Feeling Informed and Safe Are Important Factors in the Psychosomatic Health of Frontline Workers in the Health Sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Material and Inventories

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

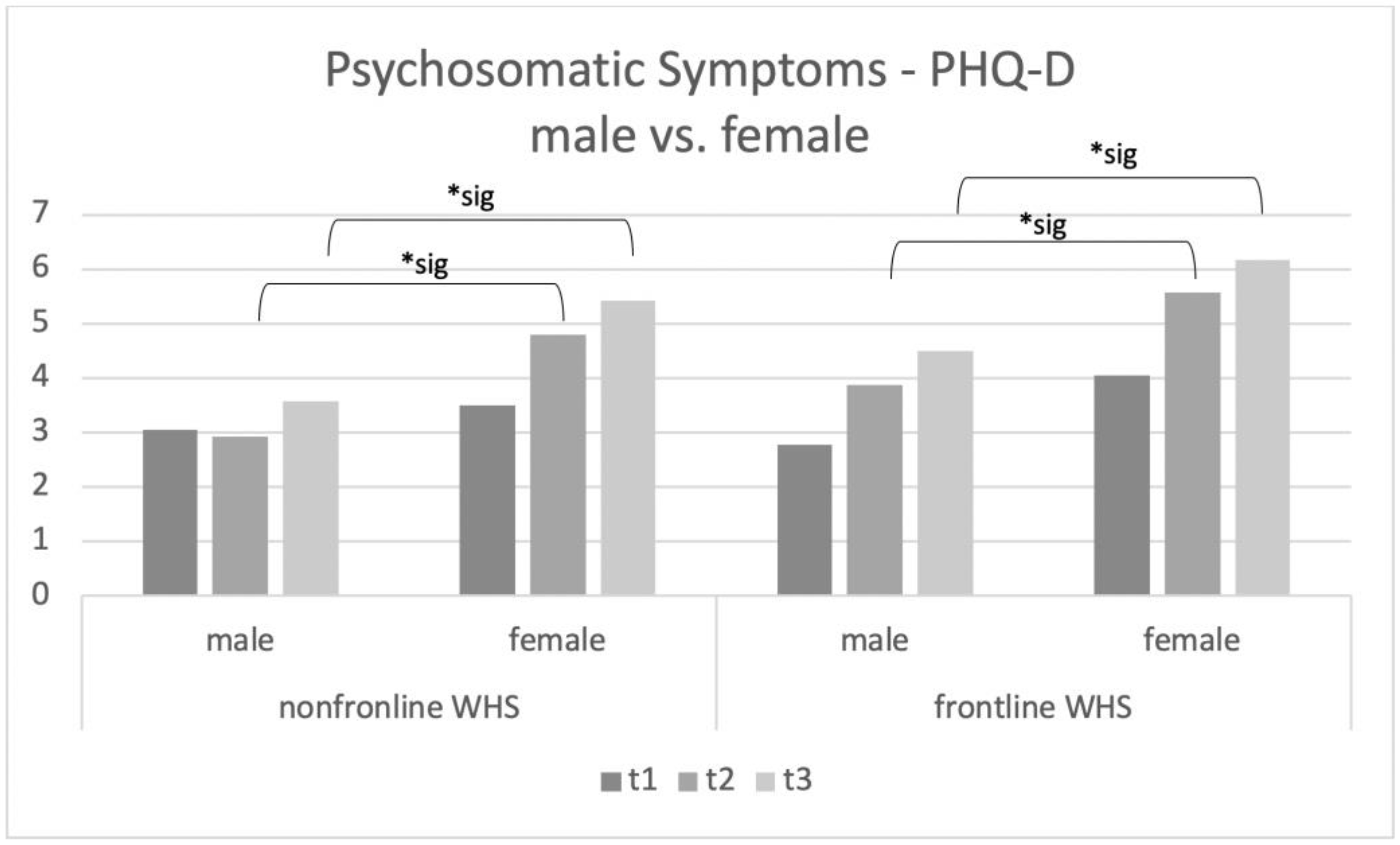

3.1.1. Psychosomatic Symptoms in Workers in the Health Sector

3.1.2. Association between COVID-19 Work-Related Fears and “Psychosomatic Symptoms”

3.1.3. Association between the Feeling of Being Informed and Safe and Psychosomatic Symptoms for the Work with COVID-19 Patients Directly

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christopher, D.; Isaac, B.; Rupali, P.; Thangakunam, B. Health-care preparedness and health-care worker protection in COVID-19 pandemic. Lung India 2020, 37, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, D.; Singh, P.M.; Gouda, P.; Goudra, B. An Overview of Health Care Worker Reported Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021, 34, S244–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheraton, M.; Deo, N.; Dutt, T.; Surani, S.; Hall-Flavin, D.; Kashyap, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers globally: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussmayr, K. Grafiken, die die Verbreitung des Coronavirus in Österreich und der Welt erklären. Available online: https://www.diepresse.com/5785804/15-grafiken-die-die-verbreitung-des-coronavirus-in-oesterreich-und-der-welt-erklaeren (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Bria, M.; Baban, A.; Dumitrascu, D. Systematic Review of Burnout Risk Factors among European Healthcare Professionals. Cogn. Brain Behav. 2012, 16, 423–452. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso, Z.L.; Holcombe, K.J.; McCluney, C.L.; Fisher, G.G.; McGonagle, A.K.; Friebe, S.J. Burnout and Engagement. Work. Health Saf. 2016, 64, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, C.-H.; Tseng, P.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, K.-H.; Chen, Y.-Y. Burnout in the intensive care unit professionals. Medicine 2016, 95, e5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateen, F.J.; Dorji, C. Health-care worker burnout and the mental health imperative. Lancet 2009, 374, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyashanu, M.; Pfende, F.; Ekpenyong, M. Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J. Interprof. Care 2020, 34, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, M.; Goh, E.T.; Scott, A.; Martin, G.; Markar, S.; Flott, K.; Mason, S.; Przybylowicz, J.; Almonte, M.; Clarke, J.; et al. What Has Been the Impact of Covid-19 on Safety Culture? A Case Study from a Large Metropolitan Healthcare Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinley, N.; McCain, R.S.; Convie, L.; Clarke, M.; Dempster, M.; Campbell, W.J.; Kirk, S.J. Resilience, burnout and coping mechanisms in UK doctors: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e031765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekele, F.; Hajure, M. Magnitude and determinants of the psychological impact of COVID-19 among health care workers: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 205031212110125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Scherer, N.; Felix, L.; Kuper, H. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.; Kang, L.; Li, J.; Gu, J. A Key Factor for Psychosomatic Burden of Frontline Medical Staff: Occupational Pressure During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 590101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Azizi, M.; Moosazadeh, M.; Mehravaran, H.; Ghasemian, R.; Reskati, M.H.; Elyasi, F. Occupational burnout in Iranian health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Jin, Y.; He, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, X.; et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in healthcare workers deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 56, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Wang, E.; Jin, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yu, C.; Luo, C.; Zhang, L.; et al. COVID-19 Outbreak Can Change the Job Burnout in Health Care Professionals. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 563781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Worker Wellness: A Scoping Review. West J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M. Work-related stress and psychosomatic medicine. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2010, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakib, N.; Akter, T.; Zohra, F.; Bhuiyan, A.K.M.I.; Mamun, M.A.; Griffiths, M.D. Fear of COVID-19 and Depression: A Comparative Study among the General Population and Healthcare Professionals during COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis in Bangladesh. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieh, C.; Budimir, S.; Humer, E.; Probst, T. Comparing Mental Health during COVID-19 Lockdown and Six Months Later in Austria: A Longitudinal Study. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräfe, K.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W.; Löwe, B. Screening psychischer Störungen mit dem ‘Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ-D)’. Ergebnisse der deutschen Validierungsstudie. Diagnostica 2004, 50, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, J.; Shi, L.; Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Gong, Y.; Huang, W.; Yuan, K.; Yan, W.; et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study in China. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wańkowicz, P.; Szylińska, A.; Rotter, I. Assessment of Mental Health Factors among Health Professionals Depending on Their Contact with COVID-19 Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, A.M.; Knecht, M.; Wiese, B.S. Multidomain Engagement and Self-Reported Psychosomatic Symptoms in Middle-Aged Women and Men. Gerontology 2014, 60, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crocamo, C.; Bachi, B.; Calabrese, A.; Callovini, T.; Cavaleri, D.; Cioni, R.M.; Carrà, G. Some of us are most at risk: Systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates of depressive symptoms among healthcare workers during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 131, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehner, C. Why is depression more common among women than among men? Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 4, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, M.E.M.; Travis, D.J.; Pyun, H.; Xie, B. The Impact of Supervision on Worker Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2009, 83, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocchiara, R.A.; Peruzzo, M.; Mannocci, A.; Ottolenghi, L.; Villari, P.; Polimeni, A.; Guerra, F.; La Torre, G. The Use of Yoga to Manage Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strauss, C.; Gu, J.; Montero-Marin, J.; Whittington, A.; Chapman, C.; Kuyken, W. Reducing stress and promoting well-being in healthcare workers using mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for life. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021, 21, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, P.; Ross, J.; Moriarty, J.; Mallett, J.; Schroder, H.; Ravalier, J.; Manthorpe, J.; Currie, D.; Harron, J.; Gillen, P. The Role of Coping in the Wellbeing and Work-Related Quality of Life of UK Health and Social Care Workers during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windarwati, H.D.; Ati, N.A.L.; Paraswati, M.D.; Ilmy, S.K.; Supianto, A.A.; Rizzal, A.F.; Sulaksono, A.D.; Lestari, R.; Supriati, L. Stressor, coping mechanism, and motivation among health care workers in dealing with stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 56, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechter, A.; Diaz, F.; Moise, N.; Anstey, D.E.; Ye, S.; Agarwal, S.; Birk, J.L.; Brodie, D.; Cannone, D.E.; Chang, B.; et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Al Sinani, M.; Al-Lenjawi, B. Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 141, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, V.H. Confronting Health Worker Burnout and Well-Being. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Topic | Questions | Answer Options |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 work-related fears | During the COVID-19 pandemic, I am anxious about… …my job. …the health of my relatives. …my own health. …the commercial crisis. …nothing. | Yes/No |

| Feeling save and informed (only for frontline workers in the health sector | I feel sufficiently informed for my work with COVID-19 patients and my own safety by my employer. I feel sufficiently informed for my work with COVID-19 patients and my own safety by the government. During the work with COVID-19 patients, I feel safe. | I agree/I disagree |

| Healthcare Profession | t1 | t2 | t3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Doctors | 70 | 150 | 160 |

| Medical Doctors in Training | 28 | 45 | 60 |

| Psychologists and Therapists | 6 | 185 | 86 |

| Medical Technical Assistants | 2 | 123 | 165 |

| Scientific Staff | 74 | 33 | 45 |

| Nurses or Nursing Assistants | 0 | 777 | 290 |

| Facility Management | 0 | 5 | 4 |

| Administrative Staff | 0 | 174 | 181 |

| Age in Years | t1 | t2 | t3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–30 | 12.5 | 20.4 | 491 |

| 31–40 | 27.6 | 19.8 | 421 |

| 41–50 | 15.9 | 19.8 | 414 |

| 51–60 | 18.5 | 16.5 | 350 |

| 61–70 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 35 |

| 71–80 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1 |

| t1 | |||||

| PHQ-D psychosomatic symptoms | PHQ-D depression | PHQ-D anxiety | COVID-19 work-related fears | ||

| PHQ-D psychosomatic symptoms | r | 1 | 0.577 ** | 0.056 | 0.392 ** |

| p | 0.000 | 0.808 | 0.000 | ||

| t2 | |||||

| PHQ-D psychosomatic symptoms | PHQ-D depression | PHQ-D anxiety | COVID-19 work- related fears | ||

| PHQ-D psychosomatic symptoms | r | 1 | 0.589 ** | −0.107 | 0.004 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.221 | 0.968 | ||

| t3 | |||||

| PHQ-D psychosomatic symptoms | PHQ-D depression | PHQ-D anxiety | COVID-19 work- related fears | ||

| PHQ-D psychosomatic symptoms | r | 1 | 0.582 ** | −0.187 * | 0.178 ** |

| p | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.000 | ||

| Feeling Informed and Safe | PHQ-D Psychosomatic Symptoms | COVID-19 Work-Related Fears | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t1 | r | −0.371 ** | −0.171 |

| p | 0.007 | 0.226 | |

| t2 | r | −0.193 ** | −0.122 |

| p | 0.002 | 0.691 | |

| t3 | r | −0.191 ** | −0.088 * |

| p | 0.000 | 0.027 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lenger, M.; Maget, A.; Dalkner, N.; Lang, J.N.; Fellendorf, F.T.; Ratzenhofer, M.; Schönthaler, E.; Fleischmann, E.; Birner, A.; Bengesser, S.A.; et al. Feeling Informed and Safe Are Important Factors in the Psychosomatic Health of Frontline Workers in the Health Sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021533

Lenger M, Maget A, Dalkner N, Lang JN, Fellendorf FT, Ratzenhofer M, Schönthaler E, Fleischmann E, Birner A, Bengesser SA, et al. Feeling Informed and Safe Are Important Factors in the Psychosomatic Health of Frontline Workers in the Health Sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021533

Chicago/Turabian StyleLenger, Melanie, Alexander Maget, Nina Dalkner, Jorgos N. Lang, Frederike T. Fellendorf, Michaela Ratzenhofer, Elena Schönthaler, Eva Fleischmann, Armin Birner, Susanne A. Bengesser, and et al. 2023. "Feeling Informed and Safe Are Important Factors in the Psychosomatic Health of Frontline Workers in the Health Sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Austria" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021533