The Right to Sexuality, Reproductive Health, and Found a Family for People with Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

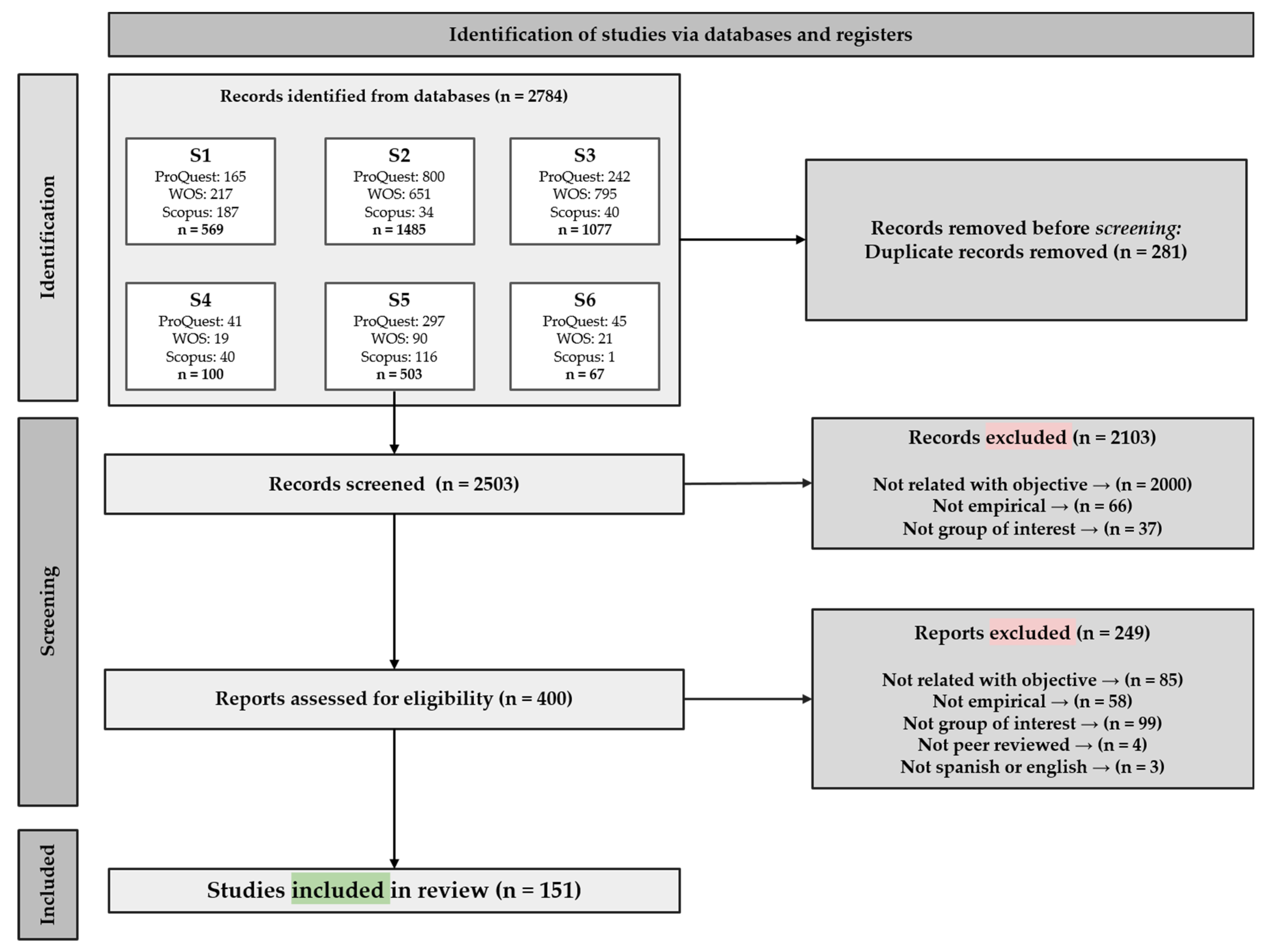

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Reviewed Studies

3.2. Attitudes toward the Sexuality of People with ID

3.2.1. Attitudes toward Sexual Freedom

3.2.2. Attitudes toward Sexuality

3.2.3. Attitudes toward Marriage

3.2.4. Attitudes toward Sterilization

3.2.5. Attitudes toward Parenthood

3.3. Intimate Relationships

3.3.1. Desires and Expectations

3.3.2. Barriers and Facilitators

3.3.3. Marriage

3.3.4. Violence and Abuse

3.4. Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH)

3.4.1. Barriers and Facilitators

Barriers and Facilitators Encountered by People with ID

3.4.2. Menstrual Health Management (MHM)

3.4.3. Contraceptive Choices

3.4.4. Sterilization

3.4.5. HIV and STIs

3.5. Sexuality and Sex Education

3.5.1. Knowledge

3.5.2. Barriers and Facilitators

3.5.3. Sexual Intercourse Experiences

3.5.4. Interventions

3.6. Pregnancy

3.6.1. Profile of Pregnant Women with ID

3.6.2. Health Conditions before, during, and after Pregnancy

3.6.3. Birth Outcomes

3.6.4. Barriers and Facilitators

3.7. Experiencing Parenthood

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Gómez, L.E.; Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A. A new paradigm in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities: Characteristics and evaluation. Psicothema 2021, 33, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, L.E.; Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A. A Quality of Life Supports Model: Six research-focused steps to evaluate the model and enhance research practices in the field of IDD. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 119, 104112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdugo, M.Á.; Schalock, R.L.; Gómez, L.E. The Quality of Life Supports Model: Twenty-five years of parallel paths have come together. Siglo Cero 2021, 52, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Sexual Health, Human Rights and the Law. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/175556/9789241564984_eng.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Murillo, I. Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos (DSR) de las Mujeres con Discapacidad [Sexual and Reproductive Rights (SRHR) of Women with Disabilities]. In Proceedings of the Jornadas Derechos de las Mujeres con Discapacidad y Agenda 2030, Madrid, Spain, 24–25 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Sustainable Development Goals: Health Targets. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/librariesprovider2/default-document-library/disability-sdg-factsheet.pdf?sfvrsn=9298b56c_8&download=true (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Lombardi, M.; Vandenbussche, H.; Claes, C.; Schalock, R.L.; De Maeyer, J.; Vandevelde. The concept of quality of life as framework for implementing the UNCRPD. J. Policy Pr. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 16, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.E.; Morán, M.L.; Navas, P.; Verdugo, M.A.; Schalock, R.L.; Lombardi, M.; Vicente, E.; Guillén, V.M.; Balboni, G.; Swerts, C.; et al. Using the quality of life framework to operationalize and assess CRPD Articles and Sustainable Development Goals. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2022; to be submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, L.E.; Morán, L.; Al-Halabí, S.; Swerts, C.; Verdugo, M.A.; Schalock, R.L. Quality of life and the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Consensus indicators for assessment. Psicothema 2022, 34, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A. Quality of Life for Human Service Practitioners; American Association on Mental Retardation: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jenaro, C.; Verdugo, M.A.; Caballo, C.; Balboni, G.; Lachapelle, Y.; Otrebski, W.; Schalock, R.L. Cross-cultural study of person-centered quality of life domains and indicators. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A.; Jenaro, C. Examining the factor structure and hierarchical nature of the quality of life construct. AJIDD-AM J. Intellect. 2010, 115, 218–233.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Trigt, P. Equal reproduction rights? The right to found a family in United Nations’ disability policy since the 1970s. Hist. Fam. 2020, 25, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, J. Capabilities, reproductive health and well-being. J. Dev. Stud. 2006, 42, 1158–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.E. #Rights4MeToo: Formación, evaluación e intervención sobre la Convención Internacional de Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad [#Rights4MeToo: Training, assessment and intervention on the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities]. + Calidad 2021, 25, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schalock, R.L.; Luckasson, R.; Tassé, M.J. The contemporary view of intellectual and developmental disabilities: Implications for psychologists. Psicothema 2019, 31, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, L.; Morán, L.; Gómez, L.E. Evaluación de resultados personales relacionados con derechos en jóvenes con discapacidad intelectual y TEA [Assessment of rights-related personal outcomes in young people with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder]. Siglo Cero 2021, 52, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, N71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornman, J.; Rathbone, L.A. Sexuality and relationship training program for women with intellectual disabilities: A social story approach. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, L.; Stinson, J.; Dotson, L.A. Staff values regarding the sexual expression of women with developmental disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2001, 19, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffew, A.; Coughlan, B.; Burke, T.; Rogers, E. Staff member’s views and attitudes to supporting people with an intellectual disability: A multi-method investigation of intimate relationships and sexuality. J. App. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 35, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, L.; Chambers, B. Intellectual disability and sexuality: Attitudes of disability support staff and leisure industry employees. J. Intellec. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 35, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, L.; Malcolm, L. “Best for everyone concerned” or “Only as a last resort”? Views of Australian doctors about sterilisation of men and women with intellectual disability. J. Intellec. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 39, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.K.; Binger, T.E.; McKenzie, C.R.; Ramcharan, P.; Nankervis, K. Sexuality, pregnancy and midwifery care for women with intellectual disabilities: A pilot study on attitudes of university students. Contemp. Nurse 2010, 35, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.; Clawson, R.; Patterson, A.; Fyson, R.; Khan, L. Risk of forced marriage amongst people with learning disabilities in the UK: Perspectives of South Asian carers. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, G.E.M.; Ramirez, E.O.L.; Esterle, M.; Sastre, M.T.M.; Mullet, E. Judging the acceptability of sexual intercourse among people with learning disabilities: A Mexico-France comparison. Sex. Disabil. 2010, 28, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, G.E.; Lopez, E.O.; Mullet, E. Acceptability of sexual relationships among people with learning disabilities: Family and professional caregivers’ views in Mexico. Sex. Disabil. 2011, 29, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muswera, T.; Kasiram, M. Understanding the sexuality of persons with intellectual disability in residential facilities: Perceptions of service providers and people with disabilities. Soc. Work 2019, 55, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajot, E.; Muñoz, M.T.; Nacher, M. Mapping people’s views regarding childbearing among people with learning difficulties. Sex. Disabil. 2015, 33, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchomiuk, M. Specialists and sexuality of individuals with disability. Sex. Disabil. 2012, 30, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchomiuk, M. Model of intellectual disability and the relationship of attitudes towards the sexuality of persons with an intellectual disability. Sex. Disabil. 2013, 31, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pownall, J.D.; Jahoda, A.; Hastings, R.P. Sexuality and sex education of adolescents with intellectual disability: Mothers’ attitudes, experiences, and support needs. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 50, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, Z.; Ebadi, A.; Farmahini, M. Marriage challenges of women with intellectual disability in Iran: A qualitative study. Sex. Disabil. 2020, 38, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickström, M.; Larsson, M.; Höglund, B. How can sexual and reproductive health and rights be enhanced for young people with intellectual disability?—Focus group interviews with staff in Sweden. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winarni, T.I.; Hardian, H.; Suharta, S.; Ediati, A. Attitudes towards sexuality in males and females with intellectual disabilities: Indonesia setting. J. Intellect. Disabil.-Diagn. Treat. 2018, 6, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bane, G.; Deely, M.; Donohoe, B.; Dooher, M.; Flaherty, J.; Garcia-Iriarte, E.; Hopkins, R.; Mahon, A.; Minogue, G.; McDonagh, P.; et al. Relationships of people with learning disabilities in Ireland. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2012, 40, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C.; Terry, L.; Popple, K. Partner selection for people with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 30, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C.; Terry, L.; Popple, K. The importance of romantic love to people with learning disabilities. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2017, 45, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnachie, M.; Jones, B.; Jahoda, A. Facial attraction: An exploratory study of the judgements made by people with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 65, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbers, S.A.; Hendriks, L.; Jahoda, A.; Hastings, R.P.; Embregts, P.J. Living with support: Experiences of people with mild intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, J.; Määttä, K.; Uusiautti, S. ‘Everyone needs love’–an interview study about perceptions of love in people with intellectual disability (ID). Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2017, 22, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, A.; Frawley, P. Gender, sexuality and relationships for young Australian women with intellectual disability. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 654–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, D.; Burns, J. What’s love got to do with it?: Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, and bisexual people with intellectual disabilities in the united kingdom and views of the staff who support them. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2007, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C.; McCarthy, M.; Milne, K.; Elson, N.; Forrester-Jones, R.; Hunt, S. “Always trying to walk a bit of a tightrope”: The role of social care staff in supporting adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities to develop and maintain loving relationships. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2020, 48, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C.; McCarthy, M.; Skillman, K.M.; Elson, N.; Hunt, S.; Forrester-Jones, R. ‘She misses the subtleties and I have to help–help to make the invisible visible’: Parents’ role in supporting adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities with intimate relationships. Int. J. Care Caring 2021, 5, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C.; Terry, L.; Popple, K. Supporting people with learning disabilities to make and maintain intimate relationships. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2017, 22, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callus, A.M.; Bonello, I.; Mifsud, C.; Fenech, R. Overprotection in the lives of people with intellectual disability in Malta: Knowing what is control and what is enabling support. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 34, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cytowska, B.; Zierkiewicz, E. Conversations about health–Sharing the personal experiences of women with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, J.; Reynolds, L.; Ellison, C.; Bellon, M. Let’s talk about sex: How people with intellectual disability in Australia engage with online social media and intimate relationships. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2017, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, C. The COVID-19 pandemic and quality of life outcomes of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, J.; Combes, H.; Richards, R. Exploring how support workers understand their role in supporting adults with intellectual disabilities to access the Internet for intimate relationships. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, M.; Milne, K.; Elson, N.; Bates, C.; Forrester-Jones, R.; Hunt, S. Making connections and building confidence: A study of specialist dating agencies for people with intellectual disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2020, 38, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, A.; Georgi-Tscherry, P.; Berger, F.; Studer, M. Participation of adults with cognitive, physical, or psychiatric impairments in family of origin and intimate relationships: A grounded theory study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retznik, L.; Wienholz, S.; Höltermann, A.; Conrad, I.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Young people with intellectual disability and their experiences with intimate relationships: A follow-up analysis of parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives. Sex. Disabil. 2022, 40, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, D.; Kok, G.; Stoffelen, J.M.T.; Curfs, L.M.G. People with Intellectual disabilities talk about sexuality: Implications for the development of sex education. Sex. Disabil. 2017, 35, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clawson, R. Safeguarding people with learning disabilities from forced marriage: The role of Safeguarding Adult Boards. J. Adult Prot. 2016, 18, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clawson, R.; Patterson, A.; Fyson, R.; McCarthy, M. The demographics of forced marriage of people with learning disabilities: Findings from a national database. J. Adult Prot. 2020, 22, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.; Bowring, D.L.; Hatton, C. Not such an ordinary life: A comparison of employment, marital status and housing profiles of adults with and without intellectual disabilities. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2019, 24, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Ye, J. Sexuality and marriage of women with intellectual disability in male-squeezed rural China. Sex. Disabil. 2012, 30, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, A.; McConnell, D. The marital status of disabled women in Canada: A population-based analysis. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2016, 18, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsdóttir, K.; Stefánsdóttir, Á.; Stefánsdóttir, G.V. People with intellectual disabilities negotiate autonomy, gender and sexuality. Sex. Disabil. 2017, 35, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malihi, Z.A.; Fanslow, J.L.; Hashemi, L.; Gulliver, P.J.; McIntosh, T.K. Prevalence of non-partner physical and sexual violence against people with disabilities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.A.; MacMullin, J.; Waechter, R.; Wekerle, C.; The MAP Research Team. Child Maltreatment, adolescent attachment style, and dating violence: Considerations in youths with borderline-to-mild intellectual disability. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2011, 9, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.M.; Atkinson, J.P.; Smith, C.A.; Windsor, R. A friendship and dating program for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A formative evaluation. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 51, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaronnik, N.; Pendo, E.; Lagu, T.; DeJong, C.; Perez-Caraballo, A.; Iezzoni, L.I. Ensuring the reproductive rights of women with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 45, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, E.; Kroese, B.S. Midwives’ experiences of caring for women with learning disabilities–a qualitative study. Midwifery 2016, 36, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabb, C.; Owen, R.; Heller, T. Female medicaid enrollees with disabilities and discussions with health care providers about contraception/family planning and sexually transmitted infections. Sex. Disabil. 2020, 38, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, H.P.; Smith, J.D.; Friedman, E. Family planning services for persons handicapped by mental retardation. Am. J Public Health 1976, 66, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotson, L.A.; Stinson, J.; Christian, L. People tell me I can’t have sex: Women with disabilities share their personal perspectives on health care, sexuality, and reproductive rights. Women Ther. 2003, 26, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglund, B.; Larsson, M. Midwives’ work and attitudes towards contraceptive counselling and contraception among women with intellectual disability: Focus group interviews in Sweden. Eur. J. Contracep. Reprod. Health Care 2019, 24, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.M.; Taylor, L.C.; Davis, M.M. Primary care for adults with Down syndrome: Adherence to preventive healthcare recommendations. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2013, 57, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Devine, A.; Marco, M.; Zayas, J.; Gill-Atkinson, L.; Vaughan, C. Sexual and reproductive health services for women with disability: A qualitative study with service providers in the Philippines. BMC Women Health 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.P.; Lin, J.D.; Sung, C.L.; Liu, T.W.; Liu, Y.L.; Chen, L.M.; Chu, C.M. Papanicolaou smear screening of women with intellectual disabilities: A cross-sectional survey in Taiwan. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 31, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.P.; Lin, P.Y.; Hsu, S.W.; Loh, C.H.; Lin, J.D.; Lai, C.I.; Chien, W.C.; Lin, F.G. Caregiver awareness of reproductive health issues for women with intellectual disabilities. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac-Seing, M.; Zinszer, K.; Eryong, B.; Ajok, E.; Ferlatte, O.; Zarowsky, C. The intersectional jeopardy of disability, gender and sexual and reproductive health: Experiences and recommendations of women and men with disabilities in Northern Uganda. Sex. Reprod. Health Matt. 2020, 28, 1772654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesiäislehto, V.; Katsui, H.; Sambaiga, R. Disparities in accessing sexual and reproductive health services at the intersection of disability and female adolescence in Tanzania. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. Health 2021, 18, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, S.L.; Son, E.; Powell, R.M.; Igdalsky, L. Reproductive cancer treatment hospitalizations of US women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwakoti, R.; Gurung, Y.B.; Poudel, R.C.; Neupane, S.; Thapa, R.K.; Deuja, S.; Pathak, R.S. Factors affecting utilization of sexual and reproductive health services among women with disabilities- a mixed-method cross-sectional study from Ilam district, Nepal. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumskiene, E.; Orlova, U.L. Sexuality of dehumanized people across post-soviet countries: Patterns from closed residential care institutions in Lithuania. Sex. Cult. 2015, 19, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, M.; Nagujjah, Y.; Rimal, N.; Bukania, F.; Krause, S. Intersecting sexual and reproductive health and disability in humanitarian settings: Risks, needs, and capacities of refugees with disabilities in Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda. Sex. Disabil. 2015, 33, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taouk, L.H.; Fialkow, M.F.; Schulkin, J.A. Provision of reproductive healthcare to women with disabilities: A survey of obstetrician–gynecologists’ training, practices, and perceived barriers. Health Equity 2018, 2, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, K.; Casson, K.; Fleming, P.; Dobbs, F.; Parahoo, K.; Armstrong, J. Sexual health promotion in primary care–activities and views of general practitioners and practice nurses. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2008, 9, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, P.; Ferrie, J. Reproductive (in)justice and inequality in the lives of women with intellectual disabilities in Scotland. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2020, 22, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, S.; Carey, G.; Hargrave, J.; Malbon, E.; Green, C. Women’s experiences of accessing individualized disability supports: Gender inequality and Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, S.M.; Kung, P.T.; Tsai, W.C. The characteristics and relevant factors of Pap smear test use for women with intellectual disabilities in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goli, S.; Noroozi, M.; Salehi, M. Parental experiences about the sexual and reproductive health of adolescent girls with intellectual disability: A qualitative study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2020, 25, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, J.; Carlson, G.; Taylor, M.; Wilson, J. Menstrual management and intellectual disability: New perspectives. Occupat. Ther. Int. 1994, 1, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.A.; Joshi, P.G. Study of menstrual patterns in adolescent girls with disabilities in a residential institution. Int. J. Adol. Med. Health. 2015, 27, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikayini, S.; Arun, S. Challenges faced by primary caretakers of adolescent girls with intellectual disability during their menstrual cycle in Puducherry: A mixed method study. Indian J. Comm. Med. 2021, 46, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkhairulnisa, A.I.; Chew, K.T.; Zainudin, A.A.; Lim, P.S.; Shafiee, M.N.; Kampan, N.; Ismail, W.S.W.; Grover, S.; Nur-Azurah, A.G. Management of menstrual disorder in adolescent girls with intellectual disabilities: A blessing or a curse? Obs. Gynecol. Int. 2018, 11, 9795681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikora, T.J.; Bourke, J.; Bathgate, K.; Foley, K.R.; Lennox, N.; Leonard, H. Health conditions and their impact among adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome. PloS ONE 2014, 9, e96868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, J.; Kayastha, S.; Mahon, T.; Torondel, B.; Hameed, S.; Sigdel, A.; Gyawali, A.; Kuper, H. Qualitative study exploring the barriers to menstrual hygiene management faced by adolescents and young people with a disability, and their carers in the Kavrepalanchok district, Nepal. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, J.; Mahon, T.; Torondel, B.; Hameed, S.; Kuper, H. Feasibility study of a menstrual hygiene management intervention for people with intellectual impairments and their carers in Nepal. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, S.; Earle, S.; Tilley, E.; Walmsley, J. Contraceptive decision-making and women with learning disabilities. Sexualities 2016, 19, 698–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. ‘I have the jab so I can’t be blamed for getting pregnant’: Contraception and women with learning disabilities. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum. 2009, 32, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. Prescribing contraception to women with intellectual disabilities: General practitioners’ attitudes and practices. Sex. Disabil. 2011, 29, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, L. Clinical conundrum: What would you do? Reproductive issues and learning disability: Different perspectives of professionals and parents. J. Fam. Plann. Reprod. Health Care 2004, 30, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, B.I.; Alexander, M.; Breech, L.L. Intrauterine device use in adolescents with disabilities. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walmsley, J.; Earle, S.; Tilley, E.; Ledger, S.; Chapman, R.; Townson, L. The experiences of women with learning disabilities on contraception choice. Prim. Health Care 2016, 26, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Mitra, M.; Parish, S.L.; Reddy, G.K.M. Provision of moderately and highly effective reversible contraception to insured women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Obs. Gynec. 2018, 132, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C. Sterilization and intellectually disabled people in New Zealand: Rights, responsibility and wise counsel needed. Kotuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2015, 10, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Mitra, M.; Wu, J.P.; Parish, S.L.; Valentine, A.; Dembo, R.S. Female sterilization and cognitive disability in the United States, 2011–2015. Obs. Gynec. 2018, 132, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez-González, H.; Valdez-Martínez, E. Legitimacy of hysterectomy to solve the “problem” of menstrual hygiene in adolescents with intellectual disability. Gac Med Mex 2018, 154, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-González, H.; Valdez-Martínez, E.; Bedolla, M. Clinical, epidemiologic and ethical aspects of hysterectomy in young females with intellectual disability: A multi-centre study of public hospitals in Mexico City. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 746399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderemi, T.J.; Mac-Seing, M.; Woreta, S.A.; Mati, K.A. Predictors of voluntary HIV counselling and testing services utilization among people with disabilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. AIDS Care 2014, 26, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderemi, T.J.; Pillay, B.J.; Esterhuizen, T.M. Differences in HIV knowledge and sexual practices of learners with intellectual disabilities and non-disabled learners in Nigeria. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 17331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenk, K.D.; Tun, W.; Sheehy, M.; Okal, J.; Kuffour, E.; Moono, G.; Mutale, F.; Kyeremaa, R.; Ngirabakunzi, E.; Amanyeiwe, U.; et al. “Even the fowl has feelings”: Access to HIV information and services among persons with disabilities in Ghana, Uganda, and Zambia. Disabil. Rehab. 2020, 42, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, E.K.; Hand, B.N.; Simpson, K.N.; Darragh, A.R. Sexually transmitted infections in privately insured adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2019, 8, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkić-Jovanović, N.; Runjo, V.; Tamaš, D.; Slavković, S.; Milankov, V. Persons with intellectual disability: Sexual behaviour, knowledge and assertiveness. Slov. J. Public Health 2021, 60, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frawley, P.; Wilson, N.J. Young people with intellectual disability talking about sexuality education and information. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isler, A.; Beytut, D.; Tas, F.; Conk, Z. A study on sexuality with the parents of adolescents with intellectual disability. Sex. Disabil. 2009, 27, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isler, A.; Tas, F.; Beytut, D.; Conk, Z. Sexuality in adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2009, 27, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, A.O.; Anoemuah, O.A.; Ladipo, O.A.; Delano, G.E.; Idowu, G.F. Sexual behaviours and reproductive health knowledge among in-school young people with disabilities in Ibadan, Nigeria. Health Educ. 2007, 107, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pownall, J.; Wilson, S.; Jahoda, A. Health knowledge and the impact of social exclusion on young people with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, V.R.; Stancliffe, R.J.; Wilson, N.J.; Broom, A. The content, usefulness and usability of sexual knowledge assessment tools for people with intellectual disability. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgin-Büyükbayraktar, Ç.; Konuk-Er, R.; Kesici, S. According to the opinions of teachers of individuals with intellectual disabilities: What are the sexual problems of students with special education needs? How should sexual education be provided for them? J. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gürol, A.M.; Polat, S.; Oran, T. Views of mothers having children with intellectual disability regarding sexual education: A qualitative study. Sex. Disabil. 2014, 32, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanass-Hancock, J.; Nene, S.; Johns, R.; Chappell, P. The Impact of contextual factors on comprehensive sexuality education for learners with intellectual disabilities in South Africa. Sex. Disabil. 2018, 36, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfgren-Mårtenson, L. The invisibility of young homosexual women and men with intellectual disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2009, 27, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, P.; Sivakami, M. Exploring parental perceptions and concerns about sexuality and reproductive health of their child with intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) in Mumbai. Front. Sociol. 2019, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.; Lincoln, S.; Meredith, S.; Cross, E.M.; Rintell, D. Sex education and intellectual disability: Practices and insight from pediatric genetic counselors. J. Genet. Couns. 2016, 25, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.; Odberg, K.; Emmelin, M. Experiences of teaching sexual and reproductive health to students with intellectual disabilities. Sex Educ. 2020, 20, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, P. ‘I count myself as normal, well, not normal, but normal enough’ Men with learning disabilities tell their stories about sexuality and sexual identity. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2007, 12, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, S.; Emerson, E.; Robertson, J.; Hatton, C. Sexual activity and sexual health among young adults with and without mild/moderate intellectual disability. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.M.; Udry, J.R. Sexual experiences of adolescents with low cognitive abilities in the U.S. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2005, 17, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandra, C.L.; Chowdhury, A.R. The first sexual experience among adolescent girls with and without disabilities. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandra, C.L.; Shameem, M.; Ghori, S.J. Disability and the context of boys’ first sexual intercourse. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, M.; Shawe, J. The experiences of adults with learning disabilities attending a sexuality and relationship group: “I want to get married and have kids”. J. Fam. Plann. Reprod. Health Care 2014, 40, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Mello, R.R.; Soler-Gallart, M.; Braga, F.M.; Natividad-Sancho, L. Dialogic feminist gathering and the prevention of gender violence in girls with intellectual disabilities. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 662241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goli, S.; Noroozi, M.; Salehi, M. Comparing the effect of two educational interventions on mothers’ awareness, attitude, and self-efficacy regarding sexual health care of educable intellectually disabled adolescent girls: A cluster randomized control trial. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Bermejo, B.; Flores, N.; Amor, P.J.; Jenaro, C. Evidences of an implemented training program in consensual and responsible sexual relations for people with intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randell, E.; Janeslätt, G.; Höglund, B. A school-based intervention can promote insights into future parenting in students with intellectual disabilities—A Swedish interview study. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akobirshoev, I.; Mitra, M.; Parish, S.L.; Moore Simas, T.A.; Dembo, R.; Ncube, C.N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes and labour and delivery-related charges among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akobirshoev, I.; Parish, S.L.; Mitra, M.; Rosenthal, E. Birth outcomes among US women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2017, 10, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, E.E.; Powell, R.M.; Ayers, K.B. Experiences of breastfeeding among disabled women. Women Health Issues 2021, 31, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacharach, V.R.; Baumeister, A.A. Direct and indirect effects of maternal intelligence, maternal age, income, and home environment on intelligence of preterm, low-birth-weight children. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 1998, 19, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, F.; Darney, B.; Caughey, A.; Horner-Johnson, W. Medical indications for primary cesarean delivery in women with and without disabilities. J. Matern. -Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 3391–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Breckenridge, J.P.; Devaney, J.; Kroll, T.; Lazenbatt, A.; Taylor, J. Disabled women’s experiences of accessing and utilising maternity services when they are affected by domestic abuse: A critical incident technique study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.K.; Cobigo, V.; Lunsky, Y.; Vigod, S. Reproductive health in women with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Ontario: Implications for policy and practice. Healthc. Q. 2019, 21, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.K.; Cobigo, V.; Lunsky, Y.; Dennis, C.L.; Vigod, S. Perinatal health of women with intellectual and developmental disabilities and comorbid mental illness. Can. J. Psych. 2016, 61, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.K.; Kirkham, Y.A.; Cobigo, V.; Lunsky, Y.; Vigod, S.N. Labour and delivery interventions in women with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A population-based cohort study. J. Epid. Comm. Health 2016, 70, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.K.; Potvin, L.A.; Lunsky, Y.; Vigod, S.N. Maternal intellectual or developmental disability and newborn discharge to protective services. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20181416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.K.; Ray, J.G.; Liu, N.; Lunsky, Y.; Vigod, S.N. Rapid repeat pregnancy among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A population-based cohort study. Cmaj 2018, 190, E949–E956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, K.M.; Mitra, M.; Zhang, J.; Parish, S.L. Postpartum health care among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darney, B.G.; Biel, F.M.; Quigley, B.P.; Caughey, A.B.; Horner-Johnson, W. Primary cesarean delivery patterns among women with physical, sensory, or intellectual disabilities. Women Health Issues 2017, 27, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskin, K.; James, H. Using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale with learning disabled mothers. Commun. Practit. 2006, 79, 392. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, J.L.; Grewal, J.; Chen, Z.; Cernich, A.N.; Grantz, K.L. Risk of adverse maternal outcomes in pregnant women with disabilities. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2138414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.; Martinez, V. Associations between disability and infertility among US reproductive-aged women. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höglund, B.; Lindgren, P.; Larsson, M. Pregnancy and birth outcomes of women with intellectual disability in Sweden: A national register study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höglund, B.; Lindgren, P.; Larsson, M. Newborns of mothers with intellectual disability have a higher risk of perinatal death and being small for gestational age. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner-Johnson, W.; Biel, F.M.; Caughey, A.B.; Darney, B.G. Differences in prenatal care by presence and type of maternal disability. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouf, R.; Henderson, J.; Redshaw, M. Access and quality of maternity care for disabled women during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period in England: Data from a national survey. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouf, R.; McLeish, J.; Ryan, S.; Gray, R.; Redshaw, M. ‘We both just wanted to be normal parents’: A qualitative study of the experience of maternity care for women with learning disability. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Akobirshoev, I.; Parish, S.L.; Valentine, A.; Clements, K.M.; Simas, T.A.M. Postpartum emergency department use among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A retrospective cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Comm. Health 2019, 73, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Parish, S.L.; Akobirshoev, I.; Rosenthal, E.; Simas, T.A.M. Postpartum Hospital Utilization among Massachusetts Women with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Parish, S.L.; Clements, K.M.; Zhang, J.; Simas, T.A.M. Antenatal hospitalization among US women with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A retrospective cohort study. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 123, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, B.A.; Crane, D.; Doody, D.R.; Stuart, S.N.; Schiff, M.A. Pregnancy course, infant outcomes, rehospitalization, and mortality among women with intellectual disability. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, G.V.S.; John, N.; Sagar, J. Reproductive health of women with and without disabilities in South India, the SIDE study (South India Disability Evidence) study: A case control study. BMC Women Health 2014, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, S.L.; Mitra, M.; Son, E.; Bonardi, A.; Swoboda, P.T.; Igdalsky, L. Pregnancy outcomes among US women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 120, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, L.A.; Lindenbach, R.D.; Brown, H.K.; Cobigo, V. Preparing for motherhood: Women with intellectual disabilities on informational support received during pregnancy and knowledge about childbearing. J. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Redshaw, M.; Malouf, R.; Gao, H.; Gray, R. Women with disability: The experience of maternity care during pregnancy, labour and birth and the postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, E.; Ehrenthal, D.B.; Mallinson, D.C.; Bishop, L.; Kuo, H.H.; Durkin, M. Pregnancy complications and maternal birth outcomes in women with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Wisconsin Medicaid. PloS ONE 2020, 15, e0241298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.E.; Cho, G.J.; Bak, S.; Won, S.E.; Han, S.W.; Bin Lee, S.; Oh, M.J.; Kim, S.J. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of women with disabilities: A nationwide population-based study in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasoff, L.A.; Lunsky, Y.; Chen, S.; Guttmann, A.; Havercamp, S.M.; Parish, S.L.; Vigod, S.N.; Carty, A.; Brown, H.K. Preconception health characteristics of women with disabilities in Ontario: A population-based, cross-sectional study. J. Women’s Health 2020, 29, 1564–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickström, M.; Höglund, B.; Larsson, M.; Lundgren, M. Increased risk for mental illness, injuries, and violence in children born to mothers with intellectual disability: A register study in Sweden during 1999–2012. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 65, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, S.; Strnadová, I.; Loblinzk, J.; Danker, J. Benefits and limits of peer support for mothers with intellectual disability affected by domestic violence and child protection. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. ‘All I wanted was a happy life’: The struggles of women with learning disabilities to raise their children while also experiencing domestic violence. J. Gender-Based Viol. 2019, 3, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, J.; Abbott, D.; Dugdale, D. “Someone will come in and say I’m doing it wrong.” The perspectives of fathers with learning disabilities in England. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2021, 49, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiber, I.; Tengland, P.A.; Berglund, J.S.; Eklund, M. Everyday life when growing up with a mother with an intellectual or developmental disability: Four retrospective life-stories. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 27, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuskelly, M.; Bryde, R. Attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with an intellectual disability: Parents, support staff, and a community sample. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2004, 29, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterle, M.; Muñoz Sastre, M.T.; Mullet, E. Judging the Acceptability of Sexual Intercourse Among People with Learning Disabilities: French Laypeople’s Viewpoint. Sex. Disabil. 2008, 26, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsdóttir, K. Resisting the Reflection: Identity in Inclusive Life History Research. DSQ 2010, 30, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. Sexual Rights: An IPPF Declaration. Available online: https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/sexualrightsippfdeclaration_1.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- MacLachlan, M.; Mannan, H.; Huss, T.; Munthali, A.; Amin, M. Policies and processes for social inclusion: Using EquiFrame and EquIPP for policy dialogue: Comment on “Are sexual and reproductive health policies designed for all? Vulnerable groups in policy documents of four European countries and their involvement in policy development”. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2016, 5, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, R.; Llewellyn, G. Mothering differently: Narratives of mothers with intellectual disability whose children have been compulsorily removed. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 37, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.; Strnadová, I.; Watfern, C.; Pebdani, R.; Bateson, D.; Loblinzk, J.; Guy, R.; Newman, C. The sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people with intellectual disability: A scoping review. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 19, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asselt-Goverts, A.E.; Embregts, P.J.C.M.; Hendriks, A.H.C. Structural and functional characteristics of the social networks of people with mild intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegerink, D.J.; Stam, H.J.; Ketelaar, M.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Roebroeck, M.E.; Transition Research Group South West Netherlands. Personal and environmental factors contributing to participation in romantic relationships and sexual activity of young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 1481–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, E.; Wacker, J.; Macy, R.; Parish, S. Sexual assault prevention for women with intellectual disabilities: A critical review of the evidence. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 47, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beber, E.; Biswas, A.B. Marriage and family life in people with developmental disability. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 2009, 2, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.M. Prevalence of sexual abuse of people with intellectual disabilities in Taiwan. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2007, 45, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastgate, G. Sex and intellectual disability: Dealing with sexual health issues. Aust. Fam. Physician 2011, 40, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gott, M.; Galena, E.; Hinchliff, S.; Elford, H. “Opening a can of worms”: GP and practice nurse barriers to talking about sexual health in primary care. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphery, S.; Nazareth, I. GPs’ views on their management of sexual dysfunction. Fam. Pract. 2001, 18, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, T.; Mears, J. Sexual health and the practice nurse: A survey of reported practice and attitudes. BMJ Sex. Repr. Health 2000, 26, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromaras, K.; Moskos, M.; Mahuteau, S.; Isherwood, L.; Goode, A.; Walton, H.; Smith, L.; Wei, Z.; Flavel, J. Evaluation of the NDIS. Int. J. Care Caring 2018, 2, 595–597. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, M. Exercising choice and control–women with learning disabilities and contraception. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2010, 38, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. Contraception and women with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2009, 22, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.C.; Lu, Z.Y. Deciding about sterilisation: Perspectives from women with an intellectual disability and their families in Taiwan. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, E.; Kayani, S.; Garden, A. Management of menstrual problems in adolescents with learning and physical disabilities. Obs. Gynaec. 2013, 15, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.T.; Carlson, G.M.; Van Dooren, K. Practical approaches to supporting young women with intellectual disabilities and high support needs with their menstruation. Health Care Women Int. 2012, 33, 678–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.C.; Lu, Z.Y.J. Caring for a daughter with intellectual disabilities in managing menstruation: A mother’s perspective. J Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 37, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.P.; Lin, J.D.M.; Chu, C.M.; Chen, L.M. Caregiver attitudes to gynecological health of women with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 36, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.P.; Lin, P.Y.; Chu, C.M.; Lin, J.D. Predictors of caregiver supportive behaviors towards reproductive health care for women with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, P.; Sivakami, M. Lost in transition: Menstrual experiences of intellectually disabled school-going adolescents in Delhi, India. Waterlines 2017, 36, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, J.; Torondel, B.; Hameed, S.; Mahon, T.; Kuper, H. Systematic review of menstrual hygiene management requirements, its barriers and strategies for disabled people. PloS ONE 2019, 14, e0210974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, J.; Raturi, R. The Right to Health of Persons with Disabilities in India: Access to and Non-Discrimination in Health Care for Persons with Disabilities, 1st ed.; Human Rights Law Network: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bernert, D.J. Sexuality and disability in the lives of women with intellectual disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2011, 29, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Llario, M.D.; Morell-Mengual, V.; Ballester-Arnal, R.; Díaz-Rodríguez, I. The experience of sexuality in adults with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2018, 62, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippold, T.; Burns, J. Social support and intellectual disabilities: A comparison between social networks of adults with intellectual disability and those with physical disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2009, 53, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldacre, A.D.; Gray, R.; Goldacre, M.J. Childbirth in women with intellectual disability: Characteristics of their pregnancies and outcomes in an archived epidemiological dataset. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2015, 59, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Parish, S.L.; Clements, K.M.; Cui, X.; Diop, H. Pregnancy outcomes among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am. J. Prevent. Med. 2015, 48, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, D.; Lalor, J.; Begley, C. Access to maternity services for women with a physical disability: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Childbirth 2013, 3, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilleltensky, O. A Ramp to Mothering. In Motherhood and Disability; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 152–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeltzer, S.C.; Sharts-Hopko, N.C.; Ott, B.B.; Zimmerman, V.; Duffin, J. Perspectives of women with disabilities on reaching those who are hard to reach. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2007, 39, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Breckenridge, J.P.; Devaney, J.; Duncan, F.; Kroll, T.; Lazenbatt, A.; Taylor, J. Priorities and strategies for improving disabled women’s access to maternity services when they are affected by domestic abuse: A multi-method study using concept maps. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höglund, B.; Larsson, M. Struggling for motherhood with an intellectual disability—A qualitative study of women’s experiences in Sweden. Midwifery 2013, 29, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchomiuk, M. Social context of disabled parenting. Sex. Disabil. 2014, 32, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.; Dodd, K. ‘Normal people can have a child but disability can’t’: The experiences of mothers with mild learning disabilities who have had their children removed. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2014, 42, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, R.; Llewellyn, G. What happens to parents with intellectual disability following removal of their child in child protection proceedings? J. Intellect. Devl. Disabil. 2009, 34, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarleton, B.; Ward, L.; Howarth, J. Finding the Right Support?: A Review of Issues and Positive Practice in Supporting Parents with Learning Difficulties and Their Children, 1st ed.; Baring Foundation; University of Bristol: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dewson, H.; Rix, K.J.; Le Gallez, I.; Choong, K.A. Sexual rights, mental disorder and intellectual disability: Practical implications for policy makers and practitioners. B. J. Psych. Adv. 2018, 24, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, M.Á.; Navas, P.; Gómez, L.E.; Schalock, R.L. The concept of quality of life and its role in enhancing human rights in the field of intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, L.E.; Monsalve, A.; Morán, M.L.; Alcedo, M.Á.; Lombardi, M.; Schalock, R.L. Measurable Indicators of CRPD for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities within the Quality of Life Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search 1 | intellectual disabilit* OR intellectual impairment OR mental retardation OR developmental disabilit* OR learning disabilit* OR down syndrome* OR fragile x* AND marriage OR marital OR couple OR spouse |

| Search 2 | intellectual disabilit* OR intellectual impairment OR mental retardation OR developmental disabilit* OR learning disabilit* OR down syndrome* OR fragile x* AND “family planning” OR “contraceptives methods” OR contraception OR “birth control” |

| Search 3 | intellectual disabilit* OR intellectual impairment OR mental retardation OR developmental disabilit* OR learning disabilit* OR down syndrome* OR fragile x* AND women OR woman AND maternity OR motherhood OR mother OR maternal OR mothering OR pregnancy OR pregnant OR parenthood OR parents OR parenting |

| Search 4 | intellectual disabilit* OR intellectual impairment OR mental retardation OR developmental disabilit* OR learning disabilit* OR down syndrome* OR fragile x* AND “romantic relationship” OR “close relationship” OR “intimate relationship” OR boyfriend OR girlfriend |

| Search 5 | intellectual disabilit* OR intellectual impairment OR mental retardation OR developmental disabilit* OR learning disabilit* OR down syndrome* OR fragile x* AND woman OR women AND “menstrual education” OR “menstrual support” OR “reproductive health” |

| Search 6 | intellectual disabilit* OR intellectual impairment OR mental retardation OR developmental disabilit* OR learning disabilit* OR down syndrome* OR fragile x* AND sterili* OR “forced sterili*” |

| Study design | Empirical studies: Any qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method observational study containing attitudes, interventions, and primary or secondary data analysis published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. |

| Aim of the study | Studies about issues relating to Article 23 (home and family) or Article 25 (health, specifically sexual and reproductive health) of the CRPD: This includes studies covering such diverse topics as affective, loving, or intimate relationships; marriage or living as a couple; maternity, paternity, founding a family, and bearing children; family planning, contraception, and sterilization; sexual and reproductive life; relationships and sex education. |

| Participants and sample | Two types of studies according to participants: (a) Studies whose participants were people with ID (including those with specific syndromes such as Down Syndrome or Fragile X) and studies that clearly described a subgroup with ID; and(b) Studies whose participants were family members, caregivers, or health providers of people with ID. |

| Language | Studies written in English or Spanish. |

| Theme (n Studies) | References Included in This Review (Numbers Used in the Reference List) |

|---|---|

| Attitudes (n = 17) | [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] |

| Intimate Relationships (n = 30) | [22,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] |

| Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) (n = 47) | [21,35,62,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109] |

| Sexuality and Sex Education (n = 28) | [21,33,56,62,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133] |

| Pregnancy (n = 33) | [134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166] |

| Experiencing Parenthood (n = 4) | [167,168,169,170] |

| CRPD Articles | QOL Domain Based on Verdugo et al. [214] | QOL Indicators Based on Gómez et al. [9,10] and Lombardi et al. [8] | Topics and Subtopics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 (Respect for home and the family) | Interpersonal relationships | Right to set up their own family Right to be a parent Dating and intimacy with persons of choice | Attitudes Intimate Relationships Pregnancy Sexuality and Sex Education Experiencing Parenthood |

| 25 (Health) | Physical wellbeing | Physical status Nutritional status Chronic conditions | Attitudes Toward Sterilization Sexuality and Sex Education Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) Pregnancy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Curiel, P.; Vicente, E.; Morán, M.L.; Gómez, L.E. The Right to Sexuality, Reproductive Health, and Found a Family for People with Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021587

Pérez-Curiel P, Vicente E, Morán ML, Gómez LE. The Right to Sexuality, Reproductive Health, and Found a Family for People with Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021587

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Curiel, Patricia, Eva Vicente, M. Lucía Morán, and Laura E. Gómez. 2023. "The Right to Sexuality, Reproductive Health, and Found a Family for People with Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021587

APA StylePérez-Curiel, P., Vicente, E., Morán, M. L., & Gómez, L. E. (2023). The Right to Sexuality, Reproductive Health, and Found a Family for People with Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021587