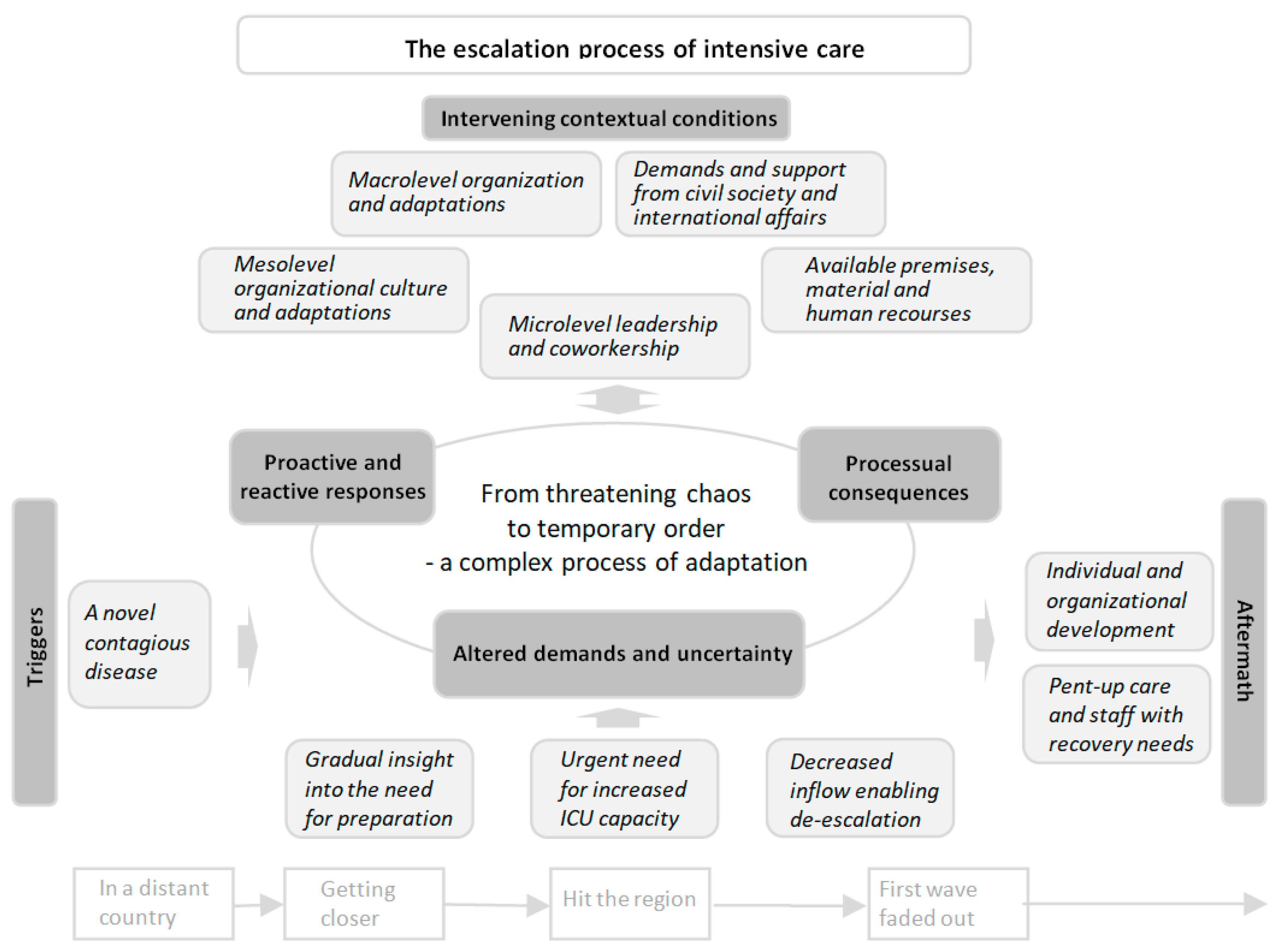

From Threatening Chaos to Temporary Order through a Complex Process of Adaptation: A Grounded Theory Study of the Escalation of Intensive Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Data Management and Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

“The first 4 weeks were chaos and a war zone; it was very noisy, and you had no control… Every day, every hour, you thought—I hope nothing goes wrong; I hope no patient dies on my shift… We learned a lot during this time, to be innovative and find different solutions; we were all like MacGyver! (#65).”

3.1. Triggers

“There was news about COVID-19, and we started to wake up a little when we saw that it could affect Sweden as well. At first it was pretty obvious that this was probably not as dangerous as it looked. Then, it quite quickly changed to “this could really happen to us”. Then, it happened very quickly and it hit us. We escalated intensive care at the last minute, I would say (#28).”

3.2. Altered Demands and Uncertainty

“I remember that everything happened at a breakneck speed, and no day was the same. Every day, there were new directives, new solutions, new personnel, new devices, new machines and new patients (#52).”

3.3. Proactive and Reactive Responses

“We had to lay the rails while driving, and it turned out well. As good as it gets when you do that, of course. But there were a lot of decisions that were very ad hoc. It was just like this, “okay, now we’ll do this,” “well, no, we’ll do it like this instead,” and we barely had time to keep a log of all the changes we made (#38).”

“There were a lot of changes in my way of working that I, as an ICU nurse, had to make or completely let go of to be able to handle the situation. … I had the feeling that patient safety was lower than in the case of regular ICU care even though we all did the best we could for the patients to survive and receive relatively safe care (#47).”

3.4. Intervening Contextual Conditions

“I could sense a tremendous loyalty within the organization that made the impossible possible. I’m really impressed with how quickly the organization was put together; the employees just fixed it! (#23).”

“In general, you can say that the response in our region was driven by the operational level. It was mainly ideas and initiatives from the Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care and the Department of Infectious Diseases that created the action plans that formed the basis of the region’s way of facing the pandemic. Many decisions were made locally, anchored with partners and realized before senior management was informed of what was happening. From my side, there is both a frustration that the management did not act and a relief that what we said at the operational level was listened to (#68).”

“It was quite late that the door to other hospitals was opened among our intensive care units in the country… If you have had a different mindset, that we are together in this, Sweden is ONE intensive care clinic… Then, I think, we would have managed better (#28).”

3.5. Processual Consequences

“It was terrible! The room was not adapted for ICU care. I had never been to the ward and didn’t know the premises; the staff who would help were not used to intensive care, so I had to supervise them as well, even though I had two really ill ICU patients… This day was absolutely not safe for the patients! (#45).”

“It’s been an incredible journey that you were not prepared for. But that it worked, sort of. It’s really cool (#26).”

“What has been tough is that we have not had general ICU beds, which I think has meant that patients with higher monitoring needs have ended up in a regular ward or that we have had to transport unstable patients unnecessarily (#35).”

3.6. Aftermath

“It’s like an experience that I would have liked to have avoided in a way, but now that it’s here, I don’t want to be without it…How we did in March-April, we didn’t do at all in May-June. We did it differently, treated differently; we learned a lot… At that time, you were so up to it in some way, high on adrenaline or what should I say. Then, when you got a vacation, which we actually got for the summer, the air went out of you. And the air hasn’t really returned yet… So, there are thoughts about both the present and the future and how people will cope (#80).”

3.7. Recommendaions Regarding How to Optimize the Prerequisites for Resilient Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Relations between the EPIC Model and Existing Frameworks

4.2. The Complex Process of Adaptation

4.3. Adaptive Capacity as Both an Enabler and a Challenge within a CAS

4.4. Clinical Implications

4.5. Methodological Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paschoalotto, M.A.C.; Lazzari, E.A.; Rocha, R.; Massuda, A.; Castro, M.C. Health systems resilience: Is it time to revisit resilience after COVID-19? Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 320, 115716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, S.; Aase, K.; Billett, S.; Canfield, C.; Røise, O.; Njå, O.; Guise, V.; Haraldseid-Driftland, C.; Ree, E.; Anderson, J.E.; et al. Defining the boundaries and operational concepts of resilience in the resilience in healthcare research program. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturmberg, J.P.; Martin, C.M. COVID-19—How a pandemic reveals that everything is connected to everything else. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2020, 26, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, A.; Rajaleid, K.; Demmelmaier, I. The Work Environment during Coronavirus Epidemics and Pandemics: A Systematic Review of Studies Using Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed-Methods Designs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2022, 19, 6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelmann, J.; Webb, E.; Williams, G.A.; Hernández-Quevedo, C.; Maier, C.B.; Panteli, D. European countries’ responses in ensuring sufficient physical infrastructure and workforce capacity during the first COVID-19 wave. Health Policy 2022, 126, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, Y.M.; Azoulay, E.; Al-Dorzi, H.M.; Phua, J.; Salluh, J.; Binnie, A.; Hodgson, C.; Angus, D.C.; Cecconi, M.; Du, B.; et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic will change the future of critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, M.S.; Kattainen, S.; Haase, N.; Buanes, E.A.; Kristinsdottir, L.B.; Hofsø, K.; Laake, J.H.; Kvåle, R.; Hästbacka, J.; Reinikainen, M.; et al. A descriptive study of the surge response and outcomes of ICU patients with COVID-19 during first wave in Nordic countries. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2022, 66, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-II in Practice: Developing the Resilience Potentials; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Plsek, P.E.; Greenhalgh, T. Complexity science: The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001, 323, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J.; Churruca, K.; Ellis, L.A.; Long, J.; Clay-Williams, R.; Damen, N.; Herkes, J.; Pomare, C.; Ludlow, K. Complexity Science in Healthcare—Aspirations, Approaches, Applications and Accomplishments: A White Paper; Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University: Sydney, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://www.mq.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/683895/Braithwaite-2017-Complexity-Science-in-Healthcare-A-White-Paper-1.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Braithwaite, J.; Ellis, L.A.; Churruca, K.; Long, J.C.; Hibbert, P.; Clay-Williams, R. Complexity science as a frame for understanding the management and delivery of high quality and safer care. In Textbook of Patient Safety and Clinical Risk Management; Donaldson, L., Ricciardi, W., Sheridan, S., Tartaglia, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 375–391. [Google Scholar]

- Reiman, T.; Rollenhagen, C.; Pietikäinen, E.; Heikkilä, J. Principles of adaptive management in complex safety–critical organizations. Saf. Sci. 2015, 71, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.E.; Ross, A.J.; Macrae, C.; Wiig, S. Defining adaptive capacity in healthcare: A new framework for researching resilient performance. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 87, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C. Moments of resilience: Time, space and the organisation of safety in complex sociotechnical systems. In Exploring Resilience: A Scientific Journey from Practice to Theory; Wiig, S., Fahlbruch, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Grote, G.; Kolbe, M.; Waller, M.J. The dual nature of adaptive coordination in teams: Balancing demands for flexibility and stability. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 8, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.D. The theory of graceful extensibility: Basic rules that govern adaptive systems. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2018, 38, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyng, H.B.; Macrae, C.; Guise, V.; Haraldseid-Driftland, C.; Fagerdal, B.; Schibevaag, L.; Alsvik, J.G.; Wiig, S. Exploring the nature of adaptive capacity for resilience in healthcare across different healthcare contexts; a metasynthesis of narratives. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 104, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjurling-Sjöberg, P.; Wadensten, B.; Pöder, U.; Jansson, I.; Nordgren, L. Balancing intertwined responsibilities: A grounded theory study of teamwork in everyday intensive care unit practice. J. Interprofessional Care 2017, 31, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rednor, S.; Eisen, L.A.; Cobb, J.P.; Evans, L.; Coopersmith, C.M. Critical care response during the COVID-19 pandemic. Crit. Care Clin. 2022, 38, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F. The first eight months of Sweden’s COVID-19 strategy and the key actions and actors that were involved. Acta Pediatr. 2020, 109, 2459–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Swedish Intensive Care Registry, Output Data. Available online: http://www.icuregswe.org (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Berggren, K.; Ekstedt, M.; Joelsson-Alm, E.; Swedberg, L.; Sackey, P.; Schandl, A. Healthcare workers’ experiences of patient safety in the intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicentre qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 7372–7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Adverse Events in COVID-19 Patients during 2020–2021, in Swedish; Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021; Available online: https://skr.se/download/18.4810054185aaa3e03d63116/1674477590709/Skador_vid_vard_av_patienter_med_covid-19_2020-2021.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Salluh, J.I.F.; Kurtz, P.; Bastos, L.S.L.; Quintairos, A.; Zampieri, F.G.; Bozza, F.A. The resilient intensive care unit. Ann. Intensive Care. 2022, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anesi, G.L.M.; Lynch, Y.; Evans, L.M. A Conceptual and Adaptable Approach to Hospital Preparedness for Acute Surge Events Due to Emerging Infectious Diseases. Crit. Care Explor. 2020, 2, e0110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasa, E.; Mbau, R.; Gilson, L. What Is Resilience and How Can It Be Nurtured? A Systematic Review of Empirical Literature on Organizational Resilience. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2018, 7, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.; Johansson, B.J.E. Resilience is not a silver bullet—Harnessing resilience as core values and resource contexts in a double adaptive process. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 188, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyng, H.B.; Macrae, C.; Guise, V.; Haraldseid-Driftland, C.; Fagerdal, B.; Schibevaag, L.; Alsvik, J.G.; Wiig, S. Balancing adaptation and innovation for resilience in healthcare—A metasynthesis of narratives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjurling-Sjöberg, P.; Göras, C.; Lohela-Karlsson, M.; Nordgren, L.; Källberg, A.-S.; Castegren, M.; Condén Mellgren, E.; Holmberg, M.; Ekstedt, M. Resilient performance in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic (ResCOV): Study protocol for a multilevel grounded theory study on adaptations, working conditions, ethics and patient safety. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.; Ellokor, S.; Lehmann, U.; Brady, L. Organizational change and everyday health system resilience: Lessons from Cape Town, South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 266, 113407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Board of Health and Welfare. National Principles for Prioritization of Routine Healthcare during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Knowledge Support to Develop Regional and Local Guidelines; The National Board of Health and Welfare: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/ovrigt/nationella-principer-for-prioritering-av-rutinsjukvard-covid19.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Ghahramani, S.; Lankarani, K.B.; Yousefi, M.; Heydari, K.; Shahabi, S.; Azmand, S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Burnout Among Healthcare Workers During COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 758849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurin, T.A.; Wachs, P.; Bueno, W.P.; Kuchenbecker, R.d.S.; Boniatti, M.M.; Zani, C.M.; Clay-Williams, R. Coping with complexity in the COVID pandemic: An exploratory study of intensive care units. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2022, 32, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaye, V.E.; Reich, J.A.; Bosworth, B.P.; Stern, D.T.; Volpicelli, F.; Shapiro, N.M.; Hauck, K.D.; Fagan, I.M.; Villagomez, S.M.; Uppal, A.; et al. Collaborating across private, public, community, and federal hospital systems: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic response in NYC. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2020, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, J.; Catchpole, K.; Heather, E.; Nemeth, L.; Layne, D.; Nichols, M. Healthcare Team Resilience during COVID-19: A Qualitative Study. 14 March 2023; preprint (Version 1). Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2626478/v1(accessed on 17 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Pesenti, A.; Cecconi, M. Critical Care Utilization for the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early Experience and Forecast During an Emergency Response. JAMA 2020, 323, 1545–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.; Fulbrook, P.; Kleinpell, R.; Alberto, L. The Fifth International Survey of Critical Care Nursing Organizations: Implications for Policy. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2020, 52, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharowski, K.; Filipescu, D.; Pelosi, P.; Åkeson, J.; Bubenek, S.; Gregoretti, C.; Sander, M.; de Robertis, E. Intensive care medicine in Europe: Perspectives from the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2022, 39, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedish Government. Sweden during the Pandemic—Healthcare and Public Health Vol 2 (SOU 2021:89); Fritze: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021; Available online: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2021/10/sou-202189/ (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Swedish Government. Summary in English (SOU 2022:10); Fritze: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://coronakommissionen.com/publikationer/slutbetankande-sou-2022-10/ (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Bader, M.K.; Braun, A.; Fox, C.; Dwinell, L.; Cord, J.; Andersen, M.M.; Noakes, B.B.; Ponticiello, D. A California hospital’s response to COVID-19: From a ripple to a tsunami warning. Crit. Care Nurse 2020, 40, e1–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardi, T.; Gómez-Rojo, M.; Candela-Toha, A.; de Pablo, R.; Martinez, R.; Pestaña, D. Rapid response to COVID-19, escalation and de-escalation strategies to match surge capacity of Intensive Care beds to a large scale epidemic. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. Engl. Ed. 2021, 68, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbaz-Kurth, S.; Juvet, T.M.; Benzakour, L.; Cereghetti, S.; Fournier, C.-A.; Moullec, G.; Nguyen, A.; Suard, J.-C.; Vieux, L.; Wozniak, H.; et al. How things changed during the COVID-19 pandemic’s first year: A longitudinal, mixed-methods study of organisational resilience processes among healthcare workers. Saf. Sci. 2022, 155, 105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, J.; Ross, A.J.; Duncan, M.D.; Jaye, P.; Henderson, K.; Anderson, J.E. Emergency Department Escalation in Theory and Practice: A Mixed-Methods Study Using a Model of Organizational Resilience. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2017, 70, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, J. Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Saf. Sci. 1997, 27, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangachari, P.L.; Woods, J. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Mean Age (Min–Max) | Region | Data Source | Total Number | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | A | B | Written | Interview | |||

| Assistant nurses | 6 | - | 49 (36–58) | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Registered nurses 1 | 28 | 9 | 48 (28–62) | 22 | 15 | 30 | 7 | 37 |

| Physicians 2 | 5 | 11 | 50 (32–69) | 12 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 16 |

| Managers 3 | 10 | 1 | 50 (45–64) | 5 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Total | 49 | 21 | 48 (28–69) | 42 | 28 | 47 | 23 | 70 |

| Core Category | Main Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|---|

| From threatening chaos to temporary order through a complex process of adaptation | Triggers | A novel contagious disease |

| Gradual insights into the need for preparation | ||

| Urgent need for increased ICU capacity | ||

| Decreased inflow enabling de-escalation | ||

| Altered demands and uncertainty | Rapidly altered care conditions | |

| Extensive need for room and infection control | ||

| Demand–capacity imbalance regarding material and human resources | ||

| Increased demands on governance, collaboration and communication | ||

| Proactive and reactive responses | Preparing and planning to the best of one’s ability | |

| Reorganizing the management and information structure | ||

| Prioritizing and reorganizing patient flow | ||

| Restructuring and compensating premises and material resources | ||

| Redistributing staff and adjusting roles | ||

| Alterations and trade-offs in patient care | ||

| Intervening contextual conditions | Microlevel leadership and coworkership | |

| Available premises, material and human recourses | ||

| Mesolevel organizational culture and adaptations | ||

| Macrolevel organization and adaptations | ||

| Demands and support from civil society and international affairs | ||

| Processual consequences | Managing commitment and learning over time | |

| Diluted competence, impaired quality of care and patient safety | ||

| Impaired work environment and working conditions | ||

| Aftermath | Individual and organizational development | |

| Pent-up care and staff with recovery needs |

| System Level | Component | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Micro-level | Space |

|

| Stuff |

| |

| Staff |

| |

| System |

| |

| Science |

| |

| Meso-level | Space |

|

| Stuff |

| |

| Staff |

| |

| System |

| |

| Science |

| |

| Macro-level | Space |

|

| Stuff |

| |

| Staff |

| |

| System |

| |

| Science |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Göras, C.; Lohela-Karlsson, M.; Castegren, M.; Condén Mellgren, E.; Ekstedt, M.; Bjurling-Sjöberg, P. From Threatening Chaos to Temporary Order through a Complex Process of Adaptation: A Grounded Theory Study of the Escalation of Intensive Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20217019

Göras C, Lohela-Karlsson M, Castegren M, Condén Mellgren E, Ekstedt M, Bjurling-Sjöberg P. From Threatening Chaos to Temporary Order through a Complex Process of Adaptation: A Grounded Theory Study of the Escalation of Intensive Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(21):7019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20217019

Chicago/Turabian StyleGöras, Camilla, Malin Lohela-Karlsson, Markus Castegren, Emelie Condén Mellgren, Mirjam Ekstedt, and Petronella Bjurling-Sjöberg. 2023. "From Threatening Chaos to Temporary Order through a Complex Process of Adaptation: A Grounded Theory Study of the Escalation of Intensive Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 21: 7019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20217019

APA StyleGöras, C., Lohela-Karlsson, M., Castegren, M., Condén Mellgren, E., Ekstedt, M., & Bjurling-Sjöberg, P. (2023). From Threatening Chaos to Temporary Order through a Complex Process of Adaptation: A Grounded Theory Study of the Escalation of Intensive Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(21), 7019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20217019