Clinical Stakes of Sexual Abuse in Adolescent Psychiatry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Socio-demographic data: Sex, age, socio-professional category, divorce.

- -

- Data related to SA: Nature of SA (without penetration; with penetration), number of SA (single; repeated), age of onset (<13 years; ≥13 years), relationship to the perpetrator (intrafamilial; extrafamilial), age of named perpetrator (<18 years; ≥18 years), family history of SA (yes; no), delay between the event and declaration to an adult, parental validation (yes; no). An ‘SA score’ of intensity was defined according to four SA variables considered to be ‘principal’ in the literature (nature, number, age of onset, relationship to the aggressor) with one point assigned for each item (penetration, repetition, age of onset ≤ 12 years, intrafamilial character). Once the score was measured for each patient, two sub-groups were formed: SA severity score 0 = 0, 1 or 2 points or 1 = 3 or 4 points.

- -

- Medical data: Number of suicide attempts, symptomatology, diagnosis, personal and family psychiatric history, overall level of functioning (measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning scale or GAF scale from the DSM-IV-TR).

- -

- Data related to care: Number and duration of hospitalizations.

- -

- Socio-judicial data: History of maltreatment (MT). A mistreatment score or ‘MT score’ was defined as the sum of other abuse reported by patients and/or observed by the team during hospitalization, with a point awarded for each abuse suffered (emotional abuse, physical abuse, neglect).

2.1. Statistical Analysis

2.2. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and Incidence

3.2. Description of the Study Population

3.2.1. General Description

3.2.2. Characteristics of the Sexual Abuse

- -

- Forty-nine percent of patients reported having suffered a single SA, 18% having suffered two sexual abuses, and 33% having suffered repeated sexual abuse (≥3).

- -

- The age of SA reported is between 13 and 17 years old in 46% cases, 37% between 6 and 12 years old, and 17% between 0 and 6 years old. Fourteen patients revealed that they had been sexually abused in childhood and then again in adolescence.

- -

- One or more sexual touching were reported in the majority of cases (68%), 48% of cases mentioned one or more rapes, 31% reported having been victims of other violence (pornography, exhibition, threats). Only four patients were not affected by sexual touching or rape.

- -

- The vast majority of patients reported having been abused by a male individual (98 cases), it was an adult in 61 cases, an adolescent in 37 cases, and a child in 9 cases. A woman was the named aggressor in five situations.

- -

- The named aggressor was intrafamilial in 45% of cases and extrafamilial in 55% of cases. In cases of SA in childhood (≤12 years), the named aggressor was intrafamilial in 70% of cases.

- -

- In the vast majority of situations, the young person is the one who reveals the SA (88%). At the time of disclosure, the parents validate the statements in 63% of cases (53% for intrafamilial abuse and 72% for extrafamilial abuse). The time between the onset of SA and its disclosure varies between 1 day and 9 years, and extends on average over 3 years.

- -

- At the family level (second degree) a history of SA was found in 21% of cases.

- -

- Finally, the quantification of mistreatment (via the European Child Abuse and Neglect Minimum Data Set, 2015) showed that in the majority of cases (73%), one or more other mistreatments were reported: Emotional abuse (93%), physical abuse (40%), and neglect (93%).

3.2.3. Clinical Characteristics

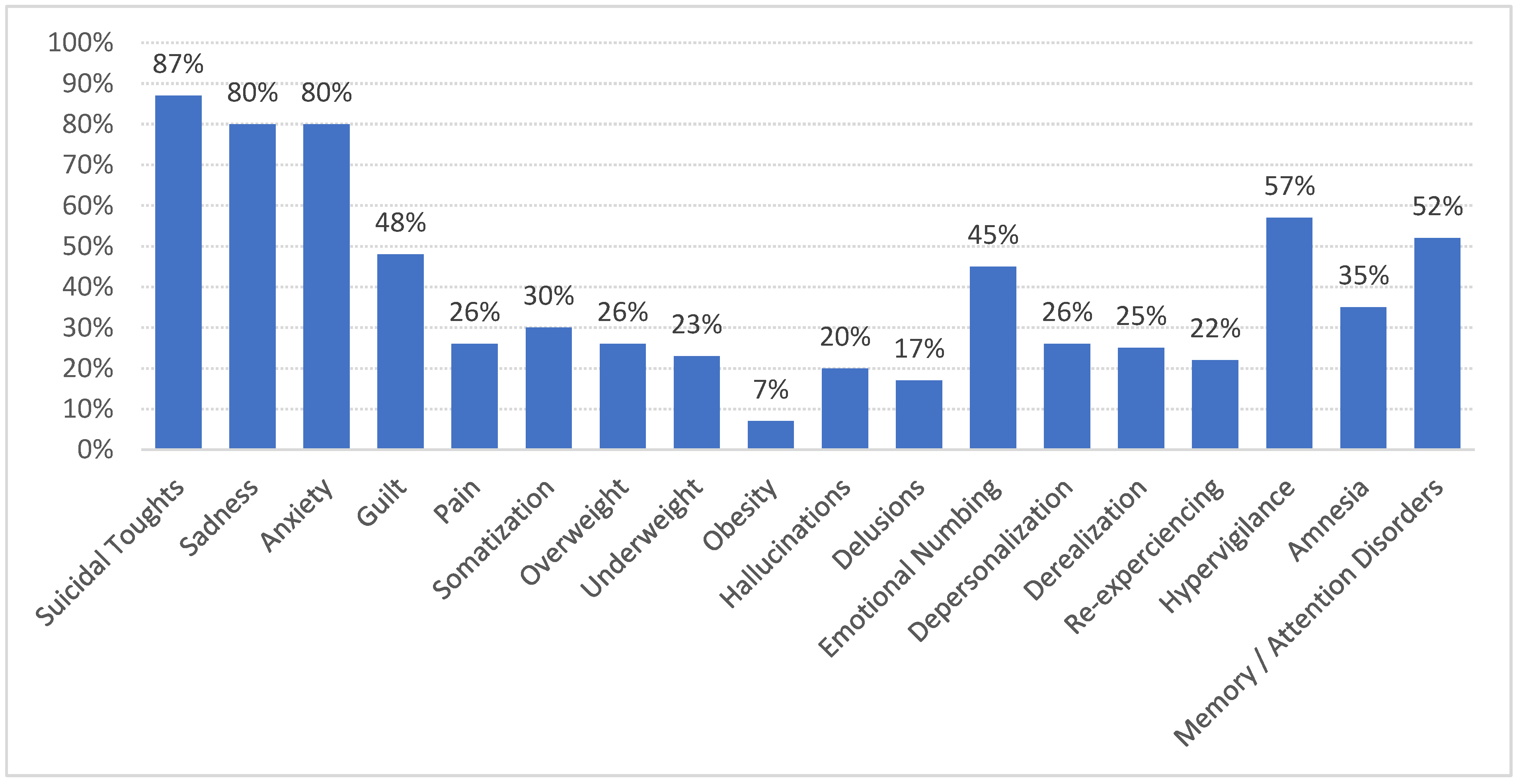

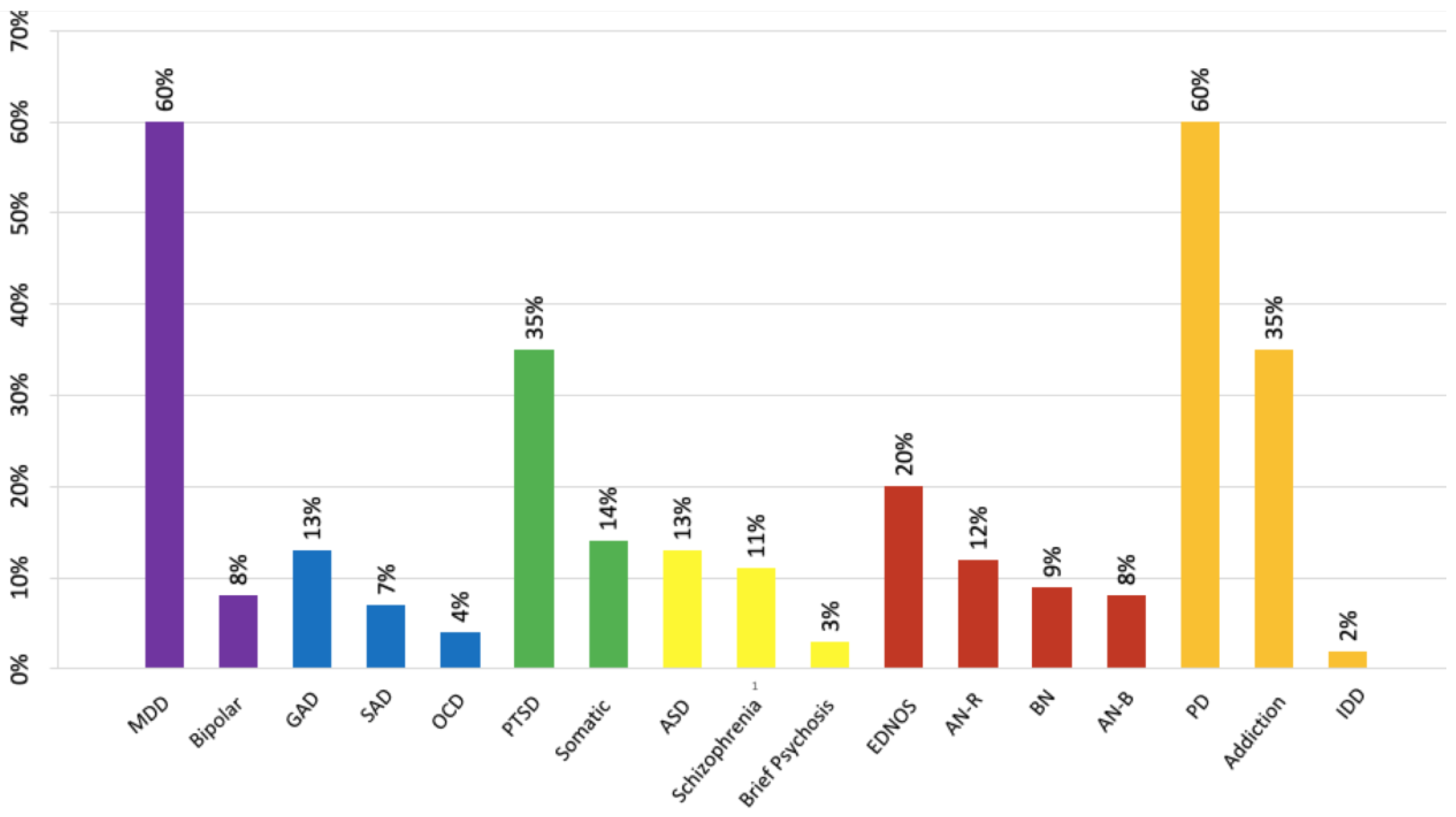

3.2.4. Symptoms and Diagnoses

3.3. Characteristics of Sexual Abuse and Medical Severity

3.4. Correlations between SA Score, MT Score, and Time to Disclosure

4. Discussion

4.1. General Features

4.2. SA Characteristics and Clinical Severity

4.3. Clinical Polymorphism

4.4. Disclosure, Parental Support

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSA | Child Sexual Abuse |

| MT | Maltreatment |

| SA | Sexual Abuse |

References

- Pereda, N.; Guilera, G.; Forns, M.; Gómez-Benito, J. The Prevalence of Child Sexual Abuse in Community and Student Samples: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, M.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Euser, E.M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. A Global Perspective on Child Sexual Abuse: Meta-Analysis of Prevalence Around the World. Child Maltreat. 2011, 16, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, J.; Bermetz, L.; Heim, E.; Trelle, S.; Tonia, T. The Current Prevalence of Child Sexual Abuse Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planty, M.; Langton, L.; Krebs, C.; Berzofsky, M.; Smiley-McDonald, H. Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994–2010: (528212013-001) 2013. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/fvsv9410.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.A.; Hamby, S.L. The Lifetime Prevalence of Child Sexual Abuse and Sexual Assault Assessed in Late Adolescence. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briere, J.N.; Elliott, D.M. Immediate and Long-Term Impacts of Child Sexual Abuse. Future Child. 1994, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, E.O.; Genuis, M.L.; Violato, C. A Meta-Analysis of the Published Research on the Effects of Child Sexual Abuse. J. Psychol. 2001, 135, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.G.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Berglund, P.A.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Childhood Adversities and Adult Psychiatric Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I: Associations with First Onset of DSM-IV Disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olafson, E. Child Sexual Abuse: Demography, Impact, and Interventions. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2011, 4, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolis, H.; Delvenne, V. Analyse quantitative des facteurs de risque familiaux chez les adolescents hospitalisés en unité de crise. Neuropsychiatr. Enfance Adolesc. 2007, 55, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailes, H.P.; Yu, R.; Danese, A.; Fazel, S. Long-Term Outcomes of Childhood Sexual Abuse: An Umbrella Review. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak-Klimek, A.; Karatzias, T.; Elliott, L.; Campbell, J.; Pugh, R.; Laybourn, P. Nature of Child Sexual Abuse and Psychopathology in Adult Survivors: Results from a Clinical Sample in Scotland: Adult Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, K.J.; McLeer, S.V.; Dixon, J.F. Sexual Abuse Characteristics Associated with Survivor Psychopathology. Child Abuse Negl. 2000, 24, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.; Dubowitz, H.; Harrington, D. Sexual Abuse: Developmental Differences in Children’s Behavior and Self-Perception. Child Abuse Negl. 1994, 18, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Beautrais, A.L.; Horwood, L.J. Vulnerability and Resiliency to Suicidal Behaviours in Young People. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, W.N.; Urquiza, A.J.; Beilke, R.L. Behavior Problems in Sexually Abused Young Children. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1986, 11, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caffaro-Rouget, A.; Lang, R.A.; van Santen, V. The Impact of Child Sexual Abuse on Victims’ Adjustment. Sex. Abuse J. Res. Treat. 1989, 2, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugaard, J.J.; Reppucci, N.D. The Sexual Abuse of Children: A Comprehensive Guide to Current Knowledge and Intervention Strategies; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McLEER, S.V.; Deblinger, E.; Atkins, M.S.; Foa, E.B.; Ralphe, D.L. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Sexually Abused Children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1988, 27, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancey, C.T.; Hansen, D.J. Relationship of Personal, Familial, and Abuse-Specific Factors with Outcome Following Childhood Sexual Abuse. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2010, 15, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaccarelli, S.; Kim, S. Resilience Criteria and Factors Associated with Resilience in Sexually Abused Girls. Child Abuse Negl. 1995, 19, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin-Vézina, D.; Daigneault, I.; Hébert, M. Lessons Learned from Child Sexual Abuse Research: Prevalence, Outcomes, and Preventive Strategies. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanarini, M.C.; Williams, A.A.; Lewis, R.E.; Reich, R.B.; Vera, S.C.; Marino, M.F.; Levin, A.; Yong, L.; Frankenburg, F.R. Reported Pathological Childhood Experiences Associated with the Development of Borderline Personality Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ystgaard, M.; Hestetun, I.; Loeb, M.; Mehlum, L. Is There a Specific Relationship between Childhood Sexual and Physical Abuse and Repeated Suicidal Behavior? Child Abuse Negl. 2004, 28, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarchev, M.; Ruijne, R.E.; Mulder, C.L.; Kamperman, A.M. Prevalence of Adult Sexual Abuse in Men with Mental Illness: Bayesian Meta-Analysis. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, E.; Moorman, J.; Ressel, M.; Lyons, J. Men with Childhood Sexual Abuse Histories: Disclosure Experiences and Links with Mental Health. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 89, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.P.; Arias, I.; Basile, K.C.; Desai, S. The Association between Childhood Physical and Sexual Victimization and Health Problems in Adulthood in a Nationally Representative Sample of Women. J. Interpers. Violence 2002, 17, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, E.-M.; Tourigny, M.; Joly, J.; Hébert, M.; Cyr, M. Les conséquences à long terme de la violence sexuelle, physique et psychologique vécue pendant l’enfance. Rev. Dépidémiol. Santé Publ. 2008, 56, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, M.; Douniol, M.; Pham-Scottez, A.; Gicquel, L.; Delvenne, V.; Nezelof, S.; Speranza, M.; Falissard, B.; Silva, J.; Corcos, M. Specific Pathways From Adverse Experiences to BPD in Adolescence: A Criteria-Based Approach of Trauma. J. Personal. Disord. 2021, 35, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Cohen, P.; Johnson, J.G.; Smailes, E.M. Childhood Abuse and Neglect: Specificity of Effects on Adolescent and Young Adult Depression and Suicidality. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999, 38, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, S.R.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Chapman, D.P.; Williamson, D.F.; Giles, W.H. Childhood Abuse, Household Dysfunction, and the Risk of Attempted Suicide Throughout the Life Span: Findings From the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA 2001, 286, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldrop, A.E.; Hanson, R.F.; Resnick, H.S.; Kilpatrick, D.G.; Naugle, A.E.; Saunders, B.E. Risk Factors for Suicidal Behavior among a National Sample of Adolescents: Implications for Prevention. J. Trauma Stress 2007, 20, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, M.H.; Samson, J.A. Childhood Maltreatment and Psychopathology: A Case for Ecophenotypic Variants as Clinically and Neurobiologically Distinct Subtypes. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 1114–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, M.; Corcos, M. Recueil Des Phénomènes de Maltraitances Chez des Adolescents Hospitalisés en Psychiatrie; ONPE: Paris, France, 2014.

- Trickett, P.K.; Noll, J.G.; Putnam, F.W. The Impact of Sexual Abuse on Female Development: Lessons from a Multigenerational, Longitudinal Research Study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2011, 23, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leserman, J.; Drossman, D.A.; Li, Z.; Toomey, T.C.; Nachman, G.; Glogau, L. Sexual and Physical Abuse History in Gastroenterology Practice: How Types of Abuse Impact Health Status. Psychosom. Med. 1996, 58, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall-Tackett, K.A.; Williams, L.M.; Finkelhor, D. Impact of Sexual Abuse on Children: A Review and Synthesis of Recent Empirical Studies. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steine, I.M.; Nielsen, B.; Porter, P.A.; Krystal, J.H.; Winje, D.; Grønli, J.; Milde, A.M.; Bjorvatn, B.; Nordhus, I.H.; Pallesen, S. Predictors and Correlates of Lifetime and Persistent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Suicide Attempts among Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1815282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniglio, R. The Impact of Child Sexual Abuse on Health: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Raby, K.L.; Labella, M.H.; Roisman, G.I. Childhood Abuse and Neglect, Attachment States of Mind, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2017, 19, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.S.; Sher, L. Child Sexual Abuse and the Pathophysiology of Suicide in Adolescents and Adults. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2013, 25, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, B.J.; Clara, I.P.; Enns, M.W. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and the Structure of Common Mental Disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2002, 15, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kira, I.A.; Shuwiekh, H.; Kucharska, J. Screening for Psychopathology Using the Three Factors Model of the Structure of Psychopathology: A Modified Form of GAIN Short Screener. Psychology 2017, 08, 2410–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milot, T. Trauma Complexe: Comprendre, Évaluer et Intervenir; D’enfance; Presses de l’Université du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2018; ISBN 978-2-7605-4982-1. [Google Scholar]

- Collin-Vézina, D.; De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M.; Palmer, A.M.; Milne, L. A Preliminary Mapping of Individual, Relational, and Social Factors That Impede Disclosure of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2015, 43, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyr, M.; Hébert, M.; Tourigny, M. (Eds.) L’agression Sexuelle Envers les Enfants; Collection Santé et société; Presses de l’Université du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2011; ISBN 978-2-7605-3012-6. [Google Scholar]

- Yurteri, N.; Erdoğan, A.; Büken, B.; Yektaş, Ç.; Çelik, M.S. Factors Affecting Disclosure Time of Sexual Abuse in Children and Adolescents. Pediatr. Int. 2022, 64, e14881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hébert, M.; Tremblay, C.; Parent, N.; Daignault, I.V.; Piché, C. Correlates of Behavioral Outcomes in Sexually Abused Children. J. Fam. Violence 2006, 21, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElvaney, R.; McDonnell Murray, R.; Dunne, S. Siblings’ Perspectives of the Impact of Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure on Sibling and Family Relationships. Fam. Process 2022, 61, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, E.; Wilson, C.; McElvaney, R. Childhood Sexual Abuse: Sibling Perspectives. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP3304–NP3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.E.; Bruce, C.; Wilson, S. Children’s Disclosure of Sexual Abuse: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research Exploring Barriers and Facilitators. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2018, 27, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolen, R.M.; Lamb, J.L. Parental Support and Outcome in Sexually Abused Children. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2007, 16, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Salem, S.; Bras, N.; Renaudet-Calvo, C. Le silence autour des victimes d’inceste. Soins 2021, 66, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baril, K.; Tourigny, M.; Hébert, M.; Cyr, M. Agression Sexuelle: Victimes (Mineurs). In Questions de Sexualité au Québec; Liber: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2008; pp. 18–26. [Google Scholar]

| GAF Score | Number of Hospitalizations | Number of Suicide Attempts | Time to Disclosure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the victim | ||||

| ≥13 years (n = 46%) | 34.2 (±7.43) | 2.88 (±1.86) | 1.79 (±2.20) | 1.08 (±1.64) |

| <13 years (n = 54%) | 31.6 (±8.61) | 3.18 (±2.02) | 1.58 (±1.47) | 4.45 (±3.36) |

| p = 0.11 | p = 0.46 | p = 0.61 | p < 0.001 | |

| Number of SA | ||||

| Single (n = 49%) | 34.1 (±7.4) | 2.70 (±1.83) | 1.35 (±1.75) | 2.16 (±2.89) |

| Recurrent (n = 51%) | 31.9 (±8.48) | 3.38 (±1.90) | 2.28 (±2.0) | 4.02 (±3.16) |

| p = 0.2 | p = 0.05 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | |

| Nature of SA | ||||

| Without penetration (n = 52%) | 32.8 (±8.32) | 3.12 (±1.98) | 1.83 (±2.30) | 2.96 (±3.17) |

| With penetration (n = 48%) | 32.2 (±8.21) | 3.04 (±2.0) | 1.70 (±1.82) | 3.22 (±3.29) |

| p = 0.71 | p = 0.86 | p = 0.77 | p = 0.73 | |

| Relationship to the perpetrator | ||||

| Extrafamilial (n = 55%) | 33.6 (±7.99) | 2.6 (±1.6) | 1.56 (±2.10) | 1.70 (±2.46) |

| Intrafamilial (n = 45%) | 31.3 (±8.43) | 3.53 (±2.26) | 1.95 (±1.91) | 4.24 (±3.40) |

| p = 0.18 | p = 0.025 | p = 0.34 | p < 0.001 | |

| Age of the named perpetrator | ||||

| <18 years (n = 43%) | 36.1 (±7.14) | 2.42 (±1.3) | 1.36 (±1.34) | 2.95 (±3.17) |

| ≥18 years (n = 57%) | 30.6 (±8.23) | 3.31 (±2.2) | 1.97 (±2.29) | 3.17 (±3.47) |

| p < 0.01 | p = 0.016 | p = 0.11 | p = 0.7 | |

| Parental validation | ||||

| Yes (n = 63%) | 33.2 (±7.85) | 2.92 (±2.07) | 1.90 (±2.31) | 2.37 (±2.81) |

| No (n = 37%) | 32.3 (±8.96) | 3.37 (±1.8) | 1.59 (±1.37) | 4.22 (±3.52) |

| p = 0.74 | p = 0.11 | p = 1 | p = 0.037 | |

| Family history of SA | ||||

| No (n = 79%) | 33.3 (±8.0) | 2.83 (±1.91) | 1.48 (±1.71) | 2.96 (±3.18) |

| Yes (n = 21%) | 31.8 (±5.11) | 2.5 (±1.2) | 1.89 (±2.40) | 2.01 (±2.25) |

| p = 0.3 | p = 0.86 | p = 0.6 | p = 0.37 |

| Coefficients | p | Global p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA score | 1 vs. 0 | 2.13 [0.760; 3.34] | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MT score | 1 vs. 0 | 0.285 [−1.09; 1.74] | 0.78 | <0.01 |

| 2 vs. 0 | 0.776 [−0.543; 2.10] | 0.28 | - | |

| 3 vs. 0 | 2.42 [0.944; 3.90] | <0.01 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robin, M.; Schupak, T.; Bonnardel, L.; Polge, C.; Couture, M.-B.; Bellone, L.; Shadili, G.; Essadek, A.; Corcos, M. Clinical Stakes of Sexual Abuse in Adolescent Psychiatry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021071

Robin M, Schupak T, Bonnardel L, Polge C, Couture M-B, Bellone L, Shadili G, Essadek A, Corcos M. Clinical Stakes of Sexual Abuse in Adolescent Psychiatry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021071

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobin, Marion, Thomas Schupak, Lucile Bonnardel, Corinne Polge, Marie-Bernard Couture, Laura Bellone, Gérard Shadili, Aziz Essadek, and Maurice Corcos. 2023. "Clinical Stakes of Sexual Abuse in Adolescent Psychiatry" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021071

APA StyleRobin, M., Schupak, T., Bonnardel, L., Polge, C., Couture, M.-B., Bellone, L., Shadili, G., Essadek, A., & Corcos, M. (2023). Clinical Stakes of Sexual Abuse in Adolescent Psychiatry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021071