The Impact of Migration Experience on Rural Residents’ Mental Health: Evidence from Rural China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Measure of Mental Health

2.2. Rural Residents’ Mental Health

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures of Mental Health

3.3. Measures of Migration Experience

3.4. Other Covariates and Descriptive Statistics

3.5. Empirical Strategies

3.5.1. Baseline Model

3.5.2. Intermediate Effect Test

4. Results

4.1. Effects of Migration Experience on Rural Residents’ Mental Health

4.2. Robustness Checks

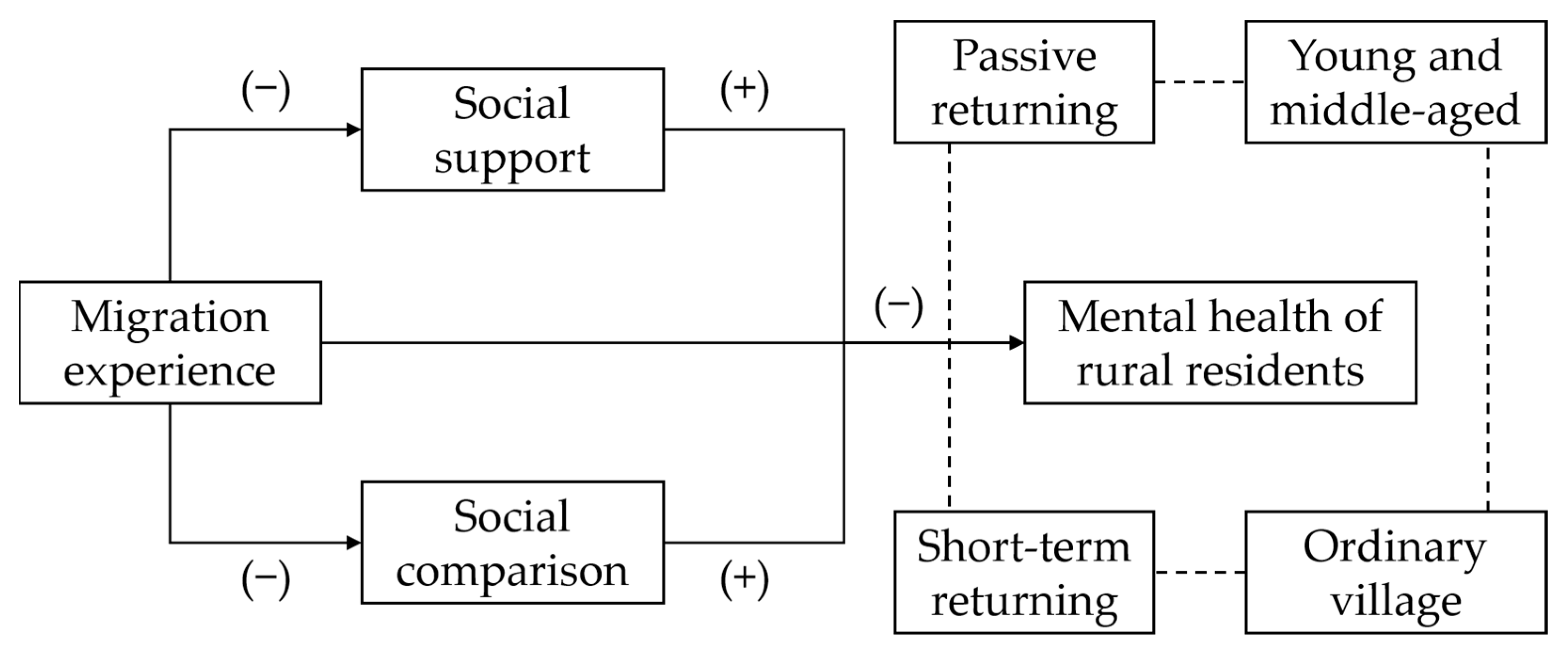

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

4.4. Heterogeneous Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category (%) | Mean | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 = Almost None | 1 = Rare | 2 = Often | 3 = All the Time | ||

| I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me. | 55.88 | 32.54 | 8.31 | 3.27 | 1.59 |

| I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor. | 56.48 | 31.41 | 9.47 | 2.63 | 1.58 |

| I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family or friends. | 69.31 | 24.02 | 5.20 | 1.48 | 1.39 |

| I felt I was just as good as other people. | 65.94 | 24.96 | 6.64 | 2.46 | 1.46 |

| I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing. | 66.82 | 26.10 | 5.52 | 1.57 | 1.42 |

| I felt depressed. | 59.08 | 32.52 | 6.77 | 1.64 | 1.51 |

| I felt it hard to do anything. | 62.67 | 25.99 | 8.27 | 3.07 | 1.52 |

| I felt hopeless about the future. | 73.30 | 19.64 | 4.66 | 2.40 | 1.36 |

| I thought my life had been a failure. | 74.81 | 19.02 | 4.21 | 1.95 | 1.33 |

| I felt fearful. | 78.07 | 17.72 | 3.26 | 0.95 | 1.27 |

| My sleep was restless. | 54.89 | 26.69 | 13.40 | 5.02 | 1.69 |

| I was unhappy. | 59.86 | 31.50 | 6.88 | 1.76 | 1.51 |

| I talked less than usual. | 68.07 | 25.53 | 4.92 | 1.48 | 1.40 |

| I felt lonely. | 73.26 | 20.00 | 4.85 | 1.89 | 1.35 |

| People were unfriendly. | 77.59 | 18.38 | 3.11 | 0.92 | 1.27 |

| I didn’t enjoy life. | 78.50 | 16.82 | 3.48 | 1.21 | 1.27 |

| I had crying spells. | 80.72 | 15.96 | 2.54 | 0.78 | 1.23 |

| I felt sad. | 66.79 | 25.20 | 5.99 | 2.02 | 1.43 |

| I felt that people disliked me. | 80.59 | 15.97 | 2.61 | 0.83 | 1.24 |

| I could not get going. | 83.57 | 13.26 | 2.39 | 0.78 | 1.20 |

References

- Su, Y.; Tesfazion, P.; Zhao, Z. Where are the migrants from? Inter- vs. intra-provincial rural-urban migration in China. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 47, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Rockett, I.R.H.; Zhu, W.; Ellison-Barnes, A. Mental Health Status and Related Characteristics of Chinese Male Rural–Urban Migrant Workers. Community Ment. Health J. 2012, 48, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.Y.; Zheng, Y.F.; Qian, W.R. Behavior analysis of migrant workers’ integration into cities-Based on the survey data of 1632 migrant workers. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2016, 1, 26–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qin, L.J.; Cheng, J.; Pan, J. Effects of health on labor supply time of migrant workers. Stat. Inf. Forum 2015, 3, 103–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, C.; Saka, M.; Bone, L.; Jacobs, R. The Role of Mental Health on Workplace Productivity: A Critical Review of the Literature. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangaramoorthy, T.; Carney, M.A. Immigration, Mental Health and Psychosocial Well-being. Med. Anthropol. 2021, 40, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frijters, P.; Johnston, D.W.; Shields, M.A. Mental health and labor market participation: Evidence from IV panel data models. IZA Discuss. Pap. 2010, 4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.; Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.; Wittchen, H.U.; Jonsson, B. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur. J Neurol. 2012, 19, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hou, B.; Li, S. The influence of living pressure and living conditions on the mental health of migrant workers. Urban Probl. 2017, 9, 94–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liang, H.X. The applicability of “healthy migration”, the significance of generation differences and the mediation of labor rights and interests. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2020, 6, 49–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Stanton, B.; Fang, X.; Xiong, Q.; Yu, S.; Lin, D.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, B. Mental Health Symptoms among Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China: A Comparison with Their Urban and Rural Counterparts. World Health Popul. 2009, 11, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoi, C.K.; Chen, W.; Zhou, F.; Sou, K.; Hall, B.J. The Association Between Social Resources and Depressive Symptoms Among Chinese Migrants and Non-Migrants Living in Guangzhou, China. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2015, 9, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.H.; Lv, G.M. Study on the subjective welfare effect of population mobility in the process of urbanization. Sta. Res. 2020, 10, 115–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.Y.; Qian, W.R. The influence of migrant workers’ out-migration for work on marriage relationship-Based on the quantitative analysis of 904 migrant workers in Zhejiang Province. Popul. Northwest 2013, 2, 60–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Rose, N. Urban social exclusion and mental health of China’s rural-urban migrants–A review and call for research. Health Place 2017, 48, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.S.; Li, J. A study on the employment mobility of migrant workers. Manag. World 2008, 7, 70–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.Y. Returning Migrant Workers: A Life Course Perspective; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.N. Migrant workers, new demographic dividend and human capital revolution. Reform 2018, 6, 5–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Shi, W. Influencing factors and return effect of rural migrant workers’ return migration. Popul. Res. 2017, 41, 71–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.; Gunatilaka, R. Great Expectations? The Subjective Well-being of Rural–Urban Migrants in China. World Dev. 2010, 38, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Household migration, social support, and psychosocial health: The perspective from migrant-sending areas. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.K.; Johnston, J.M. Depression and health-seeking behaviour among migrant workers in Shenzhen. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 61, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.S.; Huang, F.Q.; Zeng, S.Z. Urban and rural migration and mental health: An empirical study based on Shanghai. Sociol. Res. 2010, 1, 111–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.L.; Hou, J.W.; Zhang, M.; Xin, Z.Q.; Zhang, H.C.; Sun, L.; Dou, D.H. A Cross-cutting historical study on the changes of the mental health level of Migrant Workers in China: 1995–2011. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2015, 4, 466–477. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H. Mental health status of migrant workers from the perspective of intergenerational differences. Popul. Res. 2014, 4, 87–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nie, W.; Feng, X.T. Urban integration and mental health of migrant workers: An empirical survey of migrant workers in the Pearl River Delta. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 5, 32–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, X.H.; Liu, Y.; Song, P.; Han, H.Y.; Pan, Y.Y.; Sun, Q.M. Event-related potentials of cognitive impairment in patients with mild to moderate depression. J. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 3, 38–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.L.; Song, Y.P.; Li, J.T. Study on the stroop effect task of emotional event-related potential in patients with coronary heart disease and depression. Chin. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 23, 2757–2762. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, R.E.; Vernon, S.W. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Its use in a community sample. Am. J. Psychiatry 1983, 140, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boey, K.W. Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1999, 14, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, X.; Stanton, B.; Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Fang, X.; Lin, D.; Mao, R. HIV-related risk factors associated with commercial sex among female migrants in China. Health Care Women Int. 2005, 26, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice (Summary Report); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9241562943 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- He, G.; Xie, J.-F.; Zhou, J.-D.; Zhong, Z.-Q.; Qin, C.-X.; Ding, S.-Q. Depression in left-behind elderly in rural China: Prevalence and associated factors. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 16, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.; Xu, X.Y. Rural “poverty-disease” vicious cycle and the construction of chain health security system in precision poverty alleviation. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2017, 1, 1–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.C.; Wang, H. Study on health related quality of life of rural residents in western. China. Chin. Health Econ. 2005, 24, 8–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Wang, S.; Hsieh, C.-R. The prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among adults in China: Estimation based on a National Household Survey. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 51, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.L. The impact of population mobility on health disparities between urban and rural residents in China. Soc. Sci. China 2013, 2, 46–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, N.W. Rural-to-urban migrant adolescents in Guangzhou, China: Psychological health, victimization, and local and trans-local ties. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 93, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Chang, E.-S.; Wong, E.; Simon, M. The Perceptions, Social Determinants, and Negative Health Outcomes Associated with Depressive Symptoms Among U.S. Chinese Older Adults. Gerontol. 2011, 52, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Sun, X.; Strauss, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, Y. Depressive symptoms and SES among the mid-aged and elderly in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study national baseline. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 120, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.Q.; Niu, J.L.; Mason, W.; Treiman, D. China’s internal migration and health selection effect. Popul. Res. 2012, 36, 102–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Kennedy, B.P.; Glass, R. Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlindsson, T.; Bjarnason, T. Modeling Durkheim on the Micro Level: A Study of Youth Suicidality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1998, 63, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuval, J.T. Migration and stress. In Handbook of Stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects; Goldberger, L., Breznitz, S., Eds.; Free Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. Internal migration, international migration, and physical growth of left-behind children: A study of two settings. Health Place 2015, 36, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennelly, K. Health and Well-Being of Immigrants: The Healthy Migrant Phenomenon. In Immigrant Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.S.; Wang, H.Y. Social support or social comparison: The effect of social network on the mental health of migrant workers. Sociol. Rev. 2022, 5, 126–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Landry, P.F. Migration, environmental hazards, and health outcomes in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 80, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.F.; Zhang, G.W. Subjective well-being of returning migrant workers under the background of rural revitalization: The potential impact of migrant work experience. Northwest Popul. 2022, 9, 1–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Démurger, S.; Xu, H. Return Migrants: The Rise of New Entrepreneurs in Rural China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.B.; He, K.; Zhang, J.B. Does the one-child policy encourage rural workers to go out for work? China Rural. Econ. 2022, 9, 82–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.G.; Lu, M. Migrant health: China’s achievement or its regret? Econ. J. 2016, 3, 79–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.J.; Liang, J.; Lai, D. Study on the happiness of returning migrant workers: The potential impact of migrant work experience. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 45, 20–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lei, W. Religious belief, economic income and subjective well-being of urban and rural residents. Agric. Tech. Econ. 2016, 7, 98–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Social Theory and Social Structure; Simon and Schuster: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Sun, W. Health consequences of rural-to-urban migration: Evidence from panel data in China. Health Econ. 2016, 25, 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.L.Z.; Zhang, S.L. Social adjustment of returning migrant workers from the perspective of lifelong development. Contemp. Youth Res. 2016, 3, 44–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Cook, S.; Salazar, M.A. Internal migration and health in China. Lancet 2008, 372, 1717–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health (the sum of the 20 items) | 8.025 | 9.452 | 0.000 | 60.000 |

| Migration experience (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) | 0.213 | 0.410 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Mutual assistance (five-point Likert scale) | 3.702 | 0.909 | 1.000 | 5.000 |

| Trust in neighbors (five-point Likert scale) | 3.909 | 0.774 | 1.000 | 5.000 |

| Comparison with relatives (five-point Likert scale) | 2.686 | 0.746 | 1.000 | 5.000 |

| Comparison with neighbors (five-point Likert scale) | 2.763 | 0.655 | 1.000 | 5.000 |

| Gender (1 = male; 0 = female) | 0.517 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 50.689 | 12.553 | 18.000 | 87.000 |

| Education level (never went to school = 0, primary school = 1, junior high school = 2, senior high school/technical school/technical secondary school = 3, college and above = 4) | 1.515 | 0.985 | 0.000 | 4.000 |

| Married (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) | 0.898 | 0.303 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Religious belief (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) | 0.108 | 0.310 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Insurance status (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) | 0.942 | 0.233 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Exercise habit (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) | 0.224 | 0.417 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Household income (logged annual house income) | 9.968 | 2.077 | 0.000 | 13.122 |

| Number of brothers and sisters | 3.526 | 1.991 | 0.000 | 8.000 |

| MH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| ME | 0.121 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.127 *** | 0.122 *** |

| (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.030) | |

| Gender | −0.208 *** | −0.167 *** | −0.171 *** | −0.170 *** |

| (0.021) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | |

| Age | 0.020 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.018 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| Age-squared | −0.000 ** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Education | −0.123 *** | −0.115 *** | −0.100 *** | |

| (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.015) | ||

| Married | −0.199 *** | −0.200 *** | −0.177 *** | |

| (0.044) | (0.044) | (0.044) | ||

| Religious belief | 0.051 | 0.045 | 0.038 | |

| (0.044) | (0.044) | (0.044) | ||

| Insurance status | −0.005 | 0.007 | ||

| (0.056) | (0.056) | |||

| Exercise habit | −0.103 *** | −0.088 *** | ||

| (0.030) | (0.030) | |||

| Household income | −0.050 *** | |||

| (0.006) | ||||

| Number of brothers and sisters | 0.021 *** | |||

| (0.007) | ||||

| Observations | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 |

| MH (a) | MH (b) | Happiness | Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| ME | 0.124 *** | 0.211 *** | −0.090 *** | −0.124 *** |

| (0.047) | (0.038) | (0.032) | (0.032) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 |

| Coefficient | ATT | Standard Error | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: adjust for village-level clustering | |||

| 0.122 *** | 0.042 | 7790 | |

| Panel B: ologit estimates | |||

| 0.212 *** | 0.050 | 7790 | |

| Panel C: IV-oprobit estimates | |||

| 0.795 *** | 0.064 | 7790 | |

| Panel D: Heckman two-step methods | |||

| 0.100 *** | 0.030 | 7790 | |

| Panel E: use the PSM to estimate the ATT | |||

| 0.676 * | 0.355 | 7790 | |

| Comparison with Relatives | MH | Comparison with Neighbors | MH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| ME | −0.148 *** | 0.096 *** | −0.106 *** | 0.104 *** |

| (0.032) | (0.030) | (0.033) | (0.030) | |

| Comparison with relatives | −0.294 *** | |||

| (0.018) | ||||

| Comparison with neighbors | −0.330 *** | |||

| (0.020) | ||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 |

| Mutual Assistance | MH | Trust in Neighbors | MH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| ME | −0.145 *** | 0.108 *** | −0.174 *** | 0.102 *** |

| (0.032) | (0.030) | (0.033) | (0.030) | |

| Mutual assistance | −0.110 *** | |||

| (0.014) | ||||

| Trust in neighbors | −0.159 *** | |||

| (0.017) | ||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 |

| MH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Long-term returning | 0.086 *** | 0.102 *** | ||||

| (0.031) | (0.032) | |||||

| Short-term returning | 0.169 *** | 0.195 *** | ||||

| (0.054) | (0.055) | |||||

| Voluntary returning | −0.003 | 0.011 | ||||

| (0.038) | (0.038) | |||||

| Passive returning | 0.209 *** | 0.210 *** | ||||

| (0.047) | (0.048) | |||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 | 7790 |

| Age | Village Appearance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Aged (1) | Young and Middle-Aged (2) | Good (3) | Ordinary (4) | |

| ME | 0.054 | 0.146 *** | 0.054 | 0.135 *** |

| (0.057) | (0.035) | (0.065) | (0.034) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 2867 | 4923 | 2028 | 5762 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, L.; Hou, X.; Lu, H.; Li, X. The Impact of Migration Experience on Rural Residents’ Mental Health: Evidence from Rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032213

Deng L, Hou X, Lu H, Li X. The Impact of Migration Experience on Rural Residents’ Mental Health: Evidence from Rural China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032213

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Li, Xiaohua Hou, Haiyang Lu, and Xuefeng Li. 2023. "The Impact of Migration Experience on Rural Residents’ Mental Health: Evidence from Rural China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032213

APA StyleDeng, L., Hou, X., Lu, H., & Li, X. (2023). The Impact of Migration Experience on Rural Residents’ Mental Health: Evidence from Rural China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032213