The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Adults Aged 35–60 Years: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Sample

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Depressive Symptoms

2.2.2. Job Satisfaction

2.2.3. Subjective Well-Being

2.2.4. Life Satisfaction

2.2.5. Other Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Samples

3.2. Correlation of Job Satisfaction, Subjective Well-Being, Life Satisfaction, and Depressive Symptoms

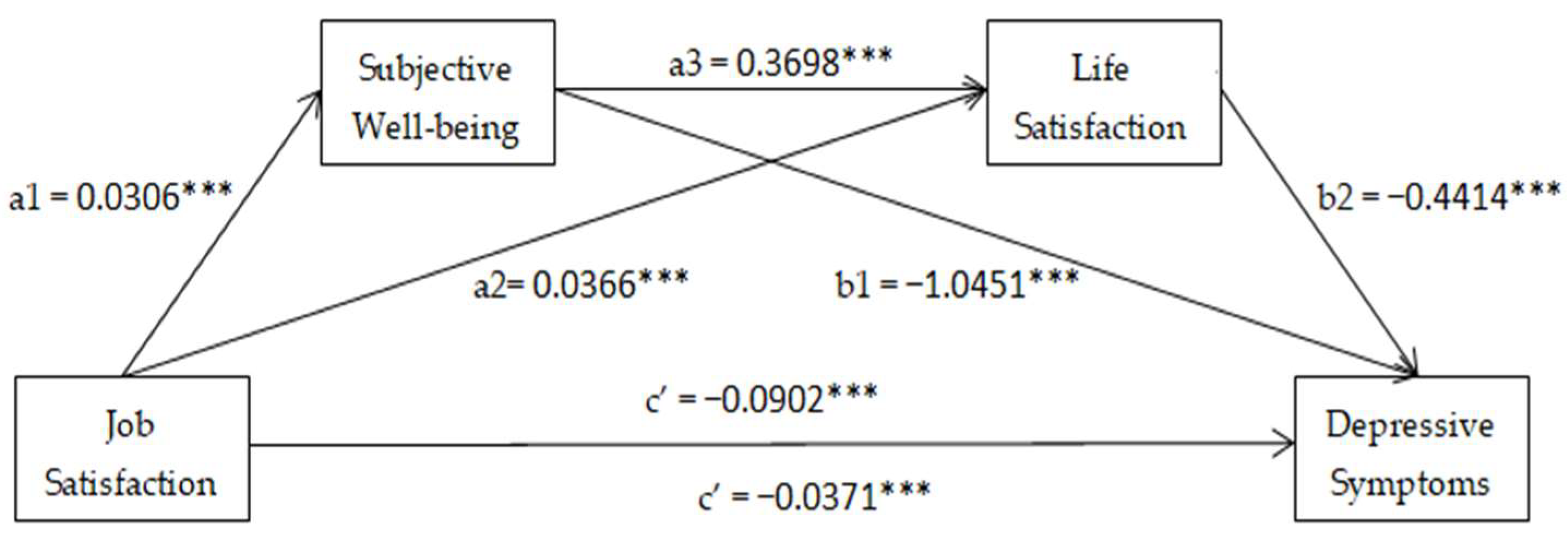

3.3. Mediation Analysis of Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction

4. Discussion

4.1. The Direct Effect of Job Satisfaction on Depressive Symptoms

4.2. The Mediation Effect of Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferrari, A.J.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Patten, S.B.; Freedman, G.; Murray, C.J.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.S.H.; Tan, E.L.Y.; Ho, R.C.M.; Chiu, M.Y.L. Relationship of Anxiety and Depression with Respiratory Symptoms: Comparison between Depressed and Non-Depressed Smokers in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, B.X.; Ha, G.H.; Nguyen, D.N.; Nguyen, T.P.; Do, H.T.; Latkin, C.A.; Ho, C.S.H.; Ho, R.C.M. Global mapping of interventions to improve quality of life of patients with depression during 1990-2018. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 2333–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, A.H.; Gbedemah, M.; Martinez, A.M.; Nash, D.; Galea, S.; Goodwin, R.D. Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: Widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, A.; Thom, J.; Jacobi, F.; Holstiege, J.; Bätzing, J. Trends in prevalence of depression in Germany between 2009 and 2017 based on nationwide ambulatory claims data. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 271, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.E.; Jo, M.W.; Shin, Y.W. Increased prevalence of depression in South Korea from 2002 to 2013. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Sun, X.; Strauss, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, Y. Depressive symptoms and SES among the mid-aged and elderly in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study national baseline. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 120, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Fan, L.; Yin, Z. Association between family socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: Evidence from a national household survey. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 259, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, K. Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages Summary Chart: Stages of Psychosocial Development. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/erik-eriksons-stages-of-psychosocial-development-2795740 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Guo, X. Longitudinal Dyadic Associations between Depressive Symptoms and Life Satisfaction among Chinese Married Couples and the Moderating Effect of Within-Dyad Age Discrepancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altiok, M.; Yilmaz, M.; Onal, P.; Akturk, F.; Temel, G.O. Relationship between Activities of Daily Living, Sleep and Depression among the Aged Living at Home. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 28, 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, D.E.; Malhotra, S.; Franco, K.N.; Tesar, G.; Bronson, D.L. Heart disease and depression: Don’t ignore the relationship. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2003, 70, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussavi, S.; Chatterji, S.; Verdes, E.; Tandon, A.; Patel, V.; Ustun, B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007, 370, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M. Gender disparities and depressive symptoms over the life course and across cohorts in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeom, H.E.; Kim, Y.J. Age and sex-specific associations between depressive symptoms, body mass index and cognitive functioning among Korean middle-aged and older adults: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungberg, T.; Bondza, E.; Lethin, C. Evidence of the Importance of Dietary Habits Regarding Depressive Symptoms and Depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandola, A.; Ashdown-Franks, G.; Hendrikse, J.; Sabiston, C.M.; Stubbs, B. Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.H.; Zhu, F.; Qin, T.T. Relationships between Chronic Diseases and Depression among Middle-aged and Elderly People in China: A Prospective Study from CHARLS. Curr. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Y.S.; Segel-Karpas, D. Aging anxiety, loneliness, and depressive symptoms among middle-aged adults: The moderating role of ageism. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 290, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Sun, H.; Zhu, B.; Yu, X.; Niu, Y.; Kou, C.; Li, W. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and its determinants among adults in mainland China: Results from a national household survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zheng, P.; Liu, B.; Guo, Z.; Geng, S.; Hong, S. Life negative events and depressive symptoms: The China longitudinal ageing social survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chai, D. Objective Work-Related Factors, Job Satisfaction and Depression: An Empirical Study among Internal Migrants in China. Healthcare 2020, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. The Role of Psychological Well-Being in Job Performance: A Fresh Look at an Age-Old Quest. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, S.; Shafipour, V.; Taraghi, Z.; Yazdani-Charati, J. Relationship between moral distress and ethical climate with job satisfaction in nurses. Nurs. Ethics 2019, 26, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faragher, E.B.; Cass, M.; Cooper, C.L. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: A meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, M.C.C.; Oliva, C.C.C.; Bezerra, N.M.S.; Silva, M.T.; Galvão, T.F. Relationship between depressive symptoms, burnout, job satisfaction and patient safety culture among workers at a university hospital in the Brazilian Amazon region: Cross-sectional study with structural equation modeling. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Lázaro-Illatopa, W.I.; Castillo-Blanco, R.; Cabieses, B.; Blukacz, A.; Bellido-Boza, L.; Mezones-Holguin, E. Relationship between job satisfaction, burnout syndrome and depressive symptoms in physicians: A cross-sectional study based on the employment demand-control model using structural equation modelling. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, B.; Huang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cai, F. Prevalence and influencing factors of depressive symptoms among rural-to-urban migrant workers in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 307, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsuse, T.; Sekine, M.; Yamada, M. The Contributions Made by Job Satisfaction and Psychosocial Stress to the Development and Persistence of Depressive Symptoms: A 1-Year Prospective Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonde, J.P. Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: A systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008, 65, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, M.; Caspi, A.; Milne, B.J.; Danese, A.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E. Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Patten, S.B. Perceived work stress and major depression in the Canadian employed population, 20–49 years old. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, S.; Lees, T.; Lal, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in a Cohort of Australian Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.M.; Silva, M.T.; Galvão, T.F.; Lopes, L.C. The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout syndrome and depressive symptoms: An analysis of professionals in a teaching hospital in Brazil. Medicine 2018, 97, e13364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, E.H.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Yoon, H.J. Life satisfaction and happiness associated with depressive symptoms among university students: A cross-sectional study in Korea. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2018, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, C.W.; Yang, H.F.; Huang, W.T.; Fan, S.Y. The Relationships between Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction and Happiness among Young, Middle-Aged, and Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satuf, C.; Monteiro, S.; Pereira, H.; Esgalhado, G.; Marina Afonso, R.; Loureiro, M. The protective effect of job satisfaction in health, happiness, well-being and self-esteem. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2018, 24, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.M.; Xia, L. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Chinese Residents’SWB: A Comprehensive Analytical Framework. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2014, 12–19, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N.; Truxillo, D.M.; Mansfield, L.R. Whistle While You Work: A Review of the Life Satisfaction Literature. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1038–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carandang, R.R.; Shibanuma, A.; Kiriya, J.; Asis, E.; Chavez, D.C.; Meana, M.; Murayama, H.; Jimba, M. Determinants of depressive symptoms in Filipino senior citizens of the community-based ENGAGE study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 82, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Guo, X.; Ren, Z.; Li, X.; He, M.; Shi, H.; Zha, S.; Qiao, S.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; et al. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors in middle-aged and elderly Chinese people. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; He, X.; Pan, D.; Qiao, H.; Li, J. Happiness, depression, physical activity and cognition among the middle and old-aged population in China: A conditional process analysis. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magen, Z. Commitment beyond self and adolescence: The issue of happiness. Soc. Indic. Res. 1996, 37, 235–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Dexter, C.; Kinsey, R.; Parker, S. Meaningful work and mental health: Job satisfaction as a moderator. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q. Chinese university teachers’ job and life satisfaction: Examining the roles of basic psychological needs satisfaction and self-efficacy. J. Gen. Psychol. 2022, 149, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Koopmann, J.; Wang, M.; Chang, C.D.; Shi, J. Eating your feelings? Testing a model of employees’ work-related stressors, sleep quality, and unhealthy eating. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 1237–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Feng, D. Mediating role of occupational stress and job satisfaction on the relationship between neuroticism and quality of life among Chinese civil servants: A structural equation model. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosella, L.C.; Fu, L.; Buajitti, E.; Goel, V. Death and Chronic Disease Risk Associated With Poor Life Satisfaction: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, M.E.; Işik, E. Positive and negative affect, life satisfaction, and coping with stress by attachment styles in Turkish students. Psychol. Rep. 2010, 107, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Qin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Gao, T.; Ren, H.; Hu, Y.; Cao, R.; Liang, L.; Li, C.; Tong, Q. Influence of Life Satisfaction on Quality of Life: Mediating Roles of Depression and Anxiety Among Cardiovascular Disease Patients. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.; Kuykendall, L. Promoting happiness: The malleability of individual and societal subjective wellbeing. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronk, N.P.; Kottke, T.E.; Lowry, M.; Katz, A.S.; Gallagher, J.M.; Knudson, S.M.; Rauri, S.J.; Tillema, J.O. Concordance Between Life Satisfaction and Six Elements of Well-Being Among Respondents to a Health Assessment Survey, HealthPartners Employees, Minnesota, 2011. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2016, 13, E173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, B.; Chen, H.; Lu, T.; Yan, J. The Effect of Physical Exercise and Internet Use on Youth Subjective Well-Being-The Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction and the Moderating Effect of Social Mentality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milovanska-Farrington, S.; Farrington, S. Happiness, domains of life satisfaction, perceptions, and valuation differences across genders. Acta Psychol. 2022, 230, 103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heyden, K.; Dezutter, J.; Beyers, W. Meaning in Life and depressive symptoms: A person-oriented approach in residential and community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.E.; Vernon, S.W. The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale—Its use in a community sample. Am. J. Psychiatry 1983, 140, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eikemo, T.A.; Bambra, C.; Huijts, T.; Fitzgerald, R. The First Pan-European Sociological Health Inequalities Survey of the General Population: The European Social Survey Rotating Module on the Social Determinants of Health. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 33, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, H.; Ren, Z.; He, M.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Pu, Y.; Cui, L.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; et al. The Mediating Role of Extra-family Social Relationship Between Personality and Depressive Symptoms Among Chinese Adults. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Cheng, G.; Wu, X.; Li, R.; Li, C.; Tian, G.; He, S.; Yan, Y. The Associations between Sleep Duration, Academic Pressure, and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Adolescents: Results from China Family Panel Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missinne, S.; Vandeviver, C.; Van de Velde, S.; Bracke, P. Measurement equivalence of the CES-D 8 depression-scale among the ageing population in eleven European countries. Soc. Sci. Res. 2014, 46, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, P.; Huang, X. The Influence of Mental Health on Job Satisfaction: Mediating Effect of Psychological Capital and Social Capital. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 797274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akuffo, K.O.; Asare, A.K.; Yelbert, E.E.; Kobia-Acquah, E.; Addo, E.K.; Agyei-Manu, E.; Brusah, T.; Asenso, P.A. Job satisfaction and its associated factors among opticians in Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, C. The subjective well-being effect of public goods provided by village collectives: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterlin, R.A. Explaining happiness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11176–11183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Miao, G.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, S. Relationship between Children’s Intergenerational Emotional Support and Subjective Well-Being among Middle-Aged and Elderly People in China: The Mediation Role of the Sense of Social Fairness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Chen, J.K. Association of Received Intergenerational Support with Subjective Well-Being among Elderly: The Mediating Role of Optimism and Sex Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.; Lucas, R.E. Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: Results from three large samples. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 2809–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sun, H.; Xu, W.; Ma, W.; Yuan, X.; Niu, Y.; Kou, C. Individual Social Capital and Life Satisfaction among Mainland Chinese Adults: Based on the 2016 China Family Panel Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K.; Hakanen, J. Job strain, burnout, and depressive symptoms: A prospective study among dentists. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 104, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K.; Honkonen, T.; Isometsa, E.; Kalimo, R.; Nykyri, E.; Aromaa, A.; Lonnqvist, J. The relationship between job-related burnout and depressive disorders-results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 88, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cass, M.H.; Siu, O.L.; Faragher, E.B.; Cooper, C.L. A meta-analysis of the relationship between job satisfaction and employee health in Hong Kong. Stress Health 2003, 19, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehan, C.L.; Wiggins, M. Colorado-Denver. Responding to and Retreating from the Call: Career Salience, Work Satisfaction, and Depression among Clergywomen. Pastor. Psychol. 2007, 55, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.C.; Doerpinghaus, H.I.; Turnley, W.H. Managing temporary workers—A permanent hrm challenge. Organ. Dyn. 1994, 23, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadden, W.C.; Muntaner, C.; Benach, J.; Gimeno, D.; Benavides, F.G. A glossary for the social epidemiology of work organisation: Part 3, terms from the sociology of labour markets. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I. Globalization and workers’ health. Ind. Health 2008, 46, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloniemi, A.; Virtanen, P.; Vahtera, J. The work environment in fixed-term jobs: Are poor psychosocial conditions inevitable? Work. Employ. Soc. 2004, 18, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, T.H.; Ju, Y.J.; Chun, S.Y.; Park, E.C. Temporary work and depressive symptoms in South Korean workers. Occup. Med. 2017, 67, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The Relationship Between Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, M.A.; Alkhaili, M.; Aldhaheri, H.; Yang, G.; Albahar, M.; Alrashdi, A. Exploring the Reciprocal Relationships between Happiness and Life Satisfaction of Working Adults-Evidence from Abu Dhabi. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, E.J.; Trivedi, M.H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Gaynes, B.N.; Warden, D.; Morris, D.W.; Luther, J.F.; Farabaugh, A.; Cook, I.; et al. Health-related quality of life in depression: A STAR*D report. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duffy, R.D.; Allan, B.A.; Autin, K.L.; Bott, E.M. Calling and life satisfaction: It’s not about having it, it’s about living it. J. Couns Psychol. 2013, 60, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, N.A.; Eschleman, K.J.; Wang, Q. A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring Meaningful Work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, M. Life Satisfaction and Depression in the Oldest Old: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2020, 91, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.A.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; McKee, M.C. Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, E.H.; Snippe, E.; de Jonge, P.; Jeronimus, B.F. Preserving Subjective Wellbeing in the Face of Psychopathology: Buffering Effects of Personal Strengths and Resources. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | N | Mean ± SD /Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 47.91 ± 6.88 | ||

| Gender | Female | 5202 | 49.0 |

| Male | 5407 | 51.0 | |

| Self-reported health | Very unhealthy | 1700 | 16.0 |

| Unhealthy | 1590 | 15.0 | |

| General | 4567 | 43.0 | |

| Healthy | 1351 | 12.7 | |

| Very healthy | 1401 | 13.2 | |

| Marital status | Not married | 531 | 5.0 |

| Married | 10,078 | 95.0 |

| Variables | Job Satisfaction | Subjective Well-Being | Life Satisfaction | Depressive Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | 1 | |||

| Subjective well-being | 0.144 *** | 1 | ||

| Life satisfaction | 0.228 *** | 0.398 *** | 1 | |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.109 *** | −0.321 *** | −0.230 *** | 1 |

| Variables | Depressive Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| B | t | p | B | t | p | |

| Job satisfaction | −0.134 | −16.113 | <0.001 | −0.0902 | −11.3296 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.0117 | −2.2350 | 0.0254 | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1 | |||||

| Male | −0.8347 | −11.5946 | <0.001 | |||

| Self-reported health | 0.9671 | 31.4952 | <0.001 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Not married | 1 | |||||

| Married | −1.7920 | −10.9014 | <0.001 | |||

| Pathway | Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect (c) | −0.0902 | 0.008 | −0.1058 | −0.0746 |

| Direct effect (c’) | −0.0371 | 0.0083 | −0.0531 | −0.0206 |

| a1 | 0.0306 | 0.0022 | 0.0264 | 0.0348 |

| a2 | 0.0366 | 0.0021 | 0.0327 | 0.0407 |

| a3 | 0.3698 | 0.0108 | 0.3483 | 0.3905 |

| b1 | −1.0451 | 0.0434 | −1.1301 | −0.9607 |

| b2 | −0.4414 | 0.0438 | −0.5292 | −0.3578 |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Total indirect effects | −0.0531 | 0.0034 | −0.0600 | −0.0468 |

| Indirect 1 | −0.032 | 0.0026 | −0.0373 | −0.0270 |

| Indirect 2 | −0.0162 | 0.0019 | −0.0200 | −0.0126 |

| Indirect 3 | −0.005 | 0.0006 | −0.0063 | −0.0038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, S. The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Adults Aged 35–60 Years: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032023

Liu Y, Yang X, Wu Y, Xu Y, Zhong Y, Yang S. The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Adults Aged 35–60 Years: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032023

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yixuan, Xinyan Yang, Yinghui Wu, Yanling Xu, Yiwei Zhong, and Shujuan Yang. 2023. "The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Adults Aged 35–60 Years: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032023

APA StyleLiu, Y., Yang, X., Wu, Y., Xu, Y., Zhong, Y., & Yang, S. (2023). The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Adults Aged 35–60 Years: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032023