How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affects the Provision of Psychotherapy: Results from Three Online Surveys on Austrian Psychotherapists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Sociodemographic Variables

2.1.2. Number of Patients Treated and Psychotherapeutic Format

2.1.3. Effects of the Pandemic on Psychotherapeutic Work and Wishes for Support with Professional Activities

2.2. Statistical Analyses

2.3. Content Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample Characteristics

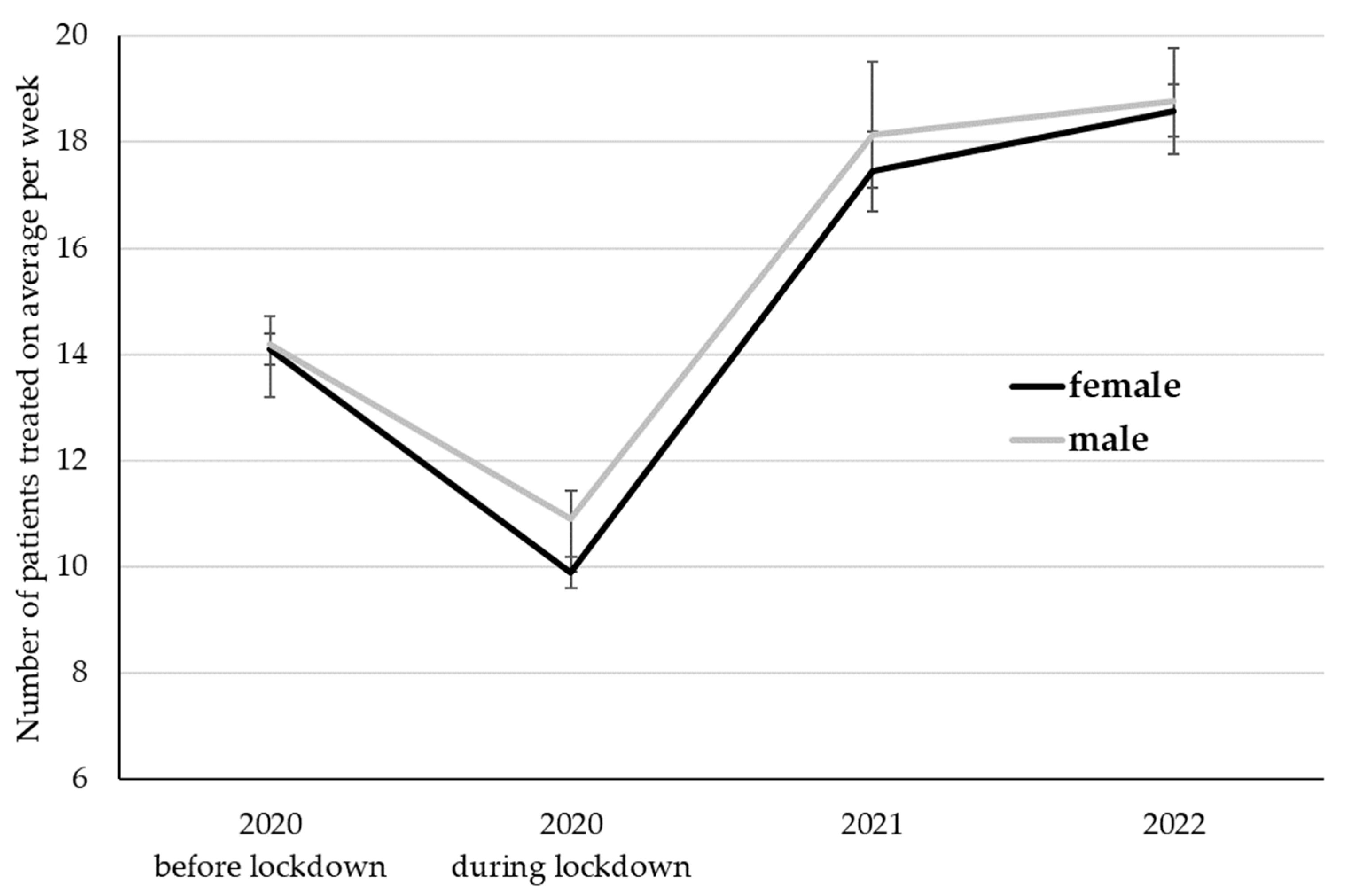

3.2. Changes in the Total Number of Patients

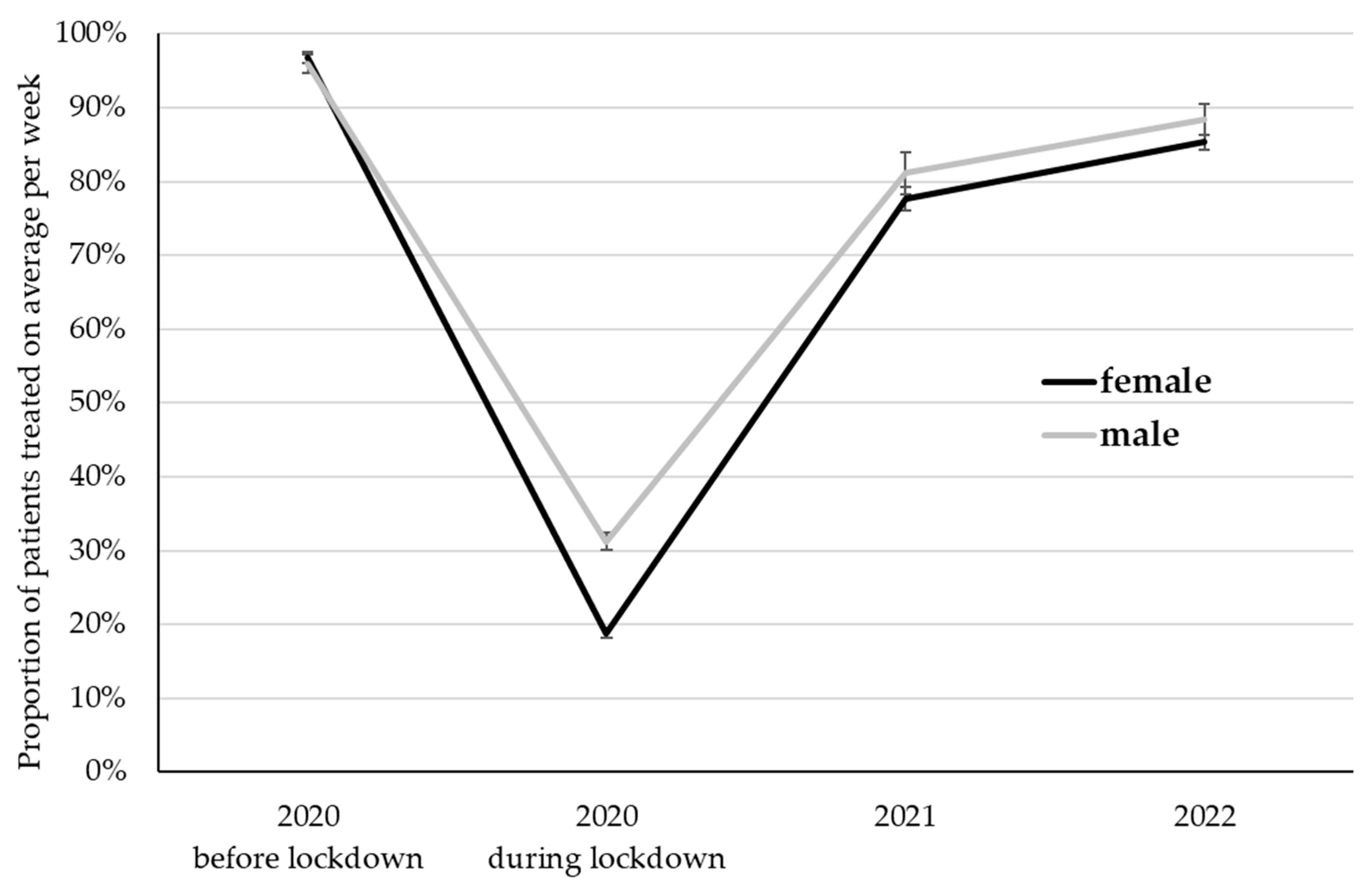

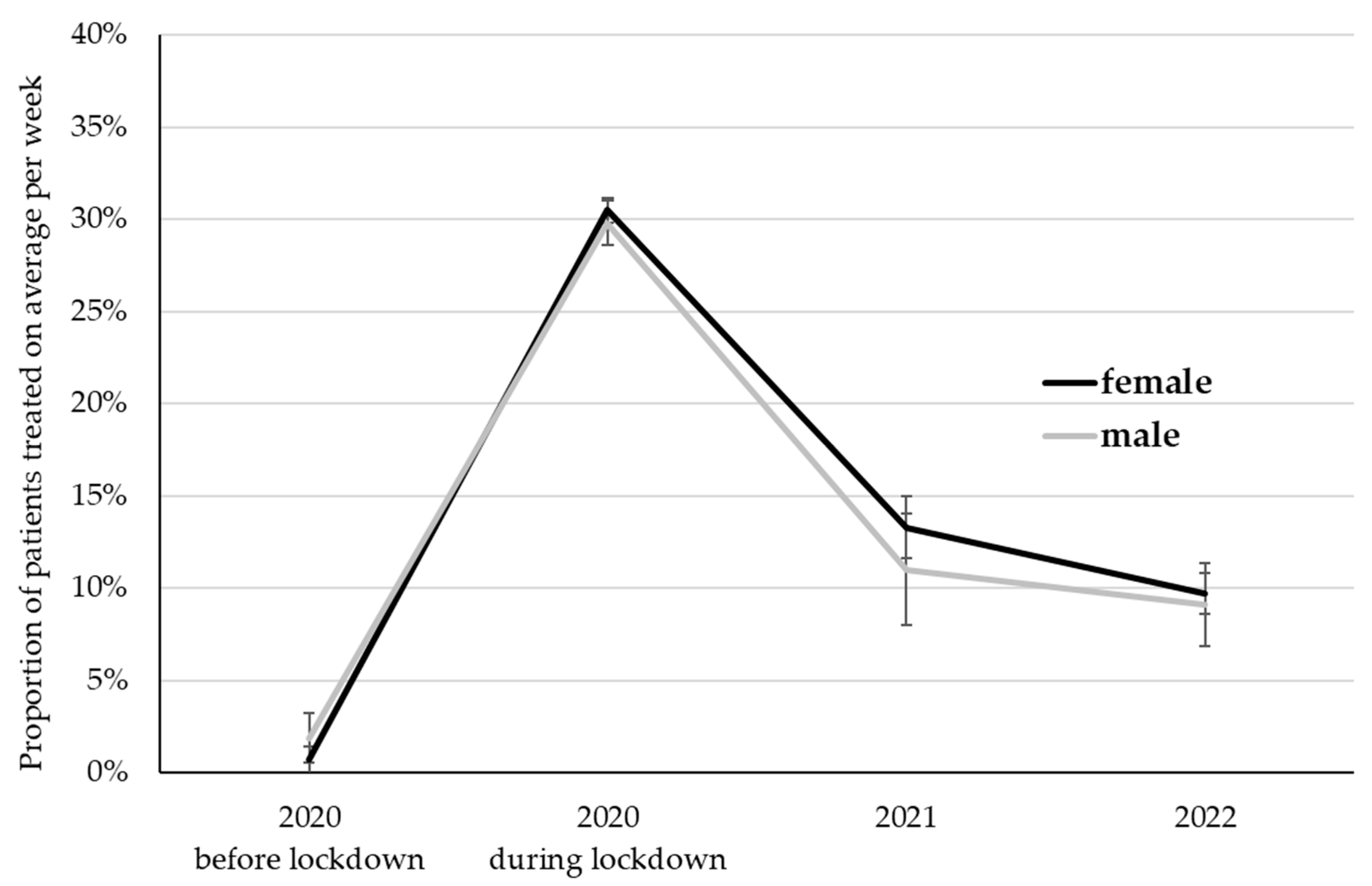

3.3. Changes in Treatment Format

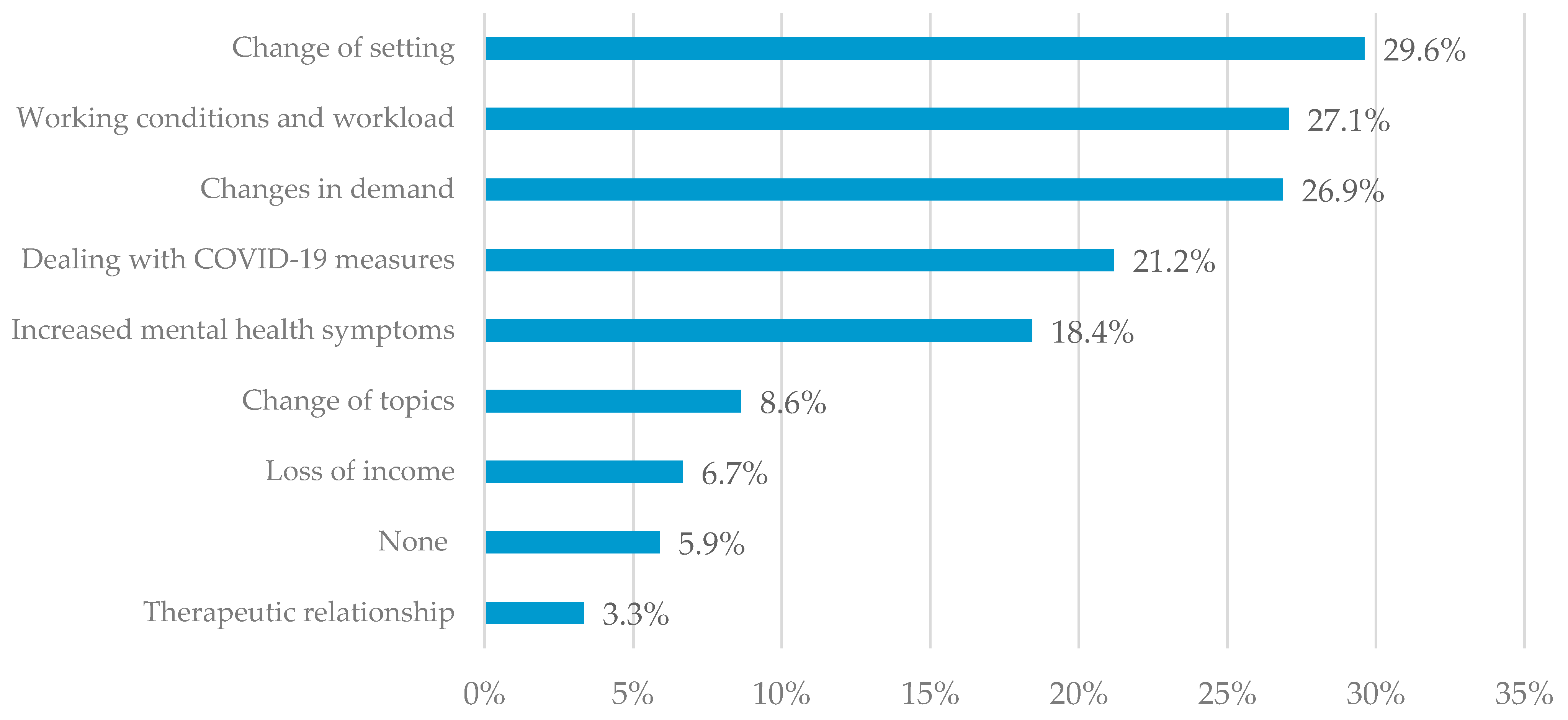

3.4. Free-Text Answers on Experienced Changes in Psychotherapeutic Work

“Patients, after periods of doubt, enjoyed online psychotherapy very much, and the effect is 100% equal to that in face-to-face”.(Case 329)

“I found the therapeutic work via Zoom much more exhausting and less effective than face-to-face contact. Some interventions were not possible via Zoom”.(Case 410)

“My facial expressions are missed by the clients; eating disorders are recognized much later, hiding behind the mask”.(Case 38)

“I have noticed a massive deterioration in depressed and eating disordered clients and increased stress in very young people who were previously completely free of symptoms”.(Case 153)

“The simultaneousness of the shared experience, but with very different attitudes towards them, sometimes caused anger against patients, e.g., when they worried about compulsory tests for skiing or about measures and vaccinations in general. To always maintain professional restraint in such cases was almost equivalent to self-harm for me over time“.(Case 475)

“At the beginning, I had big financial losses. Currently, it has decreased, but I have at least 3–5 cancellations per week”.(Case 136)

“Due to wearing a mask, loss of mimic for expressing emotions. On the other hand, stress reduction for clients with personality disorders… dissociative symptoms”.(Case 256)

“More bonding with the clients “we are all in the same boat”.(Case 149)

3.5. Free-Text Answers on Wishes for Support in Psychotherapeutic Work

“I feel that, for financial reasons, patients only seek psychotherapy when the subjective sense of a disorder is already very severe. Many clients for whom psychotherapy would be essential cannot yet afford it“.(Case 353)

“Exchange forums for dealing with the current situation“.(Case 179)

“Keynotes or something similar on current topics (cross-school networking) (e.g., dealing with the pandemic), easy and low-threshold access possible especially via the use of video telephony”.(Case 234)

“More exchange and cohesion instead of competition”.(Case 344)

“A contact to which one can turn, for example, regarding newly prescribed measures. ÖBVP and VÖPP were and are only of limited help”.(Case 102)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wind, T.R.; Rijkeboer, M.; Andersson, G.; Riper, H. The COVID-19 Pandemic: The ‘Black Swan’ for Mental Health Care and a Turning Point for e-Health. Internet Interv. 2020, 20, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humer, E.; Probst, T. Provision of Remote Psychotherapy during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Digit. Psychol. 2020, 1, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteveen, A.B.; Young, S.; Cuijpers, P.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Barbui, C.; Bertolini, F.; Cabello, M.; Cadorin, C.; Downes, N.; Franzoi, D.; et al. Remote Mental Health Care Interventions during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Umbrella Review. Behav. Res. Ther. 2022, 159, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of Stress, Anxiety, Depression among the General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, S.; Mohsin, M.; Dewan, M.N.; Muyeed, A. The Global Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Insomnia Among General Population During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trends Psychol. 2022, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieh, C.; Budimir, S.; Probst, T. The Effect of Age, Gender, Income, Work, and Physical Activity on Mental Health during Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Lockdown in Austria. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 136, 110186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.; Stippl, P.; Pieh, C. Changes in Provision of Psychotherapy in the Early Weeks of the COVID-19 Lockdown in Austria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, S.L.; Miller, C.J.; Lindsay, J.A.; Bauer, M.S. A Systematic Review of Providers’ Attitudes toward Telemental Health via Videoconferencing. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vis, C.; Mol, M.; Kleiboer, A.; Bührmann, L.; Finch, T.; Smit, J.; Riper, H. Improving Implementation of EMental Health for Mood Disorders in Routine Practice: Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitating Factors. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, P.W.; Keller, S.M.; Acierno, R. Treatment for Anxiety and Depression via Clinical Videoconferencing: Evidence Base and Barriers to Expanded Access in Practice. Focus 2018, 16, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, E.; Haid, B.; Schimböck, W.; Reisinger, A.; Gasser, M.; Eichberger-Heckmann, H.; Stippl, P.; Pieh, C.; Probst, T. Provision of Psychotherapy One Year after the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humer, E.; Pieh, C.; Kuska, M.; Barke, A.; Doering, B.K.; Gossmann, K.; Trnka, R.; Meier, Z.; Kascakova, N.; Tavel, P.; et al. Provision of Psychotherapy during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Czech, German and Slovak Psychotherapists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humer, E.; Stippl, P.; Pieh, C.; Pryss, R.; Probst, T. Experiences of Psychotherapists With Remote Psychotherapy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, E.; Stippl, P.; Pieh, C.; Schimböck, W.; Probst, T. Psychotherapy via the Internet: What Programs Do Psychotherapists Use, How Well-Informed Do They Feel, and What Are Their Wishes for Continuous Education? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blog 51-Chronology of the Corona Crisis in Austria-Part 1: Background, the Way to the Lockdown, the Acute Phase and Economic Consequences. Available online: https://viecer.univie.ac.at/en/projects-and-cooperations/austrian-corona-panel-project/corona-blog/corona-blog-beitraege/blog51/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Probst, T.; Humer, E.; Stippl, P.; Pieh, C. Being a Psychotherapist in Times of the Novel Coronavirus Disease: Stress-Level, Job Anxiety, and Fear of Coronavirus Disease Infection in More Than 1,500 Psychotherapists in Austria. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 559100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blog 112 (EN)-Chronology of the Corona Crisis in Austria-Part 5: Third Wave, Regional Lockdowns and the Vaccination Campaign. Available online: https://viecer.univie.ac.at/en/projects-and-cooperations/austrian-corona-panel-project/corona-blog/corona-blog-beitraege/blog112-en/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Jesser, A.; Humer, E.; Barke, A.; Doering, B.K.; Haid, B.; Schimböck, W.; Reisinger, A.; Gasser, M.; Eichberger-Heckmann, H.; et al. A Web-Survey Assessed Attitudes toward Evidence-Based Practice among Psychotherapists in Austria. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.; Humer, E.; Jesser, A.; Pieh, C. Attitudes of Psychotherapists towards Their Own Performance and the Role of the Social Comparison Group: The Self-Assessment Bias in Psychodynamic, Humanistic, Systemic, and Behavioral Therapists. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 966947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blog 150-Chronologie zur Corona-Krise in Österreich-Teil 7: Der Delta-Lockdown, die Omikron-Welle und das “Frühlingserwachen”. Available online: https://viecer.univie.ac.at/corona-blog/corona-blog-beitraege/blog-150-chronologie-zur-corona-krise-in-oesterreich-teil-7-der-delta-lockdown-die-omikron-welle-und-das-fruehlingserwachen/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Schaffler, Y.; Kaltschik, S.; Probst, T.; Jesser, A.; Pieh, C.; Humer, E. Mental Health in Austrian Psychotherapists during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1011539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, K.-E. The Situation of Psychotherapy in Austria. Available online: http://www.europsyche.org/situation-of-psychotherapy-in-various-countries/austria/ (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Crowe, M.; Inder, M.; Porter, R. Conducting Qualitative Research in Mental Health: Thematic and Content Analyses. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS.Ti 22 Windows; ATLAS.Ti Scientific Software Development GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2022.

- Dale, R.; Budimir, S.; Probst, T.; Stippl, P.; Pieh, C. Mental Health during the COVID-19 Lockdown over the Christmas Period in Austria and the Effects of Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, E.; Schaffler, Y.; Jesser, A.; Probst, T.; Pieh, C. Mental Health in the Austrian General Population during COVID-19: Cross-Sectional Study on the Association with Sociodemographic Factors. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 943303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Sagar, R. Online Psychotherapy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2022, 44, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, G.; Basu, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Craske, M.G.; McEvoy, P.; English, C.L.; Newby, J.M. Computer Therapy for the Anxiety and Depression Disorders Is Effective, Acceptable and Practical Health Care: An Updated Meta-Analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018, 55, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Sanger, N.; Singhal, N.; Pattrick, K.; Shams, I.; Shahid, H.; Hoang, P.; Schmidt, J.; Lee, J.; Haber, S.; et al. A Comparison of Electronically-Delivered and Face to Face Cognitive Behavioural Therapies in Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 24, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesser, A.; Muckenhuber, J.; Lunglmayr, B.; Dale, R.; Humer, E. Provision of Psychodynamic Psychotherapy in Austria during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S. Psychotherapy via Videoconferencing: A Review. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2009, 37, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.; Bell, L.; Knox, J.; Mitchell, D. Therapy via Videoconferencing: A Route to Client Empowerment? Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2005, 12, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.; Knox, J.; Mitchell, D.; Ferguson, J.; Brebner, J.; Brebner, E. A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Treatment of Eating Disorders via Videoconferencing in North-East Scotland. J. Telemed. Telecare 2003, 9, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coroiu, A.; Moran, C.; Campbell, T.; Geller, A.C. Barriers and Facilitators of Adherence to Social Distancing Recommendations during COVID-19 among a Large International Sample of Adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Harris, E.A.; Heemskerk, A.; Van Bavel, J.J.; Ebner, N.C. A Multi-National Test on Self-Reported Compliance with COVID-19 Public Health Measures: The Role of Individual Age and Gender Demographics and Countries’ Developmental Status. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 286, 114335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffler, Y.; Probst, T.; Jesser, A.; Humer, E.; Pieh, C.; Stippl, P.; Haid, B.; Schigl, B. Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Psychotherapy Utilisation and How They Relate to Patient’s Psychotherapeutic Goals. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schigl, B.; Lerch, L.; Rohner, J. Erfahrungen von Wiener Psychotherapeut_innen mit der Antragstellung und Bewilligungspraxis der Krankenkassen. Psychother. Forum 2021, 25, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 1547) | (n = 238) | (n = 510) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female, % (n) | 75.7% (1171) | 76.9% (183) | 80.6% (411) | χ2 (4) = 13.84 |

| Male, % (n) | 24.3% (376) | 22.7% (54) | 19.4% (99) | p = 0.008 |

| Diverse, % (n) | 0 | 0.4% (1) | 0 | |

| Age in years, M (SD) | 51.67 (9.69) | 50.97 (9.88) | 53.03 (9.94) | F(2;95.37) = 4.87; p = 0.008 |

| Years in the profession, M (SD) * | 11.19 (9.20) | 12.10 (9.70) | 12.40 (9.90) | F(2;88.60) = 3.59; p = 0.028 |

| Orientation | ||||

| Psychodynamic, % (n) | 20.9% (324) | 16.4% (39) | 20.8% (106) | χ2 (8) = 15.74; |

| Humanistic, % (n) | 46.3% (716) | 50.8% (121) | 46.9% (239) | p = 0.046 |

| Systemic, % (n) | 22.0% (340) | 20.2% (48) | 22.7% (116) | |

| Behavioral, % (n) | 9.8% (151) | 8.8% (21) | 8.2% (42) | |

| Others, % (n) | 1.0% (16) | 3.8% (9) | 1.4% (7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winter, S.; Jesser, A.; Probst, T.; Schaffler, Y.; Kisler, I.-M.; Haid, B.; Pieh, C.; Humer, E. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affects the Provision of Psychotherapy: Results from Three Online Surveys on Austrian Psychotherapists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031961

Winter S, Jesser A, Probst T, Schaffler Y, Kisler I-M, Haid B, Pieh C, Humer E. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affects the Provision of Psychotherapy: Results from Three Online Surveys on Austrian Psychotherapists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):1961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031961

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinter, Stefanie, Andrea Jesser, Thomas Probst, Yvonne Schaffler, Ida-Maria Kisler, Barbara Haid, Christoph Pieh, and Elke Humer. 2023. "How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affects the Provision of Psychotherapy: Results from Three Online Surveys on Austrian Psychotherapists" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 1961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031961

APA StyleWinter, S., Jesser, A., Probst, T., Schaffler, Y., Kisler, I.-M., Haid, B., Pieh, C., & Humer, E. (2023). How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affects the Provision of Psychotherapy: Results from Three Online Surveys on Austrian Psychotherapists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031961