Usage of the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire: A Systematic Review of a Comprehensive Job Stress Questionnaire in Japan from 2003 to 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Previous Work

1.2. Background in Japan

1.3. Research Gaps and Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Data Collection Process

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

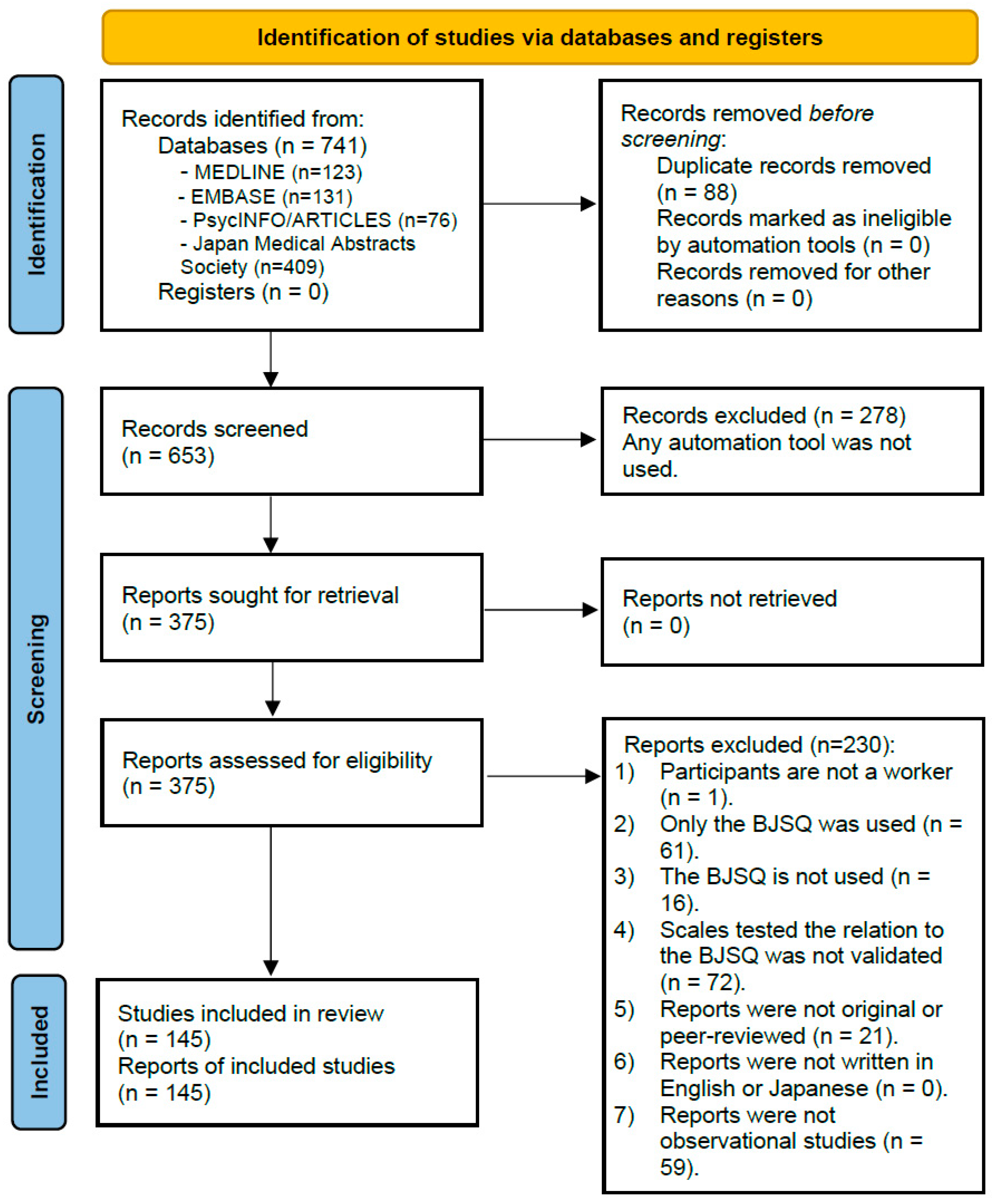

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

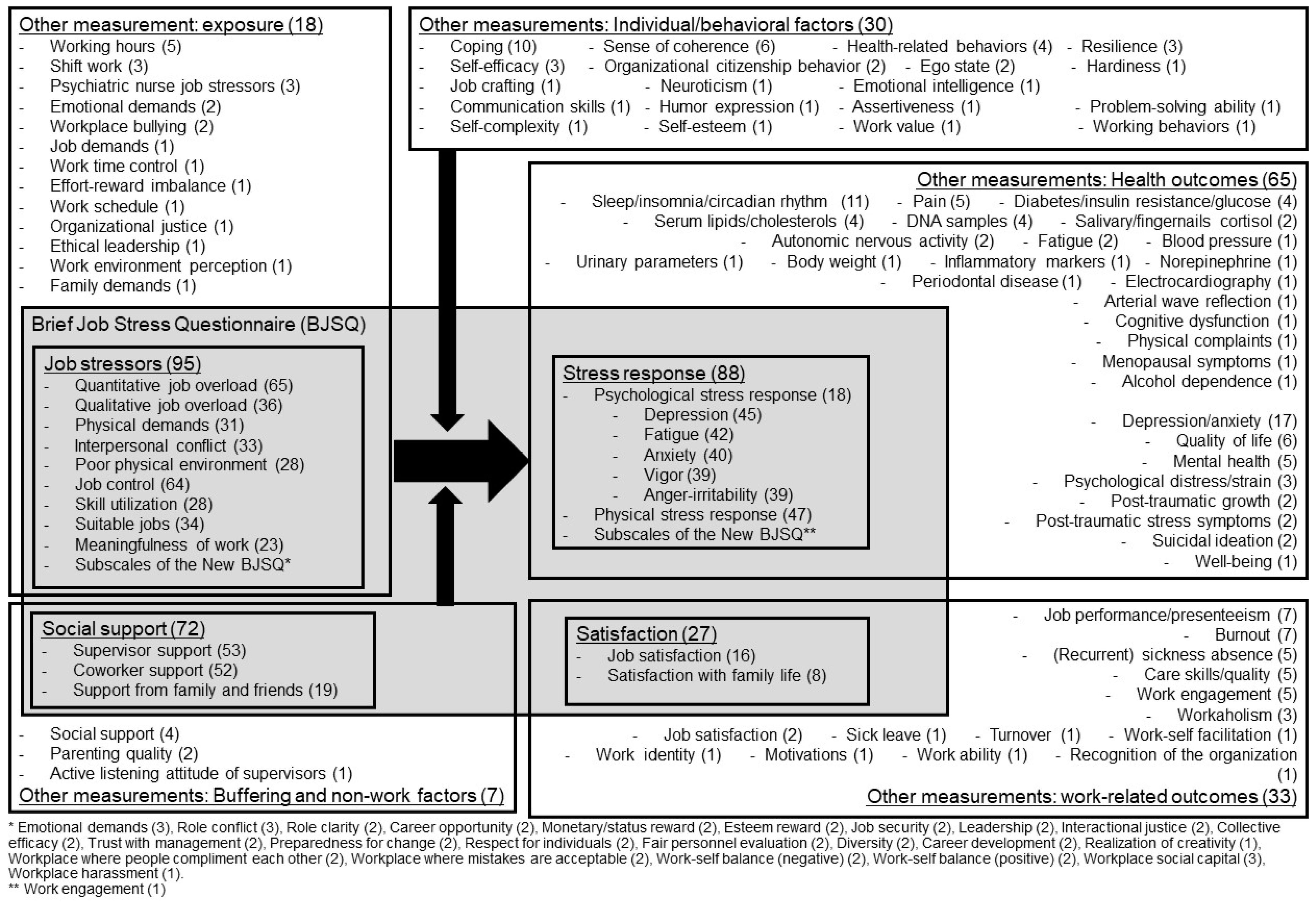

3.3. Used Subscales and Other Measurements

3.4. Scoring Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Author | Study Design | Recruitment | Sample | Subscale Used | Scoring | Other Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [23] | Sugito et al. (2021) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 6620 male company workers aged 40 years or older who underwent routine annual health checkups and a stress check | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Standardized scores were calculated on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest). | Development of diabetes mellitus (HbA1c by blood sampling or using antidiabetic drugs) |

| 2 [24] | Takahashi et al. (2020) | Longitudinal | Healthcare centers | 6326 male workers who received annual health checkups | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Participants were dichotomized into positive or negative; points 1 and 2 received a score of 0, and points 3 and 4 received a score of 1. An individual was considered positive for depression when they scored at least 1 in each of the depression-related items. | Development of type 2 diabetes (HbA1c by blood sampling or diabetes medication) |

| 3 [25] | Kachi et al. (2020) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 9657 workers at a financial service company | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Participants were categorized into high stress or not, as defined by the Stress Check Program in Japan. | Turnover (Human resource records) |

| 4 [26] | Shimazaki et al. (2020) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 635 workers of small- to medium-sized enterprises | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) | Continuous score | Mental health promotion behaviors (Mental Health Promotion Behavior scale, MHPB) |

| 5 [27] | Wang et al. (2020) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 307 full-time and white-collar employees in wide-ranging occupations | Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Ethical leadership (Ethical Leadership Scale) Mutual support (Self-developed, validated previously) |

| 6 [28] | Inoue et al. (2019) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 14,687 employees in a financial service company | Job satisfaction (1 item) | Participants who answered 1 or 2 were dichotomized into “dissatisfied” and those who answered 3 or 4 into “satisfied” groups. | Long-term sickness absence (Personnel records) |

| 7 [29] | Hino et al. (2019) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 922 workers in a manufacturing company in Japan | Depression (6 items) | Continuous score | Overtime work hours (Personnel records) |

| 8 [30] | Morimoto et al. (2019) | Longitudinal | Nursing or welfare facilities | 379 employed family caregivers of people with dementia | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (3 items) Emotional demands (1 item) Role conflict (1 item) | Continuous score | Psychological strain (Stress Response Scale, SRS) |

| 9 [31] | Ogawa et al. (2018) | Nested case-control study | Public sectors | 382 public servants in the Kinki area | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) Satisfaction with family life (1 item) | Continuous score | Long-term sickness absence due to mental disorders (Doctor’s medical certification) |

| 10 [32] | BJSQ et al. (2018) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 7356 male and 7362 female employees in a financial service company | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Participants were categorized into high stress or not, as defined by the Stress Check Program in Japan. | Sickness absence (Human resources records) |

| 11 [33] | Fukuda et al. (2018) | Longitudinal | Public sectors | 16,032 public servants in the Kinki area | Job stressors (17 items) Stress responses (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Continuous score | Long-term sickness absence due to mental disorders in the same work unit (Medical certification) |

| 12 [34] | Okita et al. (2017) | Longitudinal | Hospitals | 42 female novice nurses at Kagoshima University Hospital | Psychological stress response (18 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Physical examination parameters (Blood sampling) Urinary parameters (Urine sampling) One-year body weight change |

| 13 [35] | Hino et al. (2016) | Longitudinal | Healthcare centers | 1815 male workers who underwent health checkups at a healthcare center in the Kanto (east coast) region | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | A four-category variable for each psychosocial work characteristic was created (1) stable low, (2) increased, (3) decreased, and (4) stable high group. The demands/control ratio was also calculated. | Insulin resistance (Blood sampling) |

| 14 [36] | Sakuraya et al. (2016) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 929 employees from a thinktank company | Workplace social capital (3 items) | Respondents were grouped into tertiles (high, middle, and low). Further, respondents were categorized into tertiles based on the distribution of each item score. | Onset of major depressive episode (World Health Organization’s version of Composite International Diagnostic Interview 3.0, WHO-CIDI 3.0) |

| 15 [37] | Taniguchi et al. (2016) | Longitudinal | Nursing or welfare facilities | 543 workers at welfare facilities for the elderly. | Psychological stress response (18 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | The participants were dichotomized into high and low stress groups. For psychological stress response, >13 and >12 indicated a high score in men and women, respectively. For physical stress response, >4 or >5 indicated a high score in men or women, respectively. | Workplace bullying (Japanese version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire, NAQ) |

| 16 [38] | Watanabe et al. (2016) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 126 employees from 15 worksites | Psychological stress response (18 items) | Continuous score | Physical activity (Japanese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, IPAQ) |

| 17 [39] | Endo et al. (2015) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 540 employees from one of the biggest telecommunication companies | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) | Based on the means of “organizational job demands” or “organizational job control” scores, the departments were dichotomized into two groups (high/low). | Recurrent sickness absence due to depression (Psychiatric certification) |

| 18 [40] | Shimazu et al. (2015) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 1196 employees in an industrial machinery company | Psychological stress response (18 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) Satisfaction with family life (1 item) | Continuous score | Work engagement (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, UWES) Workaholism (Dutch Workaholism Scale, DUWAS) |

| 19 [41] | Matsudaira et al. (2014) | Longitudinal | Existing cohorts | 3811 workers from a prospective cohort of the “The Japan epidemiological research of Occupation-related Back pain (JOB)” study. | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) Satisfaction with family life (1 item) | For each factor, standardized scores were developed on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest) based on a sample of more than 10,000 Japanese workers. The five original responses were reclassified into “not feeling stressed,” where low, slightly low, and moderate were combined, and “feeling stressed,” where slightly high and high were combined. | Low back pain (Von Korff’s grading method) |

| 20 [42] | Wada et al. (2013) | Longitudinal | Web surveys | 1810 participants aged 20–70 years from a marketing survey | Stress responses (29 items) | The participants were divided into quartiles according to the total stress response score at baseline. | Sick leave due to depression (Medical certificates) |

| 21 [43] | Demerouti et al. (2013) | Longitudinal | Existing cohorts | 471 Japanese employees with young children from the Tokyo Work–family INterface (TWIN) study | Supervisor support (3 items) | Continuous score | Work–self facilitation (Four items based on the Survey Work–home Interference Nijmegen, SWING) |

| 22 [44] | Okuno et al. (2013) | Longitudinal | Hospitals | 105 nurses in from a hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Post-traumatic growth (Japanese version of Posttraumatic Growth Inventory, PTGI-J) |

| 23 [45] | Urakawa et al. (2012) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 299 employees in small enterprises | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Sense of coherence (Japanese version of Sense of Coherence Scale, SOC) |

| 24 [46] | Takahashi et al. (2012) | Longitudinal | Web surveys | 2382 daytime workers selected randomly from a market research panel | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor and coworker support (6 items) | Continuous score | Fatigue (An 11-item scale from the Checklist for Accumulated Fatigue due to Overwork) Depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies for Depression scale, CES-D) Work time control (A five-item scale from Takahashi et al. (2011)) Daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale) |

| 25 [47] | Sugimura and Thériault (2010) | Cross-sectional Longitudinal | Private companies | 1157 male employees in an information technology company | Supervisor support (3 items) | Cross-sectional survey: supervisor support score was categorized into four groups for every quartile score. Longitudinal survey: supervisor support scores of each survey period were dichotomized based on the median score to create four dual categories that take into account the changes in supervisor support between the survey periods (i.e., low [T1]–low [T2], low [T1]–high [T2], high [T1]–low [T2], and high [T1]–high [T2]). Continuous score | Work ability (Work Ability Index, WAI) |

| 26 [48] | Shimazu and de Jonge (2009) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 211 employees in a construction machinery company | Psychological stress response (18 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Effort–reward imbalance (Japanese version of Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire, ERI-Q) |

| 27 [49] | Shimazu et al. (2008) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 193 employees working in a construction machinery company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Psychological stress response (18 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Active coping (Brief Stress for Coping Scale, BSCP) |

| 28 [50] | Shimazu and Schaufeli (2007) | Longitudinal | Private companies | 488 male employees in a construction machinery company | Job stressors (17 items) Stress responses (29 items) | Continuous score | Coping (Brief Stress for Coping Scale, BSCP) Job performance (World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire, WHO-HPQ) |

| 29 [51] | Tsuboi et al. (2006) | Longitudinal | Hospitals | 33 female nurses working in Fujita Health University Hospital | Job stressors (17 items) | Those who scored more “1”s were placed in a high job stress group and those who scored more “5”s were placed in a low job stress group, according to the manual of the BJSQ. | Cholesterols Lipid peroxidation antioxidants in the plasma (Blood sampling) Depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies for Depression scale, CES-D) |

| 30 [52] | Hirokawa et al. (2022) (Epub was published in 2021) | Cross-sectional | Healthcare centers | 766 healthy workers enrolled in mental health checkups | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) | Continuous score | Salivary cortisol (Saliva sampling) |

| 31 [53] | Takaesu et al. (2021) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 4645 office workers from 29 companies | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Participants were categorized into high stress or not, defined by the Stress Check Program in Japan. | Sleep duration (Self-reported) |

| 32 [54] | Hidaka et al. (2021) | Cross-sectional | Web surveys | 1986 workers from the Internet survey | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Job strain was calculated by dividing quantitative job overload by job control. Social support was used in continuous score. | Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) |

| 33 [55] | Toyoshima et al. (2021) | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of faculty staff members or alumni of universities | 536 workers from the recruitment that performed through the word of mouth, using poster at the Tokyo Medical University | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Sleep reactivity (The Ford Insomnia Response to Stress Test, FIRST) Cognitive dysfunction (The Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment, COBRA) |

| 34 [56] | Adachi et al. (2021) | Cross-sectional | Healthcare centers | 2739 university workers who underwent an annual health checkup at the Health and Counseling Center, Osaka University | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Continuous score | Sleep duration (Self-reported) |

| 35 [57] | Hayashida et al. (2021) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 2905 workers from 17 offices at companies | Stress response (29 items) | Continuous score | Presenteeism (Work Limitations Questionnaire, WLQ) Sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) |

| 36 [58] | Ôga and Chiba (2021) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 765 nurses from eight hospitals that have 100 or more beds in Tohoku, Japan | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Humor expression (Humor Expression Scale) |

| 37 [59] | Adachi (2021) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 114 workers in a manufacturing company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Shift work (Self-reported) |

| 38 [60] | Ooka et al. (2021) | Cross-sectional | Healthcare centers | 69,805 workers in 117 companies that conducted the national Stress Check Program through Public Health Research Center | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Participants were categorized into high stress or not, as defined by the Stress Check Program in Japan. | Shift work (Self-reported) Overtime work hours (Self-reported) |

| 39 [61] | Terada and Nagamine (2020) | Cross-sectional | Public sectors | 326 male workers of the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) | Continuous score | Coping (Tri-Axial Coping Scale, TAC-24) Resilience (Japanese Short version of Resilience Competency Scale, RCS-JS) Hardiness (Validated scale) |

| 40 [62] | Sameshima et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of faculty staff members or alumni of universities | 528 nonclinical workers recruited by convenience sampling through our acquaintances at Tokyo Medical University | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) | Continuous score | Parenting quality (Parental Bonding Instrument) Resilience (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale) |

| 41 [63] | Shimura et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 5640 workers from 29 companies in Tokyo | Job stressors (17 items) Social support (9 items) | Continuous score | Sleep schedule (Self-reported) Sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) |

| 42 [64] | Furuichi et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 2899 workers from 17 companies in Tokyo, Japan | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Continuous score | Presenteeism (Work Limitation Questionnaire, WLQ) Sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) |

| 43 [65] | Miyama et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of faculty staff members or alumni of universities | 535 nonclinical workers recruited by convenience sampling through our acquaintances at Tokyo Medical University | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Diurnal type (Diurnal Type Scale, DTS) Sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI) |

| 44 [66] | Seki et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of faculty staff members or alumni of universities | 528 workers recruited by convenience sampling through our acquaintances at Tokyo Medical University | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) | Continuous score | Parenting quality (Parental Bonding Instrument) Neuroticism (Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised, EPQ-R) |

| 45 [67] | Kikuchi et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Healthcare centers | 59,021 workers in 117 companies that implemented the national Stress Check Program | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Overtime work hours (Self-reported) |

| 46 [68] | Taya et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 2905 workers from 17 worksites in Tokyo, Japan | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Continuous score | Presenteeism (Work Limitation Questionnaire, WLQ) |

| 47 [69] | Hayasaki et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 284 nurses from 12 wards in a hospital | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | The participants were dichotomized into high and low groups. For each subscale, high stress was defined by counting the number of non-desirable answers. | Ethical behaviors of nurses (Validated scale) |

| 48 [70] | Saito et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 49 teachers who have been employed for 5–10 years by nursing schools in an area in Japan | Stress response (29 items) | Continuous score | Self-efficacy (Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale, GSES) |

| 49 [71] | Okamoto et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 616 healthcare workers from 217 welfare facilities for the disabled in the Chugoku area, Japan | Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Respondents were grouped into tertiles (high, middle, and low). | Inappropriate care (Validated scale) |

| 50 [72] | Nagata et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 2693 employees at a pharmaceutical company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Psychological distress (K6) Work engagement (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, UWES) |

| 51 [73] | Okawa et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 103 employees at 17 corporations in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Participants were defined as high stress or not based on the Stress Check Program in Japan. | Autonomic nervous activity (Electrocardiography, photoplethysmography) |

| 52 [74] | Maeda et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional | Web surveys | 2000 female workers from an online research panel living with a partner | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Psychological health (mental health and vitality) (SF-36) |

| 53 [75] | Sakamoto et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 205 healthcare workers from a core hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Depression and anxiety (Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale, HADS) Chronic pain (Pain Catastrophizing Scale, PCS) |

| 54 [76] | Matsumoto and Yoshioka (2019) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 577 psychiatric nurses working at 13 psychiatric hospitals with more than 150 beds in the Chugoku area | Job stressors (17 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) | Continuous score | Negative Feeling toward patient (Negative Feeling toward Patient Frequency scale) Emotional, evaluative, informative, and instrumental support (Support-in-workplace scale) |

| 55 [77] | Kurebayashi (2019) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 271 general and 316 psychiatric nurses from seven hospitals in Japan | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Nursing skills (Self-Evaluation Scale of Oriented Problem Solving Behavior, OPSN) |

| 56 [78] | Watanabe and Yamauchi (2019) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 1075 full-time nurses working in four hospitals in Japan | Fatigue (3 items) | Continuous score | Motivation for overtime work (Self-developed, validated in the study) |

| 57 [79] | Fukunaga et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 312 teachers who intended to change occupations from nursing schools in eight prefectures | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (3 items) Physical stress response (2 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Identity of nurses and nursing teachers (Validated scale) |

| 58 [80] | Yoneyama et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 215 female nurses from advanced treatment hospitals in Kanto area, Japan | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Recognition of the organization (Validated scale) |

| 59 [81] | Inaba (2018) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 318 female nurses working in a private hospital for one or more years | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Job control (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Emotional demands (1 item) Role conflict (1 item) Work–self balance (negative) (1 item) Role clarity (1 item) Career opportunity (1 item) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Monetary/status reward (1 item) Esteem reward (1 item) Job security (1 item) Leadership (1 item) Interactional justice (1 item) Workplace where people compliment each other (1 item) Workplace where mistakes are acceptable (1 item) Collective efficacy (1 item) Trust with management (1 item) Preparedness for change (1 item) Respect for individuals (1 item) Fair personnel evaluation (1 item) Diversity (1 item) Career development (1 item) Work–self balance (positive) (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) Satisfaction with family life (1 item) Workplace harassment (1 item) Workplace social capital (1 item) | Continuous score | Subjective well-being (Single item) |

| 60 [82] | Sato (2018) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 109 workers from four worksites | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) | Continuous score Participants were defined as high stress or not based on the Stress Check Program in Japan. | Risk of periodontal disease (Saliva sampling) |

| 61 [83] | Horie et al. (2018) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 18 faculty staff members from care worker schools | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Burnout (Maslach Burnout Inventory, MBI) |

| 62 [84] | Nakamura and Mizukami (2018) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 657 healthcare workers at nine elderly nursing homes | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Work value (Work value scale) Assertive mind (Assertive Mind Scale) Self-efficacy (Generalized Self-efficacy Scale, GSES) Sense of coherence (Japanese sense of coherence scale: SOC-13) Communication skills (ENDCOREs) Working behaviors (Working behavior scale) Problem solution ability (Problem solution ability scale) |

| 63 [85] | Enoki et al. (2018) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 664 workers from a call center | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Sleeping time (Self-reported) |

| 64 [86] | Okada et al. (2018) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 108 female nurses who are wives or mothers from two general hospitals in Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Continuous score | Mental health (28-item General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-28) |

| 65 [87] | Adachi and Inaba (2018) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 368 workers from a single worksite | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies for Depression scale, CES-D) |

| 66 [88] | Sakamoto et al. (2018) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 38 workers of the rehabilitation department of a core hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Pain catastrophizing (The Pain Catastrophizing Scale, PCS) Depression and anxiety (Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale, HADS) |

| 67 [89] | Yada et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 68 psychiatric assistant nurses and 140 psychiatric registered nurses from six psychiatric hospitals. | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Psychiatric nurse job stressor (Psychiatric Nurse Job Stressor Scale, PNJSS) |

| 68 [90] | Enoki et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 538 employees from a call center | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Electrocardiography (EDG-9130 electrocardiograph) |

| 69 [91] | Tsutsumi et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | Web surveys | 1650 workers via an online survey | Job stressors (17 items) Stress response (29 items) Social support (9 items) | Participants were defined as high stress or not based on the Stress Check Program in Japan. | Psychological distress (K6 scale) |

| 70 [92] | Saijo et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | Public sectors | 2535 employees in local government, Asahikawa city, Hokkaido | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) | Continuous score | Work impairment Work output (13-item Stanford Presenteeism Scale, SPS-13) |

| 71 [93] | Sakuraya et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 894 employees from a manufacturing company | Psychological stress response, except vigor (15 items) | Continuous score | Job crafting (Japanese version of the Job Crafting Questionnaire) |

| 72 [94] | Toyama and Mauno (2017) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 489 eldercare nurses in special nursing homes | Social support (9 items) Realization of creativity (3 items) | Continuous score | Emotional intelligence (Emotional Intelligence Scale, EQS) |

| 73 [95] | Izawa et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 123 middle-aged workers from hospitals and research institutes in Kanagawa prefecture | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) | The job strain index was calculated by dividing job demands by job control. | Cortisol level in fingernails (Fingernail sampling) |

| 74 [96] | Watanabe et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | Existing cohorts | 2502 parents (1251 couples) from the Tokyo Work–Family INterface (TWIN) study | Fatigue (3 items) | Continuous score | Job demands (Four items from Furda, 1995) Family demands (Five items from Peeters, 2005) |

| 75 [97] | Yoshimoto et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 203 workers from a single hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) | Standardized scores were developed with a five-point scale based on a representative sample of Japanese workers. In addition, the participants were dichotomized into “not stressed” and “stressed” groups. | Low back pain (Von Korff’s grading method) |

| 76 [98] | Sakagami (2016) | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of faculty staff members or alumni of universities | 112 male researchers from two academic institutions | Qualitative job overload (3 items) | Continuous score | Ego aptitude (Tokyo University Egogram Version II, TEG-II) |

| 77 [99] | Yamada et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | Existing cohorts | 1764 workers from a pain-associated cross-sectional epidemiological study | Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) | Social support was used in quartiles of scores. Job satisfaction was classified into four categories: dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, relatively satisfied, or satisfied. | Chronic pain (11-point Numeric Rating Scale, NRS) Health-related quality of life (Euro Quality of Life, EQ-5D) |

| 78 [100] | Otsuka et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 42,499 workers from 61 organizations | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Job control (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Participants were divided by each mean subscale score. | Suicidal ideation (Single item) |

| 79 [101] | Watanabe et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 4543 employees from a beverage manufacturing company | Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) | Continuous score | Serum lipids (Blood sampling) |

| 80 [102] | Adachi and Inaba (2016) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 368 workers from a single worksite | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Depression (K10 scale) |

| 81 [103] | Kawahito (2016) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 34 middle-aged workers from a manufacturing company | Depression (6 items) | Continuous score | Self-complexity (Trait sort test) |

| 82 [104] | Maruya and Tanaka (2016) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 29 care workers in a facility for persons with intellectual disabilities | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Quality of life (26-item World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire, WHO QOL26) |

| 83 [105] | Fujita et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 440 workers from 35 units of a health care corporation | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor and coworker support (6 items) | Continuous score | Work engagement (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, UWES) |

| 84 [106] | Saijo et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | Public sectors | 2121 employees in the local government of Asahikawa city, Hokkaido | Job demands (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Scores were dichotomized based on the median values. | Depression (Japanese version of Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9) Burnout (Japanese version of Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey, MBI-GS) Insomnia (Athens Insomnia Scale, AIS) |

| 85 [107] | Morimoto et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 189 healthcare professionals from three general hospitals. | Psychological stress response (18 items) | Continuous score | Coping orientation Appraisal of coping acceptability (Coping Scale for Task stressors and Job evaluation stressors, CSTJ; Coping Scale for Interpersonal stressors, CSI) |

| 86 [108] | Kagata et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 306 female hospital ward nurses in the Kanto region | Psychological stress response except for vigor (15 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Emotional labor (Emotional Labor Inventory for Nurses, ELIN) Work engagement (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, UWES) |

| 87 [109] | Lee et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 276 workers (126 high-skilled foreign workers and 150 Japanese workers) | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) Satisfaction with family life (1 item) | Continuous score | Anxiety Depression Physical complaints (Mutual Intercultural Relations in Plural Societies Questionnaire, MIRIPSQ) |

| 88 [110] | Kato et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 837 nurses from 5 general hospitals in Hokkaido | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Excessive daytime sleepiness (Japanese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, JESS) |

| 89 [111] | Inaba and Inoue (2015) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 195 female nurses working in a general hospital for one or more years | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Job control (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Emotional demands (1 item) Role conflict (1 item) Work–self balance (negative) (1 item) Role clarity (1 item) Career opportunity (1 item) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Monetary/status reward (1 item) Esteem reward (1 item) Job security (1 item) Leadership (1 item) Interactional justice (1 item) Workplace where people compliment each other (1 item) Workplace where mistakes are acceptable (1 item) Collective efficacy (1 item) Trust with management (1 item) Preparedness for change (1 item) Respect for individuals (1 item) Fair personnel evaluation (1 item) Diversity (1 item) Career development (1 item) Work–self balance (positive) (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) Satisfaction with family life (1 item) Workplace harassment (1 item) Workplace social capital (1 item) Work engagement (1 item) | Continuous Score | Burnout (Pine’s burnout scale) |

| 90 [112] | Nakamura and Mizukami (2015) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 108 healthcare workers at 31 nursing home | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Sense of coherence (Japanese sense of coherence scale: SOC-13) |

| 91 [113] | Igarashi and Iijima (2015) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 99 female workers at five small–middle-sized companies | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Quality of life (MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey version2: SF-36) |

| 92 [114] | Ohta et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 1558 workers from an information technology company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor and coworker support (6 items) | Job stress scores were calculated by dividing job demand by job control. Social support was used as continuous scores. | Mental health (28-item General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-28) |

| 93 [115] | Saijo et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of faculty staff members or alumni of universities | 494 physicians from the entire alumni population of Asahikawa Medical University | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Job demands and job control scores were each dichotomized at a median value, and job strain was categorized. Social support was used in continuous score. | Depressive symptoms (Japanese version of Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9) Burnout (Japanese version of Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey, MBI-GS) |

| 94 [116] | Horita and Otsuka (2014) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 200 workers from three manufacturing companies | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) | Continuous score | Interpersonal helping behavior (Japanese version of Organizational Citizenship Behavior scale) |

| 95 [117] | Matsuzaki et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 1169 female registered nurses from 26 public hospitals and two private hospitals | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 items) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Job satisfaction (1 item) | Continuous score | Menopausal symptoms (Greene’s Climacteric Scale) |

| 96 [118] | Yoshida et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 102 male and female nurses from a university hospital | Stress response (29 items) | Standardized scores were developed on a five-point scale based on a representative sample of Japanese workers. | Sense of coherence (Japanese sense of coherence scale: SOC-13) |

| 97 [119] | Yada et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 244 psychiatric male and female nurses from six psychiatric hospitals | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Psychiatric nurse job stressor (Psychiatric Nurse Job Stressor Scale, PNJSS) |

| 98 [120] | Kikuchi et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 386 nurses from a general hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | Continuous score | Depression (K6 scale) Sense of coherence (Japanese sense of coherence scale: SOC-13) |

| 99 [121] | Nakata et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 137 male white-collar workers from a trading company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) | The job strain index was calculated by dividing job demands by job control. | Inflammatory markers(Blood sampling)Social support(Japanese version of the Generic Job Stress Questionnaire, GJSQ) |

| 100 [122] | Morimoto and Shimada (2014) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 737 employees from an information technology company | Psychological stress response (18 items) | Continuous score | Coping strategies Appraisal of coping acceptability (Coping Scale for Task Stressors and Job Evaluation Stressors, CSTJ; Coping Scale for Interpersonal Stressors, CSI) Motivation for using the chosen coping strategy (Reason for Selection of Coping Scale, RSC) |

| 101 [123] | Maruya et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 33 child-care supporters working at Children and Family Support Centers in four cities in Tokyo | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Quality of life (26-item World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire, WHO QOL26) |

| 102 [124] | Ikeshita et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 98 nurses working in operating rooms | Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Job and life satisfaction (2 items) | The participants were dichotomized into high and low groups. For the psychological stress response, ≥14 and ≥13 indicated a high score in men and women, respectively. For the physical stress response, ≥5 and ≥6 indicated a high score in men and women, respectively. Standardized scores were developed on a five-point scale based on a representative sample of Japanese workers. | General self-efficacy (General Self-Efficacy Scale, GSES) |

| 103 [125] | Yada et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 60 psychiatric nurses | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Psychiatric nurse job stressor (Psychiatric Nurse Job Stressor Scale, PNJSS) |

| 104 [126] | Sato (2014) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 160 ward nurses from two hospitals in a prefecture | Poor physical environment (1 item) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Work environment perception (Items based on the Home and Community Environment, HACE) |

| 105 [127] | Kikuchi et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 330 female nurses from a general hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor and coworker support (6 items) | Continuous score | Depressive symptoms (Five-item screening from the Self-Rating Depression Scale and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) |

| 106 [128] | Morimoto et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 738 employees in an information technology company | Psychological stress response (18 items) | Continuous score | Coping methods Appraisal of coping acceptability (Coping Scale for Task stressors and Job evaluation stressors, CSTJ; Coping Scale for Interpersonal stressors, CSI) Appraisal of a stressor’s controllability (Cognitive Appraisal Rating Scale, CARS) |

| 107 [129] | Sugawara et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 5878 middle-aged workers randomly selected companies in the Aomori prefecture | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Job satisfaction (1 item) | Job demands were calculated by quantitative, qualitative, and physical demands. Job compatibility was calculated by skill utilization and suitable jobs. Each variable was dichotomized based on the number of agreements for the items | Suicidal ideation Depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies for Depression scale, CES-D) |

| 108 [130] | Okuno et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 284 nurses working from a general hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Job control (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) Satisfaction with family life (1 item) | Standardized scores were developed on a 5-point scale based on a representative sample of Japanese workers. For social support and satisfaction, continuous scores were used. | Post-traumatic growth (Japanese version of Posttraumatic Growth Inventory, PTGI-J) Burnout (Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, CBI) |

| 109 [131] | Yoshida et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 517 nurses from a university hospital | Psychological stress response (18 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Standardized scores were developed on a five-point scale based on a representative sample of Japanese workers. | Sense of coherence(Japanese Sense of Coherence scale: SOC-13)Coping(Brief Scales for Coping Profile; BSCP) |

| 110 [132] | Shigehisa (2013) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 357 nurses | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) | Continuous score | Caring behaviors (41-item caring behavior scale) |

| 111 [133] | Koizumi et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 225 female nurses from a general hospital | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Resilience (Sukemune-Hiew Resilience Test, SHR) |

| 112 [134] | Hosoda et al. (2012) | Cross-sectional | Fire defense stations/headquarters | 246 male firefighters from a local fire defense headquarters | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Support from family and friends (3 items) | Continuous score | Alcohol dependence (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, AUDIT) |

| 113 [135] | Sunami and Yaeda (2012) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 472 novice nurses from 15 hospitals with 300 or more beds | Psychological stress response (18 items) | Continuous score | Social support (Mentoring scale from Ono, 1998) Self-esteem (Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale) |

| 114 [136] | Taniguchi et al. (2012) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 897 care workers working in 35 nursing facilities | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Psychological stress response (18 items) | Continuous score | Workplace bullying (Negative Acts Questionnaire, NAQ) |

| 115 [137] | Amagasa and Nakayama (2012) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 1160 sales workers | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) | Continuous score | Depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies for Depression scale, CES-D) |

| 116 [138] | Hayashi et al. (2011) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 1804 full-time regular employees from an electronics company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor and coworker support (6 items) | Continuous score | Organizational justice(Organizational Justice Questionnaire, OJQ)Organizational citizenship behavior(3-item scale based on Williams and Anderson, 1991)Job satisfaction(6-item scale from Tanaka, 1995) |

| 117 [139] | Ugaki et al. (2010) | Cross-sectional | Nursing or welfare facilities | 150 nurses who participated in the psychoeducation program in a prefecture | Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Suitable jobs (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) | Continuous score | Coping traits (Brief Stress for Coping Scale, BSCP) |

| 118 [140] | Katayama (2010) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 123 nurses from five hospitals with 300 or more beds | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Emotional labor(Emotional Labor Inventory for Nurses, ELIN) |

| 119 [141] | Shimazu et al. (2010) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 757 workers from a construction machinery company | Psychological stress response except for vigor (15 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Workaholism (Dutch Workaholism Scale, DUWAS) Active coping (Brief Stress for Coping Scale, BSCP) Job performance (World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire, WHO-HPQ) |

| 120 [142] | Shimazu and Schaufeli (2009) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 776 employees from a construction machinery company | Psychological stress response (18 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) Satisfaction with family life (1 item) | Continuous score | Work engagement (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, UWES) Workaholism (Dutch Workaholism Scale, DUWAS) Job performance (World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire, WHO-HPQ) |

| 121 [143] | Otsuka et al. (2009) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 808 middle-aged workers from a company in Kanagawa Prefecture | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) | The total scores for the two scales were dichotomized at the median, and high job strain was defined as the combination of high job demands and low job control. | Arterial wave reflection (Automated applanation tonometric method) |

| 122 [144] | Katsuyama et al. (2009) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 243 employees who worked at a manufacturing company and a local hospital | Depression (6 items) | Continuous score | Polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter (5HTT) Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) D2 dopamine receptor (DRD2) Cytochrome P450 2A6 (CYP2A6) |

| 123 [145] | Sato et al. (2009) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 24,685 employees from a computer, software, and network company | Stress responses (29 items) | Continuous score based on a five-point scale | Overtime work (Self-reported) |

| 124 [146] | Tanbo (2008) | Cross-sectional | Healthcare centers | 62 workers who took a health examination at a health institute | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Health Practice Index (Morimoto’s Health Practical Index, HPI) |

| 125 [147] | Mitani et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | Fire defense stations/headquarters | 128 firefighters from a fire department | Job stressors (17 items) Social support (9 items) | Continuous score | Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Japanese version of Impact Event Scale, IES-R-J). |

| 126 [148] | Katsuyama et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 243 employees at a manufacturing company and a local hospital | Depression (6 items) | Continuous score | Serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms (5HTT, Leukocytes in blood sample) |

| 127 [149] | Ikeda et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 76 doctors and 285 female nurses working at a general hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Mental health (30-item General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-30) |

| 128 [150] | Katsuyama (2008) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 133 manufacturing workers and 113 hospital workers | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Health risk scores were calculated by the four subscales | Polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter (5HTT) Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) D2 dopamine receptor (DRD2) |

| 129 [151] | Suwazono et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 3481 daytime employees from a steel company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Job control (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Suitable jobs (1 item) | Job demands were defined as high when the level of job demands was scored six points or more. Job control, interpersonal conflicts, and suitable jobs were defined as unfavorable when the level of each subscale was two points or more. | Fatigue symptoms (Cumulative Fatigue Symptom Index, CFSI) |

| 130 [152] | Umehara et al. (2007) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 590 respondents who worked more than 35 h per week as a pediatrician | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Working hours (Self-reported) Work schedule (Self-reported, number of night duties in the past month, number of weekend duties in the past month, days with on-call duties in the past month, workdays with no overtime in the past month, days off with no work in the past month, days off with some work in the past month) |

| 131 [153] | Mineyama et al. (2007) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 203 workers at a brewing company in the Kansai (west) region | Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Psychological stress response (18 items) | Continuous score | Active listening attitude of supervisors (Active Listening Attitude Scale, ALAS) |

| 132 [154] | Tanihara and Taguchi (2007) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 49 workers from a small-sized worksite | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Meaningfulness of work (1 item) Vigor (3 items) Anger-irritability (3 items) Fatigue (3 items) Anxiety (3 items) Depression (6 items) Physical stress response (11 items) | Continuous score | Burnout (Maslach Burnout Inventory, MBI) |

| 133 [155] | Washizuka and Ikeo (2007) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 175 female nurses working in shift time at a hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Job control (3 items) Suitable jobs (1 item) Psychological stress response (18 items) Physical stress response (11 items) Supervisor and coworker support (6 items) | Simple scoring method | Breslow health-related behaviors (Seven-item Breslow’s health behaviors) |

| 134 [156] | Ikeda et al. (2007) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 405 female nurses working at a general hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Mental health (30-item General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-30) |

| 135 [157] | Toh et al. (2006) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 144 novice nurses at a university hospital | Psychological stress response (18 items) | Continuous score | Ego state (Egogram) |

| 136 [158] | Mitani et al. (2006) | Cross-sectional | Fire defense stations/headquarters | 231 participants belonging to two fire departments | Job stressors (17 items) Social support (9 items) | Continuous score | Burnout (Maslach Burnout Inventory, MBI) Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Japanese version of Impact Event Scale, IES-R-J). |

| 137 [159] | Ushiki et al. (2006) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 316 female nurses from a hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (6 items) | Continuous score | Depression Anxiety (Goldberg’s anxiety-depression scale) |

| 138 [160] | Mitani and Shirakawa (2005) | Cross-sectional | Fire defense stations/headquarters | 37 firefighters working at a fire department in Kyoto city | Job stressors (17 items) | Participants were dichotomized into high and low groups based on the mean score. | Autonomic nervous activity (Electro-cardiogram) Serum cortisol Norepinephrine (Blood sampling) |

| 139 [161] | Harada et al. (2005) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 4962 male workers from a steel company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Job control (3 items) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Suitable jobs (1 item) | Job demands were defined as unfavorable when six or more questions on job demands were ticked by a participant. Job control, interpersonal conflict, and suitable jobs were defined as unfavorable when two or more items were ticked for each item. | Shift work (Self-reported) |

| 140 [162] | Shimazu et al. (2005) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 726 male non-managers at a large electrical company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Active coping (Job Stress Scale, JSS) |

| 141 [163] | Katsuyama et al. (2005) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 133 workers from a manufacturing company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Health risk scores were calculated by the four subscales | Polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter (5HTT) Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) |

| 142 [164] | Shimazu et al. (2004) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 867 employees from a large electrical company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Job satisfaction (10-item scale from McLean, 1979) |

| 143 [165] | Miki et al. (2004) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 695 full-time nurses from a university hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Interpersonal conflict (3 items) Poor physical environment (1 item) Job control (3 items) Skill utilization (1 item) Suitable jobs (1 item) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) Job satisfaction (1 item) | Continuous score | Depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies for Depression scale, CES-D) |

| 144 [166] | Tsukamoto et al. (2004) | Cross-sectional | Private companies | 808 male workers from an informational technology company | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Job control (3 items) Supervisor support (3 items) Coworker support (3 items) | Continuous score | Depression (Zung Self-rating Depression Scale, SDS) |

| 145 [167] | Kotake et al. (2003) | Cross-sectional | Hospitals | 113 novice nurses at a university hospital | Quantitative job overload (3 items) Qualitative job overload (3 items) Physical demands (1 item) Job control (3 items) Suitable jobs (1 item) | Continuous score | Mental health (12-item General Health Questionnaire, GHQ-12) |

References

- Kivimäki, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Batty, G.D.; Fransson, E.I.; Heikkilä, K.; Alfredsson, L.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; Casini, A.; et al. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2012, 380, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimaki, M.; Virtanen, M.; Elovainio, M.; Kouvonen, A.; Vaananen, A.; Vahtera, J. Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart diseas—A meta-analysis. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health—A meta-analytic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. PRIMA-EF: Guidance on the European Framework for Psychosocial Risk Management: A Resource for Employers and Worker Representatives. 2008. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43966 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Cousins, R.; MacKay, C.J.; Clarke, S.D.; Kelly, C.; Kelly, P.J.; McCaig, R.H. ‘Management Standards’ work-related stress in the UK: Practical development. Work Stress 2004, 18, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Standard of Canada. Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace: Prevention, Promotion, and Guidance to Staged Implementation. 2013. Available online: https://www.healthandsafetybc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/CAN_CSA-Z1003-13_BNQ_9700-803_2013_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO45003:2021 Occupational Health and Safety Management: Psychological Health and Safety at Work: Guidelines for Managing Psychosocial Risks. 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/64283.html (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Kristensen, T.S.; Hannerz, H.; Hogh, A.; Borg, V. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire—A tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2005, 31, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejtersen, J.H.; Kristensen, T.S.; Borg, V.; Bjorner, J.B. The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, H.; Berthelsen, H.; Moncada, S.; Nubling, M.; Dupret, E.; Demiral, Y.; Oudyk, J.; Kristensen, T.S.; Llorens, C.; Navarro, A.; et al. The third version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Saf. Health Work 2019, 10, 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, J.J., Jr.; McLaney, M.A. Exposure to job stress: A new psychometric instrument. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1988, 14, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.J.; Koh, S.B.; Kang, D.; Kim, S.A.; Kang, M.G.; Lee, C.G.; Chung, J.J.; Cho, J.J.; Son, M.; Chae, C.H.; et al. Developing an Occupational Stress Scale for Korean employees. Korean J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 17, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y.; Luo, X.; He, X.; Yin, W. Development of construction workers job stress scale to study and the relationship between job stress and safety behavior: An empirical study in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naono-Nagatomo, K.; Abe, H.; Yada, H.; Higashizako, K.; Nakano, M.; Takeda, R.; Ishida, Y. Development of the School Teachers Job Stressor Scale (STJSS). Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2019, 39, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mert, S.; Aydin Sayilan, A.; Baydemir, C. Nurse Stress Scale (NSS): Reliability and validity of the Turkish version. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.W.; Kim, H.K. Job stress and its related factors among Korean dentists: An online survey study. Int. Dent. J. 2019, 69, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimomitsu, T.; Haratani, T.; Nakamura, K.; Kawakami, N.; Hyashi, T.; Hiro, H.; Arai, M.; Miyazaki, S.; Furuki, K.; Ohya, Y.; et al. Final development of the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire mainly used for assessment of the individuals. In The Ministry of Labor Sponsored Grant for the Prevention of Work-Related Illness; Kato, M., Ed.; Tokyo Medical University: Tokyo, Japan, 2000; pp. 126–138. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, A.; Kawakami, N.; Shimomitsu, T.; Tsutsumi, A.; Haratani, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Shimazu, A.; Odagiri, Y. Development of a short questionnaire to measure an extended set of job demands, job resources, and positive health outcomes: The New Brief Job Stress Questionnaire. Ind. Health 2014, 52, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakami, N.; Tsutsumi, A. The Stress Check Program: A new national policy for monitoring and screening psychosocial stress in the workplace in Japan. J. Occup. Health 2016, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousa, P.C.P.; Lucca, S.R. Psychosocial factors in nursing work and occupational risks: A systematic review. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74, e20200198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Pereira, A. Exposure to psychosocial risk factors in the context of work: A systematic review. Rev. Saude Publica 2016, 50, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugito, M.; Okada, Y.; Torimoto, K.; Enta, K.; Tanaka, Y. Work environment-related stress factors are correlated with diabetes development in workers with impaired glucose tolerance: A 5-year follow-up study using the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire (BJSQ). J. UOEH 2021, 43, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Kamino, T.; Yasuda, T.; Suganuma, A.; Sakane, N. Association between psychological distress and stress-related symptoms and increased risk of type 2 diabetes in male individuals: An observational study. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2020, 12, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachi, Y.; Inoue, A.; Eguchi, H.; Kawakami, N.; Shimazu, A.; Tsutsumi, A. Occupational stress and the risk of turnover: A large prospective cohort study of employees in Japan. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazaki, T.; Uechi, H.; Takenaka, K. Mental health promotion behaviors associated with a 6-Month follow-up on job-related mood among Japanese workers. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consul. 2020, 9, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sakata, K.; Komiya, A.; Li, Y. What makes employees’ work so stressful? Effects of vertical leadership and horizontal management on employees’ stress. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, A.; Tsutsumi, A.; Kachi, Y.; Eguchi, H.; Shimazu, A.; Kawakami, N. Psychosocial work environment explains the association of job dissatisfaction with long-term sickness absence: A one-year prospect study of Japanese employees. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, A.; Inoue, A.; Mafune, K.; Hiro, H. The effect of changes in overtime work hours on depressive symptoms among Japanese white-collar workers: A 2-year follow-up study. J. Occup. Health 2019, 61, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, H.; Furuta, N.; Kono, M.; Kabeya, M. Stress-buffering effect of coping strategies on interrole conflict among family caregivers of people with dementia. Clin. Gerontol. 2019, 42, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K.; Iwasaki, S.; Deguchi, Y.; Fukuda, Y.; Nitta, T.; Nogi, Y.; Mitake, T.; Inoue, K. Higher occupational stress and stress responses in public servants requiring long-term sickness absence due to mental disorders. Osaka City Med. J. 2018, 64, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi, A.; Shimazu, A.; Eguchi, H.; Inoue, A.; Kawakami, N. A Japanese Stress Check Program screening tool predicts employee long-term sickness absence: A prospective study. J. Occup. Health 2018, 60, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Y.; Iwasaki, S.; Deguchi, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Nitta, T.; Inoue, K. The effect of long-term sickness absence on coworkers in the same work unit. Ind. Health 2018, 56, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okita, S.; Daitoku, S.; Abe, M.; Arimura, E.; Setoyama, H.; Koriyama, C.; Ushikai, M.; Kawaguchi, H.; Horiuchi, M. Potential predictors of susceptibility to occupational stress in Japanese novice nurses—A pilot study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, A.; Inoue, A.; Mafune, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Hayashi, T.; Hiro, H. Changes in the psychosocial work characteristics and insulin resistance among Japanese male workers: A three-year follow-up study. J. Occup. Health 2016, 58, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraya, A.; Imamura, K.; Inoue, A.; Tsutsumi, A.; Shimazu, A.; Takahashi, M.; Totsuzaki, T.; Kawakami, N. Workplace social capital and the onset of major depressive episode among workers in Japan: A 3-year prospective cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, T.; Takaki, J.; Hirokawa, K.; Fujii, Y.; Harano, K. Associations of workplace bullying and harassment with stress reactions: A two-year follow-up study. Ind. Health 2016, 54, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Otsuka, Y.; Shimazu, A.; Kawakami, N. The moderating effect of health-improving workplace environment on promoting physical activity in white-collar employees: A multi-site longitudinal study using multi-level structural equation modeling. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, M.; Muto, T.; Haruyama, Y.; Yuhara, M.; Sairenchi, T.; Kato, R. Risk factors of recurrent sickness absence due to depression: A two-year cohort study among Japanese employees. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2015, 88, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kamiyama, K.; Kawakami, N. Workaholism vs. work engagement: The two different predictors of future well-being and performance. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 22, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsudaira, K.; Konishi, H.; Miyoshi, K.; Isomura, T.; Inuzuka, K. Potential risk factors of persistent low back pain developing from mild low back pain in urban Japanese workers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Sairenchi, T.; Haruyama, Y.; Taneichi, H.; Ishikawa, Y.; Muto, T. Relationship between the onset of depression and stress response measured by the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire among Japanese employees: A cohort study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Shimazu, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Shimada, K.; Kawakami, N. Work-self balance: A longitudinal study on the effects of job demands and resources on personal functioning in Japanese working parents. Work Stress 2013, 27, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuno, Y.; Banba, I.; Aono, A.; Azuma, K.; Okumura, J. A longitudinal study on the effect of stress experiences on self-growth one year later among human service professionals. Med. J. Kinki. Univ. 2013, 38, 115–124. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Urakawa, K.; Yokoyama, K.; Itoh, H. Sense of coherence is associated with reduced psychological responses to job stressors among Japanese factory workers. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M.; Iwasaki, K.; Sasaki, T.; Kubo, T.; Mori, I.; Otsuka, Y. Sleep, fatigue, recovery, and depression after change in work time control: A one-year follow-up study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 54, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimura, H.; Thériault, G. Impact of supervisor support on work ability in an IT company. Occup. Med. 2010, 60, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]