Cumulative Risk and Mental Health of Left-behind Children in China: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

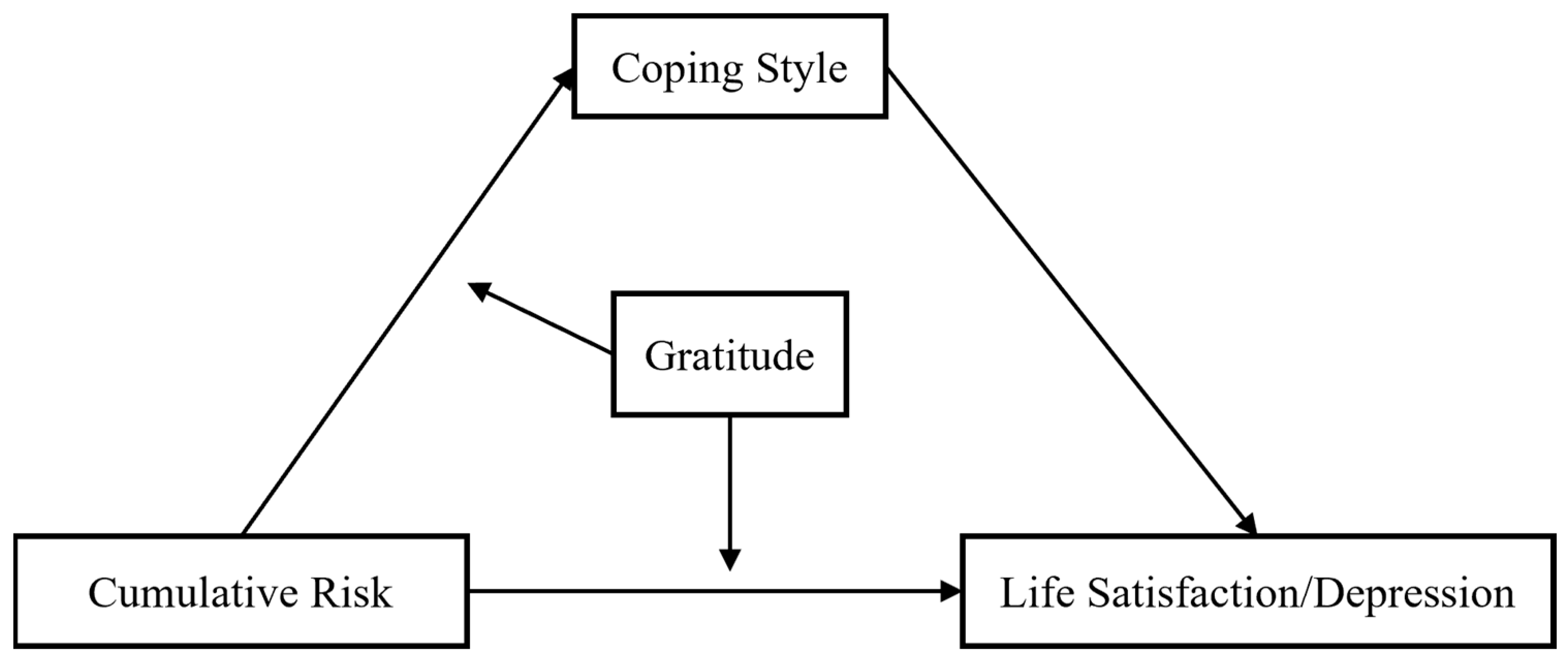

1.1. The Mediating Role of Coping Style in the Relationship between CR and Mental Health

1.2. The Moderating Role of Gratitude in the Relationship between CR and Mental Health

1.3. The Moderating Role of Gratitude in the Relationship between CR and Coping Style

1.4. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. CR

- Family risk factors.

- 2.

- School risk factors.

- 3.

- Peer risk factors.

- 4.

- Community risk factors.

2.2.2. Gratitude

2.2.3. Coping Style

2.2.4. Mental Health

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

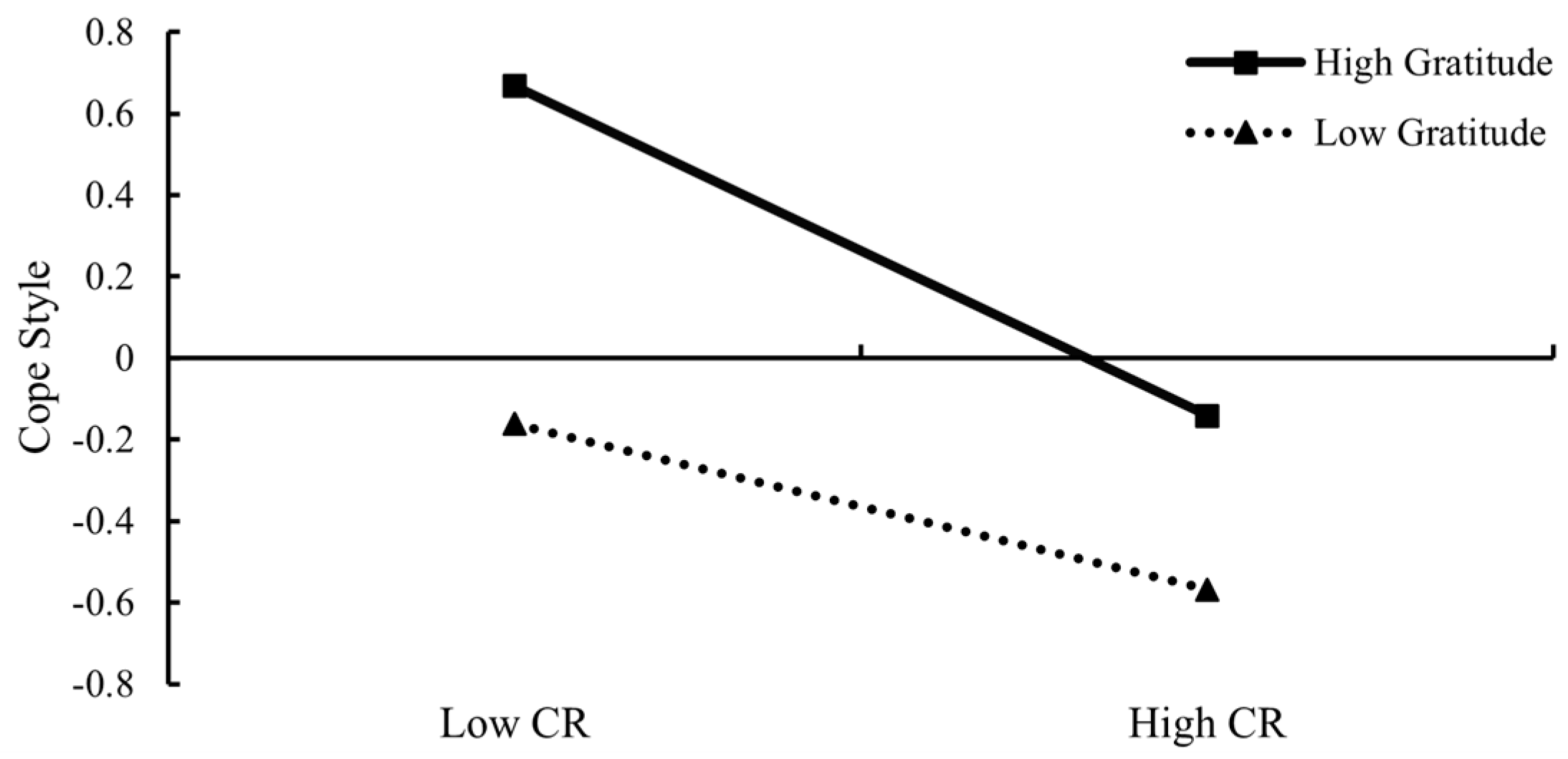

3.2. CR and Depression: A Moderated Mediation Test

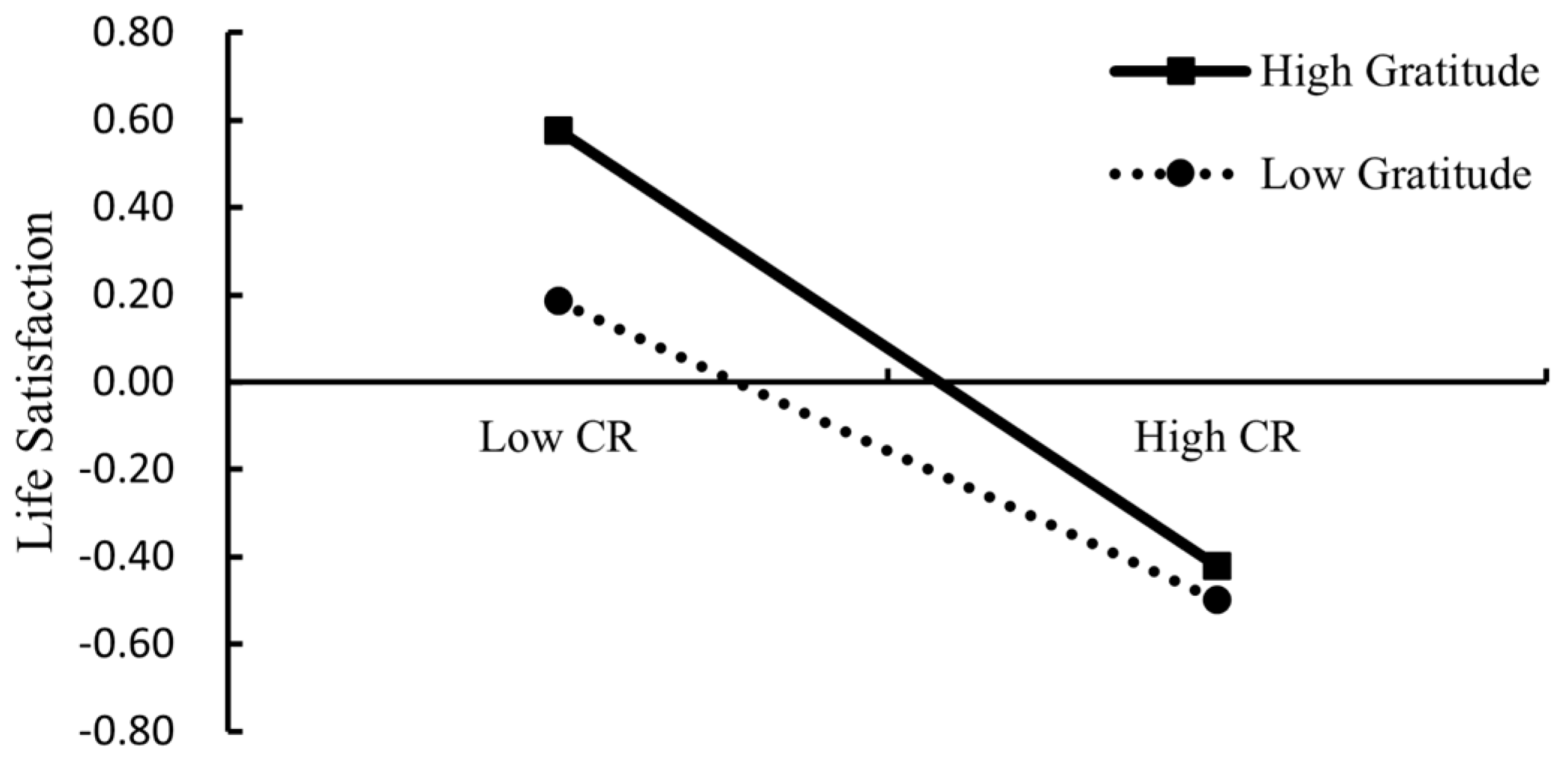

3.3. CR and Life Satisfaction: A Moderated Mediation Test

4. Discussion

4.1. The Moderated Mediation Effect of Coping Style and Gratitude in the Relationship between CR and Left-behind Children’s Depression

4.2. The Moderating Effect of Gratitude between CR and Left-behind Children’s Life Satisfaction

4.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duan, C.; Zhou, F. A Study on Children Left Behind. Popul. Res. 2005, 29, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.C.; Lv, X.L.; Jiang, Y.H.; Sun, Y.H. Left-behind children in rural China experience higher levels of anxiety and poorer living conditions. Acta Paediatr. 2014, 103, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LI, F.; Qiao, J.; He, J.; Cheng, J.; Xie, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, A.; Li, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, J. Meta analysis on the Mental Health Diagnostic Test survey results of left-behind childrens in recent ten years. Chin. J. Child Health Care 2017, 25, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, D.; Wen, Z.-f.; Zhu, X. The Difference in Mental Health between Left- behind Children and Non- left- behind Children: A Meta Analysis on SCL- 90 Questionnaire. J. Hunan First Norm. Univ. 2018, 18, 61–64+84. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology. An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenspoon, P.J.; Saklofske, D.H. Toward an Integration of Subjective Well-Being and Psychopathology. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 54, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.L.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Youth Life Satisfaction: A Review of the Literature. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 10, 583–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.C.; Liu, W.J.; Xu, Y. Change of Life Satisfaction of Chinese in Different Years of Birth. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 18, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The ecology of developmental processes. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development, 5th ed.; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Li, D.; Whipple, S.S. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 1342–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.Z.; Li, D.P.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.H.; Sun, W.Q.; Zhao, L.Y. Cumulative Ecological Risk and Adolescents’Academic and Social Competence: The Compensatory and Moderating Effects of Sense of Responsibility to Parents. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2014, 30, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W. Cumulative ecological risk and adolescent internet addiction: The mediating role of basic psychological need satisfaction and positive outcome expectancy. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2016, 48, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, J.M.; Buehler, C. Cumulative Environmental Risk and Youth Problem Behavior. J. Marriage Fam. 2004, 66, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Caldwell, C.H.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hou, Y. Cumulative risks and promotive factors for Chinese adolescent problem behaviors. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 43, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, I.; Mason, W.A.; Savolainen, J.; Chmelka, M.B.; Miettunen, J.; Jarvelin, M.R. Childhood cumulative contextual risk and depression diagnosis among young adults: The mediating roles of adolescent alcohol use and perceived social support. J. Adolesc. 2017, 60, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gach, E.J.; Ip, K.I.; Sameroff, A.J.; Olson, S.L. Early cumulative risk predicts externalizing behavior at age 10: The mediating role of adverse parenting. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Hai, M.; Su, Z.; Li, Y. Mediating effects of social problem-solving and coping efficacy on the relationship between cumulative risk and mental health in Chinese adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. An Analysis of Coping in a Middle-Aged Community Sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1980, 21, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S.; Dunkel-Schetter, C.; DeLongis, A.; Gruen, R.J. Dynamics of a Stressful Encounter: Cognitive Appraisal, Coping, and Encounter Outcomes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Dai, X. Simple coping style questionnaire. In Manual of Commonly Used Psychological Assessment Scale, Dai, X., Zhang, J., Cheng, Z., Eds.; Manual of Commonly Used Psychological Assessment Scale: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhao, M.; Jiang, H.; Hu, M. Reliability and Validity of Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire among Adolescents. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.F.; Lengua, L.J.; Garcia, C.M. Appraisal and coping as mediators of the effects of cumulative risk on preadolescent adjustment. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1416–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Emmons, R.A.; Tsang, J.A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, F.; Zhao, H. Is the individual subjective well-being of gratitude stronger? A meta-analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 1749–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Bae, S. Gratitude Moderates the Mediating Effect of Deliberate Rumination on the Relationship Between Intrusive Rumination and Post-traumatic Growth. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, N.; Qiu, S.; Alizadeh, A.; Wu, H. How Incivility and Academic Stress Influence Psychological Health Among College Students: The Moderating Role of Gratitude. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Joseph, S.; Linley, P.A. Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 26, 1076–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.Z.; Sun, Y.D.; Jiang, H.Y.; Jia, R.; Li, Z.Y. Gratitude and Problem Behaviors in Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Positive and Negative Coping Styles. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2004, 359, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; LI, D.; Zhang, W. Adolescence’s Family Finannical Difficulty and Social Adaptation: Coping efficacy of compensatory, mediation, and moderation effects. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2010, 4, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, C.M.; Maccoby, E.E.; Dornbusch, S.M. Caught between parents: Adolescents’ experience in divorced homes. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 1008–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Deng, L.; Fang, X.; Liu, C.; Lan, J. Parents-Adolescents relations and adolescent’s Internet Addiciton: The mediaiton effect of Loneliness. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2011, 27, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, B.; Xu, Y. Revision of the Short-form Egna Minnen av Barndoms Uppfostran for Chinese. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2010, 26, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z. The Characterristics of Class Environment and Its Relationship With Students’ School Adjustment in Primary and Middle School. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. Young people’s digital lives: The impact of interpersonal relationships and digital media use on adolescents’ sense of identity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2281–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Sun, X.; Niu, G.f. The Effect of Self-presentation in Online Social Networking Sites on Adolescents’Friendship Quality: The mediating Role of Positive Feedback. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2016, 32, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q. Perceived social support scale. In Rating Scales for Mental Health, 2nd ed.; Wang, X.D., Wang, X.L., Ma, H., Eds.; Chinese Mental Health Journal: Beijing, China, 1999; pp. 131–133. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J.; Hai, M.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, G. Cumulative risk and mental health in Chinese adolescents: The moderating role of psychological capital. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2020, 41, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinig, Z. The Formation Mechanism and Intervention of Gratitude Affection—From the Perspectives of Trait and Stat. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Wu, H.T.; Kong, X.N.; Wang, H. Revision of Gratitude Questionnaire-6 in Chinese adolescent and its validity and reliability. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2011, 32, 1201–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Li, N.; Ye, B. Gratitude and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: Direct, mediated, and moderated effects. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S. Initial Development of the Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1991, 12, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, D. The Change of junior middle school students’Life Satisfaction and the Prospective Effect of Resilience: A two year Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2012, 28, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, C.; Liu, L. Reliability and validity of the Youth Self-Report of Achenbach′s Behavior Checklist. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1997, 11, 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gully, S.M.; Phillips, J.M.; Castellano, W.G.; Han, K.; Kim, A. A Mediated Moderation Model of Recruiting Socially and Environmentally Responsible Job Applicants. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 935–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Guo, T.; Spruyt, K.; Liu, Z. The Role of Mindfulness in Mitigating the Detrimental Effects of Harsh Parenting among Chinese Adolescents: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model in a Three-Wave Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L. Statistical Remedies for Common Method Biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lee, Y.-T.; Chen, L. Cumulative interpersonal relationship risk and resilience models for bullying victimization and depression in adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 155, 109706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abravanel, B.T.; Sinha, R. Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between lifetime cumulative adversity and depressive symptomatology. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 61, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. Relationship between Coping Style and Mental Health: A Meta-analysis. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 22, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng-Fu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Dong-Ping, L.; Jie-Ting, X. Gratitude and Its Relationship with Well-Being. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 18, 1110–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Kee, Y.H.; Chen, L.H.; Tsai, Y.M. Relationships between being traditional and sense of gratitude among Taiwanese high school athletes. Psychol. Rep. 2008, 102, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S.; Koo, M.; Lim, N.; Suh, E.M. When Gratitude Evokes Indebtedness. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2019, 11, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turjanmaa, E.; Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. Thanks but No Thanks? Gratitude and Indebtedness Within Intergenerational Relations After Immigration. Fam. Relat. 2019, 69, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, L.; You, X. The Relation of Gratitude and Life Satisfaction: An Exploration of Multiple Mediation. J. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 40, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, S. Stressful Life Events and Life Satisfaction among Chinese Older Adults: The Role of Coping Styles. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milas, G.; Martinovic Klaric, I.; Malnar, A.; Saftic, V.; Supe-Domic, D.; Slavich, G.M. The impact of stress and coping strategies on life satisfaction in a national sample of adolescents: A structural equation modelling approach. Stress Health 2021, 37, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | M | SD | Skew | Kurt | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CR | 4.20 | 2.85 | 0.64 | −0.24 | ||||

| 2. Gratitude | 5.17 | 1.08 | −0.23 | −0.55 | −0.50 *** | |||

| 3. Cope tendency | 0.00 | 1.23 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.44 *** | 0.45 *** | ||

| 4. Life satisfaction | 3.62 | 0.86 | −0.28 | 0.28 | −0.46 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.25 *** | |

| 5. Depression | 1.42 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.37 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.28 *** |

| Predictive Variables | Outcome Variable: Cope Style | Outcome Variable: Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95%CI | β | t | 95%CI | |

| Constant | −0.71 | −1.17 | [−1.91, 0.48] | 0.48 ** | 2.71 | [0.13, 0.83] |

| Age | −0.05 | 1.15 | [−0.03, 0.12] | −0.01 | −0.69 | [−0.03, 0.01] |

| Sex | 0.12 | 1.51 | [−0.04, 0.28] | 0.06 | 2.61 | [0.02, 0.11] |

| Place of residence | −0.04 | −0.72 | [−0.16, 0.08] | −0.05 * | −2.57 | [−0.08, −0.01] |

| Number of parents Absent at home | −0.06 | −1.06 | [−0.18, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.83 | [−0.02, 0.05] |

| Time away from home | 0.03 | 0.41 | [−0.13, 0.19] | 0.01 | 0.57 | [−0.03, 0.06] |

| Type of care | 0.05 | 0.59 | [−0.12, 0.22] | −0.01 | −0.33 | [−0.06, 0.04] |

| CR | −0.13 *** | −8.05 | [−0.17, −0.10] | 0.04 *** | 7.25 | [0.03, 0.05] |

| Gratitude | 0.34 *** | 7.80 | [0.25, 0.43] | 0.01 | 0.41 | [−0.02, 0.03] |

| CR* Gratitude | −0.04 ** | −3.12 | [−0.06, −0.01] | −0.00 | −0.81 | [−0.01, 0.00] |

| Cope style | −0.06 *** | −4.96 | [−0.08, −0.03] | |||

| R2 | 0.28 | 0.18 | ||||

| F | 30.38 *** | 15.70 *** | ||||

| Predictive Variables | Outcome Variable: Cope Style | Outcome Variable: Life Satisfaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95%CI | β | t | 95%CI | |

| Constant | −0.71 | −1.17 | [−1.91, 0.48] | 3.48 *** | 7.97 | [2.62, 4.34] |

| Age | −0.05 | 1.15 | [−0.03, 0.12] | 0.04 | 1.35 | [−0.02, 0.09] |

| Sex | 0.12 | 1.51 | [−0.04, 0.28] | −0.05 | −0.79 | [−0.16, 0.07] |

| Place of residence | −0.04 | −0.72 | [−0.16, 0.08] | 0.02 | 0.47 | [−0.07, 0.11] |

| Number of parents absent at home | −0.06 | −1.06 | [−0.18, 0.05] | 0.00 | 0.06 | [−0.08, 0.09] |

| Time away from home | 0.03 | 0.41 | [−0.13, 0.19] | −0.14 * | −2.41 | [−0.25, −0.03] |

| Type of care | 0.05 | 0.59 | [−0.12, 0.22] | −0.09 | −1.45 | [−0.21, 0.03] |

| CR | −0.13 *** | −8.05 | [−0.17, −0.10] | −0.13 *** | −10.11 | [−0.15, −0.10] |

| Gratitude | 0.34 *** | 7.80 | [0.25, 0.43] | 0.09 ** | 2.64 | [0.02, 0.15] |

| CR * Gratitude | −0.04 ** | −3.12 | [−0.06, −0.01] | −0.02 * | −2.22 | [−0.04, −0.00] |

| Cope style | 0.01 | 0.47 | [−0.04, 0.07] | |||

| R2 | 0.28 | 0.24 | ||||

| F | 30.37 *** | 22.53 *** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, J.; Xie, W.; Zhang, T. Cumulative Risk and Mental Health of Left-behind Children in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021105

Xiong J, Xie W, Zhang T. Cumulative Risk and Mental Health of Left-behind Children in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021105

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Junmei, Weiwei Xie, and Tong Zhang. 2023. "Cumulative Risk and Mental Health of Left-behind Children in China: A Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021105

APA StyleXiong, J., Xie, W., & Zhang, T. (2023). Cumulative Risk and Mental Health of Left-behind Children in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021105