Diabetes Mellitus Family Assessment Instruments: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Assessment of Methodological Quality and Assessment of Measurement Properties

- -

- Correlations with instruments used to measure the same construct should be >0.50;

- -

- Correlations with instruments used to measure related constructs should be in the range of 0.30–0.50.

2.5. Evidence Synthesis

3. Results

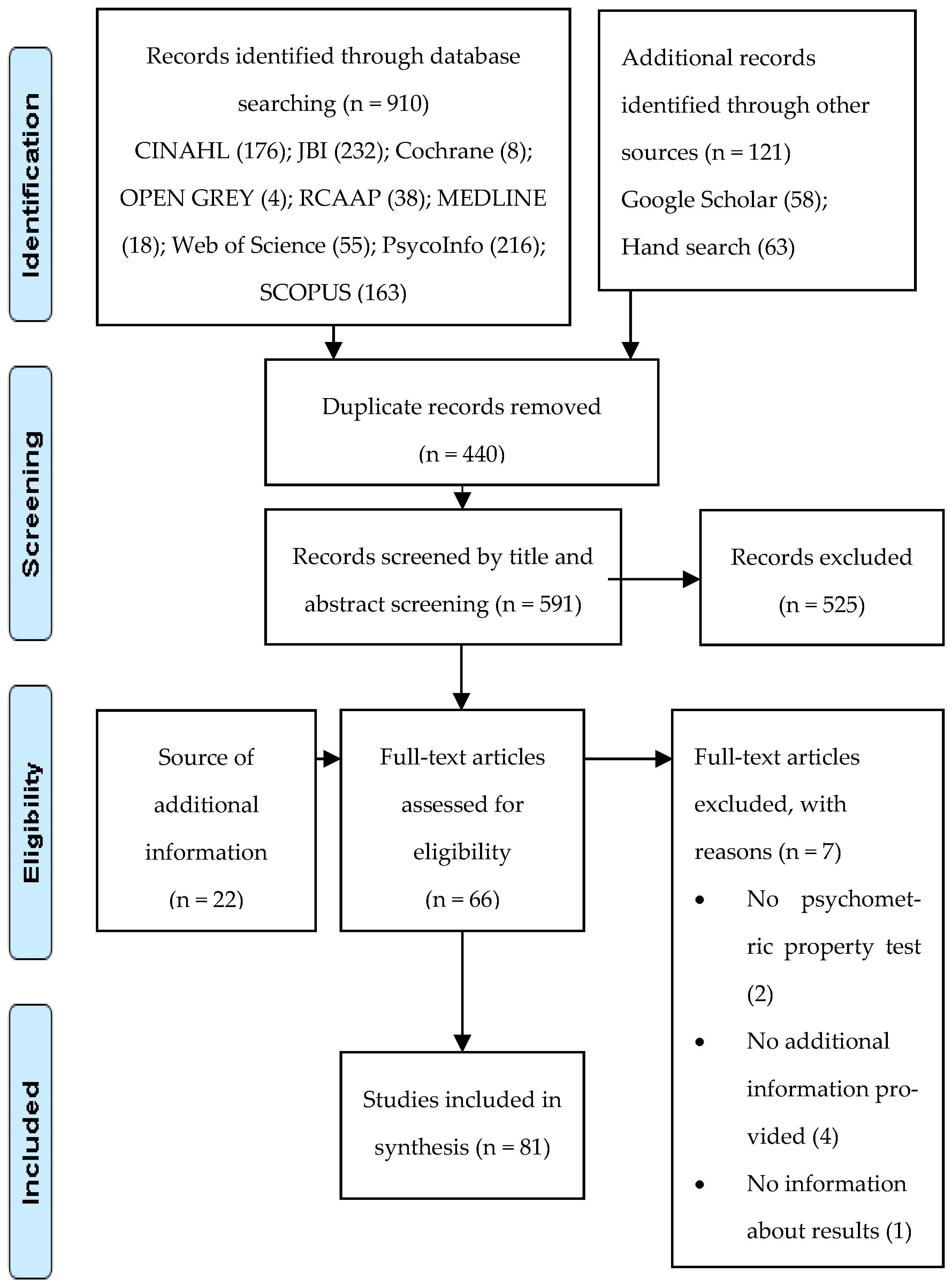

3.1. Studies Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Instruments Characteristics

3.4. Methodological Quality of Included Studies

3.5. Quality of Psychometric Properties of Instruments

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meleis, A.I. Theoretical Nursing: Development and Progress, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaakinen, J.; Coehlo, D.; Steele, R.; Robinson, M. Family Health Care Nursing: Theory, Practice and Research, 6th ed.; F. A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shajan, Z.; Snell, D. Wright & Leahey’s. Nurses and Families: A Guide to Family Assessment and Intervention; F. A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rosland, A.; Kieffer, E.; Spencer, M.; Sinco, B.; Palmisano, G.; Valerio, M.; Heisler, M. Do pre-existing diabetes social support or depressive symptoms influence the effectiveness of a diabetes management intervention? Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkisson, S.; Pillay, B.J.; Sibanda, W. Social support and coping in adults with type 2 diabetes. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2017, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Frías-Osuna, A.; Palomino-Moral, P.A.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J. Social support and subjective burden in caregivers of adults and older adults: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, H.A.; Van Der Horst, F.G.; Knoops, L.; Ryckman, R.M.; Crebolder, H.F.; Van Den Borne, B.H. Social support in diabetes: A systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 59, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravizade Tabasi, H.; Madarshahian, F.; Khoshniat Nikoo, M.; Hassanabadi, M.; Mahmoudirad, G. Impact of family support improvement behaviors on anti-diabetic medication adherence and cognition in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2014, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.A.; Piette, J.D.; Heisler, M.; Rosland, A.-M. Diabetes Distress and Glycemic Control: The Buffering Effect of Autonomy Support From Important Family Members and Friends. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 9th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L.M.; Leahey, M. Nurses and Families Nurses Families: A Guide to Family Assessment and Intervention, 6th ed.; F. A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beavers, W.R.; Hampson, R.B. The Beavers systems model of family functioning. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.M.B.; Rocha, R.M.; Ribeiro, I.J.S. Depressive Symptoms and Family Functionality in the Elderly with Diabetes Mellitus. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 41, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmoude, E.; Tafazoli, M.; Parnan, A. Assessment of Family Functioning and Its Relationship to Quality of Life in Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Women. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 5, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkas, R.A.; Chamroonsawasdi, K. Family Functional-based Coaching Program on Healthy Behavior for Glycemic Control among Indonesian Communities: A Quasi-experimental Study. Oman Med. J. 2020, 35, e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, K.W.R.; Toonsiri, C.; Junprasert, S. Self-Efficacy, Psychological Stress, Family Support, and Eating Behavior On Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Belitung Nurs. J. 2016, 2, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Deatrick, J.A.; Feetham, S.L.; Levin, A. A Review of Diabetes Mellitus–Specific Family Assessment Instruments. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2011, 35, 405–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, M.; Riitano, D.; Wilson, S.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Mabire, C.; Cooper, K.; Da Cruz, D.M.; Moreno-Casbas, M.T.; Lapkin, S. Chapter 12: Systematic reviews of measurement properties. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C.; Russell, D. The Provisions of Social Relationships and Adaption to Stress. Adv. Pers. Relatsh. 1983, 1, 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Procidano, M.; Heller, K. Measures of Perceived Social Support from Friends and From Family: Three Validation Studies American. J. Community Psychol. 1983, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.; Grossman, R.; Pinski, R.; Patterson, T.; Nader, P. The Development of Scales to Measure Social Support for Diet and Exercise Behaviors. Prev. Med. 1987, 16, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.; Franks, P.; Harp, J.; McDaniel, S.; Campbell, T. Development of the family emotional involvement and criticism scale (FEICS): Expressed emotion a self-report scale measure. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 1992, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, F.; Nouwen, A.; Gingras, J.; Gosselin, M.; Audet, J. The assessment of diabetes-related cognitive and social factors: The Multidimensional Diabetes Questionnaire. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 20, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimet, G.; Dahlem, N.; Zimet, S.; Farley, G. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N.B.; Baldwin, L.M.; Bishop, D.S. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 1984, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Barrera, M., Jr.; McKay, H.G.; Boles, S.M. Social Support, Self-Management, and Quality of Life among Participants in an Internet-Based Diabetes Support Program: A Multi-Dimensional Investigation. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1999, 2, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.; Toobert, M.A. Social Environment and Regimen Adherence Among. Diabetes Care 1988, 11, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, M.-J.D.; Smilkstein, G.; Good, B.J.; Shaffer, T.; Arons, T. The Family APGAR Index: A study of construct validity. J. Fam. Pract. 1979, 8, 577–582. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, L.C.; McCaul, K.D.; E Glasgow, R. Supportive and Nonsupportive Family Behaviors: Relationships to Adherence and Metabolic Control in Persons with Type I Diabetes. Diabetes Care 1986, 9, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilkstein, G.; Ashworth, C.; Montano, D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J. Fam. Pract. 1982, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, C.B.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Chiarotto, A.; Westerman, M.J.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Mokkink, L.B. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarton, L.J.; Bakas, T.; Miller, W.R.; McLennon, S.M.; Huber, L.L.; Hull, M.A. Development and Psychometric Testing of the Diabetes Caregiver Activity and Support Scale. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesla, C.A.; Kwan, C.; Chun, K.M.; Stryker, L. Gender Differences in Factors Related to Diabetes Management in Chinese American Immigrants. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2014, 36, 1074–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.T.; Davis, W.K.; Connell, C.M.; Hess, G.E.; Funnell, M.M.; Hiss, R.G. Development and Validation of the Diabetes Care Profile. Eval. Health Prof. 1996, 19, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawon, S.R.; Hossain, F.B.; Adhikary, G.; Das Gupta, R.; Hashan, M.R.; Rabbi, F.; Ahsan, G.U. Attitude towards diabetes and social and family support among type 2 diabetes patients attending a tertiary-care hospital in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuhaida, M.H.; Siti Suhaila, M.Y.; Azidah, K.A.; Norhayati, N.M.; Nani, D.; Juliawati, M. Depression, anxiety, stress and so-cio-demographic factors for poor glycaemic control in patients with type II diabetes. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2019, 14, 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, M.S.; Kieffer, E.C.; Sinco, B.; Piatt, G.; Palmisano, G.; Hawkins, J.; Lebron, A.; Espitia, N.; Tang, T.; Funnell, M.; et al. Outcomes at 18 Months From a Community Health Worker and Peer Leader Diabetes Self-Management Program for Latino Adults. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePalma, M.T.; Rollison, J.; Camporese, M. Psychosocial predictors of diabetes management. Am. J. Health Behav. 2011, 35, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePalma, M.T.; Trahan, L.H.; Eliza, J.M.; Wagner, A.E. The relationship between diabetes self-efficacy and diabetes self-care in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2015, 22, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, Y.; Iwashita, S.; Ishii, K.; Inada, C.; Okada, A.; Tajiri, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Kato, T.; Nishida, K.; Ogata, Y.; et al. The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist (DFBC) for assessing the relationship between Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and their families with respect to adherence to treatment regimen. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 99, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Iwashita, S.; Okada, A.; Tajiri, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Kato, T.; Nakao, M.; Tsuboi, K.; Breugelmans, R.; Ishihara, Y. Development of a novel, short, self-completed questionnaire on empowerment for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and an analysis of factors affecting patient empowerment. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2014, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, B.; Bru, E. The relationship between diabetes-related distress and clinical variables and perceived support among adults with type 2 diabetes: A prospective study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, B.; Oftedal, B.; Bru, E. The relationship between clinical indicators, coping styles, perceived support and diabetes-related distress among adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberry, L.S.; Egede, L.E.; Wagner, J.A.; Osborn, C.Y. Stress, depression and medication nonadherence in diabetes: Test of the exacerbating and buffering effects of family support. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 38, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayberry, L.S.; Osborn, C.Y. Family involvement is helpful and harmful to patients’ self-care and glycemic control. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 97, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberry, L.S.; Rothman, R.L.; Osborn, C.Y. Family Members’ Obstructive Behaviors Appear to Be More Harmful among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes and Limited Health Literacy. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, K.J.; Osborn, C.Y.; Mayberry, L.S. Patient-perceived family stigma of type 2 diabetes and its consequences. Fam. Syst. Health 2018, 36, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddison, C. Family support and conflict among adults with type 2 diabetes. Eur. Diabetes Nurs. 2010, 7, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofulu, F.; Unsalavdal, E.; Arkan, B. Validity and reliability of the diabetes family support and conflict scale in Turkish. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2017, 33, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Urzúa, A.; Cabrera, C.; González, C.; Arenas, P.; Guzmán, M.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Irarrázaval, M. Psychometric properties of the diabetes mellitus 2 treatment adherence scale version III (EATDM-III) adapted for Chilean patients. Rev. Med. Chil. 2015, 143, 733–743. [Google Scholar]

- Wichit, N.; Mnatzaganian, G.; Courtney, M.; Schulz, P.; Johnson, M. Psychometric testing of the Family-Career Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 26, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayberry, L.S.; Berg, C.A.; Greevy, R.A.; Wallston, K.A. Assessing helpful and harmful family and friend involvement in adults’ type 2 diabetes self-management. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberry, L.S.; Greevy, R.A.; Huang, L.-C.; Zhao, S.; Berg, C.A. Development of a Typology of Diabetes-Specific Family Functioning among Adults with Type 2. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, K.; Cummings, D.M.; Lutes, L.; Solar, C. Psychometric Properties of the Family Support Scale Adapted for African American Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ethn. Dis. 2015, 25, 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, R.; Trief, P.M.; Scales, K.; Weinstock, R.S. “Miscarried helping” in adults with Type 2 diabetes: Helping for Health Inventory-Couples. Fam. Syst. Health 2017, 35, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.G.; Pedras, S.; Machado, J.C. Family variables as moderators between beliefs towards medicines and adherence to self-care behaviors and medication in type 2 diabetes. Fam. Syst. Health 2014, 32, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderimagham, S.; Niknami, S.; Abolhassani, F.; Hajizadeh, E.; Montazeri, A. Development and psychometric properties of a new social support scale for self-care in middle-aged patients with type II diabetes (S4-MAD). BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Epel, O.; Heymann, A.D.; Friedman, N.; Kaplan, G. Development of an unsupportive social interaction scale for patients with diabetes. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2015, 9, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennich, B.B.; Munch, L.; Egerod, I.; Konradsen, H.; Ladelund, S.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsbøll, T.; Røder, M.; Overgaard, D. Patient Assessment of Family Function, Glycemic Control and Quality of Life in Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Incipient Complications. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 43, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamali, M.; Konradsen, H.; Lauridsen, J.T.; Østergaard, B. Translation and validation of the Danish version of the brief family assessment measure III in a sample of acutely admitted elderly medical patients. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 32, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Hu, J. Effectiveness of a Family-based Diabetes Self-management Educational Intervention for Chinese Adults with Type 2 Diabetes in Wuhan, China. Diabetes Educ. 2016, 42, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Toobert, D.J.; Barrera, M.; Strycker, L.A. The Chronic Illness Resources Survey: Cross-validation and sensitivity to intervention. Health Educ. Res. 2004, 20, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basinger, E.D. Testing a Dimensional Versus a Typological Approach to the Communal Coping Model in the Context of Type 2 Diabetes. Health Commun. 2019, 35, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D. FACES IV and the Circumplex Model: Validation Study. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2011, 37, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, H.; Sato, J.; Suzuki, T.; Ban, N. Family issues and family functioning of Japanese outpatients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2013, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, K.E.; Fain, J.A. Factors Affecting Resilience in Families of Adults with Diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2016, 42, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odume, B.B.; Ofoegbu, O.S.; Aniwada, E.C.; Okechukwu, E.F. The influence of family characteristics on glycaemic control among adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus attending the general outpatient clinic, National Hospital, Abuja, Nigeria. South Afr. Fam. Pract. 2015, 57, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosland, A.M.; Heisler, M.; Choi, H.J.; Silveira, M.J.; Piette, J.D. Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: Do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illn. 2010, 6, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toro, M.D.C.C.; Garcés, C.R.R. Funcionalidad Familiar en Pacientes Diabeticos e Hipertensos Compensados y Descompensados. Family Functionality in Diabetic and Hipertensive Patients Compensated and Descompensated. Theoria 2010, 19, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bahremand, M.; Rai, A.; Alikhani, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Shahebrahimi, K.; Janjani, P. Relationship Between Family Functioning and Mental Health Considering the Mediating Role of Resiliency in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 7, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J. Family functioning in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients with and without depressive symp-toms: A cross-sectional study. Psychopathology 2014, 47, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iloh, G.U.P.; Collins, P.I.; Amadi, A.N. Family functionality, medication adherence, and blood glucose control among ambulatory type 2 diabetic patients in a primary care clinic in Nigeria. Int. J. Health Allied Sci. 2018, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.M.; Trevino, D.B.; Islam, J.; Denner, L. The biopsychosocial milieu of type 2 diabetes: An exploratory study of the impact of social relationships on a chronic inflammatory disease. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2010, 40, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncone, R.; Mazza, M.; Ussorio, D.; Pollice, R.; Falloon, I.R.; Morosini, P.; Casacchia, M. The Questionnaire of Family Functioning: A Preliminary Validation of a Standardized Instrument to Evaluate Psychoeducational Family Treatments. Community Ment. Health J. 2007, 43, 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Huidobro, D.; Bittner, M.; Brahm, P.; Puschel, K. Family intervention to control type 2 diabetes: A controlled clinical trial. Fam. Pract. 2010, 28, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrain, M.E.; Zegers, B.; Diez, I.; Trapp, A. Validez y Confiabilidad de la Versión Española de la Escala del Estilo de Funcio-namento Familiar (EFF) de Dunst, Trivette & Deal para el Diagnostico del Funcionamento Familiar en la Población Chilena. Psykhe 2003, 12, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L.; Santos, C.; Bastos, C.; Guerra, M.; Martins, M.M.; Costa, P. Adaptation and validation of the Instrumental Expressive Social Support Scale in Portuguese older individuals. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2018, 26, e3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regufe, V.G. Autogestão no Doente Diabético: Papel do Enfermeiro na Promoção da Autonomia; Escola Superior de Enfermagem do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G.C.; Lynch, M.F.; McGregor, H.A.; Ryan, R.M.; Sharp, D.; Deci, E.L. Validation of the “Important Other” Climate Questionnaire: Assessing Autonomy Support for Health-Related Change. Fam. Syst. Health 2006, 24, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.; Kim, M. Self-Care Behaviors of Nepalese Adults with Type 2 Diabetes A Mixed Methods Analysis. Nurs. Res. 2016, 65, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Nguyen, T.; Park, H. Validation of multidimensional scale of perceived social support in middle-aged Korean women with diabetes. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work. Dev. 2012, 22, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senol-Durak, E. Stress Related Growth among Diabetic Outpatients: Role of Social Support, Self-Esteem, and Cognitive Processing. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 118, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerusalem, M.; Zyga, S.; Theofilou, P. Association of Type 1 Diabetes, Social Support, Illness and Treatment Perception with Health Related Quality of Life. GeNeDis 2016 2017, 988, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, K.; Freund, T.; Gensichen, J.; Miksch, A.; Szecsenyi, J.; Steinhaeuser, J. Adaptation and psychometric properties of the PACIC short form. Am. J. Manag. Care 2012, 18, e55-60. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolucci, A.; Burns, K.K.; Holt, R.I.G.; Lucisano, G.; Skovlund, S.E.; Kokoszka, A.; Benedetti, M.M.; Peyrot, M. Correlates of psychological outcomes in people with diabetes: Results from the second Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN2™) study. Diabet. Med. 2016, 33, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, M.; Burns, K.K.; Hollahan, D.; Ross, S.; Hahn, J. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs Second Study (DAWN2): Understanding Diabetes-Related Psychosocial Outcomes for Canadians with Diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2016, 40, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, M.; Willaing, I.; Holt, R.I.G. Emerging adulthood and Type 1 diabetes: Insights from the DAWN2 Study. Diabet. Med. 2018, 35, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, M.M.; Pasvogel, A.; Murdaugh, C. Effects of a Family-Based Diabetes Intervention on Family Social Capital Outcomes for Mexican American Adults. Diabetes Educ. 2019, 45, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.A.; Schindler, I.; Smith, T.; Skinner, M.; Beveridge, R. Perceptions of the Cognitive Compensation and Interpersonal En-joyment Functions of Collaboration among Middle-Aged and Older Married Couples. Psychol. Aging 2011, 26, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghafri, T.S.; Al-Harthi, S.; Al-Farsi, Y.; Craigie, A.M.; Bannerman, E.; Anderson, A.S. Changes in self-efficacy and social support after an intervention to increase physical activity among adults with type 2 diabetes in oman a 12-month follow-up of the movediabetes trial. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2021, 21, e42–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, V.J.; Petosa, R. Social cognitive theory correlates of moderate-intensity exercise among adults with type 2 diabetes. Psychol. Health Med. 2015, 21, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, A.; Ghofranipour, F.; Heydarnia, A.R.; Nabipour, I.; Shokravi, F.A. Validity and Reliability of the Social Support Scale for Exercise Behavior in Diabetic Women. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2010, 23, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, K.M.; Kwan, C.M.L.; Strycker, L.A.; Chesla, C.A. Acculturation and bicultural efficacy effects on Chinese American immi-grants’ diabetes and health management. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 39, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, P.; Severinsen, C.; Good, G.; O’Donoghue, K. Social environment and quality of life among older people with diabetes and multiple chronic illnesses in New Zealand: Intermediary effects of psychosocial support and constraints. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 44, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osmancevic, S.; Schoberer, D.; Lohrmann, C.; Großschädl, F. Psychometric properties of instruments used to measure the cultural competence of nurses: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 113, 103789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Instrument | References | Type of Measure | Target Population (According to the Validation Study) | Construct(s) | Subscales, Number of Items | Response Options | Theoretical Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus-Specific Instruments | |||||||

| Diabetes Caregiver Activity and Support Scale (D-CASS) | [37] | Patient interview | Family. Target family caregivers of persons with T2DM | Caregiver perceptions of difficulty with activities and supportive behaviors specifically while providing care for a person with T2DM | 11 items Unidimensional scale | 7-point Likert scale | Literature Review |

| Diabetes Care Profile (DCP) | [7,38,39,40,41,42] | Self-reported | Patients/Target patients with diabetes | Social and psychological factors related to diabetes and its treatment | 234 items with 16 scales (control problems, social and personal factors, positive attitude, negative attitude, self-care ability, importance of care, self-care adherence, diet adherence, medical barriers, exercise barriers, monitoring barriers, understanding management practice, long-term care benefits, support needs, support, and support attitude) | Filling in the blanks with the correct answers or by choosing the single best answer | Diabetes Educational Profile and Health Belief Model |

| Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist (DFBC) | [31,43,44,45,46,47,48] | Self-reported | Patient/family member dyad. Target insulin-dependent Diabetes Mellitus (IDDM) patients and families | Supportive and non-supportive family behaviors specific to the diabetes self-care regimen (drug therapy, blood glucose measurement, exercise, and diet) | 16 items that can be divided into 2 subscales for analysis (positive feedback—9 questions; negative feedback—7 questions) | 5-point Likert scale | Literature review including information from people diagnosed with diabetes and a health professional who is familiar with the disease |

| Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist-II (DFBC-II) | [29,49,50,51,52] | Self-reported | Patients/family member dyad. Target patients with type 2 diabetes | Family member’s actions toward the person with type II diabetes (medication taking, glucose testing, exercise, and diet) | DFBC-II version for a partner or significant other: 17 items that can be divided into 2 subscales for analysis (positive feedback—9 questions; negative feedback—7 questions) open-ended item DFBC-II version for diagnosed person: 17 items and a new section designed to assess 17 family behaviors | 5-point Likert scale 7-point Likert scale (DFBC-II section for diagnosed person) | Literature Review and Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist (DFBC) |

| Diabetes Family Support and Conflict scale (DFSC) | [53,54] | Self-reported | Patients. Target patients with type 2 DM | Diabetes-related family support and conflict | 10 items including 2 subscales (supportive—6 items; unsupportive—4 items) | 4-point Likert scale | Literature review and information from healthcare professionals and patients with diabetes |

| Diabetes Mellitus 2 treatment adherence scale version III (EATDM-III) | [55] | Self-reported | Patients. Target patients with type 2 diabetes | Treatment adherence | 30 items including 6 subscales (physical exercise, family support, medical control and treatment, community support and organization, diet, and information) | 5-point Likert scale | Literature Review and subjective reports from providers and patients |

| Diabetes Support Scale (DSS) | [28,42] | Self-reported | Patients. Target patients with diabetes (type 1 and 2) | Diabetes social support | 12 items including 3 subscales (emotional support, advice, information) | 7-point Likert scale | Literature Review and rational-theoretical approach |

| Empowerment questionnaire | [46] | Self-reported | Patients. Target patients with type 2 diabetes | Empowerment of type 2 diabetes patients (based on self-managed dietary/exercise behaviors, psychological impact, and family support) | 31 items including 5 scales (self-managed dietary behaviors, self-managed exercise behaviors, psychological impact of diabetes, and positive and negative feedback in patient-family communication) and 13 questions on background | 5-point Likert scale Filling in the blanks with the correct answers | Literature review and Japanese-language versions of the Appraisal of Diabetes Scale and Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist |

| Family-Carer Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale (F-DMSES) | [56] | Self-reported | Families. Target family of patients with type 2 diabetes | Family-caretaker diabetes management and self-efficacy. | 14 items including 4 subscales (General diet and blood glucose monitoring, medication and complication, diet in different situations, weight control, and physical activities) | 5-point Likert scale | Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale (DMSES) |

| Family and Friend Involvement in Adults’ Diabetes (FIAD) | [57,58] | Self-reported | Patients. Target patients with type 2 diabetes | Family/friend involvement | 16 items including 2 subscales (helpful involvement, harmful involvement) | 5-point Likert scale | Literature review, cognitive interviews, and expert input |

| Family Support Scale adapted for African American women with type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (FSS-AA) | [59] | Self-reported | Patients. Target women with uncontrolled T2DM | Diabetes-specific social support | 16 items including 3 subscales (parent and spouse/partner support, community and medical support, extended family and friends support) | 5-point Likert scale | Original Dunst Family Support Scale (FSS) |

| Helping for Health Inventory: Couples Version (HHI-C) | [60] | Patient interview | Patients. Target patients with type 2 diabetes | “Miscarried helping” in couples | 15 items including 3 subscales (Conflict/Blame, Partner Investment, Resistance) | 5-point Likert scale | Theoretical concept of “miscarried helping” and “Helping for Health Inventory” scale |

| Multidimensional Diabetes Questionnaire (MDQ) | [25,61] | Self-reported | Patients. Target patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes | Patients’ psychosocial adjustment to diabetes | 41 items grouped into three sections: Section I: 16 items including 3 scales (perceived interference caused by diabetes to daily activities, work, and social and recreational activities; perceived severity of diabetes; perceived diabetes-related social support from a significant other, family, friends, and health professionals) Section II 12 items including 2 scales (positive reinforcing behaviors and specific form of non-supportive behaviors) Section III 13 items including 2 scales (self-efficacy expectancies and outcome expectancies) | Section I and II: 7-point Likert scale Section III: rated from 0 to 100 | Literature Review and Social Learning Theory |

| Social Support Scale for Self-care in Middle-aged Patients (S4-MAD) | [62] | Patient interview | Patients. Target patients with diabetes | Social support for self-care in diabetic patients | 30 items including 5 subscales (nutrition, physical activity, self-monitoring of blood glucose, foot care, and smoking) | 5-point Likert scale | Literature review |

| Unsupportive social interaction scale (USIS) | [63] | Patient interview | Patients. Target patients with diabetes | Unsupportive social interactions | 15 items including 2 scales (interference and insensitivity) | 5-point Likert scale | Literature review and information from patients with diabetes |

| Generic instruments | |||||||

| Brief Family Assessment Measure-Brief (Brief FAM-III) | [64,65] | Self-reported | Patients. Target patients with type 2 diabetes | Family’s strengths and weaknesses | 42 items including 3 scales (general, dyadic relationships, and self-rating) | 4-point Likert scale | Model of Family Functioning |

| Chronic Illness Resources Survey (CIRS) | [66,67] | Self-reported | Patients. Target post-menopausal women with type 2 diabetes | Multilevel support resources from proximal support (e.g., family and friends) to more distal factors (e.g., neighborhood or community) | 22 items including 9 subscales (personal; family and friends; physician/health care team; neighborhood/community; organizations; work; media and policy; dietary and physical activity) | 6-point Likert scale | Multilevel, Social–Ecological Model |

| Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (FACES IV) | [68,69,70] | Self-reported | Adults. Target Students and nonclinical family | Family functioning (family adaptability and cohesion) | 42 items including 2 Balanced scales (cohesion and flexibility) and 4 Unbalanced scales (disengaged, enmeshed chaos, and rigid) | 5-point Likert scale | Circumplex model and family therapists fromAmerican Association for Marriage and Family Therapy |

| Family APGAR Index | [15,30,32,71,72,73,74] | Self-reported | Clinical group(patients)/nonclinical group dyad. Target “normal” families’ members and psychiatric outpatients | Global family function | 5-item questionnaire that is designed to test five areas of family function (adaptation; partnership; growth, affection, and resolve) Unidimensional scale | 3-point Likert scale | Literature review |

| Family Assessment Device (FAD) | [16,27,75,76,77] | Self-reported | Students and patient’s family. Target psychology students and a group of patient’s family | Family functioning | 53 items (currently is in use a 60-items version) including 7 scales (general functioning, communication, affective involvement, roles, problem solving, affective responsiveness, behavior control) | 4-point Likert scale | McMaster Model of Family Functioning (MMFF) |

| Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS) | [24,58,78] | Self-reported | Patients. Target patients receiving primary medical care | Perceived family criticism and emotional involvement | 2 subscales (Family’s Perceived Criticism—7 items; Intensity of Emotional Involvement—7 items) | 5-point Likert scale | Expressed Emotion (EE) theory |

| Family Function Questionnaire (FFQ) | [17,79] | Self-reported | Families. Target caregivers of psychiatric patients | Perceived family function | 24 items including 3 subscales (problem-solving, communication, and personal goal) | 4-point Likert scale | Literature Review and Cognitive-behavioral Family Treatment |

| Family Functioning Style Scale | [80,81] | Patient interview | Mother/father dyad. Target families | Family functioning style | 22 item questionnaire scale (the original scale developed by Deal, Trivette and Dunst, 1988, use a 26-item version) including 3 subscales (interactional patterns and family values, family commitment, intrafamily coping strategies) | 5-point Likert scale | Family Functioning Style Model |

| Instrumental Expressive Social Support Scale (IESS) | [82,83] | Self-reported | Older people. Target community-dwelling older | Social Support | 16 items (the original scale used a 20 items version) including 3 subscales (familiar and socio-affective support, sense of control, and financial support) | 5-point Likert scale | Literature Review |

| Important Other Climate Questionnaire (IOCQ) | [58,84] | Self-reported | Patients. Target smokers | Perceived autonomy supportiveness of an “important other” | 6 items Unidimensional | 7-point Likert scale | Care Climate Questionnaire (HCCQ) |

| Multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) | [26,72,85,86,87,88] | Self-reported | Patients. Target women with diabetes and critical social support | Perceived social support | 12 items including 3 subscales (family, friends, and significant others) | 7-point Likert-type scale | Literature Review |

| Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care-Short Form (PACIC-SF) | [89,90,91,92] | Self-reported | Patients. Target primary care patients | Perceived self-management support | 11 items Unidimensional scale | 5-point Likert-type scale | Chronic Care Model (CCM) |

| Perceived social support from friends (PSS-Fr) and from family (PSS-Fa) Scales | [22,93] | Self-reported | Students. Target undergraduates | Perceived social support | 20 items PSS-Fr Unidimensional scale 20 items PSS-Fa Unidimensional scale | Multichotomous response | Literature Review |

| Perceptions of Collaboration Questionnaire (PCQ) | [58,94] | Self-reported | Wife and husband dyad. Target married couples | Perceptions of collaboration (solving everyday problems and making decisions) | 9 items including 3 subscales (cognitive compensation, interpersonal enjoyment, and frequency of collaboration) | 5-point Likert scale | Literature Review |

| Scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors | [23,93,95,96,97] | Self-reported | Students and staff. Target psychology students and staff members of a health-promotion research study | Perceived social support specific to health-related eating and exercise behaviors | 10-item Social Support for Eating Habits (SSEH) scale: 2 subscales (encouragement; discouragement); 13-item Social Support for Physical Activity (SSPA) scale: 2 subscales (participation, rewards, and punishments) | 5-point Likert scale | Literature review and structured in-depth interviews with people who were in the process of changing their diet and/or exercise habits report |

| Social Provision Scale (SPS) | [21,98,99] | Self-reported | College students and public-school teachers. Target different types of population | Social support | 24 items including 6 subscales (attachment, reassurance of worth, reliable alliance, social integration, guidance, and opportunity for nurturance) | 4-point Likert scale | Model of the Social Provisions |

| Instrument | References | Instrument Development | Content Validity | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Cognitive Interview | Total Instrument Development | ||||

| Brief Family Assessment Measure (Brief FAM-III) | [65] | A | A | A | A | |

| [64] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity not reported | |

| Chronic Illness Resources Survey (CIRS) | [67] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity not reported |

| [66] | ||||||

| Diabetes Caregiver Activity and Support Scale (D-CASS) | [37] | A | - | D | D | Important methodological flaws pilot test and content validity |

| Diabetes Care Profile (DCP) | [39] | A | - | D | - | Important methodological flaws in the, pilot test and content validity. This instrument evolved from the instrument Diabetes Educational Profile (DEP) |

| [38] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| [7] | ||||||

| [40] | ||||||

| [41] | ||||||

| [42] | ||||||

| Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist (DFBC) | [31] | A | A | A | D | Content validity: important methodological flaws in relevance and comprehensibility (professionals) |

| [43] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| [48] | ||||||

| [45] | ||||||

| [46] | ||||||

| [47] | ||||||

| [44] | ||||||

| Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist-II (DFBC-II) | [29] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported |

| [51] | ||||||

| [49] | ||||||

| [50] | ||||||

| [52] | ||||||

| Diabetes Family Support and Conflict scale (DFSC) | [53] | A | A | A | A | |

| [54] | - | - | - | A | Information about instrument development were not reported | |

| Diabetes Mellitus 2 treatment adherence scale version III (EATDM-III) | [55] | - | - | - | D | Information about instrument development were not reported. Not clear if professionals were asked about the relevance of the instrument’s items |

| Diabetes Support Scale (DSS) | [28] [42] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported |

| Empowerment questionnaire | [46] | - | - | - | - | This instrument comprised questions from other validated instruments. Information about instrument design, pilot test, and content validity were not reported |

| Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (FACES IV) | [69] | - | - | - | - | This instrument was the latest version of the original FACES Information about instrument design, pilot test, and content validity were not reported |

| [70] | ||||||

| [68] | ||||||

| Family APGAR Index | [30] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported |

| [32] | ||||||

| [73] | ||||||

| [74] | ||||||

| [72] | ||||||

| [71] | ||||||

| [15] | ||||||

| Family Assessment Device (FAD) | [27] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported |

| [75] | ||||||

| [76] | ||||||

| [16] | ||||||

| [77] | ||||||

| Family-Carer Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale (F-DMSES) | [56] | A | A | A | D | Content validity: small number of professionals involved in relevance evaluation |

| Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS) | [24] | A | D | D | D | Important methodological flaws in the design, pilot test, and content validity |

| [78] | - | - | . | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| [58] | ||||||

| Family and Friend Involvement in Adults’ Diabetes (FIAD) | [93] | A | A | A | A | |

| [58] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| Family Function Questionnaire (FFQ) | [79] | A | A | A | D | Content validity: not clear about number of, or if, professionals were asked about relevance and comprehensiveness |

| [17] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| Family Functioning Style Scale | [81] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported |

| [80] | ||||||

| Family Support Scale adapted for African American women with type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (FSS-AA) | [59] | A | A | A | D | Content validity: the number of professionals involved in data analysis was not clear |

| Helping for Health Inventory: Couples Version (HHI-C) | [60] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported |

| Instrumental Expressive Social Support Scale (IESS) | [83] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported |

| [82] | ||||||

| Important Other Climate Questionnaire (IOCQ) | [84] | A | D | D | D | Important methodological flaws in the design, pilot test, and content validity. |

| [58] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| Multidimensional Diabetes Questionnaire (MDQ) | [25] | A | D | D | D | Cognitive interview: it was not clear if the patients were asked about comprehensibility and comprehensiveness; Content validity: it was not clear how many professionals were involved and if they were asked about the relevance and comprehensiveness of the items |

| [61] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| Multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) | [26] | A | D | D | D | Cognitive interview: it was not clear if the patients were asked about comprehensibility and comprehensiveness; Content validity: it was not clear how many professionals were involved in data analysis and if they were asked about the relevance and comprehensiveness of the items |

| [86] | A | D | D | D | ||

| [87] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| [72] | ||||||

| [85] | ||||||

| [88] | ||||||

| Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care-Short Form (PACIC-SF) | [89] | A | - | D | - | No information about cognitive interview and about content validity |

| [90] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| [91] | ||||||

| [92] | ||||||

| Perceived social support from friends (PSS-Fr) and from family (PSS-Fa) Scales | [22] | A | - | D | - | No information about cognitive interview or about content validity |

| [93] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| Perceptions of Collaboration Questionnaire (PCQ) | [94] | A | - | D | - | No information about cognitive interview or about content validity |

| [58] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| Scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors | [23] | A | D | D | D | Cognitive interview: it was not clear if the patients were asked about comprehensibility and comprehensiveness of the instrument; Content validity: it was not clear how many professionals were involved in data analysis and if they were asked about the relevance and comprehensiveness of the items |

| [97] | A | A | A | A | ||

| [96] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| [93] | ||||||

| [95] | ||||||

| Social Provision Scale (SPS) | [21] | A | D | D | D | Cognitive interview: it was not clear if patients were asked about the comprehensibility and comprehensiveness of the instrument; Content validity: it was not clear how many professionals were involved in data analysis and if they were asked about the relevance and comprehensiveness of the items |

| [98] | - | - | - | - | Information about instrument development and content validity were not reported | |

| [99] | ||||||

| Social support scale for self-care in middle-aged patients (S4-MAD) | [62] | A | A | A | A | |

| Unsupportive social interaction scale (USIS) | [63] | A | A | A | D | Content validity: it was not clear if the patients were asked about the relevance and comprehensiveness of the items |

| Methodological Result | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | |||||||||

| Instrument | References | Box 3 | Box 4 | Box 5 | Box 6 | Box 7 | Box 8 | Box 9 | Box 10 |

| Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Cross-Cultural Validity/Measurement Invariance | Reliability | Measurement Error | Criterion Validity | Hypothesis Testing for Construct Validity | Responsiveness | ||

| Brief FAM-III | [65] | I | V | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [64] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| CIRS | [67] | - | V | - | V | - | - | A | |

| [66] | - | I | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| D-CASS | [37] | A | V | - | V | - | - | - | |

| DCP | [39] | V | V | - | - | - | V | A | |

| [38] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [7] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [40] | |||||||||

| [41] | |||||||||

| [42] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| DFBC | [31] | - | V | - | V | - | - | A | |

| [43] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [48] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [45] | A | V | - | I | - | A | |||

| [46] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [47] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [44] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| DFBC-II | [29] | - | V | - | V | - | - | A | - |

| [51] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [49] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [50] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [52] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| DFSC | [53] | A | V | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [54] | A | V | - | D | - | - | - | - | |

| EATDM-III | [55] | A | V | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| DSS | [28] | - | V | - | - | - | V | A | |

| [42] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Empowerment questionnaire | [46] | A | V | - | I | - | - | D | - |

| FACES IV | [69] | V | V | - | - | - | V | - | - |

| [70] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [68] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Family APGAR Index | [30] | - | V | - | - | - | - | A | - |

| [32] | - | V | - | V | - | - | A | - | |

| [73] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [74] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [72] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [71] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [15] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| FAD | [27] | - | V | - | - | - | V | A | - |

| [75] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [76] | - | V | - | D | - | - | - | - | |

| [16] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [77] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| F-DMSES | [56] | A | V | - | V | - | - | - | D |

| FEICS | [24] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [78] | V | V | - | - | - | V | A | - | |

| [58] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| FIAD | [93] | V | V | - | V | - | V | A | - |

| [58] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| FFQ | [79] | - | V | - | I | - | - | - | - |

| [17] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Family Functioning Style Scale | [81] | A | V | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [80] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| FSS-AA | [59] | A | V | - | V | - | V | - | - |

| HHI-C | [60] | - | V | - | V | - | V | - | - |

| IESS | [83] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [82] | V | V | - | - | - | - | A | - | |

| IOCQ | [84] | V | V | - | V | - | - | A | - |

| [58] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| MDQ | [25] | V | V | - | D | - | - | A | - |

| [61] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| MSPSS | [26] | V | V | - | V | - | - | - | - |

| [86] | A | V | - | - | - | V | A | - | |

| [87] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [72] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [85] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [88] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| PACIC-SF | [89] | A | V | - | - | - | - | A | - |

| [90] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [91] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [92] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| PSS-Fr and PSS-Fa | [22] | A | V | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [93] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| PCQ | [94] | V | V | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| [58] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors | [23] | A | V | - | D | - | V | A | - |

| [97] | V | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [96] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [93] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [95] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| SPS | [21] | V | V | - | - | - | - | A | - |

| [98] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| [99] | - | V | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| S4-MAD | [62] | V | V | - | V | - | - | - | - |

| USIS | [63] | A | V | - | A | - | - | A | - |

| Instrument | References | Rating Scores of Measurement Properties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Cross-Cultural Validity/Measurement Invariance | Reliability | Measurement Error | Criterion Validity | Hypothesis Testing for Construct Validity | Responsiveness | ||

| Brief FAM-III | [65] | − | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [64] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| CIRS | [67] | NR | − | NR | + | NR | NR | ? | NR |

| [66] | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| D-CASS | [37] | − | + | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| DCP | [39] | ? | − | NR | NR | NR | − | + | NR |

| [38] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [7] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [40] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [41] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [42] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| DFBC | [31] | NR | − | NR | − | NR | NR | − | NR |

| [43] | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [48] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [45] | ? | + | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [46] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [47] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [44] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| DFBC-II | [29] | NR | − | NR | ? | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [51] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [49] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [50] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [52] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| DFSC | [53] | − | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [54] | + | + | NR | ? | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| EATDM-III | [55] | - | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| DSS | [28] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | − | − | NR |

| [42] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Empowerment questionnaire | [46] | ? | + | NR | − | NR | NR | ? | NR |

| FACES IV | [69] | + | + | NR | NR | NR | + | + | NR |

| [70] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [68] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Family APGAR Index | [30] | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | NR |

| [32] | NR | + | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [73] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [74] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [72] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [71] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [15] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| FAD | [27] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | − | NR | NR |

| [75] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [76] | NR | − | NR | ? | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [16] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [77] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| F-DMSES | [56] | − | + | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | − |

| FEICS | [24] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [78] | − | + | NR | NR | NR | − | + | NR | |

| [58] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| FIAD | [93] | + | − | NR | − | NR | − | + | NR |

| [58] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| FFQ | [79] | NR | − | NR | − | NR | NR | + | NR |

| [17] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Family Functioning Style Scale | [81] | - | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [80] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| FSS-AA | [59] | − | + | NR | − | NR | − | − | NR |

| HHI-C | [60] | NR | − | NR | ? | NR | − | − | NR |

| IESS | [83] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [82] | − | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| IOCQ | [84] | + | + | NR | − | NR | NR | − | NR |

| [58] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| MDQ | [25] | + | + | NR | ? | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [61] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| MSPSS | [26] | − | + | NR | ? | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [86] | − | + | NR | NR | NR | − | + | NR | |

| [87] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [72] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [85] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [88] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| PACIC-SF | [89] | − | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | NR |

| [90] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [91] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [92] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| PSS-Fr and PSS-Fa | [22] | ? | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [93] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| PCQ | [94] | − | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [58] | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors | [23] | − | − | NR | ? | NR | − | − | NR |

| [97] | + | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [96] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [93] | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [95] | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| SPS | [21] | − | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | NR |

| [98] | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [99] | NR | − | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| S4-MAD | [62] | + | + | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| USIS | [63] | − | + | NR | ? | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soares, V.L.; Lemos, S.; Barbieri-Figueiredo, M.d.C.; Morais, M.C.S.; Sequeira, C. Diabetes Mellitus Family Assessment Instruments: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021325

Soares VL, Lemos S, Barbieri-Figueiredo MdC, Morais MCS, Sequeira C. Diabetes Mellitus Family Assessment Instruments: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021325

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoares, Vânia Lídia, Sara Lemos, Maria do Céu Barbieri-Figueiredo, Maria Carminda Soares Morais, and Carlos Sequeira. 2023. "Diabetes Mellitus Family Assessment Instruments: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021325

APA StyleSoares, V. L., Lemos, S., Barbieri-Figueiredo, M. d. C., Morais, M. C. S., & Sequeira, C. (2023). Diabetes Mellitus Family Assessment Instruments: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021325