognitive failures × Mindfulness | −0.05 | −2.26 * | [−0.10, −0.01] | ||||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.28 | ||||||

| F | 33.00 *** | 14.94 *** | 60.65 *** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Kong, H.; Feng, C.; Cao, L.; Li, T.; Wang, Y. The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Depression among Chinese Junior High School Students: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Cognitive Failures and Mindfulness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043041

Li Y, Jin Y, Kong H, Feng C, Cao L, Li T, Wang Y. The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Depression among Chinese Junior High School Students: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Cognitive Failures and Mindfulness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043041

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ying, Yihan Jin, Huiyan Kong, Chao Feng, Lei Cao, Tiantian Li, and Yue Wang. 2023. "The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Depression among Chinese Junior High School Students: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Cognitive Failures and Mindfulness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043041

APA StyleLi, Y., Jin, Y., Kong, H., Feng, C., Cao, L., Li, T., & Wang, Y. (2023). The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Depression among Chinese Junior High School Students: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Cognitive Failures and Mindfulness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043041