How Does Organizational Career Management Benefit Employees? The Impact of the “Enabling” and “Energizing” Paths of Organizational Career Management on Employability and Job Burnout

Abstract

1. Introduction

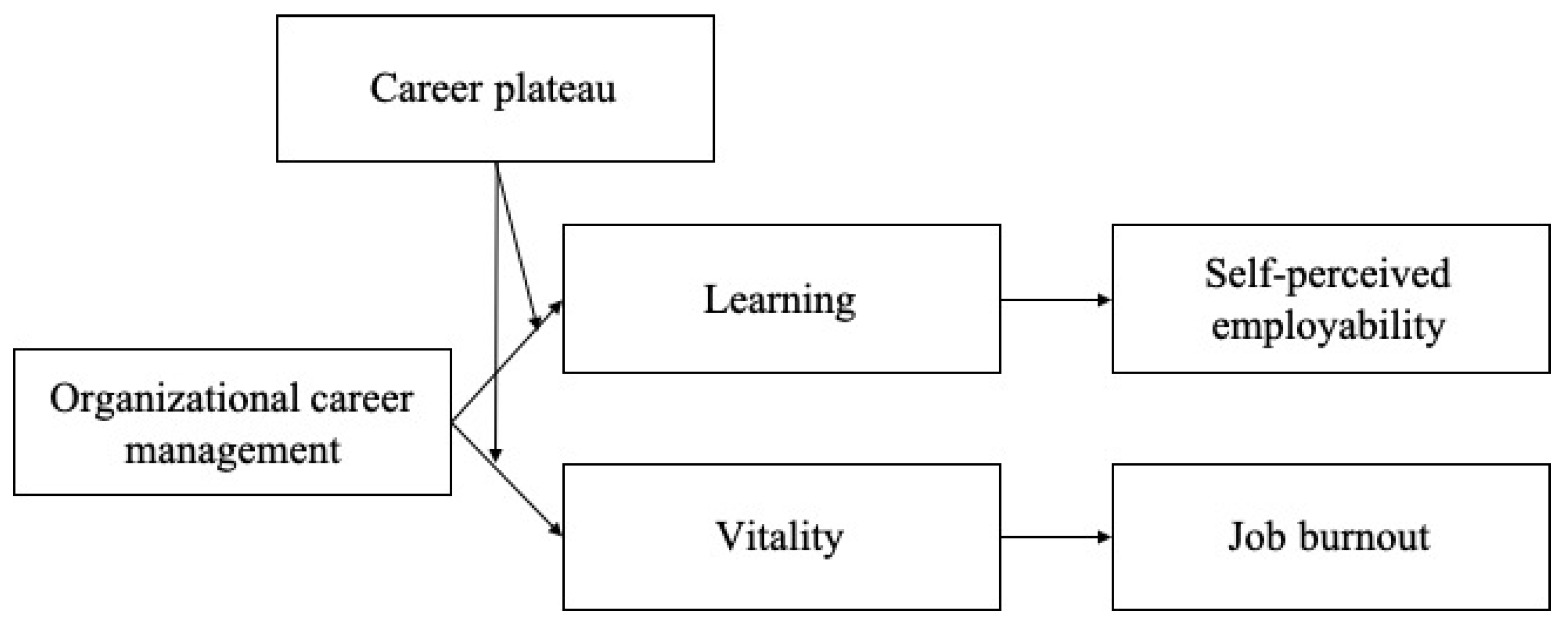

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. The “Enabling” Path

2.1.1. Organizational Career Management and Self-Perceived Employability

2.1.2. The Mediating Role of Learning

2.2. The “Energizing” Path

2.2.1. Organizational Career Management and Job Burnout

2.2.2. The Mediating Role of Vitality

2.3. The Moderating Role of Career Plateaus

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytical Strategy

3.4. Results

3.4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

3.4.2. Descriptive Results

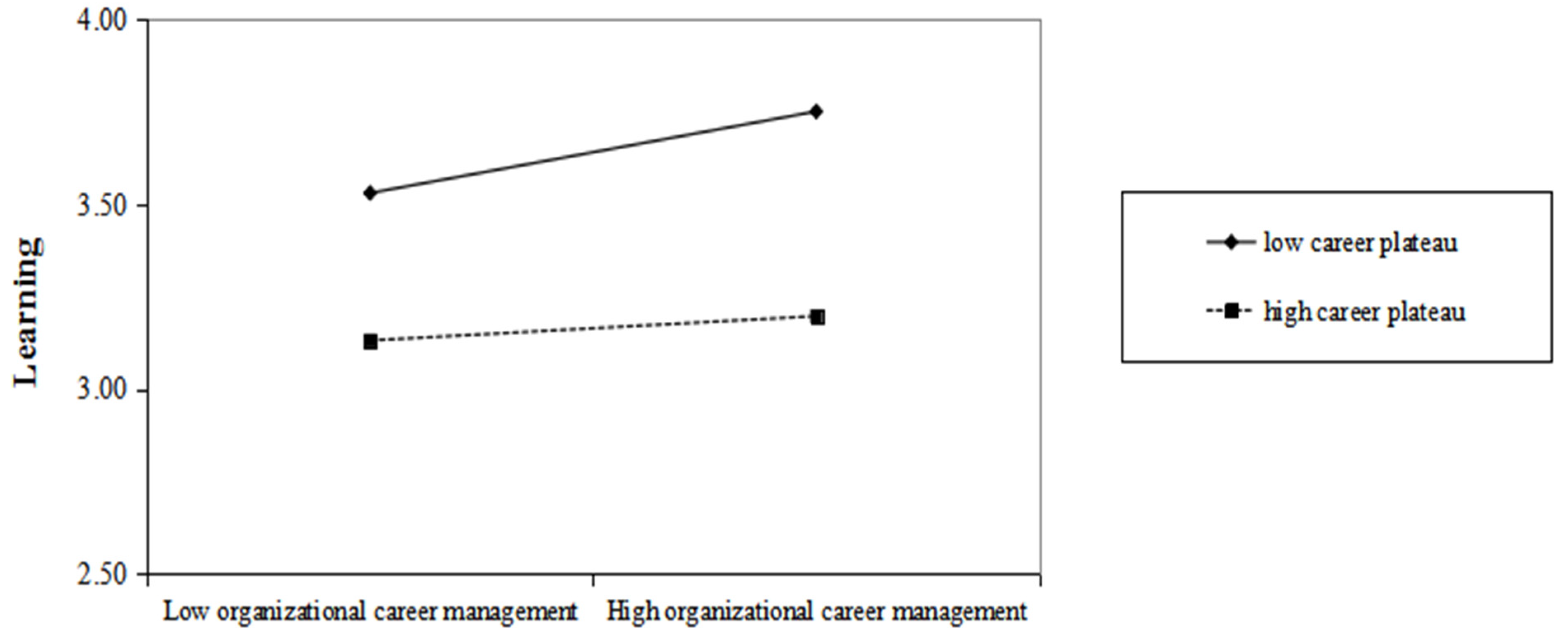

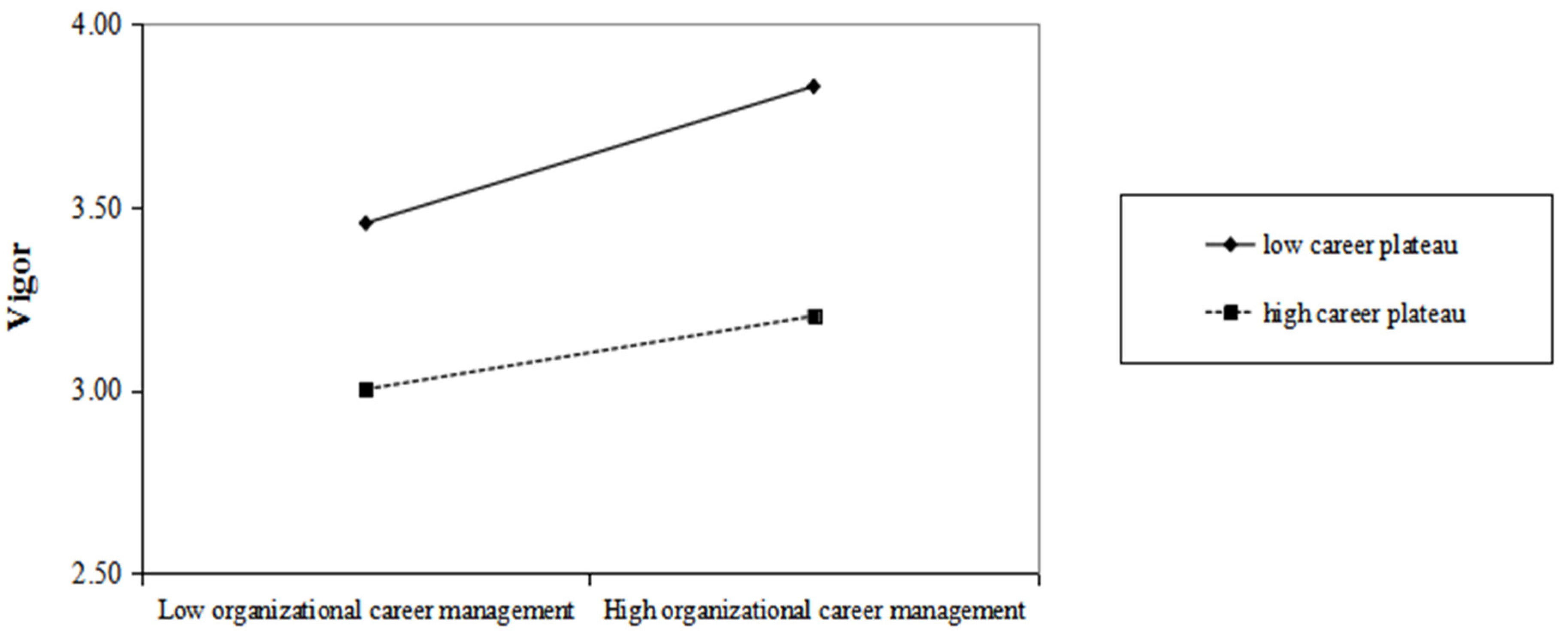

3.4.3. Hypothesis Tests

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contribution

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baruch, Y.; Peiperl, M. Career management practices: An empirical survey and implications. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 39, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Roberts, K.; Fisher, S.; Demarr, B. Career self-management: A quasi-experimental assessment of the effects of a training intervention. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 51, 935–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.X.; Mcelroy, J.C. Organizational career growth, affective occupational commitment and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Deng, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Ye, L.; Fu, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y. Career adaptability, job search self-efficacy and outcomes: A three-wave investigation among Chinese university graduates. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.R.; Fang, L.L.; Ling, W.S. Organizational career management: Measurement and its effects on employees’ behavior and feeling in China. Acta Psychol. Sinica 2002, 34, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, B.R.; Bradley, L. The impact of organizational support for career development on career satisfaction. Career Dev. Int. 2007, 12, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.B.; Guan, X.Y.; Zheng, X.M.; Hou, Z.J. Career adaptability with or without career identity: How career adaptability leads to organizational success and individual career success? J. Career Assess. 2017, 26, 717–731. [Google Scholar]

- Bagdadli, S.; Gianecchini, M. Organizational career management practices and objective career success: A systematic review and framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.J.; Zhou, W.X.; Ye, L.H.; Jiang, P.; Zhou, Y.X. Perceived organizational career management and career adaptability as predictors of success and turnover intention among Chinese employees. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 88, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutto, J. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, T.A.; Luthans, F.; Jeung, W. Thriving at work: Impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J. A dispositional approach to employability: Development of a measure and test of implications for employee reactions to organizational change. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2008, 81, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips-Wiersma, M.; Hall, D.T. Organizational career development is not dead: A case study on managing the new career during organizational change. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 28, 771–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C. Thriving at Work: Toward Its Measurement, Construct Validation, and Theoretical Refinement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ference, T.P.; Stoner, J.A.F.; Warren, E.K. Managing the career plateau. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1977, 2, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chay, Y.W.; Aryee, S.; Chew, I. Career plateauing: Reactions and moderators among managerial and professional employees. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 1995, 6, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, J.; Guest, D.; Conway, N.; Davey, K.M. A longitudinal study of the relationship between career management and organizational commitment among graduates in the first ten years at work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhercke, D.; Cuyper, N.D.; Peeters, E.; Witte, H.D. Defining perceived employability: A psychological approach. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakakis, D.; Dauth, T.; Ruigrok, W. Too much of a good thing: Does international experience variety accelerate or delay executives’ career advancement? J. World Bus. 2015, 51, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, J.; Conway, N.; Guest, D.; Liefooghe, A. Managing the career deal: The psychological contract as a framework for understanding career management, organizational commitment and work behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, A.; Herbert, I.; Rothwell, F. Self-perceived employability: Construction and initial validation of a scale for university students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntson, E.; Marklund, S. The relationship between perceived employability and subsequent health. Work Stress 2007, 21, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D.; Dutton, K.A. The thrill of victory, the complexity of defeat: Self-esteem and people’s emotional reactions to success and failure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Belschak, F.D. Work engagement and Machiavellianism in the ethical leadership process. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, C.; Sonnentag, S.; Sach, F. Thriving at Work: A Diary Study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 33, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, M.; Sels, L.; Forrier, A. Unraveling the relationship between organizational career management and the need for external career counseling. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. Proactive personality and career adaptability: The role of thriving at work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 98, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuyper, N.D.; Witte, H.D.; Kinnunen, U.; Naetti, J. The relationship between job insecurity and employability and well-being among finish temporary and permanent employees. Int. Stud. Manag. Org. 2010, 40, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalus, A.R.; Cregan, C. Cosmetic facial surgery: The influence of self-esteem on job satisfaction and burnout. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resou. 2017, 55, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, A.D.; Soens, N. Protean attitude and career success: The mediating role of self-management. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, P.; Bouwmans, M.; Vermeulen, M. Exploring teachers’ career self-management. Considering the roles of organizational career management, occupational self-efficacy, and learning goal orientation. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2019, 22, 364–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Law, K.S.; Sun, C.T.; Yang, D. Thriving of employees with disabilities: The roles of job self-efficacy, inclusion, and team-learning climate. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 58, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.G.; Long, L.R. The effects of career plateau on job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Acta Psychol. Sinica 2008, 40, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakiladevi, A.R.; Rabiyathul, S.; Basariya, S.R. Career plateau and dealing strategies. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 6, 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Flinchbaugh, C.; Luth, M.T.; Li, P. A challenge or a hindrance? understanding the effects of stressors and thriving on life satisfaction. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2015, 22, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-J.; Li, J.-M.; Wu, Y. Employees’ job insecurity perception and unsafe behaviours in human–machine collaboration. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 2409–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensemmane, S.; Ohana, M.; Stinglhamber, F. Team justice and thriving: A dynamic approach. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instrument. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, A.; Arnold, J. Self-perceived employability: Development and validation of a scale. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthen, L.K.; Muthen, B.O. Mplus [Statistical Software], 6.11; Mplus: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011.

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A. and Cambré, B. Career management in High-Performing Organizations: A Set-Theoretic Approach. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozkwitalska, M. Thriving in mono-and multicultural organizational contexts. Int. J. Contemp. Manag. 2018, 17, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M. The organizational career: Not dead but in need of redefinition. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2013, 24, 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.G.; Lu, X.; Zhou, W. Does double plateau always lead to turnover intention? Evidence from China with indigenous career plateau scale. J. Career Dev. 2015, 42, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, J.; Baird, M.; Berg, P.; Cooper, R. Flexible careers across the life course: Advancing theory, research and practice. Hum. Relat. 2018, 71, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Forgues, B.; Monties, V. The way to the top: Career patterns of Fortune 100 CEOs. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleese, C.S.; Eby, L.T.; Scharlau, E.A.; Hoffman, B.H. Hierarchical, job content, and double plateaus: A mixed-method study of stress, depression and coping responses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, E.; Allen, T.D. The role of mentoring others in the career plateauing phenomenon. Group Organ. Manag. 2009, 34, 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | SRMR | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six-factor model | 2163.97 | 1341 | 1.61 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Five-factor model | 3026.51 | 1367 | 2.21 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| Four-factor model | 3786.02 | 1371 | 2.76 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.72 |

| Three-factor model | 4386.42 | 1374 | 3.19 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.65 |

| Two-factor model | 5784.20 | 1376 | 4.20 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.51 | 0.49 |

| One-factor model | 6296.58 | 1377 | 4.57 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.50 | 0.50 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2. Age | 37.71 | 10.37 | 0.08 | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. Education | 1.89 | 0.65 | 0.11 | −0.39 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. Work years | 15.80 | 10.04 | 0.05 | 0.82 ** | −0.42 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 5. Work years in current company | 12.43 | 9.88 | 0.09 | 0.74 ** | −0.34 ** | 0.85 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 6. Organizational career management (T1) | 3.59 | 0.56 | −0.13 * | −0.12 * | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.10 | (0.94) | |||||

| 7. Career plateau (T1) | 2.69 | 0.50 | 0.21 ** | 0.09 | −0.12 * | 0.10 | 0.11 | −0.57 ** | (0.86) | ||||

| 8. Learning (T2) | 3.76 | 0.58 | −0.12 * | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.31 ** | −0.46 ** | (0.74) | |||

| 9. Vitality (T2) | 3.56 | 0.59 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.44 ** | −0.54 ** | 0.72 ** | (0.75) | ||

| 10. Self-perceived employability (T3) | 3.41 | 0.59 | −0.22 ** | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.46 ** | −0.68 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.46 ** | (0.94) | |

| 11. Job burnout(T3) | 2.56 | 0.51 | 0.04 | −0.12 * | 0.07 | −0.15 * | −0.16 ** | −0.30 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.51 ** | −0.25 ** | (0.89) |

| Predictors | Learning | Vitality | Self-Perceived Employability | Job Burnout | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 |

| Intercept | 2.16 *** | 3.40 *** | 1.56 *** | 3.37 *** | 1.71 *** | 1.01 ** | 3.79 *** | 4.56 *** |

| Gender | −0.13 * | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.20 ** | −0.17 ** | 0.02 | −0.01 |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.004 | 0.004 | 0.003 | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| Education | 0.18 ** | 0.11 * | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Work years | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.002 | −0.003 | 0.001 |

| Work years in current company | −0.01 | −0.003 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Organizational career management | 0.33 *** | 0.13 | 0.49 *** | 0.26 ** | 0.47 *** | 0.32 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.10 |

| Learning | 0.20 ** | −0.15 * | ||||||

| Vitality | 0.18 * | −0.29 *** | ||||||

| Career plateau | −0.48 *** | −0.54 *** | ||||||

| Organizational career management × Career plateau | −0.14 * | −0.16 * | ||||||

| R2 | 0.14 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.13 ** | 0.25 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, M.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.J.; Shi, H. How Does Organizational Career Management Benefit Employees? The Impact of the “Enabling” and “Energizing” Paths of Organizational Career Management on Employability and Job Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021259

Xie M, Wang G, Wu YJ, Shi H. How Does Organizational Career Management Benefit Employees? The Impact of the “Enabling” and “Energizing” Paths of Organizational Career Management on Employability and Job Burnout. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021259

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Mengying, Guorui Wang, Yenchun Jim Wu, and Haohua Shi. 2023. "How Does Organizational Career Management Benefit Employees? The Impact of the “Enabling” and “Energizing” Paths of Organizational Career Management on Employability and Job Burnout" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021259

APA StyleXie, M., Wang, G., Wu, Y. J., & Shi, H. (2023). How Does Organizational Career Management Benefit Employees? The Impact of the “Enabling” and “Energizing” Paths of Organizational Career Management on Employability and Job Burnout. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021259