Family Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Trait Mindfulness and Perceived Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Health Problems

1.2. Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Health Problems: Role of Trait Mindfulness

1.3. Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Health Problems: Role of Mindfulness and Perceived Stress

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Family Socioeconomic Status (SES)

2.2.2. Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)

2.2.3. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

2.2.4. Mental Health Problems: Anxiety

2.2.5. Mental Health Problems: Depression

2.2.6. Mental Health Problems: Externalizing Problems

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Common Method Biases Test

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Path Analysis

3.3. Serial Multiple Mediation Model

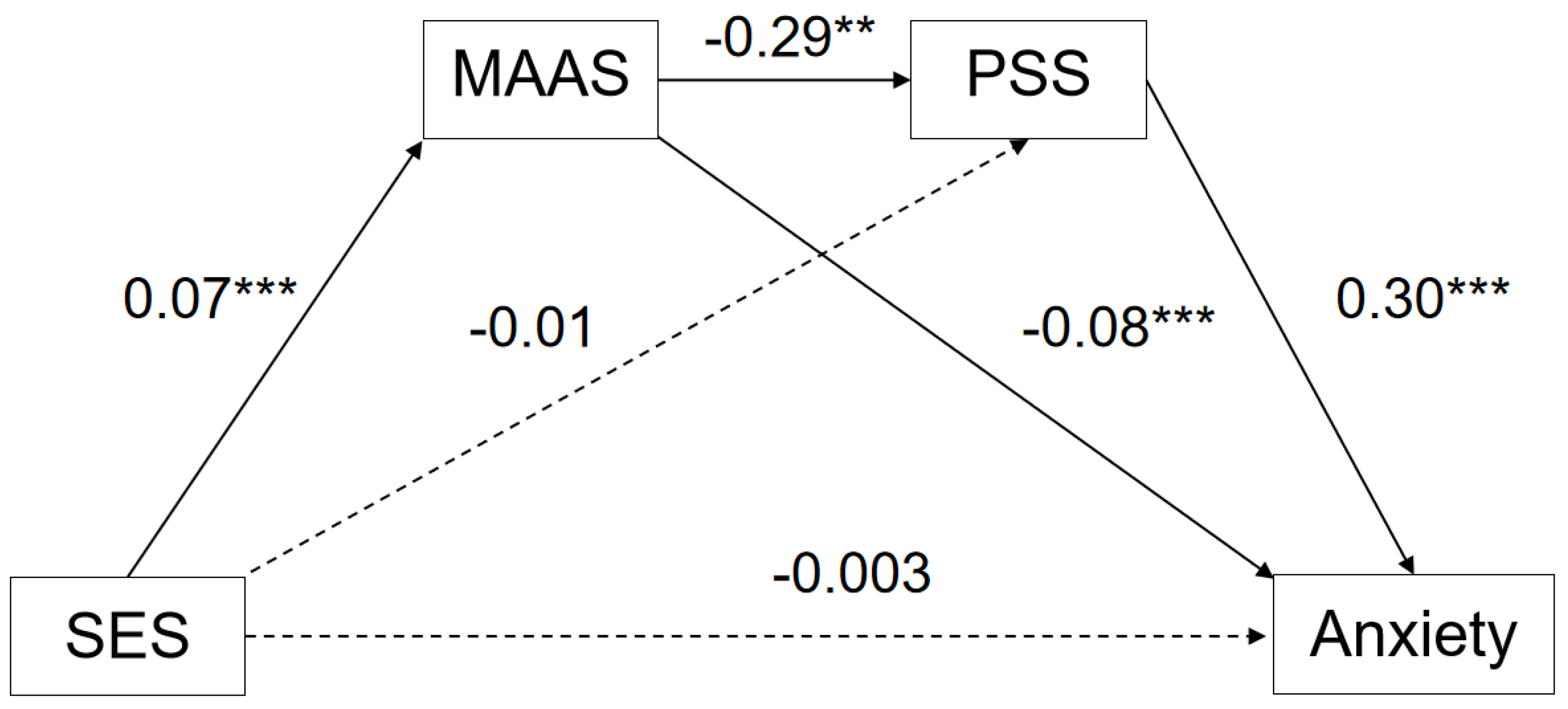

3.3.1. Serial Multiple Mediation Model: Anxiety

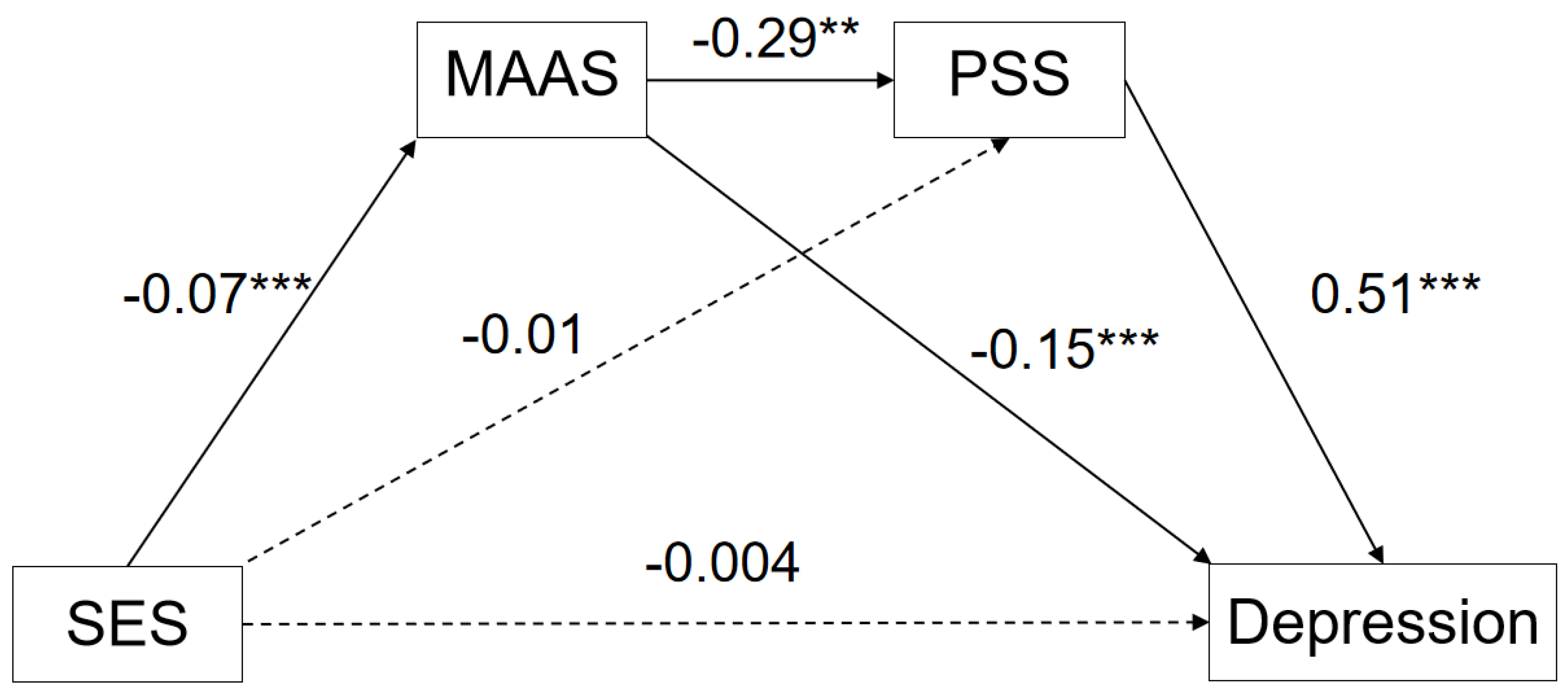

3.3.2. Serial Multiple Mediation Model: Depression

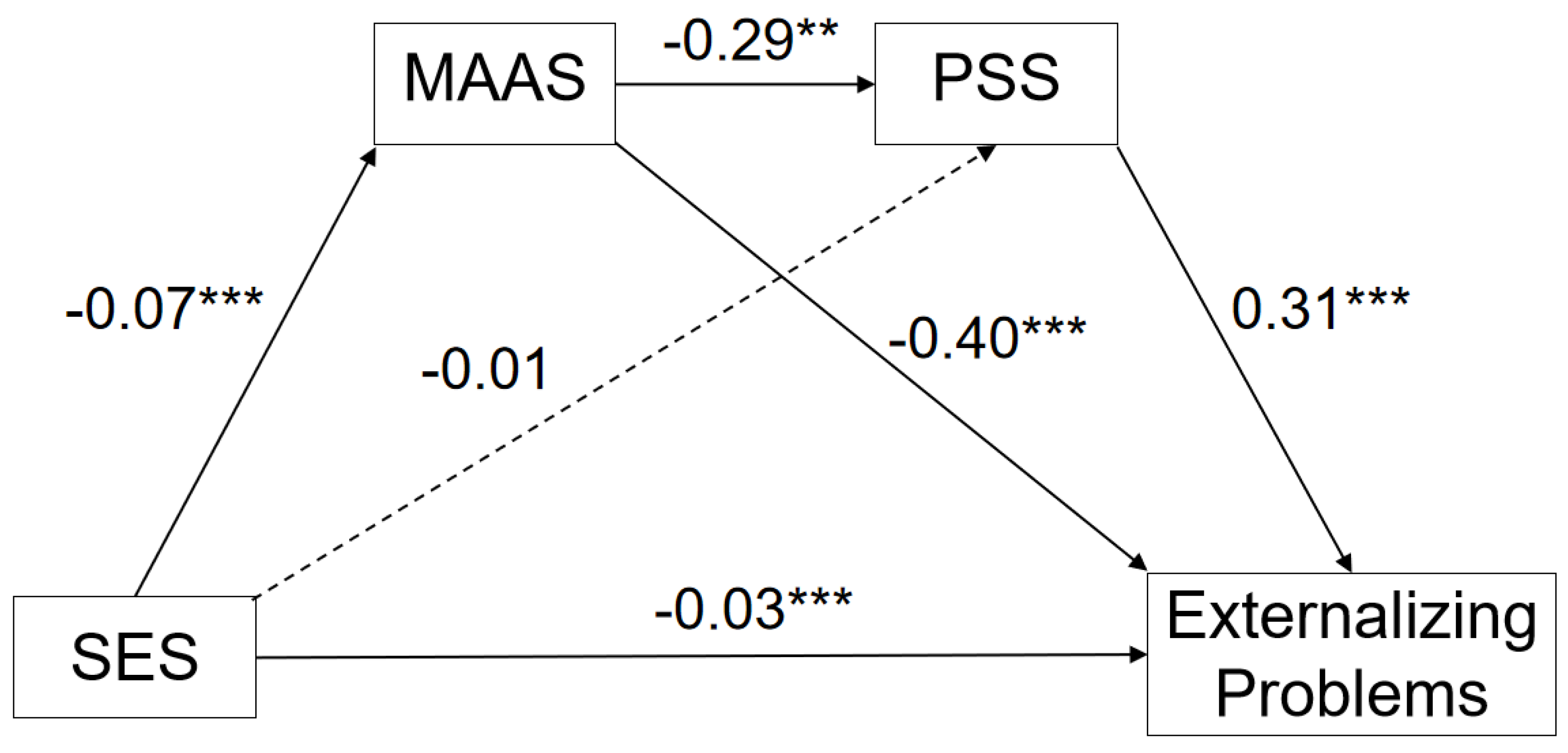

3.3.3. Serial Multiple Mediation Model: Externalizing Problems

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between SES and Mental Health Problems

4.2. Independent Mediating Effect of Trait Mindfulness

4.3. Serial Mediating Effect of Trait Mindfulness and Perceived Stress

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- The whole society should pay active attention to the development of low-SES adolescents, such as by establishing a sound welfare protection system for low-SES children during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 2.

- The chain-mediating effect suggests that perceived stress may lead to more mental health problems in low-SES adolescents. Therefore, teachers should learn as much as possible about students’ family socioeconomic backgrounds and pay timely attention to low-SES students when there is a large gap between the rich and the poor in the group during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 3.

- For adolescents with higher levels of stress perception, using interventions, such as Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, to prevent adolescents from internalizing the stress from SES into emotional problems or externalizing it into behavioral problems.

- 4.

- For mental health professionals, training adolescents in perceived stress relief skills might prove effective for supporting mental health problems in the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, to maximize their effectiveness, intervention programs should be developmentally sensitive to adolescent SES and level of stress relief competencies. Moreover, as trait mindfulness appears to influence mental health problems in adolescence, interventions should tackle this dimension first, which might have a snowball effect on the others.

Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Hu, T.; Hu, B.; Jin, C.; Wang, G.; Xie, C.; Chen, S.; Xu, J. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareeqa, S.B.; Ahmed, S.I.; Samar, S.S.; Yasin, W.; Zehra, S.; Monese, G.M.; Gouthro, R.V. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in china during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2021, 56, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francine, C.J.; Marjolein, Z.; Helma, M.Y. Koomen. Children’s perceptions of the relationship with the teacher: Associations with appraisals and internalizing problems in middle childhood. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 36, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.H.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, Y.C.; Fang, X.Y. The relationship between interpersonal relationship and internalization and externalization of high school students: The mediating role of self-esteem and the moderating effect of gender. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2017, 33, 708–718. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Leng, L.; Chen, H.J.; Fang, X.Y.; Shu, Z.; Li, X.Y. The effect of family socioeconomic status on the cognitive ability of migrant children: The mediating role of parenting style. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2017, 33, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. Mindfulness training on the resilience of adolescents under the COVID-19 epidemic: A latent growth curve analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 172, 110560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Yuan, Y.; Kang, M. Mindfulness Intervention on Adolescents’ Emotional Intelligence and Psychological Capital During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2022, 24, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.M.; Xue, S.; Kong, F. Dispositional mindfulness and perceived stress: The role of emotional intelligence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 78, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepping, C.A.; O’Donovan, A.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Hanisch, M. Individual differences in attachment and eating pathology: The mediating role of mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 75, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepping, C.A.; Duvenage, M. The origins of individual differences in dispositional mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Brown, K.W.; Creswell, J.D. How integrative is attachment theory? Unpacking the meaning and significance of felt security. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michal, M.; Beutel, M.E.; Jordan, J.; Zimmermann, M.; Wolters, S.; Heidenreich, T. Depersonalization, mindfulness, and childhood trauma. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.F.; Zhang, W.Y.; Jiao, G.S.; Yang, G. Effect of parenting style on creativity: The mediating role of mindfulness. Med. Educ. Res. Pract. 2019, 27, 811–816. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Gonnella, C.; Marcynyszyn, L.A.; Gentile, L.; Salpekar, N. The role of chaos in poverty and children’s socioemotional adjustment. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, M.E. An indirect effects model of the association between poverty and child functioning: The role of children’s poverty-related stress. J. Loss Trauma 2007, 13, 156–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 62, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.; Xu, W.; Wang, X.M.; Liu, X.H. Self-acceptance mediates the relationship between mindfulness and perceived stress. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 116, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, E.J.; Kamarck, T.W.; Shiffman, S. Hostility moderates the effects of social support and intimacy on blood pressure in daily social interactions. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katherine, K. Aggravating conditions: Cynical hostility and neighborhood ambient stressors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2258–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzagalli, D.A. Depression, stress, and anhedonia: Toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 393–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.W.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, G.X. The relationship between stress and depression in adolescents: An analysis of moderated mediating effects. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 788–791. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, B.J.; Zhu, L.J.; Fang, X.T. The impact of pressure perception on depression in college students: A moderated mediation model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2018, 34, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nykliček, I.; Mommersteeg, P.M.C.; van Beugen, S.; Ramakers, C.; van Boxtel, G.J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and physiological activity during acute stress: A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2013, 32, 1110–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Funder, D.C.; Ozer, D.J. Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 2, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The role of socioeconomic status and parental investment in adolescent outcomes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 129, 106186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.L. Prestige Stratification in the Contemporary China: Occupational prestige measures and socio-economic index. Soc. Stud. 2005, 2, 74–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H. Socioeconomic status, parenting and child development: The Hollingshead four—factor index of social status and the socioeconomic index of occupations. Socioecon. Status Parent. Child Dev. 2003, 29–82. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yu, J. Family Socioeconomic Status and Toddlers’ Social Adjustment in Rural-to-urban Migration and Urban Families: The Roles of Maternal Sensitivity and Attachment Security. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2021, 37, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, J.H.; Peng, Y.S.; Zeng, X.R.; Zhou, H. The Chinese Version of Mindful Attention Awareness Scale-Children(MAAS-C): An Examination of Reliability and Validity. Psychol. Explor. 2021, 41, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Black, D.S.; Sussman, S.; Johnson, C.A.; Milam, J. Psychometric assessment of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) among Chinese adolescents. Assessment 2012, 19, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.Z.; Huang, H.T. An epidemiological study on stress among urban residents in social transition period. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 24, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Gao, J.F. Reliability and validity of the Self-Assessment Scale for Revision of Anxiety (SAS-CR). Chin. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.S.; Li, J. Reliability and validity of a short version of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in national adult population. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2011, 25, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.T.; Chen, Y.W.; Tian, S.J. Development of a Conduct Problem Tendency Inventory for Adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 17, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, K.A.; Gallo, L.C. Psychological Perspectives on Pathways Linking Socioeconomic Status and Physical Health. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 501–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Harrington, H.; Milne, B.J.; Polanczyk, G.; Pariante, C.M.; Poulton, R.; Caspi, A. Adverse childhood experiences predict adult risk factors for age-related disease: Depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Brain Behav. Immun. 2009, 23, s32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Wu, H.T. The relationship between low family socioeconomic status and adolescents’ social adjustment: The compensatory and moderating effects of gratitude. Psychol. Explor. 2012, 32, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, K.G.; McCandliss, B.D.; Farah, M.J. Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Dev. Sci. 2007, 10, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peverill, M.; Dirks, M.A.; Narvaja, T.; Herts, K.L.; Comer, J.S.; McLaughlin, K.A. Socioeconomic status and child psychopathology in the United States: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 83, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, K.; Trejnowska, A.; Darling, S. The relationship between dispositional mindfulness, attachment security and emotion regulation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R.P.; Khaleque, A.; Cournoyer, D.E. Parental acceptance-rejection: Theory, methods, cross-cultural evidence, and implications. Ethos 2005, 33, 299–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Grupe, W.D. Trait Mindfulness Moderates the Association Between Stressor Exposure and Perceived Stress in Law Enforcement Officers. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 2325–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.D.; Lindsay, E.K. How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, J.; Baer, R.A.; Lykins, E.L.B.; Olendzki, N. An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.C. The benefits of meditation vis-à-vis emotional intelligence, perceived stress and negative mental health. Stress Health 2010, 26, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Weinstein, N.; Creswell, J.D. Trait mindfulness modulates neuroendocrine and affective responses to social evaluative threat. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 2037–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.D.; Pacilio, L.E.; Lindsay, E.K.; Brown, K.W. Brief mindfulness meditation training alters psychological and neuroendocrine responses to social evaluative stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 731 (46.18%) |

| Female | 852 (53.82%) | |

| Grade | Tenth grade | 570 (36.01%) |

| Eleventh grade | 522 (32.96%) | |

| Twelfth grade | 491 (31.02%) | |

| Age | 14 years old | 326 (20.59%) |

| 15 years old | 490 (30.95%) | |

| 16 years old | 410 (25.90%) | |

| 17 years old | 357 (22.55%) | |

| Father’s education | Elementary school and below | 265 (16.75%) |

| Junior high school | 873 (55.18%) | |

| Senior/Vocational high school | 390 (24.65%) | |

| Junior college | 45 (2.84%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 10 (0.63%) | |

| Mother’s education | Elementary school and below | 518 (32.74%) |

| Junior high school | 821 (51.90%) | |

| Senior/Vocational high school | 229 (14.48%) | |

| Junior college | 13 (0.82%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 (0.06%) | |

| Master’s degree or above | 1 (0.06%) | |

| Annual household income | Less than CNY 15,000 | 348 (22.00%) |

| CNY 15,000–30,000 | 608 (38.43%) | |

| CNY 30,000–60,000 | 319 (20.16%) | |

| CNY 60,000–100,000 | 199 (12.58%) | |

| CNY 100,000–200,000 | 87 (5.50%) | |

| CNY 200,000 above | 22 (1.39%) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SES | 1 | −0.63 | 1.46 | |||||

| 2. MAAS | 0.12 ** | 1 | 3.12 | 0.86 | ||||

| 3. PSS | −0.10 ** | −0.48 ** | 1 | 1.99 | 0.52 | |||

| 4. Anxiety | −0.08 ** | −0.40 ** | 0.52 ** | 1 | 1.90 | 0.37 | ||

| 5. Depression | −0.09 ** | −0.49 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.68 ** | 1 | 1.98 | 0.52 | |

| 6. EP | −0.15 ** | −0.65 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.53 ** | 1 | 2.53 | 0.66 |

| Outcome | Predictor Variable | R | R2 | F (df) | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait Mindfulness | 0.12 | 0.02 | 24.42 (1, 1581) | |||

| SES | 0.07 | 4.94 *** | ||||

| Perceived Stress | 0.49 | 0.24 | 243.40 (2, 1580) | |||

| MAAS | −0.29 | −21.58 *** | ||||

| SES | −0.01 | −1.89 | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.55 | 0.30 | 223.84 (3, 1579) | |||

| MAAS | −0.08 | −8.00 *** | ||||

| PSS | 0.30 | 17.61 *** | ||||

| SES | −0.002 | −0.46 | ||||

| Depression | 0.66 | 0.44 | 416.82 (3, 1579) | |||

| MAAS | −0.15 | −11.48 *** | ||||

| PSS | 0.51 | 23.59 *** | ||||

| SES | −0.004 | −0.58 | ||||

| Externalizing Problems | 0.68 | 0.47 | 465.06 (3, 1579) | |||

| MAAS | −0.40 | −24.86 *** | ||||

| PSS | 0.31 | 11.55 *** | ||||

| SES | −0.03 | −3.35 *** |

| Dependent Variable | Path | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Direct Effect | −0.003 | 0.005 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Total Indirect Effect | −0.02 | 0.002 | −0.02 | −0.01 | |

| SES→MAAS→Anxiety | −0.01 | 0.002 | −0.01 | −0.003 | |

| SES→MAAS→PSS→Anxiety | −0.01 | 0.001 | −0.01 | −0.004 | |

| SES→PSS→Anxiety | −0.005 | 0.002 | −0.01 | −0.004 | |

| Depression | Direct Effect | −0.004 | 0.007 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Total Indirect Effect | −0.03 | 0.006 | −0.04 | −0.02 | |

| SES→MAAS→Depression | −0.01 | 0.002 | −0.02 | −0.01 | |

| SES→MAAS→PSS→Depression | −0.01 | 0.002 | −0.02 | −0.01 | |

| SES→MAAS→Depression | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.001 | |

| Externalizing Problems | Direct Effect | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| Total Indirect Effect | −0.04 | 0.008 | −0.06 | −0.03 | |

| SES→MAAS→EP | −0.03 | 0.006 | −0.13 | −0.08 | |

| SES→MAAS→PSS→EP | −0.01 | 0.003 | −0.01 | 0.003 | |

| SES→MAAS→EP | −0.005 | 0.002 | −0.01 | −0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, Y.; Zhou, A.; Kang, M. Family Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Trait Mindfulness and Perceived Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021625

Yuan Y, Zhou A, Kang M. Family Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Trait Mindfulness and Perceived Stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021625

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Yue, Aibao Zhou, and Manying Kang. 2023. "Family Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Trait Mindfulness and Perceived Stress" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021625

APA StyleYuan, Y., Zhou, A., & Kang, M. (2023). Family Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Trait Mindfulness and Perceived Stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021625