Abstract

Background: Psychological well-being (PWB) is a significant indicator of positive psychology. Thus far, the predictors of PWB are not well-understood among university students in Asian countries. Purpose: This study aimed to investigate the relationships between PWB and its predictors (stress, resilience, mindfulness, self-efficacy, and social support) in Thai and Singaporean undergraduates. Stress is perceived to have a negative influence on PWB, but mindfulness, resilience, self-efficacy, and social support indicate positive influences. Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive predictive research design was used with 966 Thai and 696 Singaporean university students. After calculating an adequate sample size and performing convenience sampling, we administered the following six standard scales: the Perceived Stress Scale, the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, the Mindfulness Awareness Scale, the General Self-Efficacy Scale, the Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and the Psychological Well-being Scale, along with a demographic questionnaire. Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and structural equation modeling were performed for participants’ PWB. Results: Mindfulness had significant effects on both factors of PWB, including autonomy and growth, and cognitive triad, across two samples. In the Thai sample, resilience most strongly predicted autonomy and growth and perceived stress did so the cognitive triad, whereas in the Singaporean sample, perceived control most strongly predicted autonomy and growth and support from friends did so the cognitive triad. Conclusion: These findings provide specific knowledge towards enhancing psychosocial interventions and promoting PWB to strengthen mindfulness, resilience, perceived control of stress, and social support.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of mental health problems among university students is alarming, with depression (76%), anxiety (88.4%), stress (84.4%), and other mental disorders (45.5 %) [1,2,3] dominating. Such problems have an impact on students’ psychological well-being (PWB) [4]. While pursuing education in colleges, university students in Asian countries commonly experience academic stress that may also affect their PWB [5]. Students in Thailand feel under substantial pressure from their parents and teachers to demonstrate good performance in university and achieve excellent grades [6]. Among university students, academic pressure is higher because of high workload, insufficient support from faculty members, and an unsupportive university climate [6,7]. Furthermore, academic excellence plays a significant role in determining students’ career success; therefore, some university students feel more stress and experience mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, substance abuse, aggression, sleep problems, suicidal ideation, and other behavioral problems [6,8,9,10]. Assessing university students’ PWB or mental health is an important task for mental health professionals.

PWB is a significant indicator of positive psychology. PWB has been defined in two different ways: (a) subjective well-being (happiness, positive affect, and life satisfaction) [11] and (b) eudaemonic well-being, including autonomy, self-acceptance, purpose in life, personal growth, positive relations with others, and environmental mastery [12,13]. Prior to establishing prevention interventions, one must fully understand the relationships between PWB and related variables. Evidence has revealed that PWB is negatively correlated with depression [14,15] Furthermore, several studies have suggested that PWB is related to perceived stress, resilience, mindfulness, perceived self-efficacy, and social support among university students [10,16,17,18]. However, most of these studies were conducted in Western countries and emphasized negative variables (such as stress) rather than positive aspects (such as resilience and self-efficacy). According to the positive psychology domain, disease prevention, mental health promotion, positive emotions, and optimal functioning are tantamount to pathology, dysfunction, and treatments [19]. Therefore, exploring both positive and negative variables is essential.

Stress is conceptualized as a relationship between individuals and their environment, occurring when persons appraise a situation as a threat exceeding their available coping resources [20]. Stress is found to be an important variable influencing psychological problems [10,21,22] and PWB [23,24]. Among medical students, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) indicated that stress management and resilience training significantly improved resilience, perceived stress, anxiety, and quality of life at eight weeks post-intervention [24].

Self-efficacy is defined as individuals’ beliefs in their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance that exercise influence over events that affect their lives [25]. During the transition to higher education, university students might experience feelings of vulnerability and lack of control over their academic lives, affecting their self-efficacy. Nevertheless, studies have revealed that self-efficacy is positively related to PWB (the absence of psychological problems) [23,26,27]. Another study found that self-efficacy and resilience lead to academic success (an indicator of well-being) among baccalaureate nursing students [26].

Resilience refers to individuals’ ability to change and deal with stressful events and adversity [28]. It reflects positive environmental adaptation despite risky situations and difficulties [29] that vary depending on individuals’ context, age, gender, time, and original culture [28]. Resilience is related to emotional problems such as anxiety, depression, hopelessness [10,30], and PWB [31,32,33]. One study examined the predicting effect on resilience, stress, mindfulness, and self-efficacy in PWB among Australian undergraduate nursing students. It found resilience to be the strongest predictor [33].

Mindfulness, also called “cautious attention”, refers to individuals’ ability to self-regulate attention to the present moment and to orientate toward acceptance, openness, and curiosity [34]. Evidence indicates that mindfulness is a strong predictor of PWB [23,33,35,36]. A study on 76 experienced meditators suggested that practicing mindfulness was significantly correlated with psychological well-being [35].

Social support, an external protective factor, is defined as individuals’ perception of adequate and valuable support influencing adjustment [37]. Social support can be received from significant others, family members, friends, and teachers [38]. Studies have demonstrated social support as being significantly associated with PWB [23,32,39]. In the Philippines, Klainin-Yobas et al. [23] examined PWB’s predicting factors among university students and found that social support from family and friends significantly predicted positive individual PWB.

The Current Study

Although previous studies have examined factors influencing PWB among undergraduate students [23,33], little is known about the magnitude of the relationships among those predicting factors. In addition, only a few studies have explored cross-cultural differences in PWB predictors, particularly in Asian countries. Therefore, this study examined associations among stress, self-efficacy, resilience, mindfulness, social support, and PWB in Thai and Singaporean undergraduates. The research questions are: (a) What are the patterns of relationships between stress, self-efficacy, resilience, mindfulness, social support, and PWB among undergraduate university students in Thailand? (b) What are the similarities and differences in the patterns of relationships between Thai and Singaporean samples?

This study was conducted at two government-supported universities in Thailand and Singapore. The rationales for using the two universities are outlined here. First, they are the top universities in each country, with high standards of learning environments, curriculums, faculty members, and various schools/faculties (such as Medicine, Science, Law, Art and Engineering). Second, students in both universities face high competition, and they must maintain high academic performance, possibly leading to academic stress. Third, both universities are located in a big city with a high cost of living. Students may experience additional stress concerning daily living (such as financial burden, traffic jams, among others). Finally, both universities provide mental health services, and our findings can be helpful to improve such services for students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

To answer the research questions, this study used a cross-sectional descriptive predictive research design, which allowed us to examine the phenomena of interest in natural settings [40].

2.2. Participants and Setting

The target populations were Thai and Singaporean undergraduate university students, regardless of faculty/school, academic year, or sociological background. Potential participants were excluded if they were diagnosed with medical and mental illnesses by physicians and/or psychiatrists. Convenience sampling was employed to recruit potential participants from all faculties, categorized into six groups: (1) Environment and Natural Resources; (2) Linguistics, Culture, and Education; (3) Medical Science; (4) Public Health; (5) Science and Technology; and (6) Social Science, Humanities, and Liberal Arts.

A sample size was determined through online power analyses for structural equation modeling [41]. An effect size of 0.88 was calculated according to findings from a previous study investigating stress, self-efficacy, and PWB among nursing students [42]. Using the effect size of 0.88, with the number of latent variables = 6, the number of observed variables = 8, power = 80%, and significance level = 0.05; an appropriate sample size for this study was determined to be at least 589 participants [41].

2.3. Recruitment Procedure

In Thailand, the researchers initially contacted a dean of each faculty to ask permission to collect data in their respective faculties. Afterwards, we organized meetings with undergraduate students in each faculty to explain the study and request their participation. Interested students were asked to sign the consent form and complete the self-reported paper-and-pencil questionnaire on the spot. Alternatively, students could contact the researchers later if they needed more time to consider. Approximately 1000 students attended the meeting, and 966 agreed to participate. Given that the questionnaires were anonymous, we were unable to identify reasons for non-participation.

In Singapore, the researchers sought permission from the president of the university to collect data from undergraduate students. Afterwards, the researchers sent an invitation e-mail to undergraduate students using the university e-mail list. The e-mail contained information about the study, the researchers’ contact information, and a link to an online questionnaire. Interested students were requested to click on the link, sign the online consent form and complete the questionnaire. Approximately 5000 students were approached via e-mail and 673 completed the online questionnaire anonymously. Given the anonymity, we did not know who did/did not participate, and thus, we were unable to identify reasons for non-participation.

2.4. Ethical Consideration

In Thailand, this study received ethical approval from the Human Rights Committee Related to Human Experimentation before commencing [COA. No. 2014/059.0805]. In Singapore, we received ethical approval from the University Institutional Review Board [NUS-IRB Reference Code: 12-385E]. All participants in Thailand and Singapore were asked to sign a written consent form prior to participating in the study.

2.5. Measures

We collected data through anonymous self-reported questionnaires, encompassing demographic information and the following instruments: the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale [28]; Perceived Stress Scale [43]; General Self-Efficacy Scale [44]; Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [45]; and Psychological Well-being Scale [12]. The demographic information included gender, age, nationality, religion, ethnic group, faculty and school, academic year, and annual family income.

In Thailand, we used the Thai-version, hard-copy, self-reported questionnaire, whereas the English-version and online questionnaires were administered in Singapore. There are two reasons for using different questionnaire formats. First, in Singapore, the university e-mail list of potential participants could be accessed by the researchers, who were also the university teachers. However, such an e-mail list was not accessible by the researchers in Thailand, and a face-to-face platform was required to meet the students. Second, Singaporean students were familiar with e-mail invitations and the online questionnaire, whereas Thai students were accustomed to hard copies. Furthermore, the response rate would have been very low if we had used the online version in Thailand.

2.6. Perceived Stress

The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS: [43]) was used to measure the degree of individuals’ thoughts and feelings about current events during the previous month. Each item was rated on a 5-item scale, 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The total score ranged from 0 to 40, with higher scores suggesting higher stress. Cronbach alphas were originally reported in the range of 0.84–0.86 among American graduate students [46]. With Thai adult participants, its test–retest reliability was 0.82 and the Cronbach alpha was 0.88 [47]. In this study, factor analyses revealed that PSS had two factors, perceived stress and perceived control, and the Cronbach alphas were 0.81 and 0.75 in Thailand, and 0.85 and 0.77 in Singapore.

2.7. Self-Efficacy

The Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES: [44]) consists of 10 items, which are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (exactly true). The Cronbach alphas of the GSES were originally reported in the range of 0.76–0.90 in adults and adolescents [44]. For the Thai version, the value was 0.84, suggesting good internal consistency [48]. In this study, GSES contained one factor. The Cronbach alphas in the Thai and Singaporean samples were 0.86 and 0.89, respectively.

2.8. Resilience

The 10-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale [49] was used to assess resilience by rating items on a 5-point scale from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true all the time). Total scores vary from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher resilience levels. Cronbach’s alpha was originally reported as 0.95 among American undergraduates [49]. Using the back-translation method, we translated and validated the Thai CD-RISC version. In this study, a factor analysis indicated that CD-RISC encompassed one structure, and the Cronbach alpha values of Thai and Singaporean university students were 0.86 [50] and 0.89, respectively, signifying good reliability.

2.9. Mindfulness

Mindfulness was measured by the 15-item Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) [51], using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). Total scores range from 15 to 90, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of mindfulness. MAAS is psychometrically sound, given its good range of internal consistency across several samples (œ = 0.80–0.87) and excellent test–retest reliability over a 1-month period (r = 0.81) [51]. The Thai version of MAAS was validated with 385 Thai college students, and the results from a confirmatory factor analysis suggested a single-factor structure and the scale’s validity [52]. This study showed that MAAS had one factor for both samples, and the Cronbach alpha values were 0.88 and 0.97, respectively, indicating good reliability.

2.10. Social Support

The 12-item Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; [43]) was used to assess an individual’s perceived social support by rating items on a 7-point scale, from very strongly disagree (1) to very strongly agree (7). It entails three factors of support—friends, family, and significant others. Total scores range from 1 to 84, with higher scores signifying greater perceived social support. The MSPSS was originally tested on American university students, and the Cronbach alphas were in the range of 0.84–0.92 for total scores, 0.81–0.98 for the “family” subscale, 0.90–0.94 for the “friends” subscale, and 0.83–0.98 for the “significant others” subscale [45]. In 2005, Boonyamalik translated the Thai version of MSPSS with the back-translation method. It showed good reliability, with the Cronbach alpha in the range of 0.88–0.89 [53,54]. This study’s internal consistency regarding the two samples’ three factors was as follows: Cronbach’s alphas for social support from friends = 0.88; family = 0.90; and significant others = 0.91 for Thai university students. Those for Singaporean university students were 0.89, 0.92, and 0.86, respectively.

2.11. Psychological Well-Being

The 18-item Psychological Well-being Scale (PWBS) [12] was used to assess university students’ psychological well-being on a 6-point scale from (1) strongly disagree to (6) strongly agree. Possible scores range from 18–108, with higher scores signifying better Cronbach alphas that were originally reported in the range of 0.87–0.93, suggesting good reliability [12]. The researchers translated this measurement into Thai using the back-translation method. For Thai university students, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80. In addition, the current study’s factor analyses revealed that PWB encompassed two factors: autonomy and growth, and the negative triad. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.85 and 0.70, respectively, in Thai; 0.85 and 0.56, respectively, in Singaporean university students [55].

2.12. Data Analysis

The data analysis was performed in two phases using IBM SPSS Statistics version 18.0. The first phase involved entering the data and checking entry accuracy. In Thailand, one researcher manually entered the questionnaire items to SPSS, while another researcher double-checked the entered data against the corresponding questionnaires. In Singapore, online questionnaires were digitally transferred to SPSS software. Next, the data cleaning began for both Thai and Singapore data sets by running the frequency of each study variable to ascertain that there were no out-of-range values. Where applicable, cross-tabulation (a feature in SPSS) was operated to confirm skip-and-fill questions were entered correctly. Descriptive statistics (i.e., frequency, mean, standard deviation, and graphical displays) was carried out to describe participants’ characteristics and study variables. The psychometric properties of all measurements were tested by a factor analysis and internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha).

The second phase tested the predictors of PWB via structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS software. Specifically, PWB factors (autonomy and growth, and negative triad) [56] were submitted to AMOS as dependent variables. Predictors included perceived stress, perceived control, mindfulness, resilience, and social support (support from friends, support from family, and support from significant others). The strength of the predictor would be determined by a standardized regression coefficient (β), and statistical significance was set as α = 0.05. An overall fit of the SEM model was determined by (a) confirmatory fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and incremental fit index (IFT) > 0.90; and (b) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 [57].

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information and Study Variables

For the Thai sample, 966 students responded using the paper-and-pencil questionnaires. The average age was 20.21 (SD = 1.51), with females (67.30%, n = 650), males (31.80%, n = 307), and missing data (0.90%, n = 9). Most Thai students were Buddhist (94.50%, n = 913), followed by Christian (2.10%, n = 20), and Islamic (1.30%, n = 13) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic of sample.

For the Singaporean sample, 696 students completed the online questionnaires. The average age was 22.39 (SD = 5.18), with females (59.10%, n = 411), males (27.70%, n = 193), and missing data (13.20%, n = 92). Most were Christian (24.70%, n = 172), followed by Buddhist (18.20%, n = 127), Islamic (7.90%, n = 55), and others (49.20%, n = 342).

For both Thai and Singaporean students, all study variables—perceived stress, perceived control, resilience, self-efficacy, and mindfulness; all support the variables autonomy and growth, as well as negative triad—display approximately normal distribution (Table 2 and Table 3, respectively).

Table 2.

Description of study variables for Thai sample (n = 966).

Table 3.

Description of study variables for Singaporean sample (n = 673).

3.2. Predictors of Psychological Well-Being

3.2.1. Thai Sample

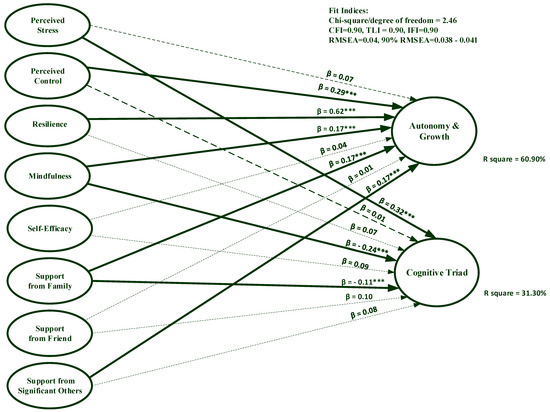

Figure 1 displays predictors of PWB among Thai youths, with solid lines representing predictors achieving statistical significance and broken lines representing insignificant regression paths. The findings suggested that the hypothesized model had an adequate fit to the data, evidenced by Chi-square per degree of freedom (χ2/df) = 2.46, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, IFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.04, 90% confidence interval of RMSEA = 0.038, 0.041. Furthermore, resilience (β = 0.62, p < 0.001), perceived control (β = 0.29, p < 0.001), mindfulness (β = 0.17, p < 0.001), support from significant others (β = 0.17, p < 0.001), and support from family (β = 0.17, p < 0.001) significantly predicted the PWB autonomy and growth factor, with 60.90% of variance explained by all independent variables. Additionally, mindfulness (β = −0.24, p < 0.001), perceived stress (β = 0.32, p < 0.001), and support from family (β = 0.11, p = 0.03) significantly predicted the cognitive triad factor of PWB, with all independent variables explaining 31.30% of variance.

Figure 1.

Predictors of psychological well-being among university students in Thailand. *** Significant at 0.001.

3.2.2. Singaporean Sample

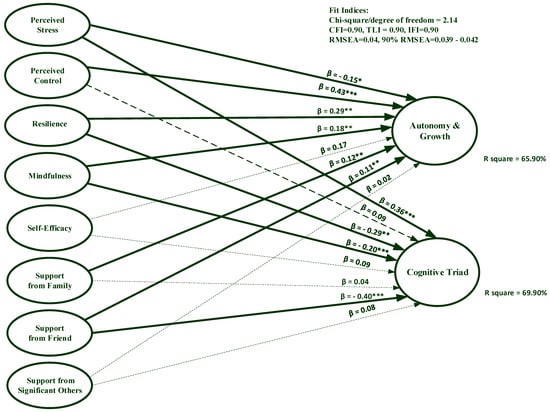

Figure 2 suggests that the hypothesized model displayed an acceptable fit, as evidenced by χ2/df = 2.14, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, IFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.04, and the 90% confidence interval of RMSEA = 0.039,.042. Note that these fit indices are comparable with those in the Thai sample. Furthermore, the autonomy and growth factor of PWB was significantly predicted by resilience (β = 0.29, p = 0.005), perceived stress (β = −0.15, p = 0.02), perceived control (β = 0.43, p < 0.001), mindfulness (β = 0.18, p < 0.001), support from friends (β = 0.11, p = 0.004), and support from family (β = 0.12, p = 0.001).

Figure 2.

Predictors of psychological well-being among university students in Singapore. * Significant at 0.05, ** significant at 0.01, *** significant at 0.001.

The cognitive triad factor was significantly predicted by resilience (β = −0.29, p = 0.006), perceived stress (β = 0.36, p < 0.001), mindfulness (β = −0.20, p < 0.001), and support from friends (β = −0.40, p < 0.001). All independent variables explained 65.90% and 69.90% of variance on the autonomy and growth, and the cognitive triad, respectively.

Altogether, the findings from both the Thai and Singapore samples demonstrated that mindfulness had significant effects on PWB factors. In the Thai sample, resilience most strongly predicted the autonomy and growth factor, while perceived stress most strongly predicted the cognitive triad factor. In the Singaporean sample, perceived control and support from friends most strongly predicted the autonomy and growth factor, and the cognitive triad factor.

4. Discussion

This study’s results demonstrated that Thai and Singaporean university students had a medium level of the autonomy and growth factor and negative triad factor of PWB. Negative triad reflects individuals’ negative perceptions toward self, other people, and their future [56]. Such perceptions included disappointing achievements, difficulty making and maintaining relationships with others, and little purpose in life. In the following variables, these students’ PWB models differed slightly: perceived stress, perceived control, resilience, social support from family, friends, and significant others. Other variables were similar, specifically mindfulness and self-efficacy.

In this study, stress was separated into two components: perceived stress and perceived control. In the Thai sample, perceived stress correlated negatively with the negative triad PWB factor, while the relationship between perceived control and the autonomy and growth of PWB was positive. In another study, individuals who perceived their stress as threatening or harmful indicated their potential to cause damage, thus provoking negative emotions. If they perceived stress as challenges that they could control with sufficient coping resources, they understood the potential rewards and ability to experience positive emotions [57]. Thai university students who perceived their stress as a life-threatening situation or as stressful life events might manifest the negative triad of PWB. In contrast, university students who interpreted their stressful life events positively and believed in their ability to control stress had greater autonomy and PWB growth.

However, the finding of perceived control revealed that university students could handle stress effectively and that individuals with effective coping strategies might have greater PWB, in congruence with the literature [58,59]. In comparison with Singaporean university students, the PWB model showed perceived stress as not only significantly negatively correlated with the autonomy and growth PWB, but also as significantly positively correlated with the cognitive triad PWB. Simultaneously, the relationships between perceived control and both PWB components were similar in the Thai sample. A previous study also supported that perceived stress had a negative correlation with positive PWB and a positive correlation with negative PWB [33]. Hence, promoting an intervention program of PWB in each sample should be considered its difference.

Mindfulness significantly predicted PWB among both samples, congruent with previous studies [23,33,60,61]. In addition, studies have suggested that mindfulness can reduce negative emotions: depression, rumination, stress, anxiety, somatization, aggression, and avoidance behavior [61]. Indeed, all previous studies indicated that mindfulness might reduce negative emotions and, correspondingly, increase PWB. Consistent with this study’s result showing a higher level of mindfulness, university students tended to mention higher autonomy and PWB growth and a lower negative triad PWB factor. This tendency is congruent with the literature describing “mindfulness”—conceptualized as promoting individuals’ well-being—as awareness of the present moment and non-judgment [50]. Individuals with elevated mindfulness are aware of their surroundings, thoughts, and feelings, without fixating or labeling things as good or bad [50]. Instead, they extend attitudes of curiosity, patience, and non-judgment towards distress because they better attend to the present, reduce rumination, have a greater ability to control their emotions and behaviors, and use more and better adaptive coping and management techniques to deal with undesirable stressors. All of these lead to greater PWB [62,63,64]. Importantly, these findings revealed that cultural differences between Thai and Singaporean students did not influence mindfulness in promoting PWB.

Resilience most strongly predicted the autonomy and growth PWB in the Thai sample and in both components of PWB in the Singaporean sample. Similarly, university students in Australia who possessed greater resilience reported higher levels of PWB [33]. It is possible that highly resilient individuals could better recover from adverse events and adjust to stressful situations [29,65]; resilience buffers them from the stress of life events, so they perceive stress as a challenge that helps them develop environmental mastery, positive relationships, growth, and self-determination [66]. Resilient university students could reappraise negative experiences as positive episodes [67], thus reducing the risk of maladaptive outcomes [68]. Resilient Thai university students could effectively develop their autonomy and growth to deal with stress, while Singaporean university students could develop both PWB components. Therefore, among university students, resilience seems well established in the literature as links to PWB.

In both study samples, self-efficacy had no significant effects on PWB, even though it might be enhanced by accomplishment, and well-being might be enhanced by beliefs about capabilities [69]. These findings were incongruent with a previous study [23]. Following previous studies [23,33,70], support by family, friends, and significant others related meaningfully to PWB, indicating that social support could enhance a person’s ability to handle stress effectively and promote PWB [71]. Thai university students could apply perceived support from family and significant others to their autonomy and growth PWB and to the reduction in the PWB negative triad. Family social support essentially contributed to PWB in Thai university students because although some had moved away to study, family connectedness was still profound.

According to the self-determination theory (SDT), adolescents perceiving their parents as a supportive resource could develop their autonomy, including their natural desire to experience a sense of personal decision making, volition, and psychological freedom [72]. For Singaporean students, support from friends contributed to both PWB components, while support from family only promoted PWB autonomy and growth. Especially because of the competitive, international environment at the Singaporean university, perceived support from friends influenced PWB, and this result corresponded with a previous study of Filipino university students [23]. These findings support cultural differences between Thai and Singaporean students as influences in their daily living.

Finally, the findings showed slight differences between Thai and Singaporean students because of diverse cultural and academic environments. For instance, most university students in Singapore had come from foreign countries and manifested a wide range of skills and abilities; thus, international competition and high education qualifications became inherently tense for them. Moreover, Singapore’s average cost of living is quite high and leads university students to strive diligently for the highest-paying careers and to become financially independent.

Like most studies, this one had some limitations. First, the cross-sectional research had limited time to provide a deep understanding of individuals’ PWB development. Therefore, longitudinal research is needed in future studies. Second, both hard-copy and online self-reported questionnaires are considered subjective data and might be subject to social desirability. For a more accurate reflection of PWB, longitudinal research should be implemented. Third, the use of different formats of questionnaires might minimize the comparability of findings across the two samples. Finally, the use of convenient sampling might limit the generalizability of the research findings. Nevertheless, a large sample size in the two samples might minimize this issue.

The study’s results further suggested several important factors for recommendations. To improve university students’ PWB, implementing intervention programs—for example, mindfulness-based stress-reduction programs, resilience programs, and social support programs as part of university policy—would promote PWB and help prevent students’ mental health problems. Of course, the effectiveness of such intervention programs—concentrating on mindfulness, resilience, perceived control of stress, and social support—should be carefully and regularly evaluated.

5. Conclusions

This study compared predictors of PWB across the two samples. Both the Thai and Singaporean samples’ mindfulness had significant effects for both PWB factors. In the Thai sample, resilience most strongly predicted the autonomy and growth PWB, and perceived stress did so the cognitive triad PWB. In the Singaporean sample, perceived control most strongly predicted the autonomy and growth PWB, and support from friends did so the cognitive triad PWB. Future research should test this hypothesized model in other university samples and implement effective intervention programs to enhance PWB in undergraduate university students.

Author Contributions

W.T. and P.K.-Y. planned the study and drafted the manuscript. N.V. and P.K.-Y. planned study, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. N.V., W.T., Y.S. and P.K.-Y. recruited the participants and performed data collection. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “China Medical Broad, Faculty of Nursing, Mahidol University”. And the APC was funded by Mahidol University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. It received approval and ethical clearance from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Mahidol University, Thailand (COA. No. IRB-NS2014/059.0805) before data collection. All procedures were conducted according to the IRB guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study. A statement concerning ethics approval is included in this manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions from Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Mahidol University, Thailand.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the China Medical Broad, Faculty of Nursing, Mahidol University, for the research funding required to successfully meet our goal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Asif, S.; Mudassar, A.; Shahzad, T.Z.; Raouf, M.; Pervaiz, T. Frequency of depression, anxiety and stress among university students. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S.K.; Lattie, E.G.; Eisenberg, D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by US college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P.; et al. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, C.K.; Ngo, C.W.; Binti Zulkifli, R.A.; Vellasamy, R.; Suresh, K. Depression, anxiety and stress among undergraduate students: A cross sectional study. Open J. Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.B.; Yates, S. Academic Expectations as Sources of Stress in Asian Students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2011, 14, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanoi, W.; Pornchaikate Au-Yeong, A.; Ondee, P. Factors affecting the mental health of the faculty of nursing students, Mahidol University. Thai. J. Nurs. Counc. 2012, 27, 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Porru, F.; Schuring, M.; Bultmann, U.; Portoghese, I.; Busdorf, A.; Robroek, S.J.N. Associations of university student life challenges with mental health and self-rated health: A longitudinal study with 6 months follow-up. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 296, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, R.P.; Huan, V.S. Relationship between Academic Stress and Suicidal Ideation: Testing for Depression as a Mediator Using Multiple Regression. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2006, 37, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraag, G.; Zeegers, M.P.; Kok, G.; Hosman, C.; Abu-Saad, H.H. School Programs Targeting Stress Management in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 44, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.; Roberts, C.R.; Xing, Y. Restricted Sleep among Adolescents: Prevalence, Incidence, Persistence, and Associated Factors. Behav. Sleep Med. 2011, 9, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudemonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, A.; Friede, T.; Putz, R.; Ashdown, J.; Martin, S.; Blake, A.; Adi, Y.; Parkinson, J.; Flynn, P.; Platt, S.; et al. Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): Validated for Teenage School Students in England and Scotland. A Mixed Methods Assessment. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadow, C.; Houghton, S.; Hunter, S.C.; Rosenberg, M.; Wood, L. Associations between Positive Mental Well-Being and Depressive Symptoms in Australian Adolescents. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 34, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoormans, D.; Nyklíček, I. Mindfulness and Psychological Well-Being: Are They Related to Type of Meditation Technique Practiced? J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2011, 17, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; DeCourville, N.; Sadava, S. Positive Affect, Negative Affect, Stress, and Social Support as Mediators of the Forgiveness-Health Relationship. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 152, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, X.; Miao, Y.; Xu, Y. Negative Life Events and Mental Health of Chinese Medical Students: The Effect of Resilience, Personality and Social Support. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 196, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobau, R.; Seligman, M.E.; Peterson, C.; Diener, E.; Zack, M.M.; Chapman, D.; Thompson, W. Mental Health Promotion in Public Health: Perspectives and Strategies from Positive Psychology. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Murberg, T.A.; Bru, E. School-Related Stress and Psychosomatic Symptoms among Norwegian Adolescents. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2004, 25, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konick, L.C.; Gutierrez, P.M. Testing a Model of Suicide Ideation in College Students. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2005, 35, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klainin-Yobas, P.; Ramirez, D.; Fernandez, Z.; Sarmiento, J.; Thanoi, W.; Ignacio, J.; Lau, Y. Examining the Predicting Effect of Mindfulness on Psychological Well-Being among Undergraduate Students: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 91, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Facilitating and Hindering Motivation, Learning, and Well-Being in Schools: Research and Observations from Self-Determination Theory. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Wentzel, K.R., Miele, D.B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 96–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Mental Health; Friedman, H., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994; Reprinted in Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Ramachaudran, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 4, pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, H.; Reyes, H. Self-Efficacy and Resilience in Baccalaureate Nursing Students. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2012, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priesack, A.; Alcock, J. Well-Being and Self-Efficacy in a Sample of Undergraduate Nurse Students: A Small Survey Study. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e16–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary Magic: Resilience Processes in Development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangon, S.; Nintachan, P.; Kingkaew, J. Factors predicting resilience in nursing students. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health 2018, 32, 150–158. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Souri, H.; Hasanirad, T. Relationship between Resilience, Optimism and Psychological Well-Being in Students of Medicine. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 1541–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkoc, A.; Yalcin, I. Relationships among Resilience, Social Support, Coping, and Psychological Well-Being among University Students. Turk. Psychol. Couns. Guid. J. 2015, 5, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.X.; Turnbull, B.; Kirshbaum, M.N.; Phillips, B.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Assessing Stress, Protective Factors and Psychological Well-Being among Undergraduate Nursing Students. Nurse. Educ. Today 2018, 68, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go There You Are; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenström, F. Studying Mindfulness in Experienced Meditators: A Quasi-Experimental Approach. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, H.; Biswas, A.G.; Soohinda, G.; Dutta, S. Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being among Medical College Students. Open J. Psychiatry Allied Sci. 2019, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asberg, K.K.; Bowers, C.; Renk, K.; McKinney, C. A Structural Equation Modeling Approach to the Study of Stress and Psychological Adjustment in Emerging Adults. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2008, 39, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaux, A.; Phillips, J.; Holly, L.; Thomson, B.; Williams, D.; Stewart, D. The Social Support Appraisals (SS-A) Scale: Studies of Reliability and Validity. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1986, 14, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, S.; Watson, J.; Partridge, H. Conceptualising Social Media Support for Tacit Knowledge Sharing: Physicians’ Perspectives and Experiences. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, N.; Grove, S. The Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisal, Synthesis and Generation of Evidence, 6th ed.; Saunders Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, D.S. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models (Online Software). 2012. Available online: http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc3 (accessed on 6 June 2014).

- Gibbons, C.; Dempster, M.; Moutray, M. Stress, Coping and Satisfaction in Nursing Students. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 621–632. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. Perceived Stress Scale. Meas. Stress A Guide Health Soc. Sci. 1994, 10, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric Characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar]

- Sood, A.; Prasad, K.; Schroeder, D.; Varkey, P. Stress Management and Resilience Training among Department of Medicine Faculty: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 858–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. The Thai Version of the PSS-10: An Investigation of Its Psychometric Properties. BioPsychoSocial. Med. 2010, 12, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmak, V.; Sirisunthorn, A.; Meena, P. Validity of the General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale. J. Psychiatr. Assoc. Thail. 2001, 47, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Stein, M.B. Psychometric Analysis and Refinement of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-Item Measure of Resilience. J. Trauma. Stress 2007, 20, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vongsirimas, N.; Thanoi, W.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Evaluating Psychometric Properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (10-Item CD-RISC) among University Students in Thailand. J. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 35, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christopher, M.S.; Charoensuk, S.; Gilbert, B.D.; Neary, T.J.; Pearce, K.L. Mindfulness in Thailand and the United States: A Case of Apples versus Orange? J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 590–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonyamalik, P. Epidemiology of Adolescent Suicidal Ideation: Roles of Perceived Life, Stress, Depressive Symptoms, and Substance Use. Ph.D. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005; p. 422. [Google Scholar]

- Vongsirimas, N.; Sitthimongkol, Y.; Beeber, L.S.; Wiratchai, N.; Sangon, S. Relationship among Maternal Depressive Symptoms, Gender Differences and Depressive Symptoms in Thai Adolescents. Thai J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 13, 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Vongsirimas, N.; Phetrasuwan, S.; Thanoi, W.; Yobas, P.K. Psychometric Properties of the Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support among Thai Youth. Thai Pharm. Health Sci. J. 2018, 36, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Klainin-Yobas, P.; Thanoi, W.; Vongsirimas, N.; Lau, Y. Evaluating the English and Thai-Versions of the Psychological Well-Being Scale across Four Samples. Psychology 2020, 11, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cicognani, E. Coping Strategies with Minor Stressors in Adolescence: Relationships with Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Psychological Well-Being. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagone, E.; Elvira De Caroli, M.E. A Correlational Study on Dispositional Resilience, Psychological Well-Being, and Coping Strategies in University Students. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 2, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongsirimas, N.; Sitthimongkol, Y.; Kaesornsamut, P.; Thanoi, W.; Pumpuang, W.; Phetrasuwan, S.; Kasornsri, S.; Thavorn, T.; Pianchob, S.; Pimroon, S.; et al. Mediating Role of Mindfulness, Self-Efficacy, and Resilience on the Stress- Psychological Well-Being in Thai Adolescent. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 5375–5391. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Fang, S. Adolescents’ Mindfulness and Psychological Distress: Mediating role of Emotional Regulation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.; Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. A Multi-Method Examination of the Effects of Mindfulness on Stress Attribution, Coping, and Emotional Well-Being. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anicha, C.L.; Ode, S.; Moeller, S.K.; Robinson, M.D. Toward a Cognitive View of Trait Mindfulness: Distinct Cognitive Skills Pre-Dict Its Observing and Nonreactivity Facets. J. Pers. 2012, 80, 255–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Salili, F.; Ho, S.Y.; Mak, K.H.; Lai, M.K.; Lam, T.H. The Perceptions of Adolescents, Parents, and Teachers on the Same Adolescent Health Issues. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2005, 26, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, M.M.; Mazmanian, D.; Oinonen, K.; Mushquash, C.J. Executive Function and Self-Regulation Mediate Dispositional Mindfulness and Well-Being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological Well-Being Revisited Advances in the Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Psychother. Psychosom. 2014, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Vythilingam, M.; Charney, D.S. The Psychobiology of Depression and Resilience to Stress: Implications for Prevention and Treatment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 255–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagone, E.; De Caroli, M.E.D. Relationships between Resilience, Self-Efficacy and Thinking Styles in Italian Middle Adolescents. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 92, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.M.; Weiss, A.; Shook, N.J. Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Savoring: Factors That Explain the Relation between Perceived Social Support and Well-Being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 152, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).