Air Pollution, Environmental Protection Tax and Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Subjective Air Pollution and Residents’ Well-Being

2.2. Research on Air Pollution and Environmental Protection Tax

2.3. Research on Environmental Protection Tax and Well-Being

3. Influence Mechanism and Research Hypothesis

3.1. Influence Mechanism Analysis

3.2. Research Hypotheses

4. Research Design

4.1. Data Sources

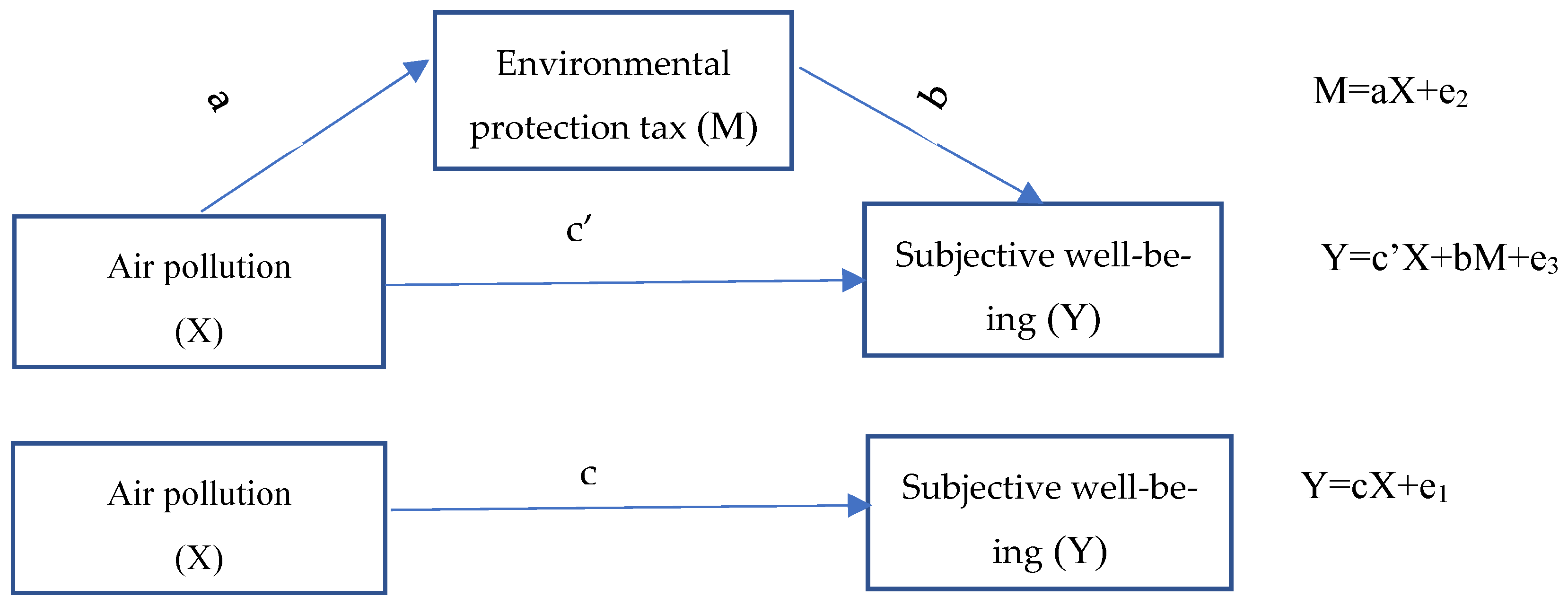

4.2. Empirical Model

4.3. Variable Selection

5. Empirical Test

5.1. Basic Regression Results

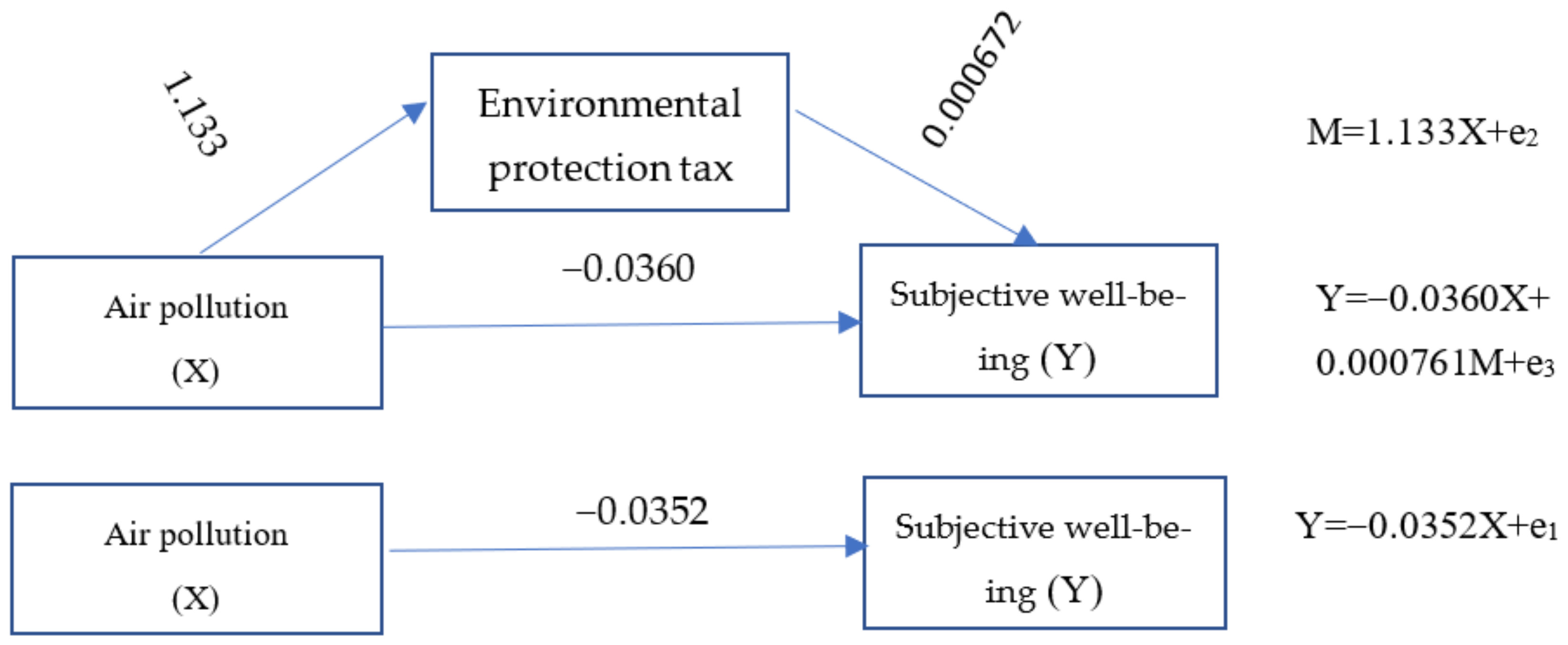

5.2. Mediation Effect Mechanism Test

5.3. Heterogeneity Research

5.3.1. Income Heterogeneity Test

5.3.2. Region Heterogeneity Test

5.3.3. Urban-Rural Heterogeneity Test

5.3.4. Age Heterogeneity Test

5.3.5. Gender Heterogeneity Test

5.4. Robustness Check

5.5. Endogenous Problems

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Recommendations

6.3. Limation and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brunekreef, B.; Holgate, S.T. Air Pollution and Health. Lancet 2002, 360, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, S.; Cirach, M.; Pereira-Barboza, E.; Mueller, N.; Barrera-Gómez, J.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; de Hoogh, K.; Hoek, G.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Premature Mortality Due to Air Pollution in European Cities: A Health Impact Assessment. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e121–e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, E. Impact of Air Pollution Hazards on Human Development. In Health Impacts of Developmental Exposure to Environmental Chemicals; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo, I.H.; Bakola, M.; Stuckler, D. The Impact of Air Pollution on COVID-19 Incidence, Severity, and Mortality: A Systematic Review of Studies in Europe and North America. Environ. Res. 2022, 215, 114155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X. The Impact of Exposure to Air Pollution on Cognitive Performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9193–9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Zhang, S. Willingness to pay for clean air: Evidence from air purifier markets in China. J. Political Econ. 2020, 128, 1627–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, B.; He, Q.; Chen, B.; Wei, J.; Mahmood, R. Dynamic Assessment of PM2.5 Exposure and Health Risk Using Remote Sensing and Geo-Spatial Big Data. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 253, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Shin, K.; Managi, S. Subjective Well-Being and Environmental Quality: The Impact of Air Pollution and Green Coverage in China. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 153, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Happiness in the Air: How Does a Dirty Sky Affect Mental Health and Subjective Well-Being? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 85, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krekel, C.; MacKerron, G. How Environmental Quality Affects Our Happiness; World Happiness Report 2020; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Tax Law of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-12/26/content_5152775.htm (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Bashir, M.F.; Ma, B.; Shahbaz, M.; Shahzad, U.; Vo, X.V. Unveiling the Heterogeneous Impacts of Environmental Taxes on Energy Consumption and Energy Intensity: Empirical Evidence from OECD Countries. Energy 2021, 226, 120366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüss-Üstün, A.; Wolf, J.; Corvalán, C.; Bos, R.; Neira, M. Preventing Disease through Healthy Environments: A Global Assessment of the Burden of Disease from Environmental Risks; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, S.; Akay, A.; Brereton, F.; Cuñado, J.; Martinsson, P.; Moro, M.; Ningal, T.F. Life Satisfaction and Air Quality in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 88, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ren, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, L. The Impact of Air Pollution on Individual Subjective Well-Being: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada, G.; Iturra, V. If the Air Was Cleaner, Would We Be Happier? An Economic Assessment of the Effects of Air Pollution on Individual Subjective Well-Being in Chile. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerron, G.; Mourato, S. Life Satisfaction and Air Quality in London. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, M. Exploring the Effect of Subjective Air Pollution on Happiness in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 43299–43311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Zhang, W. Subjective Air Pollution, Income Level and Residents’ Happiness. Financ. Res. 2020, 46, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Sanduijav, C.; Ferreira, S.; Filipski, M.; Hashida, Y. Air Pollution and Happiness: Evidence from the Coldest Capital in the World. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 187, 107085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D. The Role of Carbon Taxes in Adjusting to Global Warming. Econ. J. 1991, 101, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenberg, A.L. Green Tax Reforms and the Double Dividend: An Updated Reader’s Guide. Int. Tax Public Financ. 1999, 6, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.P.; Chen, B. “Carbon Peak, Carbon Neutrality” Goal and Construction of Green Tax System. Tax Econ. Res. 2022, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilinski, A.; Ruzhytskyi, I.; Patlachuk, V.; Patlachuk, O.; Kaminska, B. Environmental Taxes as a Condition of Business Responsibility in the Conditions of Sustainable Development. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2019, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, S.; Schimmack, U.; Diener, E. Progressive Taxation and the Subjective Well-Being of Nations. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 23, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drus, M. Happy Taxpayers: How Paying Taxes Can Make People Happy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akay, A.; Bargain, O.; Dolls, M.; Neumann, D.; Peichl, A.; Siegloch, S. Happy Taxpayers? Income Taxation and Well-Being. SOEPpaper. 1 December 2012. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/67179 (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Sasmaz, M.; Sakar, E. The Effect of Taxes and Public Expenditures on Happiness: Empirical Evidence from OECD Countries. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2020, 7, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H. Environment and Happiness: Valuation of Air Pollution Using Life Satisfaction Data. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 58, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Su, L. Strategies for Improving Tax Policy to Improve the Well-Being of Chinese Residents. Econ. Res. Ref. 2018, 24, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Wei, W.Q.; Zhou, S. Macro Tax Burden, Public Expenditure Structure and Individual Well-Being: A Discussion on “Government Transformation”. Society 2012, 32, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.P.; Yang, F. Tax Burden, Tax Expression Right and Residents’ Well-Being: An Empirical Study Based on Chinese Prefectural City Data. Tax Res. 2017, 6, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Fan, X. Macroeconomic Tax Burden, Pro-poor Expenditure and Public Well-Being. Contemp. Econ. Res. 2013, 9, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, D.; Boamah, V. Environmental Governance, Green Tax and Happiness—An Empirical Study Based on CSS (2019) Data. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Yin, X. Environmental Regulation, Technological Innovation and Energy Consumption—A Cross-Region Analysis in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, L.H. Environmental Taxation and the Double Dividend: A Reader’s Guide. Int. Tax Public Financ. 1995, 2, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Ya, Q.; Chengfeng, L.; Yuan, Y.; Xiao, C. Nexus between Environmental Tax, Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, and Carbon Dioxide Emissions: Evidence from China, Finland, and Malaysia Based on a Panel-ARDL Approach. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do We Really Know What Makes Us Happy? A Review of the Economic Literature on the Factors Associated with Subjective Well-Being. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, X. The Welfare Effect of “Green water and Green Mountains”: An Empirical Study Based on Residents’ Life Satisfaction. China Econ. Stud. 2019, 4, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Social Survey (CSS) First Open the 2019 Survey Data to the Society. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzI3NDkyMzY4MQ==&mid=2247485308&idx=1&sn=2c90ee6bbae0b0335f65075b3731a9e3&source=41#wechat_redirect (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Levinson, A. Valuing Public Goods Using Happiness Data: The Case of Air Quality. J. Public Econ. 2012, 96, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, R. Government Spending and Happiness of the Population: Additional Evidence from Large Cross-Country Samples. Public Choice 2009, 138, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zeng, S.; Cao, C.; Ma, H.; Sun, D. Impacts of Pollution Abatement Projects on Happiness: An Exploratory Study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A.; Frijters, P. How Important Is Methodology for the Estimates of the Determinants of Happiness? Econ. J. 2004, 114, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Environmental Pollution, Government Regulation and Residents’ Happiness—An Empirical Analysis Based on CGSS(2008) Data. Contemp. Econ. Sci. 2015, 37, 59–68, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, S.; Wu, F.; Wang, S. Collaborative Innovation in Science and Technology to Help Win the Battle for Blue Sky. Environ. Prot. 2021, 49, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewberl, A. Constructing Instruments for Regressions with Measurement Error When No Additional Data Are Available, with an Application to Patents and R&D. J. Econom. Soc. 1997, 65, 1201–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Wright, J.H.; Yogo, M. A Survey of Weak Instruments and Weak Identification in Generalized Method of Moments. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2002, 20, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWB | 1 = very unhappy; 2 = not very happy; 3 = relatively happy; 4 = very happy | 3.17 | 0.8 | 1 | 4 |

| airpol | 1 = not serious; 2 = not very serious; 3 = relatively serious; 4 = very serious | 2.06 | 0.93 | 1 | 4 |

| envt | 0.73–166.87 | 64.39 | 43.3 | 0.73 | 166.87 |

| edu | 1 = junior high school and below; 2 = high school; 3 = undergraduate; 4 = graduate and above | 1.57 | 0.81 | 1 | 4 |

| lninc | 0–14.22 | 8.52 | 3.43 | 0 | 14.22 |

| gender | 0 = female; 1 = male | 0.43 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| age | 18–69 years | 46.21 | 14.21 | 18 | 69 |

| age2 | 324–4761 years | 2337.38 | 1274.74 | 324 | 4761 |

| marr | 0 = not married; 1 = married | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 |

| minzu | 0 = Minority; 1 = Han | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 |

| hukou | 0 = urban; 1 = rural | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 |

| work | 0 = non-working state; 1 = working state | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| dzx | 1 = east; 2 = central; 3 = west | 1.86 | 0.81 | 1 | 3 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | SWB | Envt | SWB |

| airpol | −0.0352 *** | 1.133 * | −0.0360 *** |

| (0.0124) | (0.657) | (0.0124) | |

| envt | 0.000672 ** | ||

| (0.000272) | |||

| lninc | 0.00824 ** | −0.130 | 0.00833 ** |

| (0.00376) | (0.199) | (0.00375) | |

| edu | 0.0453 ** | 2.742 *** | 0.0434 ** |

| (0.0184) | (0.975) | (0.0184) | |

| gender | −0.0207 | −3.061 ** | −0.0186 |

| (0.0240) | (1.268) | (0.0240) | |

| age | −0.0474 *** | −0.496 | −0.0470 *** |

| (0.00649) | (0.343) | (0.00649) | |

| age2 | 0.000520 *** | 0.00543 | 0.000517 *** |

| (7.00 × 10−5) | (0.00370) | (6.99 × 10−5) | |

| marr | 0.282 *** | 4.161 ** | 0.279 *** |

| (0.0347) | (1.836) | (0.0347) | |

| minzu | 0.0430 | 31.08 *** | 0.0221 |

| (0.0438) | (2.319) | (0.0446) | |

| hukou | 0.000745 | 11.69 *** | −0.00711 |

| (0.0287) | (1.520) | (0.0289) | |

| work | −0.0415 | 1.760 | −0.0427 |

| (0.0283) | (1.499) | (0.0283) | |

| dzx | −0.0189 | −4.092 *** | −0.0162 |

| (0.0146) | (0.773) | (0.0147) | |

| Constant | 3.879 *** | 36.86 *** | 3.854 *** |

| (0.158) | (8.375) | (0.159) | |

| Observations | 4.837 | 4.837 | 4.837 |

| R-squared | 0.025 | 0.067 | 0.026 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| High-Income | Low-Income | |

| airpol | −0.0226 | −0.0402 *** |

| (0.0204) | (0.0156) | |

| Observations | 1.600 | 3.237 |

| R-squared | 0.028 | 0.027 |

| F | 4.14 | 8.23 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Eastern | Central and Western |

| airpol | −0.0237 | −0.0570 ** |

| (0.0188) | (0.0222) | |

| Observations | 1.993 | 1.536 |

| R-squared | 0.029 | 0.028 |

| F | 6.00 | 4.45 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | |

| airpol | −0.0202 | −0.0413 *** |

| (0.0216) | (0.0151) | |

| Observations | 1.492 | 3.345 |

| R-squared | 0.029 | 0.025 |

| F | 4.36 | 8.67 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Elderly | Young | |

| airpol | −0.0318 | −0.0372 ** |

| (0.0226) | (0.0149) | |

| Observations | 1.468 | 3.369 |

| R-squared | 0.024 | 0.028 |

| F | 3.28 | 8.64 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |

| airpol | −0.0187 | −0.0592 *** |

| (0.0163) | (0.0193) | |

| Constant | 3.857 *** | 3.876 *** |

| Observations | 2.746 | 2.091 |

| R-squared | 0.023 | 0.032 |

| F | 6.53 | 6.97 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satis | Envt | Satis | |

| airpol | −0.217 *** | 1.169 * | −0.223 *** |

| (0.0338) | (0.657) | (0.0337) | |

| envt | 0.00433 *** | ||

| (0.000740) | |||

| lninc | 0.0412 *** | −0.121 | 0.0417 *** |

| (0.0102) | (0.199) | (0.0102) | |

| edu | 0.289 *** | 2.704 *** | 0.277 *** |

| (0.0502) | (0.977) | (0.0501) | |

| gender | −0.0931 | −3.077 ** | −0.0798 |

| (0.0654) | (1.271) | (0.0652) | |

| age | −0.141 *** | −0.505 | −0.139 *** |

| (0.0177) | (0.344) | (0.0176) | |

| age2 | 0.00158 *** | 0.00548 | 0.00156 *** |

| (0.000191) | (0.00371) | (0.000190) | |

| marr | 0.488 *** | 4.354 ** | 0.469 *** |

| (0.0949) | (1.847) | (0.0947) | |

| minzu | 0.0313 | 30.90 *** | −0.102 |

| (0.120) | (2.325) | (0.121) | |

| hukou | −0.147 * | 11.60 *** | −0.197 ** |

| (0.0783) | (1.524) | (0.0785) | |

| work | −0.0383 | 1.701 | −0.0456 |

| (0.0772) | (1.502) | (0.0770) | |

| dzx | −0.129 *** | −4.070 *** | −0.112 *** |

| (0.0398) | (0.775) | (0.0398) | |

| Constant | 9.627 *** | 37.05 *** | 9.466 *** |

| (0.431) | (8.384) | (0.430) | |

| Observations | 4.804 | 4.804 | 4.804 |

| R-squared | 0.047 | 0.067 | 0.054 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWB | Envt | SWB | |

| airpol | −0.0470 *** (0.0174) | 0.0303 * (0.0158) | −0.0482 *** (0.0174) |

| envt | 0.000928 ** | ||

| (0.000384) | |||

| (0.00526) | (0.00479) | (0.00526) | |

| edu | 0.0432 * | 0.0659 *** | 0.0406 |

| (0.0259) | (0.0235) | (0.0259) | |

| gender | −0.0288 | −0.0712 ** | −0.0260 |

| (0.0336) | (0.0305) | (0.0337) | |

| age | −0.0649 *** | −0.0134 | −0.0645 *** |

| (0.00917) | (0.00827) | (0.00917) | |

| age2 | 0.000722 *** | 0.000152 * | 0.000718 *** |

| (9.90 × 10−5) | (8.91 × 10−5) | (9.90 × 10−5) | |

| marr | 0.362 *** | 0.102 ** | 0.358 *** |

| (0.0484) | (0.0442) | (0.0484) | |

| minzu | 0.0393 | 0.865 *** | 0.0108 |

| (0.0614) | (0.0565) | (0.0625) | |

| hukou | 0.0103 | 0.291 *** | −0.000771 |

| (0.0404) | (0.0367) | (0.0406) | |

| work | −0.0563 | 0.0704 * | −0.0580 |

| (0.0399) | (0.0361) | (0.0399) | |

| dzx | −0.0225 | −0.133 *** | −0.0188 |

| (0.0205) | (0.0188) | (0.0206) | |

| Observations | 4.837 | 4.837 | 4.837 |

| R-squared | 0.047 | 0.067 | 0.054 |

| Variables | First Stage | Second Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Airpol | SWB | |

| Airpolgap3 | 0.3289045 *** | |

| (0.0029) | ||

| Airpol | −0.0252 * | |

| (0.0146) | ||

| Constant | (0.09512) | (0.159) |

| Observations | 4.804 | 4.804 |

| R2 | 0.7322 | 0.0251 |

| F | 12773.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Tang, D. Air Pollution, Environmental Protection Tax and Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032599

Wang J, Tang D. Air Pollution, Environmental Protection Tax and Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032599

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jingjing, and Decai Tang. 2023. "Air Pollution, Environmental Protection Tax and Well-Being" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032599

APA StyleWang, J., & Tang, D. (2023). Air Pollution, Environmental Protection Tax and Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032599