Herpes Zoster Risk in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Its Association with Medications Used

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

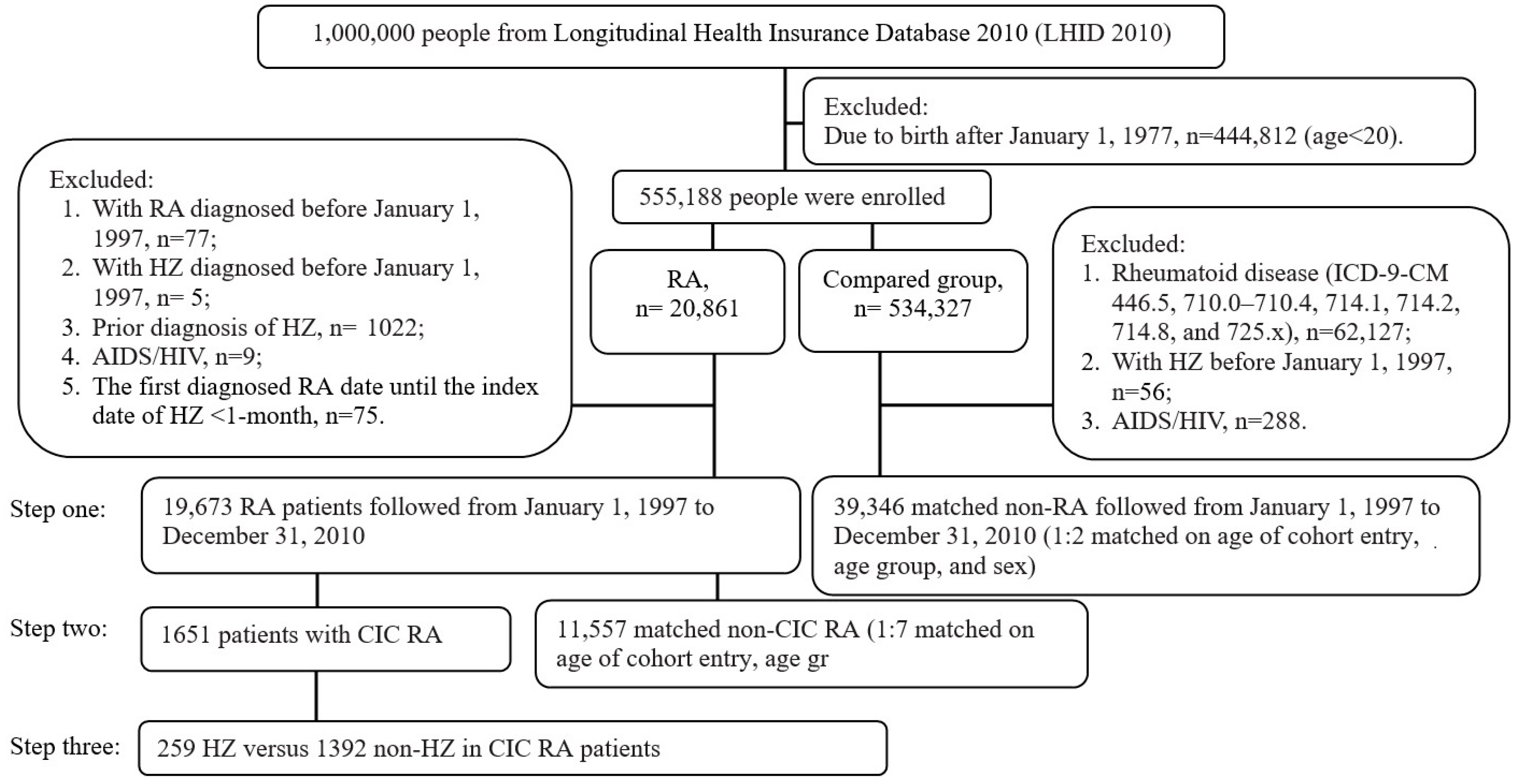

2.1. Source of Data and Study Population

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Ascertainment of RA and CIC RA

2.4. Medications Used in RA

2.5. HZ Outcomes Assessment

2.6. Comorbidities

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dayan, R.R.; Peleg, R. Herpes zoster—Typical and atypical presentations. Postgrad. Med. 2017, 129, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freer, G.; Pistello, M. Varicella-zoster virus infection: Natural history, clinical manifestations, immunity and current and future vaccination strategies. New Microbiol. 2018, 41, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchington, P.R.; Leger, A.J.; Guedon, J.M.; Hendricks, R.L. Herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, the house guests who never leave. Herpesviridae 2012, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.I. Clinical practice: Herpes zoster. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxman, M.; Levin, M.; Johnson, G.; Schmader, K.; Straus, S.; Gelb, L.; Arbeit, R.; Simberkoff, M.; Gershon, A.; Davis, L.; et al. A Vaccine to Prevent Herpes Zoster and Postherpetic Neuralgia in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 2271–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvin, A. Aging, immunity, and the varicella-zoster virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 2266–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.L.; Hall, A.J. What does epidemiology tell us about risk factors for herpes zoster? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Yawn, B.P. Risk Factors for Herpes Zoster: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1806–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klareskog, L.; Catrina, A.I.; Paget, S. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2009, 373, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-F.; Wang, L.-Y.; Chiang, J.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Shen, Y.-C. Assessing whether the association between rheumatoid arthritis and schizophrenia is bidirectional: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, I.B.; Schett, G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2205–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.L.; Wolfe, F.; Huizinga, T.W. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2010, 376, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, L.; Jewell, T.; Laversuch, C.; Samanta, A. A systematic review of the influence of anti-TNF on infection rates in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rev. Bras. De Reum. 2013, 53, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, W.G.; Hyrich, K.L.; Watson, K.D.; Lunt, M.; Galloway, J.; Ustianowski, A.; Symmons, D.P.M.; B S R B R Control Centre Consortium. Drug-specific risk of tuberculosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF therapy: Results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 69, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winthrop, K.L.; Baddley, J.W.; Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Grijalva, C.; Delzell, E.; Beukelman, T.; Patkar, N.M.; Xie, F.; Saag, K.G.; et al. Association Between the Initiation of Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy and the Risk of Herpes Zoster. JAMA 2013, 309, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strangfeld, A.; Listing, J.; Herzer, P.; Liebhaber, A.; Rockwitz, K.; Richter, C.; Zink, A. Risk of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF-alpha agents. JAMA 2009, 301, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veetil, B.M.A.; Myasoedova, E.; Matteson, E.L.; Gabriel, S.E.; Green, A.B.; Crowson, C.S. Incidence and Time Trends of Herpes Zoster in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 65, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitten, A.L.; Choi, H.K.; Hochberg, M.C.; Suissa, S.; Simon, T.A.; Testa, M.A.; Chan, K.A. The risk of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the United States and the United Kingdom. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.B.; Tanaka, Y.; Mariette, X.; Curtis, J.R.; Lee, E.B.; Nash, P.; Winthrop, K.L.; Charles-Schoeman, C.; Thirunavukkarasu, K.; Demasi, R.; et al. Long-term safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis up to 8.5 years: Integrated analysis of data from the global clinical trials. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Tofacitinib: A Review in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Drugs 2017, 77, 1987–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winthrop, K.L.; Curtis, J.R.; Lindsey, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Yamaoka, K.; Valdez, H.; Hirose, T.; Nduaka, C.I.; Wang, L.; Mendelsohn, A.M. Herpes Zoster and Tofacitinib: Clinical Outcomes and the Risk of Concomitant Therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 1960–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, D.A.; Hooper, M.M.; Kremer, J.M.; Reed, G.; Shan, Y.; Wenkert, D.; Greenberg, J.D.; Curtis, J.R. Herpes Zoster Reactivation in Patients with Rheu-matoid Arthritis: Analysis of Disease Characteristics and Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs. Arthritis Care Res. 2015, 67, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Lee, J.; Lee, M.; Choi, W.S.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, M.S.; Hashemi, M.; Rampakakis, E.; Kawai, K.; White, R. Burden of illness, quality of life, and healthcare utilization among patients with herpes zoster in South Korea: A prospective clinical-epidemiological study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeksema, L.; Los, L.I. Vision-Related Quality of Life in Herpetic Anterior Uveitis Patients. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, Z.S.; Hu, Q.Q.; Qin, W.; Liang, L.L.; Cui, F.; Wang, Y.; Pan, F.; Liu, X.L.; Tang, L.; et al. Quality of life and risk factors in patients with herpes zoster. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2022, 102, 3395–3400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gater, A.; Abetz-Webb, L.; Carroll, S.; Mannan, A.; Serpell, M.; Johnson, R. Burden of herpes zoster in the UK: Findings from the zoster quality of life (ZQOL) study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhong, L.Z.; Li, T.T.; Jia, Q.Y.; Li, H.M. Study of risk factors of postherpetic neuralgia. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2022, 102, 3181–3185. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, A.; Urano, W.; Inoue, E.; Taniguchi, A.; Momohara, S.; Yamanaka, H. Incidence of herpes zoster in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis from 2005 to 2010. Mod. Rheumatol. 2015, 25, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, S.; Sakai, R.; Hirano, F.; Miyasaka, N.; Harigai, M. Association Between Medications and Herpes Zoster in Japanese Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A 5-year Prospective Cohort Study. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 44, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.-L.; Chen, Y.-M.; Liu, H.-J.; Chen, D.-Y. Risk and severity of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving different immunosuppressive medications: A case–control study in Asia. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, R.; Tanaka, E.; Nakajima, A.; Inoue, E.; Abe, M.; Sugano, E.; Sugitani, N.; Saka, K.; Ochiai, M.; Higuchi, Y.; et al. Risk of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the biologics era from 2011 to 2015 and its association with methotrexate, biologics, and corticosteroids. Mod. Rheumatol. 2021, 32, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepriano, A.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Bergstra, S.A.; Smolen, J.S.; van der Heijde, D.; Caporali, R.; Edwards, C.J.; Verschueren, P.; de Souza, S.; Pope, J.; et al. Safety of synthetic and biological DMARDs: A systematic literature review informing the 2022 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.C.; Liu, K.C.; Lai, N.S.; Koo, M. Higher incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis or os-teoarthritis-related surgery: A nationwide, population-based, case-control study in Taiwan. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Sundararajan, V.; Halfon, P.; Fong, A.; Burnand, B.; Luthi, J.-C.; Saunders, L.D.; Beck, C.A.; Feasby, T.E.; Ghali, W.A. Coding Algorithms for Defining Comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 Administrative Data. Med Care 2005, 43, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.R.; Zeringue, A.L.; Caplan, L.; Ranganathan, P.; Xian, H.; Burroughs, T.E.; Fraser, V.J.; Cunningham, F.; Eisen, S.A. Herpes zoster risk factors in a national cohort of veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.-H.; See, L.-C.; Kuo, C.-F.; Chou, I.-J.; Chou, M.-J. Prevalence and incidence in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases: A nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 65, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.D.; Reed, G.; Kremer, J.M.; A Tindall, E.; Kavanaugh, A.; Zheng, C.; Bishai, W.R.; Hochberg, M.C. Association of methotrexate and tumour necrosis factor antagonists with risk of infectious outcomes including opportunistic infections in the CORRONA registry. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 69, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; Lukas, C.; Morel, J.; Combe, B. Risk of herpes/herpes zoster during anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint. Bone Spine 2013, 81, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, H.; Moreland, L.; Peterson, H.; Aggarwal, R. Improvement in Herpes Zoster Vaccination in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Quality Improvement Project. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 44, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winthrop, K.L.; Tanaka, Y.; Lee, E.B.; Wollenhaupt, J.; Al Enizi, A.; Azevedo, V.F.; Curtis, J.R. Prevention and management of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: A clinical review. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 40, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Guo, W.; Li, X.; Su, X.; Wan, H.; Sun, Y.; Lin, N. Anti-angiogenic effect of triptolide in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting an-giogenic cascade. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step One | Step Two | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | Matched Non-RA | RA | ||||||

| p Value | CIC | Non-CIC | p Value | 1:7 Matched Non-CIC | p Value | |||

| N | 19,673 | 39,346 | 1651 | 18,022 | 11,557 | |||

| Follow-up for HZ, median (IQR), years | 4.1 (1.9–6.7) | 9.1 (6.1–11.7) | <0.0001 | 3.9 (1.9–6.9) | 4.2 (1.9–6.7) | 0.9336 | 4.1 (1.9–6.7) | 0.9070 |

| Age of cohort entry mean (SD), years | 46.2 (13.6) | 46.0 (13.6) | 0.0855 | 46.2 (12.9) | 46.2 (13.6) | 0.9522 | 46.2 (12.8) | 0.9588 |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||||

| 20 to 30 | 2401 (12.2) | 4953 (12.6) | 166 (10.1) | 2235 (12.4) | 1162 (10.1) | |||

| >30 to 40 | 4544 (23.1) | 9097 (23.1) | 394 (23.9) | 4150 (23.0) | 2758 (23.9) | |||

| >40 to 50 | 5459 (27.7) | 11,088 (28.2) | 487 (29.5) | 4972 (27.6) | 3409 (29.5) | |||

| >50 to 60 | 3646 (18.5) | 7146 (18.2) | 330 (20.0) | 3316 (18.4) | 2310 (20.0) | |||

| >60 to 70 | 2737 (13.9) | 5316 (13.5) | 221 (13.4) | 2516 (14.0) | 1547 (13.4) | |||

| >70 | 886 (4.5) | 1746 (4.4) | 0.4047 | 53 (3.2) | 833 (4.6) | 0.0025 | 371 (3.2) | 1.0000 |

| Sex, females, n (%) | 13,654 (69.4) | 27,308 (69.4) | 1.0000 | 1309 (79.3) | 12,345 (68.5) | <0.0001 | 9163 (79.3) | 1.0000 |

| Region, n (%) | ||||||||

| Northern | 9694 (49.3) | 18,967 (48.2) | 741 (44.9) | 8953 (49.7) | 5187 (44.9) | |||

| Central | 4420 (22.5) | 8977 (22.8) | 424 (25.7) | 3996 (22.2) | 2986 (25.8) | |||

| Southern | 4601 (23.4) | 9304 (23.6) | 420 (25.4) | 4181 (23.2) | 2945 (25.5) | |||

| Eastern and other | 820 (4.2) | 1778 (4.5) | 52 (3.1) | 768 (4.3) | 364 (3.1) | |||

| Offshore islets | 138 (0.7) | 320 (0.8) | 0.0414 | 14 (0.8) | 124 (0.7) | <0.0001 | 75 (0.6) | 0.9297 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||||

| Disorders of lipoid metabolism | 7183 (36.5) | 10,174 (25.9) | <0.0001 | 435 (26.3) | 6748 (37.4) | <0.0001 | 4410 (38.2) | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 264 (1.3) | 311 (0.8) | <0.0001 | 14 (0.8) | 250 (1.4) | 0.0684 | 155 (1.3) | 0.0953 |

| Alcohol abuse | 281 (1.4) | 336 (0.9) | <0.0001 | 23 (1.4) | 258 (1.4) | 0.8996 | 145 (1.3) | 0.6387 |

| Hypertension | 9169 (46.6) | 15,010 (38.1) | <0.0001 | 746 (45.2) | 8423 (46.7) | 0.2261 | 5385 (46.6) | 0.2824 |

| Myocardial infarction | 127 (0.6) | 201 (0.5) | 0.0380 | 10 (0.6) | 117 (0.6) | 0.8327 | 85 (0.7) | 0.5594 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1089 (5.5) | 1462 (3.7) | <0.0001 | 97 (5.9) | 992 (5.5) | 0.5282 | 788 (6.8) | 0.1517 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 850 (4.3) | 1008 (2.6) | <0.0001 | 58 (3.5) | 792 (4.4) | 0.0917 | 623 (5.4) | 0.0012 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1914 (9.7) | 2874 (7.3) | <0.0001 | 144 (8.7) | 1770 (9.8) | 0.1491 | 1410 (12.2) | <0.0001 |

| Dementia | 237 (1.2) | 470 (1.2) | 0.9148 | 17 (1.0) | 220 (1.2) | 0.4958 | 174 (1.5) | 0.1297 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 4373 (22.2) | 5650 (14.4) | <0.0001 | 404 (24.5) | 3969 (22.0) | 0.0221 | 3196 (27.7) | 0.0066 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 6224 (31.6) | 7477 (19.0) | <0.0001 | 591 (35.8) | 5633 (31.3) | 0.0001 | 4574 (39.6) | 0.0032 |

| Mild liver disease | 4083 (20.8) | 4688 (11.9) | <0.0001 | 333 (20.2) | 3750 (20.8) | 0.5405 | 3000 (26) | <0.0001 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 33 (0.2) | 49 (0.1) | 0.1840 | 7 (0.4) | 26 (0.1) | 0.0079 | 20 (0.2) | 0.0347 |

| Diabetes (without chronic complication) | 2778 (14.1) | 4250 (10.8) | <0.0001 | 189 (11.4) | 2589 (14.4) | 0.0011 | 2071 (17.9) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes (with chronic complication) | 834 (4.2) | 1284 (3.3) | <0.0001 | 57 (3.5) | 777 (4.3) | 0.0973 | 622 (5.4) | 0.0009 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 381 (1.9) | 449 (1.1) | <0.0001 | 21 (1.3) | 360 (2.0) | 0.0406 | 298 (2.6) | 0.0012 |

| Renal disease | 789 (4.0) | 891 (2.3) | <0.0001 | 87 (5.3) | 702 (3.9) | 0.0064 | 529 (4.6) | 0.2121 |

| Any malignancy | 1053 (5.4) | 1642 (4.2) | <0.0001 | 157 (9.5) | 896 (5.0) | <0.0001 | 733 (6.3) | <0.0001 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 53 (0.3) | 76 (0.2) | 0.0615 | 10 (0.6) | 43 (0.2) | 0.0059 | 31 (0.3) | 0.0211 |

| Herpes Zoster/ Total Patients, % | Person-Years | Events per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up ≤1 year | |||||||

| Compared group | 15/39,346, 0.04 | 39,339.10 | 0.38 (0.38–0.39) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 246/19,673, 1.25 | 19,072.90 | 12.90 (12.72–13.08) | 33.83 (20.09–56.97) | <0.0001 | 30.42 (18.02–51.36) | <0.0001 |

| Follow-up >1 to 3 years * | |||||||

| Compared group | 163/39,331, 0.41 | 117,874.45 | 1.38 (1.37–1.39) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 445/18,386, 2.42 | 52,406.54 | 8.49 (8.42–8.56) | 6.14 (5.13–7.35) | <0.0001 | 5.61 (4.67–6.73) | <0.0001 |

| Follow-up >3 to 6 years * | |||||||

| Compared group | 777/39,168, 1.98 | 233,851.40 | 3.32 (3.31–3.34) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 588/15,582, 3.77 | 87,023.67 | 6.76 (6.71–6.80) | 2.03 (1.83–2.26) | <0.0001 | 1.80 (1.61–2.01) | <0.0001 |

| Overall | |||||||

| Compared group | 3903/39,346, 9.92 | 530,337.81 | 7.36 (7.34–7.38) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1857/19,673, 9.44 | 130,009.31 | 14.28 (14.21–14.36) | 1.94 (1.84–2.05) | <0.0001 | 1.74 (1.65–1.84) | <0.0001 |

| Herpes Zoster/ Total Patients, % | Person-Years | Events per 1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up ≤1 year | |||||||

| RA without CIC | 142/11,557, 1.23 | 11,191.86 | 12.69 (12.45–12.93) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| RA with CIC | 34/1651, 2.06 | 1604.88 | 21.19 (20.17–22.25) | 1.67 (1.15–2.43) | 0.0072 | 1.76 (1.21–2.57) | 0.0033 |

| Follow-up >1 to 3 years * | |||||||

| RA without CIC | 256/10,773, 2.38 | 30,604.27 | 8.36 (8.27–8.46) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| RA with CIC | 62/1550, 4.00 | 4427.16 | 14.00 (13.60–14.42) | 1.67 (1.27–2.21) | 0.0003 | 1.73 (1.31–2.29) | 0.0001 |

| Follow-up >3 to 6 years * | |||||||

| RA without CIC | 336/9052, 3.71 | 50,588.11 | 6.64 (6.58–6.70) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| RA with CIC | 84/1316, 6.38 | 7376.68 | 11.39 (11.13–11.65) | 1.71 (1.35–2.18) | <0.0001 | 1.85 (1.45–2.35) | <0.0001 |

| Overall | |||||||

| RA without CIC | 1055/11,557, 9.13 | 75,184.83 | 14.03 (13.93–14.13) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| RA with CIC | 259/1651, 15.69 | 11,798.50 | 21.95 (21.56–22.35) | 1.56 (1.37–1.79) | <0.0001 | 1.65 (1.44–1.89) | <0.0001 |

| Herpes Zoster Complications, n (%) | Herpes Zoster without Complication, n(%) | Total Patients | Herpes Zoster Complications | Herpes Zoster without Complication | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value | Crude HR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value | ||||

| Compared group | 952 (2.42) | 2951 (7.50) | 39,346 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| RA Patients | 550 (2.80) | 1307 (6.64) | 19,673 | 3.33 (2.96–3.74) | <0.0001 | 2.85 (2.53–3.21) | <0.0001 | 2.33 (2.17–2.49) | <0.0001 | 2.11 (1.96–2.26) | <0.0001 |

| RA group | |||||||||||

| RA without CIC | 310 (2.68) | 745 (6.45) | 11,557 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| RA with CIC | 80 (4.85) | 179 (10.84) | 1651 | 1.64 (1.28–2.10) | <0.0001 | 1.78 (1.39–2.29) | <0.0001 | 1.55 (1.31–1.82) | <0.0001 | 1.61 (1.37–1.90) | <0.0001 |

| Herpes Zoster | Non-Herpes Zoster | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 259 | 1392 | |

| Herpes zoster complications | |||

| Meningitis (ICD-9-CM 053.0), n (%) | 2 (0.8) | ||

| Nervous system complications (053.1), n (%) | 71 (27.4) | ||

| Ophthalmic complications (053.2), n (%) | 8 (3.1) | ||

| Age of cohort entry mean (SD), years | 50.0 (12.1) | 45.5 (12.9) | <0.0001 |

| Age group, n (%) | |||

| 20 to 30 | 12 (4.6) | 154 (11.1) | |

| >30 to 40 | 41 (15.8) | 353 (25.4) | |

| >40 to 50 | 78 (30.1) | 409 (29.4) | |

| >50 to 60 | 69 (26.6) | 261 (18.8) | |

| >60 to 70 | 48 (18.5) | 173 (12.4) | |

| >70 | 11 (4.2) | 42 (3.0) | <0.0001 |

| Sex, females, n (%) | 224 (86.5) | 1085 (78.0) | 0.0018 |

| Region, n (%) | |||

| Northern | 124 (47.9) | 617 (44.3) | |

| Central | 74 (28.6) | 350 (25.1) | |

| Southern | 48 (18.5) | 372 (26.7) | |

| Eastern and other | 10 (3.9) | 42 (3.0) | |

| Offshore islets | 3 (1.2) | 11 (0.8) | 0.0840 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Disorders of lipoid metabolism | 73 (28.2) | 362 (26.0) | 0.4647 |

| Obesity | 3 (1.2) | 11 (0.8) | 0.5531 |

| Alcohol abuse | 2 (0.8) | 21 (1.5) | 0.3532 |

| Hypertension | 134 (51.7) | 612 (44.0) | 0.0210 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (0.8) | 8 (0.6) | 0.7068 |

| Congestive heart failure | 20 (7.7) | 77 (5.5) | 0.1687 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7 (2.7) | 51 (3.7) | 0.4405 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 22 (8.5) | 122 (8.8) | 0.8875 |

| Dementia | 5 (1.9) | 12 (0.9) | 0.1178 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 79 (30.5) | 325 (23.3) | 0.0139 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 99 (38.2) | 492 (35.3) | 0.3748 |

| Mild liver disease | 56 (21.6) | 277 (19.9) | 0.5259 |

| Diabetes (without chronic complication) | 32 (12.4) | 157 (11.3) | 0.6173 |

| Diabetes (with chronic complication) | 9 (3.5) | 48 (3.4) | 0.9828 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 6 (2.3) | 15 (1.1) | 0.1023 |

| Renal disease | 18 (6.9) | 69 (5.0) | 0.1875 |

| Any malignancy | 27 (10.4) | 130 (9.3) | 0.5845 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) | 0.3476 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 2 (0.8) | 8 (0.6) | 0.7068 |

| Medications use (ATC code), n (%) | |||

| Corticosteroid use | |||

| Prednisolone (H02AB06) | 197 (76.1) | 946 (68.0) | 0.0095 |

| Methylprednisolone (H02AB04) | 32 (12.4) | 177 (12.7) | 0.8728 |

| Dexamethasone (H02AB02) | 63 (24.3) | 266 (19.1) | 0.0537 |

| Biopharmaceutical | |||

| Etanercept (L04AB01) | 24 (9.3) | 130 (9.3) | 0.9705 |

| Adalimumab (L04AB04) | 11 (4.2) | 58 (4.2) | 0.9526 |

| Rituximab (L01XC02) | 2 (0.8) | 11 (0.8) | 0.9760 |

| Combined biopharmaceutical use | 32 (12.4) | 180 (12.9) | 0.7992 |

| Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) | |||

| Azathioprine (L04AX01) | 17 (6.6) | 82 (5.9) | 0.6753 |

| Methotrexate (L01BA01) | 160 (61.8) | 836 (60.1) | 0.6037 |

| Sulfasalazine (A07EC01) | 170 (65.6) | 866 (62.2) | 0.2952 |

| Hydroxychloroquine (P01BA02) | 207 (79.9) | 1033 (74.2) | 0.0509 |

| Leflunomide (L04AA13) | 40 (15.4) | 268 (19.3) | 0.1485 |

| Ciclosporin (L04AA01) | 37 (14.3) | 185 (13.3) | 0.6663 |

| Combined DMARDs use | 227 (87.6) | 1154 (82.9) | 0.0581 |

| Other medications | |||

| Cyclophosphamide (L01AA01) | 9 (3.5) | 28 (2.0) | 0.1440 |

| Penicillamine (M01CC01) | 14 (5.4) | 69 (5.0) | 0.7616 |

| HZ | Non-HZ | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 259 | 1392 | ||||

| Model 1: Prednisolone (H02AB06), n (%) | ||||||

| No | 62 (23.9) | 446 (32.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 197 (76.1) | 946 (68.0) | 1.50 (1.10–2.04) | 0.0099 | 1.48 (1.08–2.03) | 0.0140 |

| Prednisolone use (days), n (%) | ||||||

| No use | 62 (23.9) | 446 (32.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| <172 | 43 (16.6) | 243 (17.5) | 1.27 (0.84–1.94) | 0.2592 | 1.31 (0.85–2.00) | 0.2189 |

| 173–668 | 48 (18.5) | 238 (17.1) | 1.45 (0.96–2.18) | 0.0741 | 1.51 (0.99–2.29) | 0.0520 |

| 669–1795 | 38 (14.7) | 248 (17.8) | 1.10 (0.72–1.7) | 0.6592 | 1.05 (0.68–1.63) | 0.8340 |

| >1795 | 68 (26.3) | 217 (15.6) | 2.25 (1.54–3.3) | <0.0001 | 2.16 (1.46–3.19) | 0.0001 |

| Per 1 year * | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 0.0026 | 1.06 (1.02–1.12) | 0.0098 | ||

| Prednisolone use (dosages, mg), n (%) | ||||||

| No use | 62 (23.9) | 446 (32.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| <1050 | 43 (16.6) | 245 (17.6) | 1.26 (0.83–1.92) | 0.2755 | 1.29 (0.84–1.98) | 0.2375 |

| 1051–3990 | 45 (17.4) | 239 (17.2) | 1.35 (0.89–2.05) | 0.1517 | 1.39 (0.91–2.11) | 0.1302 |

| 3990–10995 | 46 (17.8) | 240 (17.2) | 1.38 (0.91–2.08) | 0.1269 | 1.33 (0.87–2.02) | 0.1864 |

| >10995 | 63 (24.3) | 222 (15.9) | 2.04 (1.39–3.00) | 0.0003 | 1.95 (1.31–2.89) | 0.0009 |

| Per 1825 mg/year | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.0097 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.0156 | ||

| Model 2: Combined biopharmaceutical and prednisolone | ||||||

| No/No | 60 (23.2) | 427 (30.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes/No | 2 (0.8) | 19 (1.4) | 0.75 (0.17–3.30) | 0.7024 | 0.76 (0.17–3.39) | 0.7217 |

| No/Yes | 167 (64.5) | 785 (56.4) | 1.51 (1.10–2.08) | 0.0105 | 1.50 (1.08–2.07) | 0.0146 |

| Yes/Yes | 30 (11.6) | 161 (11.6) | 1.33 (0.83–2.13) | 0.2435 | 1.31 (0.81–2.12) | 0.2740 |

| Model 3: Combined DMARDs and prednisolone | ||||||

| No/No | 26 (10.0) | 206 (14.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes/No | 36 (13.9) | 240 (17.2) | 1.19 (0.69–2.03) | 0.5291 | 1.23 (0.71–2.13) | 0.4638 |

| No/Yes | 6 (2.3) | 32 (2.3) | 1.49 (0.57–3.89) | 0.4203 | 1.51 (0.57–4.02) | 0.4122 |

| Yes/Yes | 191 (73.7) | 914 (65.7) | 1.66 (1.07–2.56) | 0.0236 | 1.67 (1.07–2.60) | 0.0249 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dlamini, S.T.; Htet, K.M.; Theint, E.C.C.; Mayadilanuari, A.M.; Li, W.-M.; Tung, Y.-C.; Tu, H.-P. Herpes Zoster Risk in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Its Association with Medications Used. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032123

Dlamini ST, Htet KM, Theint ECC, Mayadilanuari AM, Li W-M, Tung Y-C, Tu H-P. Herpes Zoster Risk in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Its Association with Medications Used. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032123

Chicago/Turabian StyleDlamini, Sithembiso Tiyandza, Kyaw Moe Htet, Ei Chue Chue Theint, Aerrosa Murenda Mayadilanuari, Wei-Ming Li, Yi-Ching Tung, and Hung-Pin Tu. 2023. "Herpes Zoster Risk in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Its Association with Medications Used" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032123

APA StyleDlamini, S. T., Htet, K. M., Theint, E. C. C., Mayadilanuari, A. M., Li, W.-M., Tung, Y.-C., & Tu, H.-P. (2023). Herpes Zoster Risk in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Its Association with Medications Used. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032123